Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey is one of the most significant megalithic sites in the world and perhaps the greatest archaeological enigma ever discovered. Archaeologists had once thought construction of megalithic monuments was far beyond the capabilities of hunter-gatherers. They believed that people had to invent farming prior to settling in communities. Only with sufficient food resources could people settle down and develop the social hierarchy required to construct megalithic architecture. Göbekli Tepe helped to turn such thoughts upside down.

That’s what archaeologists think anyway. Alternative archaeologists (sometimes labeled by archaeologists as pseudoarchaeologists), by contrast, see Göbekli Tepe as proof that a mysterious lost civilization or ancient aliens were responsible for its construction. They believe that combined with alleged evidence of an older Sphinx and other monuments around the world, orthodox archaeologists will finally be forced to concede they have been misled about the antiquity of humanity.

Dating to at least 12,000 years ago, Göbekli Tepe is by far the oldest and one of the largest megalithic structures on Earth. That alone makes it one of the most important archaeological sites ever discovered. It was first described by Peter Benedict as part of a joint project between the Universities of Istanbul and Chicago (1963–1972).1 Based on the lack of water it was determined it could not have been a permanent settlement. In 1995 the German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt, in conjunction with the German Archaeological Institute, began the first scientific study of Göbekli Tepe. When Schmidt started excavating, he was stunned, not by the famous T-pillars that he had already seen at Nevali Çori (27 miles away), but by the unprecedented scale of what could best be described as a megalithic mountain sanctuary. Göbekli Tepe was not built in a day. Evidence indicates the site was used for thousands of years.

For archaeologists this seemed almost impossible. The necessary planning and coordination challenged the traditional theories about the capabilities of wandering bands of hunter-gatherers. By definition they did not possess sufficient resources or social hierarchy to construct anything like Göbekli Tepe. Clearly their civilization was more complex than anyone had previously thought.

Enclosures

The scale of Göbekli Tepe is enormous. It is about 1,000 feet wide, with a maximum height of 50 feet above the plateau (Figure 1). There are multiple adjacent stone enclosures where each could crudely be described as a Turkish Stonehenge. However, the Stonehenge analogy fails to convey the majesty and significance of the site. Enclosure diameters vary from 30–100 feet and each enclosure contains two monolithic T-shaped pillars of up to 18 feet tall. It is estimated that the largest pillar weighs over 50 tons. Closer inspection reveals some of the center T-pillars are stylized human bodies with arms and hands, but no faces. The limestone pillars were quarried not far from the site. All this from only a small fraction of the site that has been excavated. There is likely much more to come.

The central T-pillars are more precarious than they appear. Today, if not for carefully placed supports, many of the pillars would topple. Some archaeologists believe each enclosure was originally covered with a roof. The roof would support the central pillars, while offering protection from the elements. For some enclosures the entrance was likely through an opening in the roof.

Many of the T-pillars are covered with depictions of animals and a few with people. Snakes are the most common, followed by foxes, and then vultures. The principle animal depicted varies from enclosure to enclosure. Snakes dominate in enclosure A, foxes in enclosure B, boars in C, and mostly birds in D.2 Most human depictions are of decapitated heads or headless bodies. Where discernable, animal and human depictions are of males. The one human exception is likely graffiti that was added later. Some of the human bodies have erect penises.

The two central T-pillars are enclosed by a stone wall that contains several smaller T-pillars. The number of wall pillars varies from enclosure to enclosure. Benches line the interior of the enclosure walls. To date there is no evidence of domestic use — there are no fireplaces, ovens, or other traces of domestic life. Instead, it appears that Göbekli Tepe was used for ritual or communal functions — a regional social gathering site for meetings and feasts. Some believe Göbekli Tepe itself was associated with funeral rituals. Archaeological evidence indicates the tools were contemporaneous with hunter-gatherer technology. There is no evidence of farming or domestication — only wild plant and animal species have been found.3

Building something as complex as Göbekli Tepe would require a huge investment in time and resources. To excavate, transport, carve, and erect such pillars required detailed planning. Depending on the number of individuals involved, it has been estimated it would take days to several weeks to complete a single enclosure.4 The mystery is how could they possibly have built it. The labor force alone probably outnumbered the members of a single band of hunter-gatherers. The basic problem is food. Acquiring enough food to feed such a large group of people for that long was considered an almost impossible task for hunter-gatherers.

