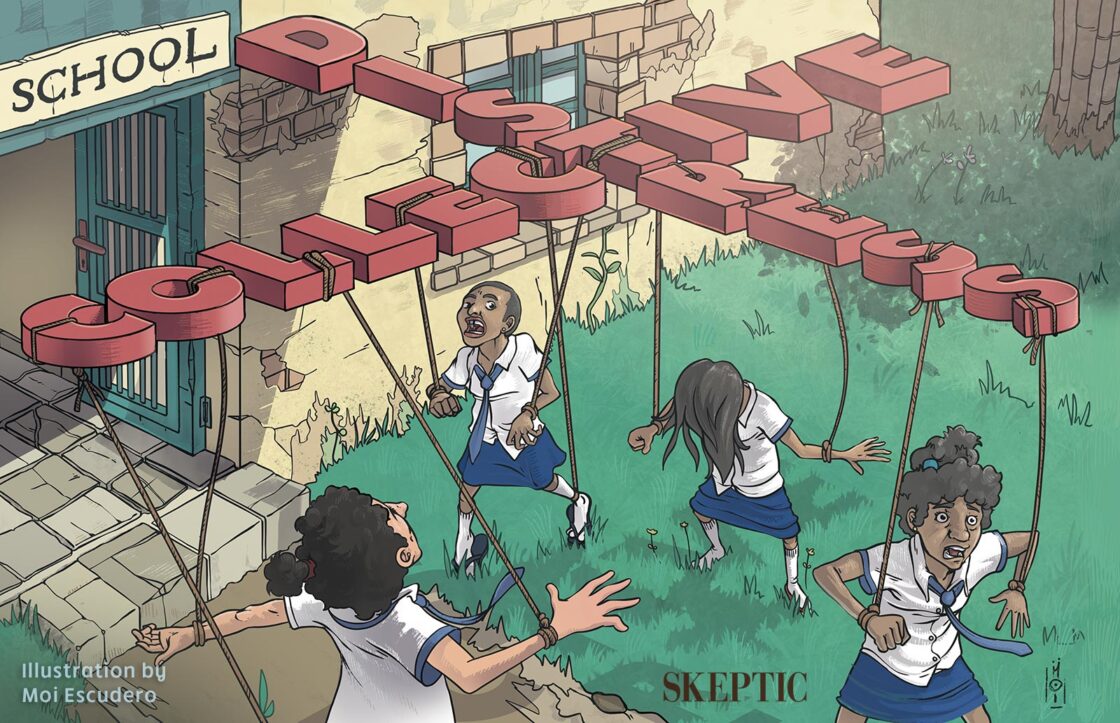

…the basis for these epidemics is the emotional conflict aroused in children who are being brought up at home amidst traditional tribal conservatism, while being exposed in school to thoughts and ideas which challenge accepted beliefs.1

On Monday October 2, 2023, news reports from western Kenya told of a bizarre condition that had swept through St. Theresa’s Eregi Girls’ High School. At least 62 students were hospitalized after exhibiting uncontrollable twitching of their arms and legs, including rhythmic muscle contractions and spasms.2 At times the girls were reported to appear as if possessed by spirits and complained of headaches, dizziness, and knee pain. Many were unable to walk and had to be taken in wheelchairs to waiting ambulances. The strange outbreak occurred in the town of Musoli, about 230 miles northwest of Nairobi. When school opened the next day parents stormed the campus demanding that it be closed until more was known about the outbreak.3 By Wednesday, education officials shut down most of the school as the number of students taken to hospital reached 106.4

International media coverage of the outbreak was often ominous. The Hindustan Times reported: “Mystery Illness in Kenya Leaves School Children with Paralyzed Legs.”5 The Indo-Asian News Service proclaimed: “Mysterious Disease Paralyzes 95 Girls in Kenya.” The Latin American CE Noticias Financieras news agency carried the apocryphal headline: “Nearly 100 Students Walk like ‘Zombies’ in Kenya, Mysterious Illness Raises Alarm Bells.”6

Many people took to social media to blame the COVID-19 vaccine, which was given to the school’s students in July of last year. Others suggested that the girls were faking. Samples of blood, urine, phlegm, and stool were taken, along with throat swabs. All proved to be unremarkable. By Thursday, Kenyan health officials also ruled out the role of infectious disease and instead concluded that they were suffering from “hysteria” in response to stress from upcoming exams.7 The reaction to this episode highlights several misconceptions about outbreaks of “mass hysteria.” As someone who has studied this topic for over three decades, allow me to make some observations.

