Among the most contentious topics in America today is that of kids who identify as transgender: how to understand them, treat them, and make policy based on them. The number of kids with gender dysphoria (GD)—marked distress at an incongruence between gender identity and biological sex—has risen exponentially in the past decade.1 So has the demand for what have come to be known as “gender-affirming” medical interventions: puberty blockers, often followed by cross-sex hormones and sometimes “gender-affirming” surgeries, including the irreversible “top surgery” (in one study, a 13-year-old received a double mastectomy for gender dysphoria2) and sometimes “bottom surgery” such as vaginoplasty.3, 4

This medical model, originated in The Netherlands and known as the “Dutch protocol,” was restricted to kids who had “suffered from lifelong extreme gender dysphoria, are psychologically stable and live in a supportive environment.”5 The protocol was adopted and adapted in the United States beginning in 2007, when the first pediatric gender clinic opened in Boston.6 For years, it was challenging for anyone to access this treatment: The practitioners were few, the stigma enormous. But now, perhaps with increasing acceptance and perhaps lured by the glow of financial opportunities,7 the number of gender clinics has exploded.8 Some of these new practitioners don’t follow the Dutch protocol, opting for the affirmative model, in which young children are sometimes socially transitioned and subsequently allowed to medically and surgically transition using the informed consent model now common for adults—less evaluation, more affirmation. The model aims “to listen to the child and decipher with the help of parents or caregivers what the child is communicating about both gender identity and gender expressions.”9

Many sources of mainstream media, most notably those with a political bent, present this issue as a left/right battle. They portray liberals as supporting trans kids and their access to medical interventions in order to save their lives.10 They present anyone who objects to these treatments as conservative, transphobic bigots, who call these treatments experimental and dangerous11 and want to ban all medical interventions.12 The two tweets (above) capture the sentiments of these polarizing sides. What was just a few years ago a topic of debate is now a test of loyalty.13

This binary framing politicizes the scientific research and makes it hard for both laypeople and medical and psychological practitioners to ask questions and find answers about how GD develops; how to treat it; its relation to transgender identity; and how safe and effective the treatments are. How should the primum non nocere principle be applied in these cases? Is “do no harm” postponing hormones and surgery until adulthood, or is it easing present suffering through starting medical treatment in adolescence or younger?

In fact, there are many viewpoints on how to answer those questions, including those of liberals and trans people with concerns about the medical model and conservatives who embrace it. Meanwhile, some of the most experienced practitioners don’t want to ban medical interventions, but they do believe there are abuses and misuses of them.14

Some young people are helped by medical interventions, at least in the shortterm,15 since we have little longterm data on those treated since 2007; others are deeply harmed16 by them. Some people look at the growth of gender- affirming care and see transgender people finally getting the treatments they want or need. Others see a medical scandal of epic proportions. Some believe medicalizing gender dysphoric youth is child abuse; others think withholding it is child abuse. Somewhere in between are the multiple and competing narratives that most of the mainstream media has ignored. Here are just a few of them.

Being Trans and Having Gender Dysphoria Are Not Interchangeable

One of the biggest challenges with even talking about these issues comes from the lack of common language. Gender,17 for instance, can be a synonym for biological sex, or it can mean expectations and norms based on biological sex, or an internal sense of self, separate from biological sex: that is, gender identity.

Trans or transgender is an umbrella term that can include anyone defying gender norms or people formerly known as transsexuals,18 who change their bodies to appear as the opposite sex (or, increasingly, some people who identify as non-binary19 and change their bodies to appear ambiguously sexed).

It’s commonly accepted that not all trans people have gender dysphoria. Less accepted is the idea that someone with gender dysphoria isn’t necessarily trans, or that identifying as trans, or having gender dysphoria, may not persist. But as the following research shows, the latter has often been the case.