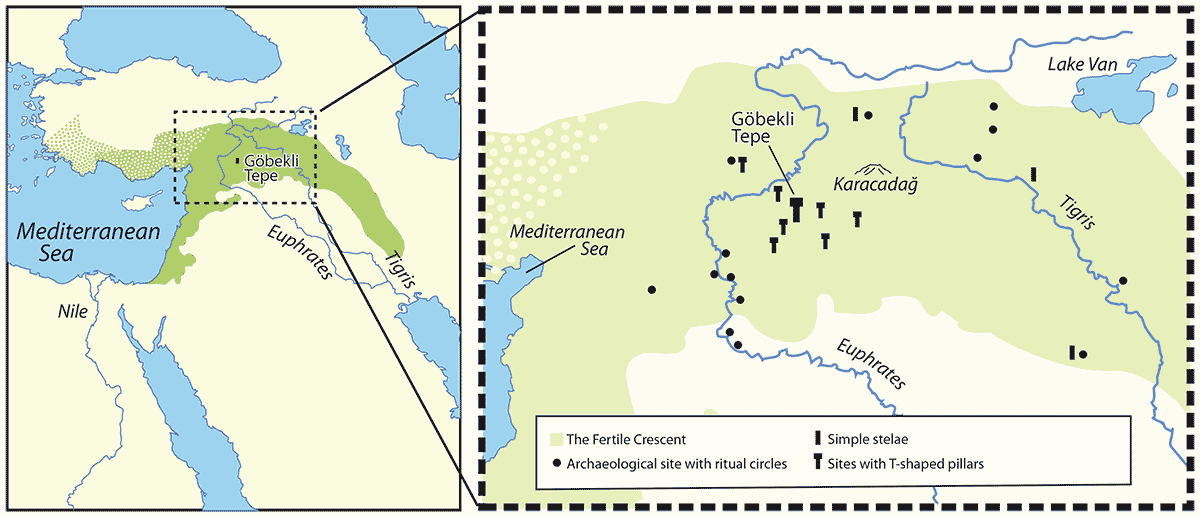

Figure 2: The Fertile Crescent ca. 7500 BCE, with current distribution of sites with T-shaped pillars, and with simple limestone stelae. Modified after Schmidt 2006: Copyright DAI.

Göbekli Tepe does not exist in isolation (Figure 2). As noted, similar T-pillars have been unearthed at Nevali Çori. Additional T-pillars have been identified at Karahan Tepe, Harbetsuvan Tepe, Sefer Tepe, and Hamzan Tepe. At Karahan Tepe at least 266 T-pillars have been identified. We know very little about these sites as they have not yet been excavated.5 However, recently excavation work has begun at Karahan Tepe and Harbetsuvan Tepe.

Intentional Burial?

Göbekli is Turkish for “potbelly” and refers to the profile of the hill that resembles a human navel cavity on a pot belly. To a trained eye, even from a distance, Göbekli Tepe is instantly recognizable as an artificial hill. A “tepe” in Turkish or a “tell” in English is an artificial hill, one of the most famous being the ancient city of Jericho. Tepes like Jericho form by the slow accumulation of debris of human settlement in the same spot over hundreds of years. They contain an archaeological treasure trove of human occupation.

But the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe were not buried by the slow accumulation of human debris as at Jericho. Instead they were deliberately buried (although in some instances, individual enclosures may have been buried by some catastrophic event). That the enclosures would be buried appears to have been part of the plan from the beginning. In some cases, prior to burial, sculptures, tools, or other objects were set at the base of the T-pillars. It is not known how long each enclosure was used prior to burial or why the enclosures were buried. It has been suggested that each T-pillar represented a specific community leader or perhaps a group.6, 7

The fill material consists of fist to head sized limestone rubble, bone fragments (animal and human), and pieces of flint tools. Many of the bones, mostly gazelle, wild cattle, and other wild animals depicted on the T-pillars, were cracked open to eat the marrow. The sheer volume of bones indicates feasting on a massive scale.8

Skull Cult?