Observation #1: In attempting to quell an outbreak, never ever use the H-word.

The word “hysteria” is a loaded term that has a checkered past. It was commonly used during the 19th century to stigmatize women as psychologically unstable and emotionally volatile. Most Western physicians and psychiatrists no longer use the term, which has been superseded by more neutral designations such as “mass psychogenic illness,” “mass sociogenic illness,” and “functional neurological disorder.” The condition is used to describe the converting of psychological conflict or trauma into physical symptoms for which there is no organic basis.8

The phenomenon typically occurs in small cohesive groups that are experiencing extraordinary anxiety and is best thought of as a collective stress response that occurs in normal, healthy people. People react much more receptively to being told they were experiencing a stress reaction instead of being told they were involved in an outbreak of “mass hysteria.”

Observation #2: Identify the correct type of outbreak.

Authorities should immediately consider the possibility of a toxin or disease agent, but once these have been eliminated, they should look at the likelihood of mass psychogenic illness. There are two main types of outbreak: anxiety-based and motor-based. The former is common in schools and factories in developed countries where a small cohesive group is suddenly exposed to what is perceived to be a harmful agent. The most common trigger is a strange or unfamiliar odor. Symptoms are benign and short-lived and most commonly include headache, nausea, dizziness, shortness of breath, and general malaise. There is also a conspicuous absence of pre-existing group tension. Most episodes last from only a few hours to a day.

Motor-based outbreaks are most common in less developed countries. They evolve more slowly, often taking weeks or months to incubate. They typically occur in the strictest schools where there is tension between students and administrators or some other conflict. Under such prolonged stress, the nerves and neurons that send messages to the brain become disrupted, resulting in an array of neurological symptoms such as twitching, shaking, convulsions, and trance-like states. This is the same type of outbreak that affected the young Puritan girls in Salem, Massachusetts in 1692 and led to the infamous witch craze. Symptoms will typically subside over time, but in cases where the perceived harmful agent (often demons or spirits) is still believed to be active, episodes can endure for months. There are several cases on record that have persisted for years.9

Observation #3: Find out what is causing the stress and eliminate or at least reduce it.

In the Kenyan episode authorities have blamed exam tension. While this is a common scapegoat and could be a contributing factor, it is rarely the main driver. Since the 1960s, there have been many outbreaks of mass psychogenic illness in Africa.10 Most involve motor-based symptoms that occur in school settings. But not just any school. Christian schools have long been a hotbed of tension and a clash of cultures between the African world and the West. This is the exact setting of the Kenyan episode.

These outbreaks typically revolve around missionary schools that are notorious for ignoring local traditions such as the common practice of ancestor worship, and instead immersing students in Western religious and cultural practices.11 Theologian Jack Partain observes that “Many African theologians—themselves highly educated and westernized Christians—speak of their passionate desire to be linked with their dead and of their own inner struggle.” The belief that ancestors watch their every move and may not always approve, generates conflict for students in missionary schools because while they are taught to worship their ancestors at home, they study the Bible prohibitions at school.12

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 28.4

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

Similar conflicts have also arisen in African Muslim schools. In 1995, over 600 girls at Islamic secondary schools in the Northern Nigerian states of Jigawa and Kano began to exhibit bouts of screaming, crying, foaming at the mouth, and partial paralysis. At other times they would break into spontaneous dancing that resemble performances in Indian masala films. American anthropologist Conerly Casey studied the outbreak and noted that the Bollywood films that the girls were watching commonly had plots that featured the splendor of romantic love, while arranged marriages were still common among the Hausa. Conspicuously, only ethnic Hausa girls were afflicted by the condition. Casey concluded that a driving force behind the outbreak was the psychological conflict generated between the pressure to follow local traditions including arranged marriages, and the desire to emulate the actors who were promoting the glories of romantic love. The episode coincided with other stresses, including a deadly meningitis epidemic that killed thousands. Adding further pressure on the liberal Hausa girls who watched the Indian dance movies was their ostracism by religious and school authorities who portrayed them as being sexually promiscuous and drug users.13