A New and Growing Cohort

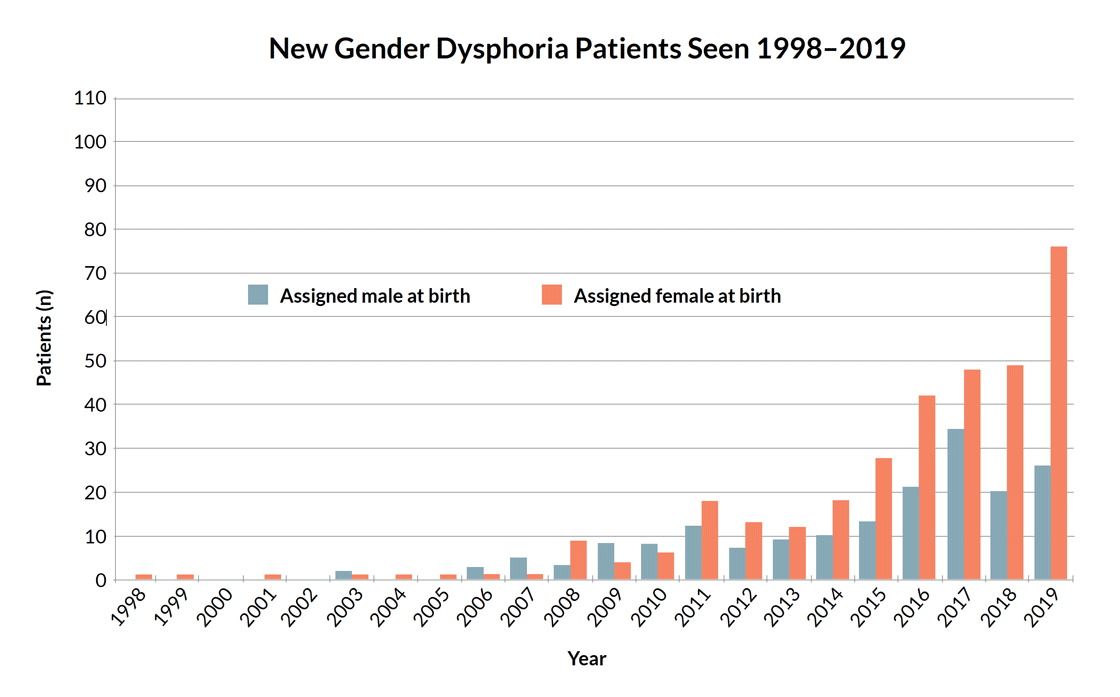

In much of the developed world, referrals to gender clinics and diagnoses of gender dysphoria have been on a steep incline in a short period of time.

The graph (above) by Trans Youth CAN!,20 a study of youth referred for puberty blockers and hormones in Canada, shows a tiny number of young people—the majority male—sought care until 2007 at a gender clinic in British Columbia. Since then, the number of referrals has grown more than tenfold, and the majority are now female. The Netherlands saw a similar trend.21 The UK’s Gender Identity Development Service reports an almost 4,000 percent increase in ten years,22 also shifting from majority males to females, the great bulk of them teenagers. In the past, the majority of referrals were young children or adult males.23

Many of these teens have co-occurring mental health issues,24 like depression, anxiety, trauma,25 or eating disorders, or are neuro-diverse (for example, ADHD, dyslexia, or on the autism spectrum), and they appear to differ from prior cohorts, who had childhood- onset GD. There is almost no research on this population, which has prompted some people to ask if it is ethical or safe to apply a medical protocol designed for a different kind of patient to them.26

What accounts for this demographic shift? Some argue it is increasing awareness and acceptance of trans people, and access to language and information; perhaps gender dysphoria and transgender identities were far more common than people knew. Others say it is the influence of social media, popular culture, and social contagion,27 leading some struggling people to self-diagnose with gender dysphoria and land on transition as the answer. A doctor and public health researcher, Lisa Littman, conducted an exploratory study based on parental reports28 (a common method29) and found entire peer groups declaring transgender identities after social media immersion. She coined the term “rapid-onset gender dysphoria” (ROGD) to describe the phenomenon of this new population in a dispassionate, descriptive way.

Many object to the term and its implications, categorizing ROGD as a fake diagnosis invented by the right wing to undermine teens’ transitions.30 Some papers31 and groups say data do not support ROGD and suggest not using the term because it can be employed to deter people and politicians from supporting gender-affirming medical care.32 Some clinicians I’ve talked to don’t want to use the term ROGD because of its political baggage, but may acknowledge that this is a new and complex population that’s much harder to treat.33 Still others don’t want there to be any research into why someone identifies as trans, because they feel it presents being trans as a pathology,34 a problem that needs solving, instead of presenting trans identities as variations, not deviations.

The Unspoken Relationship Between Gender and Sexuality

Under the current zeitgeist, gender is often defined as an internal sense of self, unrelated to sexuality. But decades of psychological and anthropological research suggest that gender and sexuality are often deeply intertwined.35

There is, for example, which sex you identify as and which sex you are attracted to. But it’s even more complicated than that. So called “third genders”36 like the muxes of Mexico, the Samoan fa’afafine, Brazil’s travestí or the hijra of India are androphilic (that is: attracted to men), traditionally feminine males.37 These alternative categories seem to protect feminine androphilic males in places where open homosexuality is either illegal or not tolerated, but gender nonconformity is. Some of Samoa’s masculine, gynephilic (attracted to women) females, who may be referred to as butch lesbians elsewhere, have referred to themselves as trans men; they seem to have less acceptance than fa’afafine.38

In Europe and North America, some psychologists and sexologists working in gender clinics in the 1980s and 1990s divided those seeking sex reassignment into two main categories39 of patients: “homosexual transsexuals” and “non-homosexual transsexuals.” The former group tended to include traditionally feminine boys and traditionally masculine girls, who were so from a very young age, and were later attracted to members of their own sex. In several longterm studies, most prepubescent children referred to clinics, for what was then known as gender identity disorder, “desisted;” that is, the majority were gay, not trans.40

There is a paucity of quality evidence on the outcomes of those presenting with gender dysphoria.

The latter cohort, “non-homosexual transsexuals,” often didn’t present until puberty or much later, and rarely had a history of childhood gender nonconformity, cross-sex identity, or dysphoria. Most got an erotic charge from imagining themselves as women, which manifested in everything from wanting to wear women’s clothes to masturbating to the idea of themselves lactating or menstruating. Sexologist and psychologist Ray Blanchard called this “autogynephilia,” or “love of oneself as a woman.”41 (Many trans women object to the idea of autogynephilia and feel it paints them as perverted, though Blanchard meant it only as a descriptor and not a moral judgment.42 Some autogynephiles, however, embrace it.43)

There are many more than two types of trans people now, including today’s cohort of young people who tend to have much more complex mental health issues. But today’s youth are also generally taught that gender and sexuality are not linked, when past research shows transgender identity or gender dysphoria were often related in some way to sexuality.44 There can be a connection of some kind, but no causation.

