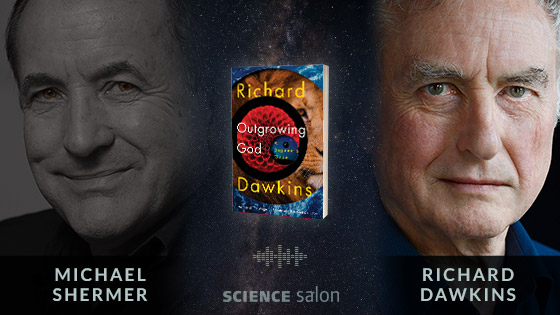

SCIENCE SALON # 89

Michael Shermer with Richard Dawkins — Outgrowing God: A Beginner’s Guide

In 12 fiercely funny, mind-expanding chapters, Richard Dawkins explains how the natural world arose without a designer — the improbability and beauty of the “bottom-up programming” that engineers an embryo or a flock of starlings — and challenges head-on some of the most basic assumptions made by the world’s religions.

In this wide-ranging conversation Shermer and Dawkins discuss:

- how Outgrowing God encapsulates his life’s work in two broad areas: (1) science, reason, and evolution theory; (2) God, Religion, and Faith. A “Dawkins 101” book and a perfect gift to friends and family.

- his commitment to the truth, as best explained by science.

- Is the Bible a “Good Book”?

- Is adhering to a religion necessary, or even likely, to make people good to one another?

- why religion is over-determined

- separating religion from God beliefs

- Is religion and belief in God an evolutionary adaptation or a byproduct (or both)?

- Why we don’t need God in order to be good

- How do we decide what is good?

- human nature: selfish/selfless, violent/peaceful, better angels/inner demons

- breaching the Is-Ought barrier

- the future of atheism

- career advice for young scientists and scholars

- getting courage from science

- the multiverse: “You Cannot be Serious!”

Richard Dawkins is a fellow of the Royal Society and was the inaugural holder of the Simonyi Chair for the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. He is the acclaimed author of many books, including The Selfish Gene, The God Delusion, The Magic of Reality, Climbing Mount Improbable, Unweaving the Rainbow, The Ancestor’s Tale, The Greatest Show on Earth, and Science in the Soul. He is the recipient of numerous honors and awards, including the Royal Society of Literature Award, the Michael Faraday Prize of the Royal Society, the Kistler Prize, the Shakespeare Prize, the Lewis Thomas Prize for Writing about Science, the Galaxy British Book Awards Author of the Year Award, and the International Cosmos Prize of Japan.

Listen to the podcast via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, iHeartRadio, and TuneIn.

Check Us Out On YouTube.

Science Salons • Michael Shermer

Skeptic Presents • All Videos

You play a vital part in our commitment to promote science and reason. If you enjoy the Science Salon Podcast, please show your support by making a donation.

Is the statement “We are living in a post-truth world” true? If your answer is “yes” then the answer is “no” because you’ve just evaluated the statement in an evidentiary manner, so evidence still matters and facts still matter. Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker explains why were are not living in a post-truth world in this deeply insightful cover story from Skeptic magazine 24.3 (2019). This article is based on the keynote address1 delivered to the annual conference of the Heterodox Academy in June of 2019. (Photo above by Jeremy Danger)

About the image above: A danger of repressing open debate is that it sets off equal and opposite backlashes. The regressive left is an incubator of the alt-right.

Why We Are Not Living in a Post‑Truth Era

An (Unnecessary) Defense of Reason and a (Necessary) Defense of Universities’ Role in Advancing it

Anyone who urges universities to live up to their mission of promoting knowledge, truth, and reason is bound to be confronted with the objection that these aspirations are just so 20th century. Aren’t we living in a post-truth era? Haven’t cognitive psychologists shown that humans are fundamentally irrational? Mustn’t we acknowledge that the pursuit of disinterested reason and objective truth are Enlightenment anachronisms?

The answer to all of these questions is “no.”

First, we are not living in a post-truth era. Why not? Consider the statement “We are living in a post-truth era.” Is it true? If so, it cannot be true.

Likewise, it is not the case that humans are irrational. Consider the statement, “Humans are irrational.” Is that statement rational? If it is, it cannot be true—at least, if it is uttered and understood by humans. (It would be another thing if it was an observation exchanged among an advanced race of space aliens.) If humans were truly irrational, who specified the benchmark of rationality against which humans don’t measure up? How did they conduct the comparison? Why should we believe them? Indeed, how could we understand them?

In his book The Last Word, the philosopher Thomas Nagel showed that truth, objectivity, and reason are not negotiable.2 As soon as you start making a case against them, you are making a case, which means you are implicitly committed to reason. Nagel calls this argument Cartesian, after Descartes’ famous argument that just as the very fact that one is pondering one’s existence shows that one must exist, the very fact that one is examining the validity of reason shows that one is committed to reason. A corollary is that we don’t defend or justify or believe in reason, and we certainly do not, as it is sometimes claimed, have faith in reason. As Nagel puts it, each of these is “one thought too many.” We don’t believe in reason; we use reason.

This may sound like logic-chopping, but it’s built into the way we make everyday arguments. As long as you’re not bribing or threatening your listeners to mouth agreement with you, but trying to persuade them that you’re right—that they should believe you, that you’re not lying, or full of crap— then you have conceded the primacy of reason. As soon as you try to argue that we should believe things by any route other than reason, you’ve lost the argument, because you’ve appealed to reason. That is why a defense of reason is unnecessary, perhaps even impossible.

As for the “post-truth era,” journalists should retire this cliché unless they can keep up a tone of scathing irony. It comes from the observation that some politicians—one in particular—lies a lot. But politicians have always lied. They say that in war, truth is the first casualty, and that can be true of political war as well. (The expression “credibility gap” had its heyday during the administration of Lyndon Johnson in the 1960s.) And the bending or inverting of truth by people in power has long been consequential, leading, for example, to the Spanish-American war, the First World War, the Vietnam War, and the Iraq War, right up to the near miss in the Persian Gulf in 2019.

Another inspiration for the post-truth cliché is the recent prominence of “fake news.” But this, too, is not a new development. The title of the James Cortada and William Aspray’s forthcoming Fake News Nation: The Long History of Lies and Misinterpretations in America, is self-explanatory, though the long history is by no means confined to America.3 The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the hoaxed proceedings of a secret meeting of Jews plotting global domination, was advanced as fact by a number of prominent people in subsequent decades, including the industrialist Henry Ford. Countless pogroms, lynchings, and deadly ethnic riots have been sparked by rumors of the alleged perfidy of some minority group. […]