The fill material includes some human bone fragments. Based on appearance, the human bones were treated in a similar fashion to the animal bones. They were smashed into small pieces and some contain cut marks.9 Numerous fragments of human skulls have been found in the fill material. Some of these fragments display processing marks associated with defleshing. The sharpness of the cut marks indicates the bones were modified at an early stage of decay. Postmortem skull modifications appear to be part of their burial ritual. Sections of three human skulls have been found. A drill hole at the top of one of the skulls suggests it was hung on a rope.10 It is thought that the skulls might represent ancestor worship, or perhaps trophy displays of dispatched enemies.

The obsession with human skulls at this time is well documented, so it is not surprising to find that Göbekli Tepe could be part of the widespread Neolithic Skull Cult. Decapitation was not restricted to human bodies. In some cases, human statues were carved, then intentionally decapitated and the heads were placed next to the central T-pillars prior to burying the enclosure.

Downsizing

For whatever reason, instead of progressively increasing in scale and complexity, the enclosures shrank over time. The largest exposed enclosures (30–100 feet wide) date to the 12th millennium BP, while the smaller rectangular enclosures (10 × 13 feet) date to the 11th millennium BP. The height of the central T-pillars shrinks from 18 feet to 6.5 feet.11 In some of the small enclosures the ring of wall T-pillars is absent. In other cases, even the two central T-pillars are missing. Ground penetrating radar has identified additional enclosures of various sizes and shapes. Some appear to be significantly larger than anything currently excavated.2 Following the downsizing trend these larger enclosures are likely older.2

The oldest carbon-14 date indicates the filling of the enclosures began by 11,700–11,300 BP.12 This dates the filling of the enclosure, not the original construction date. Additional carbon-14 dates obtained from wall plaster indicates the last time the walls were repaired, not when the enclosure was first built. What archaeologists have uncovered thus far is only a fraction of the site, up to 90 percent remains buried. As most of Göbekli Tepe remains buried, no one can say yet how old it is. Schmidt believes the earliest as yet unexcavated structures at Göbekli Tepe could be as much as 14,000–15,000 years old.13 If he is correct, this would make the earliest building at Göbekli Tepe up to 9,000 years older than Stonehenge and 10,000 years older than the Pyramids of Giza. Carbon-14 dating indicates that by 10,000 BP Göbekli Tepe was abandoned.2

Rock the Cradle

Göbekli Tepe is located within the Fertile Crescent, which is known as the Cradle of Civilization. If you could rewind time you would see Earth experience a series of short dramatic climatic swings from 14,700–11,700 BP as the ice age came to an end. The first was an abrupt warming event known as the Bølling-Allerød interstadial. The climate in Turkey during the Bølling-Allerød would have provided favorable conditions for hunter-gatherers.12, 14, 15, 16 Comparable to today’s climate, wild grains and animal herds would have carpeted the ground — easy pickings for huntergatherers. Hunter-gatherer settlements from this time have been discovered in Syria and elsewhere. It is likely that undiscovered settlements dating from this time also exist in southeastern Turkey.17

The warming was followed by a cooling event at 12,900 BP called the Younger Dryas, marking an abrupt return to ice-age conditions. In Turkey, the climate turned cold and dry. Wild grains retreated to areas of moist soil, making grain gathering and hunting more problematic.18 Still, it appears the Syrian settlements established during the Bølling-Allerød were continuously occupied throughout the Younger Dryas.18, 19

What instigated the Younger Dryas is debatable. The best hypothesis is that it was caused by a release of a huge volume of glacial meltwater that temporarily shut down the Atlantic meridional circulation. The cold spell lasted for 1,200 years. When the climate warmed again around 11,700 BP, it marked the end of the Ice Age. This was the start of a long period of climatic stability known as the Holocene interstadial — the geological epoch we live in.

Wild Times at Göbekli Tepe

As temperatures rose at the start of the Holocene wild grains again carpeted the land, including in the Göbekli Tepe area. Massive herds of grazing animals quickly followed. This was a land of plenty and ideal conditions for hunting and gathering. Given the abundance of wild grains and game there would be no reason to start farming.

For at least 200,000 years people lived as hunter-gatherers, foraging for whatever daily food they could find. A successful hunt could supply enough meat to feed the group for several days. What little technology there was had to be carried from place to place.