High Desistance Rates in Older Research

As noted, in past studies the vast majority of kids with early-onset (prepubertal) gender dysphoria desisted,45 and many grew up to be gay. In a recently published 15-year follow-up study of boys referred to a gender clinic for what was then called gender identity disorder, 88 percent of them desisted, and 63.6 percent were later same-sex attracted.46

But those kids were not socially transitioned to live as the opposite sex or another social category, as many children are today. Some clinicians believe that social transition will increase the chances of more severe dysphoria at puberty, therefore creating medicalized trans children who would otherwise have been gay.47 One study noted an association between persistence and social transition.48 Some more recent research shows much higher rates of persistence—96 percent in one case—which likely includes socially transitioned kids. And the older desistance research has been critiqued for a number of reasons, including that it is “built upon bad statistics, bad science, homophobia and transphobia.”49

While some research notes that it appears that “the persistence, insistence, and consistency of statements, and behaviours in childhood”50 helps predict whether GD will continue or not, no clinician, child, or parent can know for certain how to forecast from childhood GD or from gender nonconformity. There is no clinical test.

The proposed eighth edition of the Standards of Care for how to treat trans and gender-diverse people, created by the World Professional Association of Transgender Health, notes that childhood gender diversity is normal. WPATH writes: “Diverse gender expressions in children cannot always be assumed to reflect a transgender identity or gender incongruence.”51 However, they do not mention desistance.

It used to be thought that the older a young person came out as transgender or experienced gender dysphoria, the more likely they’d persist, but that was perhaps because some of those studied were autogynephilic men whose sexual orientation was intertwined with gender, and sexuality is generally considered to be difficult to change. But today, as more teens come out, the majority girls, that research does not necessarily apply.

Other Countries are Rethinking Medical Approaches—Not for Political Reasons

Several countries, or major medical centers in those countries, are banning or limiting puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and gender-affirming surgeries for children. Finland has severely restricted the practice,52 and in at least one pediatric gender clinic in Western Australia a patient now needs a court order to medically transition.53

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) changed its position in 2021 to promote thorough mental health evaluation before proceeding medically. The move doesn’t come from politics but a review of the evidence. Their guidance states that “There is a paucity of quality evidence on the outcomes of those presenting with gender dysphoria. In particular, there is a need for better evidence in relation to outcomes for children and young people.”54

Sweden’s Karolinska Hospital and several other Swedish hospitals have stopped providing gender-affirming medical treatment for kids under 18, except in clinical trials.55 The reason? Several kids were severely harmed in what they called “healthcare-related injuries,” including a teenager with osteoporosis, who stopped growing.56 Per Medscape, “This decision comes amid growing unease in some quarters regarding the speed at which hormonal treatment of children with gender dysphoria has become accepted as the norm in many countries, despite what critics say is a lack of evidence of any benefit, plus known harms, of treatment.” A young woman named Keira Bell successfully won a case against the UK’s gender identity development service for facilitating the transition she came to regret,57 arguing that children could not understand what they were consenting to. Medical interventions for under-16s were briefly stopped, save for those with court orders. But the ruling was overturned; the court said “it was for clinicians rather than the court to decide on competence [to consent].”58

As a 2015 article in the Journal of Adolescent Health noted, “no consensus exists whether to use these early medical interventions.”59

Trans, Suicide, and Mental Health: Confounding Variables

A paper in Pediatrics suggested an “inverse association between treatment with pubertal suppression during adolescence and lifetime suicidal ideation among transgender adults who ever wanted this treatment,”60 though some have noted the data came from a “low-quality survey,”61 and were based on a convenience, not representative, sample of self-selected participants (the same reason the ROGD survey is often critiqued). As the paper’s author noted, “Limitations include the study’s cross-sectional design, which does not allow for determination of causation.” Other criticisms were that the paper didn’t establish that people had actually received the treatment, since many claimed to be over 18 when receiving the treatment.

Still, the finding is not surprising considering many young people have been told these drugs will make them feel better and they desperately want them, so a placebo effect may account for those provisional outcomes.

A recent study in the Journal of Adolescent Health examined “associations among access to GAHT [Gender Affirming Hormone Therapy] with depression, thoughts of suicide, and attempted suicide among a large sample of transgender and nonbinary youth.”62 The authors found that those who wanted puberty blockers and didn’t get them had worse mental health than those who wanted them and got them. This, too, was a convenience sample. However, the participants’ mental health scores were low, all around. Some 44 percent of those who received puberty blockers (PBs) seriously considered suicide in the past year, versus 57 percent of those who didn’t receive them. Fifteen percent of those who received PBs attempted suicide, versus 23 percent of those who didn’t. Another and more likely explanation is the increasing number of trans youth with co-occurring mental health issues, so the trans variable may be confounding, not causal.

No clinician, child, or parent can know for certain how to forecast from childhood GD or from gender nonconformity. There is no clinical test.