Moving Forward

The recent outbreak in Kenya, along with kindred episodes over the past century, should be seen for what they are: collective manifestations of distress that serve as tension-relieving exercises. They are part ritual, part hysteria, and signal to the wider community that something is seriously amiss. These and other kindred outbreaks are never spontaneous reactions to stress per se; they are always couched in some unique context. It is up to investigators to identify what that is and to address it. However, like so many other outbreaks in Africa involving religious schools over the past century, the recent events in Kenya are yet another manifestation of the traditional superstitions and the legacy of colonialism with its newer superstitions that still haunt the continent like spectres from the past. ![]()

About the Author

Robert E. Bartholomew is an Honorary Senior Lecturer in the Department of Psychological Medicine at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. He has written numerous books on the margins of science covering UFOs, haunted houses, Bigfoot, lake monsters—all from a perspective of mainstream science. He has lived with the Malay people in Malaysia, and Aborigines in Central Australia. He is the co-author of two seminal books: Outbreak! The Encyclopedia of Extraordinary Social Behavior with Hilary Evans, and Havana Syndrome with Robert Baloh.

References

- Ebrahim, G.J. (1968) “Mass Hysteria in School Children, Notes on Three Outbreaks in East Africa.” Clinical Pediatrics 7:437-43

- “At least 62 Eregi Girls Students Hospitalised Over Mysterious Illness.” The Star (Nairobi), Kenya), October 2.

- “Parents Storm Eregi Girls Following Mysterious Illness.” The Star (Nairobi), October 3.

- “Eregi Girls’ High School Closed After ‘Strange Illness.’” The Star (Nairobi), October 4; Lusigi, B. (2023). “Mysterious Disease? Eregi Girls Students Suffering from Panic, Medics Say.” The Standard (Nairobi), October 5.

- Chitre, M. (2023). “Mystery Illness in Kenya Leaves School Children with Paralysed Legs; Over 90 Girls Hospitalised.” Hindustan Times, October 5.

- “Nearly 100 Students Walk like ‘Zombies’ in Kenya, Mysterious Illness Raises Alarm Bells.” CE Noticias Financieras, October 5, 2023.

- Lusigi, B. (2023). “Eregi Girls Students Could be Psychologically Disturbed, Officials say as School Closed.” The Standard (Nairobi), October 5; Makokha, Shaban (2023). “Eregi Students Suffered From Hysteria.” The Daily Nation (Nairobi), October 6.

- Bartholomew, R., & Wessely, S. (2002). “Protean Nature of Mass Sociogenic Illness: From Possessed Nuns to Chemical and Biological Terrorism Fears.” The British Journal of Psychiatry 180(4):300-306.

- Bartholomew, R. E., and Sirois, F. (1996). “Epidemic Hysteria in Schools: An International and Historical Overview.” Educational Studies 22(3):285-311; Bartholomew, R. E., with Rickard, R.J.M. (2014). Mass Hysteria in Schools: A Worldwide History Since 1566. McFarland.

- See, for instance: Rankin, A. M., and Philip, P. J. (1963). “An Epidemic of Laughing in the Buboka District of Tanganyika.” Central African Journal of Medicine 9:167-170; Kagwa, B. H. (1964) “The Problem of Mass Hysteria in East Africa.” East African Medical Journal 41:560-566; Muhangi, J. R. (1973). A Preliminary Report on Mass Hysteria in an Ankole School in Uganda. East African Medical Journal 50:304-309.

- Thomas, R. M. (editor). (1991). International Comparative Education: Practices, Issues, & Prospects. New York: Pergamon Press, p. 204.

- Interview between Robert Bartholomew and Jack Partain, Professor Emeritus in Religion at Gardner-Webb College in Boiling Springs, North Carolina, who taught at the Baptist Seminary of East Africa, Arusha, Tanzania, for 13 years. Conducted by telephone on January 17, 2004. See also: Partain, J. (1986). “Christians and Their Ancestors: A Dilemma of Theology.” Christian Century (November 26), p. 1066.

- Casey, C. (1999). “Dancing Like They Do In Indian Film: Media Images, Possession, and Evangelical Islamic Medicine in Northern Nigeria.” Paper presented at the 98th Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association, Chicago, Illinois, November 17-21; Casey, C. (2017). “Bollywood Banned, and the Electrifying Palmasutra: Sensory Politics in Northern Nigeria.” In Asian Video Cultures: In the Penumbra of the Global, edited by Joshua Neves and Bhaskar Sarkar, pp. 176–197. Duke University Press.

This article was published on October 10, 2023.