I’ve been thinking about sex lately, and so have you. Well, only in an appropriately skeptical way, of course. It has always fascinated me, as a social scientist, that for an activity allegedly so “natural”—a simple biological activity like eating, singing, or walking—that sex is so complicated. If it’s a “normal” part of life, let alone “simple,” why do people throng therapists’ offices and buy nine zillion books to answer their question, “Am I normal?” Yes, you are, buddy, and also no, you aren’t. Compared to whom, when, and where?

A few years ago I wrote an essay for this column on the manufacture of “female sexual dysfunction” and, forgive me, the cockamamie statistics being used to justify it. I know that readers have been panting ever since for a followup on the pursuit by Big Pharma to find a libido-boosting drug for women. Finding such a drug is the Holy Grail of Modern Medications, and if you can get FDA approval, that adds three or four mini-miracles, all in one little pill. Thanks to tireless activism by skeptical, scientifically-minded sexologists and researchers, organized by Leonore Tiefer and the New View Campaign, “Challenging the Medicalization of Sex,” the first such drug, Procter & Gamble’s Intrinsa (a testosterone patch), failed in 2004 to get FDA approval because it didn’t work and wasn’t safe.

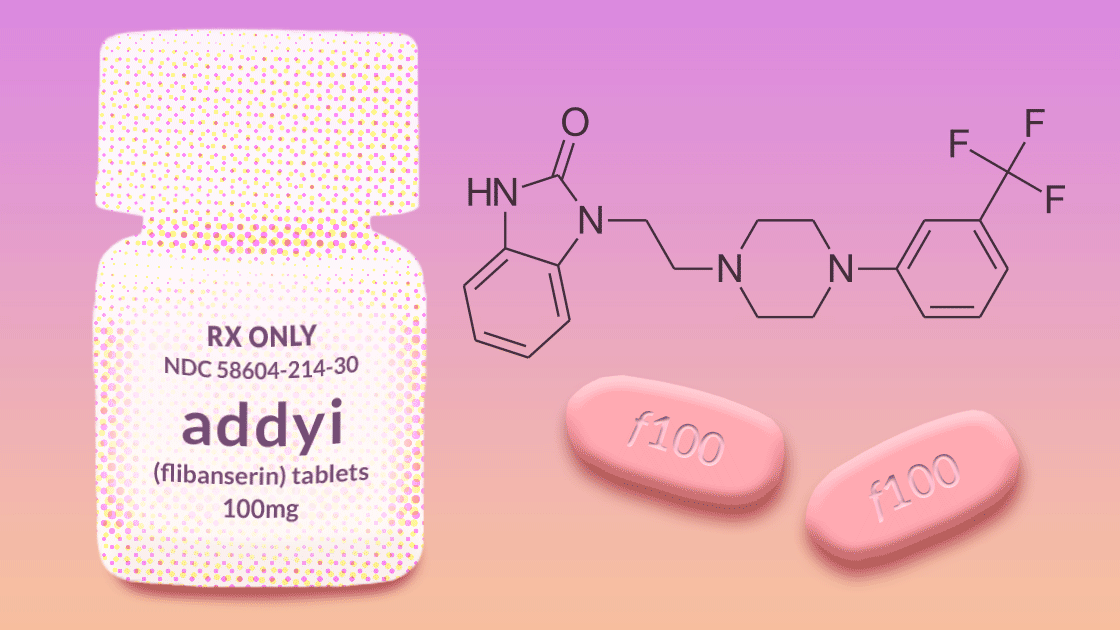

Procter & Gamble’s failure begat Boehringer Ingelheim’s efforts to get approval for flibanserin (now known as Addyi) in 2009. The FDA’s advisers voted unanimously against the drug because it increases “substantial somnolence and dangerous interactions with alcohol and other drugs” compared with placebo. And oh yes, by the way, it “failed to improve sexual desire measured with a daily electronic diary.”

Boehringer’s failure begat Sprout pharmaceuticals, which bought the rights to flibanserin and resubmitted it for FDA approval in 2013, only to have it rejected yet again. The FDA again concluded that treatment differences between women on the drug and those on a placebo were trivial and that any possible benefits did not “clearly outweigh safety concerns.”

Sprout’s failure begat renewed determination, and the company resubmitted flibanserin to the FDA in 2015. This time the FDA approved the drug—even though there was no new evidence of the drug’s benefits or safety. Within two days, Valeant Pharmaceuticals had bought flibanserin for one billion dollars.1 According to a 2018 meta-analysis, women taking flibanserin “experienced 0.5 more satisfying sexual encounters a month and scored 0.3 points higher on a 5-point sexual desire scale.”2

I’m not making this up.