Many people believe that youth are at risk if their pronouns aren’t respected.63 The Trevor Project reported that “Transgender and nonbinary youth who reported having pronouns respected by all of the people they lived with attempted suicide at half the rate of those who did not have their pronouns respected by anyone with whom they lived.”64 Almost every media outlet notes that trans and gender dysphoric kids have a higher rate of suicidal ideation,65 and one study found an attempted suicide rate of over 50 percent for female-to-male adolescents.66 Another study found that gender-referred children were 8.6 times more likely than non-referred children to selfharm or attempt suicide.67 These rates, however, are similar to those of children with other mental health struggles.68 So, again, transgender identity, or gender dysphoria, could be confounder variables, not causal.

These studies do not establish causation between transition and preventing suicide, only correlation. The research on suicide is in no way conclusive, and some parents have reported that clinicians told children that if they didn’t transition, they’d be at risk for suicide; self-fulfilling prophecy may be at work considering how contagious suicidal ideation is among young people.69 Most recent studies are not longterm enough to know lasting effects of medical intervention on suicidal ideation, depression, or dysphoria.

As well, even the findings linking trans identities to suicide are not always replicated. One Swedish study of over 6,000 people with GD found only .6 percent, or 0.006, had died by suicide, and notes that “people with different psychiatric conditions generally have even higher risks of suicide than people with gender dysphoria.”70 The UK’s Gender Identity Development Service notes suicide is “extremely rare.”71

One recent study found both positive and negative psychological changes correlated to puberty blockers.72 A study of adults (albeit with research from 1973 through 2003, when there was less cultural understanding of trans issues), showed “mortality for sex-reassigned persons was higher during follow-up,” post-surgical transition and that “Sex-reassigned persons also had an increased risk for suicide attempts.”73

What is Past is Not Necessarily Prologue: Why the Dutch Protocol Does Not Apply to Today’s Demographic

We’re often told that medical interventions alleviate gender dysphoria and that regret is rare. In a 2014 study of kids medically transitioned using the Dutch protocol, most found their gender dysphoria improved and their psychosocial functioning was akin to their gender conforming peers, at least in the early assessments.74 (There is, though, a critique of the study’s methodology.)75

These kids, however, were all carefully assessed and thoroughly informed—and excluded if they had other serious mental health issues. Most had childhood onset GD and were not socially transitioned.76 The way some clinics operate today is much different, assuming that any child who says they are trans is so.77 As Thomas Steensma of the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria at Amsterdam UMC, an expert in the Dutch protocol, told a Dutch newspaper in 2021: “the rest of the world is blindly adopting our research.78

The question of whether children can understand and consent to these complications and lifelong changes is hotly debated.

Children in the U.S. may still need support letters from therapists or doctors to access hormones or surgeries, but the practitioners may not be carefully evaluating children or directing those with co-occurring mental health issues or trauma, who may not appear to be good candidates for medical transition, toward non-medical options.

Unclear Longterm Physical Effects of Medical Transition

Puberty blockers are often discussed as a way to “hit the pause button” on puberty and give kids time to decide if they want to proceed medically. But they are largely the first step in medicalization. In one study, 98 percent of kids went from puberty blockers to cross-sex hormones.79 Though puberty blockers are often discussed as reversible—meaning a child will go through their endogenous puberty if he or she goes off them—the longterm effects are either unknown or negative, impacting bone density80 and fertility.81 Little is known about lasting effects on brain development or cardiovascular health.

The safety of and satisfaction with hormonal and surgical transition for children is largely unknown, and wildly variant for adults. Many participants in studies were lost to follow up,82 which can skew conclusions and outcomes. One study “found insufficient evidence to determine the efficacy or safety of hormonal treatment approaches for transgender women in transition.”83 Medical transition has been linked to reduced sexual function,84 corrective surgery,85 incontinence,86 and heart attacks.87

That doesn’t mean some transsexual adults (those who have had medical interventions) don’t find the complications worth it; some studies show improved happiness post-medical transition.88 The question of whether children can understand and consent to these complications and lifelong changes is hotly debated.

No One Knows the Rates of Regret, But the Number of Detransitioners is Rising

The dominant narrative is that regret and detransition—returning to living as one’s biological sex, post medical transition—are rare. One review of studies claimed that less than one percent of those who’d had gender-affirming surgeries regretted them.89 (A rebuttal to the study called it erroneous, inflated and miscalculated.)80

Most (but not all) of those study subjects were carefully evaluated,91 sometimes forced to participate in the “real life test,”92 living as the opposite sex before being allowed by therapists and doctors to transition, to try to establish that it is what they really wanted. If they detransitioned later, it was sometimes attributed to stigma,93 access to care, or financial problems—external, not internal, issues.

But the number of people detransitioning because of internal regrets is growing. They are speaking out on social media94 and forming networks and groups.95 A new study in the Journal of Analytical Psychology,96 as well as a new study on 100 detransitioners by Lisa Littman in the Archives of Sexual Behavior,97 find that more people are detransitioning because they realized that they never should have altered their bodies in the first place. Littman found that 71 percent of respondents said that they believed that medical transition was the only path toward feeling better; did not want to be associated with their natal sex; or said their body felt wrong. They understood transition as the way to “become their true selves.”