Perhaps the largest single step in our history was the change from forager to farmer. The established view was that rapid warming at the end of the Ice Age produced favorable conditions for farming. Farming was considered the first necessary step towards permanent settlement. It freed people from daily chores of survival. Unburdened by the necessity of devoting their lives to gathering food, farming came with a bonus, something never seen before, a huge food surplus. The surplus food gave farmers the freedom to develop complex religious rituals and monumental architecture. Some members of the population would be set free to create a workforce capable of constructing something like Göbekli Tepe. Except, of course, Göbekli Tepe wasn’t built by farmers.

Long before Göbekli Tepe was discovered, archaeologists already knew that farming began in the Fertile Crescent. DNA fingerprinting indicates that wheat was first domesticated near the Karacadağ mountains in Southern Turkey. The oldest evidence of wheat domestication and farming at 10,400 BP comes from Nevali Çori.20, 21 Although exactly where plant domestication began remains an area of debate amongst archaeologists.

Much of the Göbekli Tepe region is covered by vast stands of grass, including wild wheat and barley. In 1967 Jack Harlan conducted an experiment to see how much wild grain he could gather using a flint bladed sickle. He concluded that a Karacadağ family group, working for just three weeks, could easily gather more grain than they could possibly consume in a year. More important is that excess grain could easily be stored and traded with other less sedentary tribes.22 The natural abundance of both wild grains and animals created ideal conditions for the huntergatherers. In short, they did not farm because they did not need to. Known as affluent foragers, they relied solely on wild species of plants and animals. The natural abundance of food resources provided the freedom to develop complex religious rituals and monumental architecture.

Evidence from Syria indicates gathering of wild wheat dates to 30,000 BP.23 By 23,000 BP wild grains formed into bread were used as a source of food.24 From as long ago as 30,000 years our ancestors relied on the same grains that they would eventually domesticate. By the time they switched to farming they already had the technology to process the grains.

Archaeologists already knew that hunter-gatherer groups congregated at specific locations and times for ritual purposes. Göbekli Tepe appears to be part of that tradition. These gatherings played an essential role in the exchange of information, goods, and marriage partners. They also strengthened bonds between huntergatherer communities. Ritual activities included feasting on a massive scale, as is evident by the huge volume of animal bones discovered at Göbekli Tepe. Feasting also probably involved the consumption of large amounts of alcohol. At Göbekli Tepe there is some evidence that beer was brewed. The construction of Göbekli Tepe itself would have been part of the community building process. Such gatherings typically occurred at predominant locations. Göbekli Tepe itself is a dominant landmark constructed on a predominant limestone plateau visible for miles.

Does it Have to be a Lost Civilization?

Much of the fascination with Göbekli Tepe by alternative archaeologists is the fact that there is still so much we do not know about it, and where mystery pervades a scientific subject, pseudoscience often jumps in. Much of alternative archaeology about Göbekli Tepe involves what triggered the Younger Dryas. I mentioned the most popular hypothesis above, but another is that the destruction and abrupt cooling were the result of a comet impact. Unfortunately, the comet left little, if any clear evidence. Seemingly against all odds, a second comet hit in 11,600 BP, destroying Atlantis. Like the previous impact it left little if any evidence. Only this time the comet produced an abrupt global warming event.

In this alternative history, simultaneous to the second impact some of the lucky survivors made it to Göbekli Tepe in 11,600 BP. There they bestowed the dual technological gifts of megalithic architecture and farming. The problem is that if Klaus Schmidt’s dating is correct, they had already been constructing megalithic structures at Göbekli Tepe for a thousand years or more. Farming would have been very much a white elephant gift given the abundance of wild grain. Since the actual work was performed by the indigenous people, farming would have been a make-work project if there ever was one.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 25.2

According to the most prominent of alternative archaeologists, Graham Hancock, “No, the problem at Göbekli Tepe is the pristine, sudden appearance, like Athena springing full-grown and fully armed from the brow of Zeus, of what appears to be an already seasoned civilization so accomplished that it “invents” both agriculture and monumental architecture at the apparent moment of its birth.”25 Here Hancock seems to have lost sight of the mystery of Göbekli Tepe — the construction of megalithic architecture without any evidence of agriculture.

