SCIENCE SALON # 85

Michael Shermer with Deepak Chopra — Metahuman: Unleashing Your Infinite Potential

In this conversation long-time adversaries and now friends Michael Shermer and Deepak Chopra make an attempt at mutual understanding through the careful unpacking of what Deepak means when he talks about the subject-object split, the impermanence of the self, nondualism, the mind-body problem, the nature of consciousness, and the nature of reality. Shermer also pushes Deepak to translate these deep philosophical, metaphysical, and psychological concepts into actionable take-home ideas that can be put to use to reduce human suffering and help people lead lives that are more meaningful and purposeful.

In the book Deepak includes a survey called Nondual Embodiment Thematic Inventory (NETI), final scores of which range from 20 to 100, on “how people rank themselves on qualities long considered spiritual, psychological, or moral.” Shermer scored a 62, which Chopra said is “not bad”. Take the test yourself in the book or Google it online to read more about it.

Listen to the podcast via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, iHeartRadio, and TuneIn.

Check Us Out On YouTube.

Science Salons • Michael Shermer

Skeptic Presents • All Videos

You play a vital part in our commitment to promote science and reason. If you enjoy the Science Salon Podcast, please show your support by making a donation.

In the following retrospective on the occasion of the recent death of Napoleon Chagnon, one of the world’s most famous and controversial anthropologists, we reprint Dr. Michael Shermer’s analysis of the charges leveled against Dr. Chagnon by the journalist Patrick Tierney in his book Darkness in El Dorado (originally published in Skeptic magazine 9.1 in 2001), which at the time caused a huge media stir. Not only was Chagnon vindicated by multiple inquiries, his view of human nature was solid at the time and has held up ever since. Welcome to the Anthropology Wars over the nature of human nature…

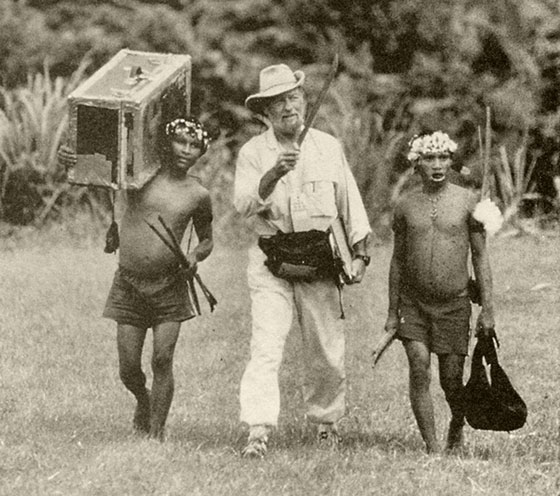

Figure 1 (above): The man behind the controversy: anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon accompanies two Yąnomamö men on a 1995 field study. From Darkness in El Dorado, 2000.

Spin-Doctoring the Yąnomamö

Science as a Candle in the Darkness of the Anthropology Wars

There is a maxim anthropologists often cite about the geopolitics of diplomacy and warfare among indigenous peoples: The enemy of my enemy is my friend. In reality, of course, the maxim applies to virtually all groups, from tribes and villages to city-states and nation-states — recall the temporary friendship between the US and USSR from 1941-1945 that promptly dissolved into the Cold War upon the defeat of their common enemy.

I thought of this maxim on Monday, November 20, 2000, when I interviewed journalist Patrick Tierney for the science edition of NPR affiliate KPCC’s Airtalk, when he was in Los Angeles on tour for his just published book Darkness in El Dorado: How Scientists and Journalists Devastated the Amazon.1 Tierney had just flown down from San Francisco where, the previous day, he was pummeled by a panel of experts in front of a thousand scientists gathered at the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association.

Among the many scientists that Tierney goes after none take more hits than the anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon, whose study of the Yąnomamö people of Amazonia is arguably the most famous ethnography since Margaret Mead’s Samoan classics. Since I knew of Chagnon’s reputation as an intellectual pugilist who has accumulated a score of enemies over the decades, I fully expected that, in obedience to the maxim, they would have rallied around Tierney in a provisional alliance. With a couple of minor exceptions, however, there was almost universal condemnation of the book. A British science writer told Skeptic Senior Editor Frank Miele, who was in attendance: “If I had taken such a beating as Tierney I would have crawled out of the room and cut my throat.”2

Tierney did seem shell-shocked, as he timorously tiptoed into the studio with a subdued countenance. On the air he seemed almost apologetic for his book, emphasizing that he was not presenting the final word on the subject of the mistreatment of the Yąnomamö but, rather, he was merely suggesting the need to investigate the scandalous charges against Chagnon and others that he had gathered in his decade of research.

A wispy thin man with an edge of wilderness about him, left over from a waif-like nomadic lifestyle spent chasing down what he thought might be (and his publisher trumpeted as) the anthropological scandal of all time, Tierney struck me as a conciliatory man ill-suited for the fight he had instigated. Indeed, he seemed the very embodiment of the type of man Rush Limbaugh would call a bleedingheart, tree-hugging liberal, and someone environmentalists would call a friend. His publicist at W.W. Norton told me that he was flat broke from years of grant-less, salary-less research and that his very survival hinged on the success of this book. Her interpretation of the AAA meeting, which she attended in hopes of this being a coming out celebration for a potentially bestselling book, was that Tierney had few friends there because he was an outsider, a mere journalist at play in the field of the scientists.3 Who was he to stick his nose in the private business of professionals whose union card — the Ph.D. — was hard earned through the centuries-long system of mentorship and hoop-jumping, not unlike the rites of passage young men endure in many indigenous cultures? Had Tierney simply not paid his scientific dues, or was there something else going on that turned Chagnon’s erstwhile enemies into new found friends? […]