Participants said they experienced pressure to transition; therapists presented transition as a panacea; doctors pushed hard for drugs and surgery; and friends told them they should transition. Some 60 percent of detransitioners returned to identifying as their biological sex once they understood that the biological categories of male and female could accommodate them. More than half of respondents said they had not been properly evaluated by doctors or therapists, and 65.3 percent said their evaluations did not investigate whether trauma played a role in their desire to transition. Almost three-quarters did not report their regret to their doctors or therapists.

We are not keeping careful statistics on detransition or regret—or satisfaction—so we don’t know how common or rare it is.98 Littman’s study, like many in this field, is based on a convenience sample, so while it offers some glimpses into this phenomenon, it is not conclusive. She advises: “More research is needed to understand this population, determine the prevalence of detransition as an outcome of transition, meet the medical and psychological needs of this population, and better inform the process of evaluation and counseling prior to transition.”

Exploratory Therapy Is Not Conversion Therapy

Conversion therapy—trying to reprogram sexuality— has been clearly shown to be ineffective and harmful for gay people and is considered unethical.99 Some people claim that providing therapy for kids who identify as transgender is akin to conversion therapy— exploring rather than accepting, they say, assumes it’s worse to be transgender than cisgender (meaning having a gender identity that aligns with biological sex). At least 25 states have some kind of ban on conversion therapy, though the term is ill-defined.100

But others argue that conversion therapy for sexuality is very different than exploratory therapy to examine the source of gender dysphoria since, as outlined above, there are many different sources, and many people do not suffer from it persistently.101 And accepting oneself as gay requires no permanent medical intervention. Some therapists who practice exploratory therapy are afraid to identify themselves, lest they be labeled transphobic. The newly formed Gender Exploratory Therapy Association helps connect kids suffering from gender dysphoria with a therapist who will neither affirm nor convert.102

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 27.1

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Supporting children who identify as transgender, or who are gender dysphoric, is correlated with improved mental health outcomes.103 But support is not synonymous with affirmation, nor does it imply lack of careful evaluation and/or exploratory therapy. As schools sometimes facilitate secret social transitions without informing parents,104 and some activists advocate for family abolition105—believing families are standing in the way of children’s transition and mental health —some families are divided when a child comes out, much the way the country is.106 The more the debate is presented as right versus left, or transphobia versus trans rights activism, rather than science versus belief, the more harm will be done to families and kids, who deserve the right to know all the information in order to make an educated decision.

What’s clear about the evidence is that it’s not very clear at all. ![]()

About the Author

Lisa Selin Davis is the author of Tomboy: The Surprising History and Future of Girls Who Dare to Be Different. She has written op-eds, essays and articles for the New York Times, Washington Post, CNN, Salon and many other publications, and is the author of two novels, Belly and Lost Stars. She is at work on a book about the history of the housewife ideal—where it came from and how it affects us still.

References

- https://gids.nhs.uk/number-referrals

- Johanna Olson-Kennedy, Jonathan Warus, Vivian Okonta, et al. “Chest Reconstruction and Chest Dysphoria in Transmasculine Minors and Young Adults: Comparisons of Nonsurgical and Postsurgical Cohorts.” JAMA Pediatrics, May, 2018. https://bit.ly/3Jfj0oV

- Christine Milrod, “How Young Is Too Young: Ethical Concerns in Genital Surgery of the Transgender MTF Adolescent,” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 11, no. 2 (February 1, 2014): 338–46, https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12387

- Christine Milrod and Dan H. Karasic, “Age Is Just a Number: WPATH-Affiliated Surgeons’ Experiences and Attitudes Toward Vaginoplasty in Transgender Females Under 18 Years of Age in the United States,” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 14, no. 4 (April 2017): 624–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.02.007

- Annelou L C de Vries and Peggy T Cohen-Kettnis. “Clinical Management of Gender Dysphoria in Children and Adolescents: The Dutch Approach.” Journal of Homosexuality 59(3), 2012: 301–320. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22455322/

- https://on.bchil.org/3FlNnI2

- “U.S. Sex Reassignment Surgery Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Gender Transition (Male to Female, Female to Male), and Segment Forecasts, 2020–2027.” Grand View Research. December 2020. https://bit.ly/3yRNfxC

- “Interactive Map: Clinical Care Programs for Gender-Expansive Children and Adolescents,” HRC, accessed January 6, 2022, https://www.hrc.org/resources/interactive-map-clinical-careprograms-for-gender-nonconforming-childr

- Marco A. Hidalgo et al., “The Gender Affirmative Model: What We Know and What We Aim to Learn,” Human Development, 56, no. 5 (2013): 285–90, https://doi.org/10.1159/000355235

- Tim Fitzsimons. “Puberty Blockers Linked to Lower Suicide Risk for Transgender People.” NBC News, January 24, 2020. https://nbcnews.to/3Hp6dyP

- “State Policy Brief: Save Adolescents from Experimentation (SAFE) Act.” Family Research Council. June 24, 2021. https://bit.ly/3Jf1a5B

- “LGBTQ Policy Spotlight: Efforts to Ban Health Care for Transgender Youth.” Movement Advancement Project. April 2021. https://bit.ly/3EmZ8wr

- Mark Angelo Cummings. “Transitioning is for Those Who Can Vote and Drink.” New York Times, June 18, 2015. https://nyti.ms/3ySMNPL

- Laura Edwards-Leeper and Erica Anderson. “The Mental Health Establishment is Failing Trans Kids.” Washington Post. November 24, 2021. https://wapo.st/32gBd59

- Anna Martha Vaitses Fontanari et al., “Gender Affirmation Is Associated with Transgender and Gender Nonbinary Youth Mental Health Improvement,” LGBT Health 7, no. 5 (July 1, 2020): 237–47, https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2019.0046

- https://www.cbsnews.com/video/60minutes-2021-05-23/

- Lisa Selin Davis. “What Are Your Kids Learning About Gender?” Broadview, September 8, 2021. https://bit.ly/3sw9Nmc

- Bonnie Kime Scott et al., Women in Culture: An Intersectional Anthology for Gender and Women’s Studies (John Wiley & Sons, 2016).