To make his interpretation work, Hancock takes the liberty of assigning Göbekli Tepe (15,000–10,000 BP), agriculture (10,400 BP), the start of the Younger Dryas (12,900 BP), the end of the Younger Dryas (11,700 BP), and the construction of the Sphinx (4,500 BP) all to the same time as the destruction of the imagined civilization (12,900 BP) and the flooding of Atlantis (11,600 BP). The survivors transferred the technology with the goal of restarting their civilization at Göbekli Tepe. Unfortunately, according to Hancock “it didn’t quite work.”26 That is quite an understatement, as the quality and scale of the megalithic architecture declined until eventually the site was abandoned. The supposed technology transfer marks the beginning of the enclosure burials. There is no evidence the gift of farming was ever used. Instead of invigorating Göbekli Tepe the technological gifts appear to lead to its decline and eventual collapse.

Meanwhile in Egypt other survivors, working with aliens, used acoustic levitation and other advanced technologies to create the Sphinx and the Hall of Records beneath. Perhaps at Göbekli Tepe, if they had applied the full array of their technological capabilities or at least brought more practical gifts, things might have turned out better.

Writing a New Chapter

The people of Göbekli Tepe, with sufficient natural resources, found the time to write a new chapter in the history of life. Archaeologists have read only a small part of that story. Still, they have read enough to know that they were wrong about farming being a prerequisite for megalithic architecture, and they admit it. In some ways they are actually happy to be wrong, as it proves the scientific method works — they were just following the evidence. The evidence against the farming-first paradigm had been building for a while; it was Göbekli Tepe that put the final nail in that coffin. The ability to construct something like Göbekli Tepe is fundamentally controlled by the availability of food. It makes no difference if the food is planted or simply gathered. Affluent hunter-gatherers were gathering wild grains long before Göbekli Tepe was built. We now know gathering provided more than sufficient food resources. Freed from the demands of daily foraging, the people of Göbekli Tepe derived the benefits of farming without all the work. Klaus Schmidt said it best:

The results of these recent and ongoing excavations have not turned our picture of world history upside down, but they are adding a splendid and colourful new chapter between the period of the hunters and gatherers of the Ice Age and the new world of the food producing cultures of the Neolithic period the extent of which had not been predicted some years ago — a chapter which is enlarged year by year by the ongoing excavations at PPN sites in the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia.

About the Author

Robert Adam Schneiker has been studying the Sphinx for more than seven years. He has a M.S. in geology/geophysics. He designed and developed SEVIEW, the industry standard contaminant modeling software. Regulatory agencies use his modeling software to develop soil contaminant concentrations protective of groundwater quality. He conducts transport and fate modeling training seminars across America. He has presented papers on contaminant transport and fate modeling in the United States, the European Union and Canada. Trained as a petroleum geophysicist his project experience includes: riskbased evaluations, vadose zone and groundwater modeling, remedial investigations, geophysical exploration and groundwater resources exploration. Mr. Schneiker is an avid bicyclist who also enjoys kayaking, hiking and off-road fourwheeling.

The author would like to thank Jens Notroff and David S. Anderson for taking the time to comment on an earlier draft version of this article.

References

- Benedict, P. 1980. “Survey Work in Southeastern Anatolia.“ R.J. Braidwood Çambel. (Ed.) In Guneydogu Anadolu Tarihoncesi Arastirmalari / Prehistoric Research in Southeastern Anatolia, 151–191.

- Dietrich, O. and Notroff, J. A. 2015. “Sanctuary, or so Fair A House? In Defense of an Archaeology of Cult at Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe.” N. Laneri. (Ed.) In Defining the Sacred: Approaches to the Archaeology of Religion in the Near East, 75–89.

- Schmidt, K. 2000. “Göbekli Tepe, Southeastern Turkey: A Preliminary Report on the 1995–1999 Excavations.“ Paléorient, Vol. 26, 1, 45–54.

- Notroff, J. 2019. “The Importance of Göbekli Tepe.“ The NonSequitur Show. April 4.

- Moetz, F.K. and Çelik, B. 2012. “T-Shaped Pillar Sites in the Landscape around Urfa.“ R. and J. Curtis Matthews. (Eds.) In Proceeding of the 7th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient East, 695–703.

- Clare, L. 2019. “Unknowns About Göbeklitepe.“ Arkeofili. January 28.

- Notroff, J. 2020. Personal communication. January 26.