Once again, the mere fact that empirical research doesn’t give you the answer you want doesn’t deter you from persisting, especially with one billion dollars at hand. Accordingly, in 2019, the FDA approved a new formulation, bremelanotide (Vyleesi), a drug that a woman must inject into her abdomen or thigh an hour or so before sex (now that’s fun foreplay for you), in spite of its adverse side effects, the most common of which are nausea (40%), facial flushing (20%), and headache (11%). Four in ten women who take this drug feel nauseous? That’s an erotic high for you. “Although the trials met statistical significance for change in sexual desire elements and distress related to sexual desire, the clinical benefit may only be modest,” said one review.3 Actually, women scored slightly higher on desire but did not have more satisfying sexual experiences. “Modest” benefits, I have learned, usually means “fuhgeddaboudit.”

Here’s the punch line in that review: at least flibanserin “led to an average of only one additional sexual experience every two months.” Bremelanotide…to none. Both can cause serious harm. “A politicized industry-sponsored advocacy campaign and conflicted patient and expert testimony likely influenced flibanserin’s approval at its third attempt. Bremelanotide, with even weaker efficacy, capitalized on the regulatory precedent set by the approval of flibanserin.”4

Note those words: regulatory precedent. If you can get your ineffective drug over the low bar of approval, you have set a precedent. And how then can the FDA not approve your next ineffective drug without withdrawing approval for the former one? There was no public advisory committee hearing for bremelanotide, apparently because once the FDA had approved Addyi by the slimmest of margins, on the scarcest of evidence, every other new drug for “female sexual dysfunction” would have to get a pass as well.

The mindless reliance on precedent, even when a drug is shown to be ineffective and potentially harmful, should be a wakeup call for skeptical awareness, because it is so easy to rely on precedent for decisions, practices, and beliefs rather than have to re-interrogate them at regular intervals. But wait, wasn’t this drug approved some years ago? It must be fine now.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 27.2

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

The irony is that there actually is a medication that improves sexual functioning for women in menopause and beyond: estrogen.5 Approximately 80 percent of midlife women suffer from menopausal symptoms for an average of 7.4 years, including loss of sexual desire and vaginal atrophy, which causes pain during intercourse. Women were scared off estrogen in 2002 because of the Women’s Health Initiative’s claims that it causes breast cancer, dementia, stroke and “all-cause mortality,” but, without headlines or fanfare, the WHI has since walked back virtually every one of those scare stories.6 Now they say that estrogen is the best and safest treatment for menopausal symptoms, from hot flashes to vaginal pain, and the FDA has approved its use.7 And by the way, it increases longevity by three to four years.

What a challenge for skeptics: being wary of ineffective drugs that are hyped by Big Pharma, without reflexively rejecting medications that are effective. To be sure, when it comes to sex, the most difficult challenge is to stop Americans from worrying that they aren’t normal and that they shouldn’t have to take anything less than 100 percent sexual satisfaction lying down. Although lying down might be a good place to start. ![]()

References

- Agarwal, R., & Baid, R. (2018). Flibanserin: A controversial drug for female hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 27(1), 154–157. https://doi.org/10.4103/ipj.ipj_20_16

- Jaspers, L., Feys, F., Bramer, W., Franco, O., Leusink, P., & Laan, E. (2016). Efficacy and Safety of Flibanserin for the Treatment of Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder in Women. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(4), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.8565

- Mayer, D., & Lynch, S. (2020). Bremelanotide: New Drug Approved for Treating Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 54(7), 684–690. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028019899152

- Mintzes, B., Tiefer, L., & Cosgrove, L. (2021). Bremelanotide and flibanserin for low sexual desire in women: the fallacy of regulatory precedent. Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin, 59(12), 185–188. https://doi.org/10.1136/dtb.2021.000020 1.

- Pines, A. (2010). Guidelines and recommendations on hormone therapy in the Menopause. Journal of Mid-Life Health, 1(1), 41–42. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-7800.66990

- Bluming, A., & Tavris, C. (2018). Estrogen Matters. Little, Brown Spark.

- Flores, V. A., Pal, L., & Manson, J. A. E. (2021). Hormone therapy in menopause: Concepts, controversies, and approach to treatment. Endocrine Reviews, 42(6), 720–752. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnab011

About the Author

Carol Tavris, PhD, is a social psychologist and writer. She has written hundreds of articles, book reviews, and op-eds on many topics in psychological science. Her books include Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me), with Elliot Aronson; Estrogen Matters; and The Mismeasure of Woman. A Fellow of the Association for Psychological Science, she has received numerous awards for her efforts to promote science and skepticism, including an award from the Center for Inquiry’s Independent Investigations Group; an honorary doctorate from Simmons College for her work in promoting critical thinking and gender equity; and the Bertrand Russell Distinguished Scholar, Foundation for Critical Thinking, Sonoma State.

This article was published on August 16, 2022.