- Julie Compton. “Neither Male nor Female: Why Some Nonbinary People are ‘microdosing’ Hormones.” NBC News. July 13, 2019. https://nbcnews.to/3H5CuKU

- https://bit.ly/3mqOr5R

- Chantal M. Wiepjes, Nienke M. Nota, Christel J.M. de Blok, Maartje Klaver, Annelou L.C. de Vries, S. Annelijn Wensing-Kruger, Renate T. de Jongh, Mark-Bram Bouman, Thomas D. Steensma, Peggy Cohen-Kettenis, Louis J.G. Gooren, Baudewijntje P.C. Kreukels, Martin den Heijer, The Amsterdam Cohort of Gender Dysphoria Study (1972–2015): Trends in Prevalence, Treatment, and Regrets, The Journal of Sexual Medicine,Volume 15, Issue 4, 2018, Pages 582–590, ISSN 1743–6095, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.01.016

- https://bit.ly/3FsAADF

- https://bit.ly/3eBq4yp

- Kasia Kozlowska, Georgia McClure, Catherine Chudleigh, et al. “Australian Children and Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria: Clinical Presentations and Challenges Experienced by a Mulitidisiciplinary Team and Gender Service.” Human Systems. April 22, 2021. https://bit.ly/3qoeBr7

- Riittakerttu Kaltiala-Heino et al., “Gender Dysphoria in Adolescence: Current Perspectives,” Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics 9 (March 2, 2018): 31–41, https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S135432

- William J Malone, Paul W Hruz, Julia W Mason, Stephen Beck, Letter to the Editor from William J. Malone et al: “Proper Care of Transgender and Gender-diverse Persons in the Setting of Proposed Discrimination: A Policy Perspective”, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 106, Issue 8, August 2021, pages e3287–e3288, https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab205

- “Opinion: When It Comes to Trans Youth, We’re in Danger of Losing Our Way,” The San Francisco Examiner, accessed January 6, 2022, https://www.sfexaminer.com/opinion/are-we-seeing-aphenomenon-of-trans-youth-social-contagion/

- Lisa Littman. “Parent Reports of Adolescents and Young Adults Perceived to Show Signs of a Rapid Onset of Gender Dysphoria.” PLoS One. August 16, 2018. 14(3). https://bit.ly/3Jinew0

- https://bit.ly/3FFHAxn

- Jennifer Finney Boylan. “Coming Out as Trans Isn’t a Teenage Fad.” New York Times. January 8, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/08/opinion/trans-teen-transition.html

- Greta R. Bauer, Margaret Lawson, and Daniel Metzger. “Do Clinical Data from Transgender Adolescents Support the Phenomenon of ‘Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria?” The Journal of Pediatrics. November 15, 2021. https://www.jpeds.com/article/S0022-3476(21)01085-4/fulltext

- https://www.caaps.co/rogd-statement

- https://bit.ly/3yRPL72

- “IFGE 2009 Workshop: ‘Disordered’ No More: Challenging Transphobia in Psychology, Academia and Society,” accessed January 6, 2022, http://ai.eecs.umich.edu/people/conway/TS/IFGE2009/Disordered_No_More.html

- Michael J. Bailey and Kenneth J. Zucker. “Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior and Sexual Orientation: A Conceptual Analysis and Quantitative Review.” Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 43–55. https://bit.ly/3Fs4J62

- Francisco R. Gomez, Scott W. Semenyna, Lucas Court, and Paul L. Vasey. “Familial Patterning and Prevalence of Male Androphilia Among Istmo Zapotec Men and Muxes.” PLoS One. Feb. 21, 2021, 13(2). https://bit.ly/3sw02Va

- Paul L. Vasey and Doug P VanderLaan. “Birth Order and Male Androphilia in Samoan fa’afafine.” Proc Biol Sci. June 7, 2007. https://bit.ly/3muwW50

- https://youtu.be/6g_q-Zt7Mks

- Ray Blanchard. “Typology of Male-to-Female Transexualism.” Archives of Sexual Behavior, 14, 247–261. June, 1985. https://bit.ly/3poZyyo

- Riittakerttu Kaltiala-Heino et al., “Gender Dysphoria in Adolescence: Current Perspectives,” Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics 9 (March 2, 2018): 31–41, https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S135432

- https://bit.ly/3qfMLxa

- Julia Serano. “Autogynephilia: A Scientific Review, Feminist Analysis, and Alternative ‘embodiment fantasies’ Model.” The Sociological Review, August 10, 2020. https://bit.ly/3ssRDll