- Dietrich, O., et al. 2012. “The Role of Cult Feasting In the Emergence of Neolithic Communities. New Evidence from Göbekli Tepe, South-eastern Turkey.“ Antiquity, Vol. 86, 674–695.

- Schmidt, K. 2011. “Göbekli Tepe: The stone age sanctuaries. New results of ongoing excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs.“ Documenta Praehistorica, Vol. 37, 239–256.

- Gresky, J., Haelm, J. and Clare, L. 2017. “Modified human crania from Göbekli Tepe provide evidence for a new form of Neolithic skull cult.“ Science Advances, Vols. 3, e1700564.

- Notroff, J., et al. 2015. “What modern lifestyles owe to Neolithic feasts: The early mountain sanctuary at Göbekli Tepe and the onset of food-production.“ Actual Archeology, Vol. 15, 32–49.

- Dietrich, O. 2011. “Radiocarbon dating the first temples of mankind. Comments on 14CDates from Göbekli Tepe.“ Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie, 4, 12–25.

- Conrad, T. 2012. Cradle of the Gods. Atlantic Productions; National Geographic.

- Roberts, N., et al. 2001. “The tempo of Holocene climatic change in the eastern Mediterranean region: new high-resolution crater-lake sediment data from central Turkey.“ Holocene, 11, 721–736.

- Wick, L., Lemcke, G. and Sturm, M. 2003. “Evidence of Lateglacial and Holocene climatic change and human impact in eastern Anatolia: high-resolution pollen, charcoal, isotopic and geochemical records from the laminated sediments of Lake Van, Turkey.“ Holocene, 13, 665–675.

- Jones, M.D, Roberts, C. N. and Leng, M. J. 2007. “Quantifying climatic change through the last glacial-interglacial transition based on Lake Isotope palaeohydrology from central Turkey.“ Quat Res, 67, 463–473.

- Haldorsen, S., et al. 2011. “The climate of the Younger Dryas as a boundary for einkorn domestication.“ Veget Hist Archaeobot. 20, 305–318.

- Hillman, G., et al. 2001. “New evidence of Lateglacial cereal cultivation at Abu Hureyra on the Euphrates.“ Holocene, 11, 383–393.

- Willcox, G, Buxo, R. and Herveux, L. 2009. “Late Pleistocene and early Holocene climate and the beginning of cultivation in northern Syria.“ Holocene. 19, 151–158.

- Balter, M. 2007. “Seeking Agriculture’s Ancient Roots.“ Science, Vol. 316, 1830–1835.

- Nesbitt, M. 2002. “When and where did domesticated cereals first occur in southwest Asia, In The Dawn of Farming in the Near East. Studies in Near Eastern Production.” R.T. J. Cappers and S. Bottema (Eds.). Subsistence and Environment, Vol. 6, 113–132.

- Harlan, J.R. 1967. A wild wheat harvest in Turkey. Archaeology, 20, 197–201.

- Allaby, R.G., et al. 2017. “Geographic mosaics and changing rates of cereal domestication.“ Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372: 20160429.

- Piperno, D.R., et al. 2004. “Processing of wild cereal grains in the Upper Palaeolithic revealed by starch grain analysis.” Nature, 430, 670–673.

- Hancock, G.B. 2015. Magicians of the Gods: The Forgotten Wisdom of Earth’s Lost Civilization. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Hancock, G.B. 2016. “The Mystery of Göbekli Tepe.“ London Real. September 19.

This article was published on June 9, 2020.

Michael van der Riet asks a wonderful array of good questions.

– Where did the grains come from, if farming had not yet commenced in that area? Trade with farmers? What goods were traded in return?

Wild wheat and other grains were gathered, much like Native American collecting wild rice. While trading occurred at Göbekli Tepe, it did not include domesticated grains.

– Where did the human bones come from? Am I wrong in supposing from what is said here, that cannibalism was practiced?

Cannibalism was my first thought, but that may not be the case. Some archaeologists believe Göbekli Tepe may have been a sky burial location. The human bodies are often cut into small pieces for the vultures to carry away. It is just too early to tell either way.

– Why did the technology die out? Because the technologists died out, or were eaten?