- Anne A. Lawrence. “Autogynephilia and the Typology of Male-to-Female Transexualism: Concepts and Controversies.” European Psychologist, 22, 39–54. 2017. https://bit.ly/3EC8CV3

- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-differencebetween-sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity/

- Jiska Ristori and Thomas D. Steensma. “Gender Dysphoria in Childhood.” International Review of Psychiatry. January, 2016, 28(1): 13–20. https://bit.ly/3Ha7oli

- Devita Singh, Susan J. Bradley and Kenneth J. Zucker. “A Follow-Up Study of Boys with Gender Identity Disorder.” Frontiers in Psychiatry. March, 2021. https://bit.ly/3eiEeUM

- Kenneth J. Zucker. “Debate: Different Strokes for Different Folks.” Child and Adolescent Mental Health. June, 2019. https://bit.ly/3yXfLhu

- Thomas D. Steensma et al., “Factors Associated with Desistence and Persistence of Childhood Gender Dysphoria: A Quantitative Follow-up Study,” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 52, no. 6 (June 2013): 582–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.03.016

- https://bitli.pro/1kJjg_b95da5e9; https://bitli.pro/1kJjf_af36284b

- Andreas Kyriakou, Nicolas C. Nicolaides, and Nicos Skordis. “Current Approach to the Clinical Care of Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria,” Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis 91, no. 1. 2020, 165–75, https://bit.ly/3feZCLj

- https://bit.ly/3H7j6Nv

- https://bit.ly/3Jf58ev

- Bernard Lane. “Judges to Oversee Transgender Teen Treatment.” The Australian, July 20, 2021. https://bit.ly/3ekv8H1

- https://bit.ly/3qnXZ2Y

- Lisa Nainggolan. “Hormonal Tx of Youth with Gender Dysphoria Stops in Sweden.” Medscape Medical News, May 12, 2021. https://wb.md/3qfiH4Y

- https://bit.ly/33OldaJ

- https://bit.ly/3mvTiCT

- https://bit.ly/3ppcGU5

- Lieke Josephina Jeanne Johanna Vrouenraets et al., “Early Medical Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Gender Dysphoria: An Empirical Ethical Study,” Journal of Adolescent Health 57, no. 4 (October 1, 2015): 367–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jadohealth.2015.04.004. https://www.jahonline.org/article/S1054-139X(15)00159-7/fulltext

- Jack L. Turban, Dana King, Jeremi M. Carswell, and Alex S. Keuroghlian. “Pubertal Suppression for Transgender Youth and Risk of Suicidal Ideation.” Pediatrics, February 2020. https://bit.ly/32vap0K

- Michael Biggs. “Puberty Blockers and Suicidality in Adolescents Suffering from Gender Dysphoria.” Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2020, 49(7), 2227–2229. https://bit.ly/3pnqyy0

- Amy E. Green, Jonah P. DeChants, Myeshia Price, and Carrie K. Davis. “Association of Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy with Depression, Thoughts of Suicide, and Attempted Suicide Among Transgender and Nonbinary Youth.” Journal of Adolescent Health. December 14, 2021. https://bit.ly/32BYe2g

- Deborah Temkin and Claudia Vega. “Research Shows the Risk of Misgendering Transgender Youth.” Child Trends. October 23, 2018. https://bit.ly/3pndpoI

- https://bit.ly/3pnqMoQ

- Lisa Rappaport. “Trans Teens More Likely to Attempt Suicide.” Reuters. September 17, 2018 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-transgender-teen-suicide-idUSKCN1LS39K

- Russell B. Toomey, Amy K. Syvertsen, and Maura Shramko. “Transgender Adolescent Suicide Behavior.” Pediatrics, Vol. 142, No. 4, October 2018. https://bit.ly/3Je2F3W

- Madison Aitken, Doug P. Vanderlaan, Lori Wasserman, and Sonja Olivera Stojanovski. “Self-Harm and Suicidality in Children Referred for Gender Dysphoria.” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(6). https://bit.ly/32vaS30

- Hannah R. Lawrence, Taylor A. Burke, et al. “Prevalence and Correlates of Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts in Preadolescent Children: A US Population-Based Study.” Translational Psychiatry. September, 2021. https://go.nature.com/3yWBg1V

- “Suicide Contagion and the Reporting of Suicide: Recommendations from a National Workshop,” accessed January 5, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/ mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00031539.htm

- https://bit.ly/3ehQTYa

- https://gids.nhs.uk/evidence-base

- Polly Carmichael, Gary Butler, Una Masic, et al., “Short-term outcomes of pubertal suppression in a selected cohort of 12 to 15 year old young people with persistent gender dysphoria in the UK.” PLoS One. February, 2021. https://bit.ly/3Jqevbs

- Dhejne C, Lichtenstein P, Boman M, Johansson AL, Långström N, Landén M. Long-term follow-up of transsexual persons undergoing sex reassignment surgery: cohort study in Sweden. PLoS One. 2011 Feb 22;6(2):e16885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016885. PMID: 21364939; PMCID: PMC3043071

- Annelou L C de Vries, Jenifer K. McGuire, Thomas D Steensma, et al. “Young adult psychological outcome after puberty suppression and gender reassignment.” Pediatrics, October, 2014. https://bit.ly/33K816G