Archaeological evidence going back perhaps 30,000 years indicates a slow transition from hunter-gathering to farming. There is no evidence of the death of any technology. The idea of a technological transfer 11,600 years ago comes from Graham Hancock. It is not supported by the archeological evidence. The decline only refers to the scale of the enclosures and ignores the advancement towards farming.

– Where were the nearest residential sites? Where were the nearest established farmers?

There are numerous residential sites in the area. No evidence of farming has been discovered in any dating to the time of Göbekli Tepe. It is not clear if they were occupied year round or only seasonally. The closest known farming comes from Nevalı Çori about 30 miles from Göbekli Tepe. It contains the oldest known evidence of farming anywhere at 10,400 years ago. This means farming first began at about the time Göbekli Tepe was abandoned. Nevalı Çori is also were the T-pillars were first discovered.

– What known trade routes crossed the area?

Sitting on a mountain top Göbekli Tepe was almost certainly a trading center, as were the other T-pillar sites in the area. What routes were taken I don’t know.

– What excavating tools were used?

Quarrying and carving were accomplished using flint tools. It is thought that wooden levers and rolling logs were used to dislodge and transport the limestone pillars.

– Limestone weathers rapidly. Why is the site exposed to the elements, without a roof?

It is thought that the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe had roofs. This would have protected the limestone pillars from weathering and erosion. That the enclosures were until recently buried offered protection from the elements. Today the site is protected by a roof.

A fascinating puzzle! Where did the grains come from, if farming had not yet commenced in that area? Trade with farmers? What goods were traded in return? Where did the human bones come from? Am I wrong in supposing from what is said here, that cannibalism was practiced? Why did the technology die out? Because the technologists died out, or were eaten? Where were the nearest residential sites? Where were the nearest established farmers? What known trade routes crossed the area? What excavating tools were used? Limestone weathers rapidly. Why is the site exposed to the elements, without a roof? So many questions, and they said that archeology was a dead science.

Gobekli Tepe has been an eye-opener for Old World archaeologists as they haven’t previously seen examples of monumental architecture made by hunter-gatherer peoples. Here in North America we have had an example of this for some time at a site known as Poverty Point in Louisiana.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poverty_Point

This World Heritage site is a huge array of earthen mounds that were built ca 3700 BP. While not as old as Gobekli Tepe, it was also built by hunter-gatherer people at a very similar stage of social development and technology. The construction of the Poverty Point mounds would have taken at least as much organization and planning over a long period of time as the structures at Gobekli Tepe. Again all accomplished by people who had no agriculture.

I wish more people were aware that Gobekli Tepe isn’t the unique situation that it is usually portrayed as. Fascinating and important, but not the only example of hunter-gatherer peoples accomplishing large construction projects.

Regarding the above mentioned ‘decline’ of megalithic architecture at the site I wouldn’t necessarily draw that as a loss in quality or sophistication. In fact artistically there’s no such downfall noticeable. I’d rather agree that the trend towards smaller monuments may have to be seen against the background of a changing social organisation – probably in context of new subsistence strategies, food-production etc. significantly impacting group structures and time and labour.

When asking for ‘improvement’ here e.g. compared to earlier structures, we also have to keep in mind that these earlier structures may well have been constructed from more perishable material (wood for instance, the carving techniques visible in stone may well have been developed in wood first).

Tamas wrote: “As Hancock notes, the emergence of agriculture at roughly the same time and place as Gobekli Tepe is quite a coincidence.”

Yes, it might be, if that were true. The problem for Hancock is there is no evidence to support the statement. Göbekli Tepe itself is not evidence of a technology transfer at the end of the Younger Dryas. The C14 dates come from the fill and repairs made to the enclosures, not the construction. To be filled and repaired the enclosures must be older, how much older no one knows for sure. Klaus Schmidt thought Göbekli Tepe goes back 15,000 – 14,000 years, and Hancock knows that. This places initial construction closer to the warming at the start of the Bølling–Allerød than the warming at the end of the Younger Dryas. (Personally I find it odd the pseudoscientists switch gears here and advocate for a younger date for Göbekli Tepe, but older dates for the Sphinx and other sites.)

The mystery of Göbekli Tepe stems from a lack of farming. Had they been farmers, then farming began a few thousand years earlier than archaeologists had first assumed, mystery solved. Using circular logic the pseudoscientists believe megalithic architecture itself is proof of farming, and only by farming could they find time to construct the megalithic architecture. This is based on the outdated farming first paradigm. It is also not supported by any evidence. As Jack Harlan discovered back in 1967, this was a land of plenty, providing more food than they could eat.

Science has changed, the farming first paradigm is dead, and Göbekli Tepe helped to kill it. Using cherry picked evidence and an outdated paradigm pseudoscientists claim scientists are incapable of change. To me is seems the other way around. In any case I suggest following the evidence instead of Hancock and the other pseudoscientists.

Thank you for your reply Robert. I really appreciate it.

In response to your points:

You note that “some residue of the advanced technology would remain.” I agree. But isn’t that Gobekli Tepe itself? I’m not saying the people who transferred the technology had anywhere near our levels of knowledge, but perhaps they had far more than was previously assumed of humans that long ago. As Hancock notes, the emergence of agriculture at roughly the same time and place as Gobekli Tepe is quite a coincidence.

The accruing evidence of the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis lends some credence to a mechanism that could have wiped out a possible earlier “civilisation” along with most evidence of its existence. That’s why finding the evidence of increasing quality in architecture at Gobekli Tepe is so important – in my opinion, THE most important task in archeology.

Finally, when I first learnt about Gobekli Tepe I was stunned. It just didn’t make sense. Your article makes some excellent points and is a very reasonable hypothesis, but Hancock’s theory is also plausible (to me, if somewhat radical).

The only way to settle it is to find that buried evidence of the original increase in the quality of the architecture. Until then, we have to keep an open mind and I’m willing to let Hancock’s theory be in contention.

Perhaps of interest to those examining the animal bas reliefs on the pillars, on the pillar often referred to as the Vulture Stela, is depicted bird creatures that are actually the now extinct Dodos. This is of great value to anthropology and biology in placing the Dodo in a much larger setting than its last known range of Mauritius. Only two biological remnants exist in museums along with illustrations. By the nineteenth century, the Dodo had been relegated to near anonymity. Having the Dodo elevated at the top of the Gobekli Tepe pillar might suggest it as a major food source for the people who constructed the “temple.” Also, having so little record (so far) of the bird might suggest a catastrophic food extinction for the people. Perhaps that played into the abandonment of these sites. The vulture image is at the bottom of the same pillar, suggestive of its placement in the cultural observation of the people. But having this ancient record of the Dodo pop up in Turkey is a notable discovery.

Wonderful article thank you Robert. It seems to me we constantly underestimate prehistoric Man. As is true today (Apollo and the moon landings) if a dream or ‘big idea’ gains sufficient traction then a way will be found to achieve it. Hancock and Co. look for miraculous technologies and lost civilisations but I prefer to believe that great things were achieved (and still are) through, imagination, determination and hard work. ‘Chasing the dream’ is as old as Man.

Yes, it is important to keep an open mind instead of jumping to conclusions unsupported by evidence. The decline in scale may be related to the depletion of high quality limestone or perhaps simple a style. Keep in mind that as the scale of the megalithic architecture declined they were slowly advancing towards farming. Perhaps as they transitioned to farming they had less free time to construct the enclosures. I hesitate to extrapolate further until we learn more about such T-pillar sites.

I can’t see how an imagined abrupt technology transfer could result in a decline. It would seem likely some residue of the advanced technology would remain.

You asked “If not, where is the evidence of the original improvement in the architecture?” The answer is it remains buried at Göbekli Tepe and other T-pillar sites.

“the quality and scale of the megalithic architecture declined until eventually the site was abandoned”

This is curious. If the quality of architecture slowly declined, isn’t that the opposite of what we find elsewhere, where the quality tends to improve over time?

A technology transfer that didn’t quite take hold could explain the decline. If not, where is the evidence of the original improvement in the architecture?

We need to keep an open mind and do a lot more research as this is such an important site.

I love this article because it mentions the concept of “affluent gatherers” which I had not heard before. What is the possibility that it was actually those same gatherers that developed the beginning stages of agriculture as a means of keeping their foraging lands alive and prosperous during various stages of climate change? The closest thing I have heard to this idea is the North American Indians keeping forests at bay in order to maintain grasslands for herds of wild grazers.

Well done Bob. In having heard an earlier iteration in a talk, you have really summarized the scholarship in a thorough way.