- Daniela Danna, “Gender-Affirming Model Still Based on 2014 Faulty Dutch Study,” January 1, 2021, 223–39, https://doi.org/10.15167/2279-5057/AG2021.10.19.1169

- 76 Annelou L.C. de Vries, “Challenges in Timing Puberty Suppression for Gender-Nonconforming Adolescents,” Pediatrics 146, no. 4 (October 1, 2020): e2020010611,

- https://youtu.be/uwBdkln-ciw

- https://www.voorzij.nl/more-research-is-urgentlyneeded-into-transgender-care-for-young-peoplewhere-does-the-large-increase-of-children-come-from/

- Polly Carmichael, Gary Butler, Una Masic, et al. “Short-term outcomes of pubertal suppression in a selected cohort of 12 to 15 year old young people with persistent gender dysphoria in the UK.” PLoS One. February, 2021. https://bit.ly/3sLp4Qz

- Ahmed Elhakeem, Monika Frysz, Gake Tilling, et al. “Association Between Age at Puberty and Bone Accrual From 10 to 25 Years of Age.” JAMA Netw Open. August 2019.

- Philip J. Cheng, Alexander W. Pastuszak, et al. “Fertility conerns of the transgender patient.” Transl Androl Urol. June, 2019. https://bit.ly/3yV7Y3A

- D’Angelo R. Psychiatry’s ethical involvement in gender-affirming care. Australas Psychiatry. 2018 Oct;26(5):460–463. doi:10.1177/1039856218775216. Epub 2018 May 21. PMID: 29783857

- Claudia Haupt, Miriam Henke, Alexia Kutschmar, et al. “Antiandrogen or estradiol treatment or both VOLUME 27 NUMBER 1 2022 SKEPTIC.COM 15 during hormone therapy in transitioning transgender women.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. November, 2020. https://bit.ly/3yVaCX4

- Kerckhof ME, Kreukels BPC, Nieder TO, Becker- Hébly I, van de Grift TC, Staphorsius AS, Köhler A, Heylens G, Elaut E. Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunctions in Transgender Persons: Results from the ENIGI Follow-Up Study. J Sex Med. 2019 Dec;16(12):2018–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.09.003. Epub 2019 Oct 24. Erratum in: J Sex Med. 2020 Apr;17(4):830. PMID: 31668732

- Paulette Cutruzzula Dreher, Daniel Edwards, Shaun Hager, et al. “Complications of the neovagina in maleto- female transgender surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis with discussion of management.” Clinical Anatomy. March, 2018. https://bit.ly/3muFPLw

- N. Massiri, M. Maas, M. Basin. “Urethral complications after gender reassignment surgery: a systematic review.” International Journal of Impotence Research. June, 2020.

- Talal Alzahrani, Tran Nguyen, Angela Ryan, et al. “Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Myocardial Infarction in the Transgender Population.” Circulation. April 2019. https://bit.ly/3pmdM30

- Elahe Fallahtafti, Meisam Nasehi, et al. “Happiness and Mental Health in Pre-Operative and Post-Operative Transsexual People.” Iranian Journal of Public Health. December, 2019. https://bit.ly/30U6Q3A

- Valeria Bustos, Samyd Bustos, et al. “Regret after Gender-affirmation Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence.” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. March, 2021.

- Pablo Expósito-Campos and Roberto D’Angelo, “Letter to the Editor: Regret after Gender-Affirmation Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence,” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery—Global Open 9, no. 11 (November 2021): e3951, https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000003951

- Henriette A Delemarre-van de Waal and Peggy T. Cohen-Kettenis. “Clinical management of gender identity disorder in adolescents: a protocol on psychological and paediatric endocrinology aspects.” European journal of Endocrinology. November, 2006. https://bit.ly/3mqVxHG

- Justin Cascio. “Origins of the Real-Life Test.” Transhealth. January, 2003. https://bit.ly/3qkOwcA

- Jack L. Turban, Stephanie S. Loo, Anthony N. Almazan, and Alex S. Keuroghlian. LGBT Health. Jun 2021. 273–280. http://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2020.0437

- https://bit.ly/3EqV4vo

- https://www.reddit.com/r/detrans/

- Lisa Marchiano. “Gender Detransition: A Case Study.” The Journal of Analytical Psychology. November, 2021. https://bit.ly/33VM2de

- Lisa Littman. “Individuals Treated for Gender Dysphoria with Medical and/or Surgical Transition Who Subsequently Detransitioned: A Survey of 100 Detransitioners.” Archives of Sexual Behavior. October, 2021. https://bit.ly/33Oku9r

- Pablo Exposito-Campos and Roberto D’Angelo. “Letter to the Editor: Regret After Gender-AffirmationSurgery: A Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis of Prevalence.” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. November, 2021. https://bit.ly/3pmaYTu

- Drescher, Jack, Ariel Shidlo, and Michael Schroeder. Sexual conversion therapy: Ethical, clinical and research perspectives. Vol. 5. No. 3–4. CRC Press, 2002. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Sexual_Conversion_Therapy/LzBRKEk_160C

- https://bit.ly/3ppfErH

- Roberto D’Angelo et al., “One Size Does Not Fit All: In Support of Psychotherapy for Gender Dysphoria,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 50, no. 1 (January 2021): 7–16,

- https://bit.ly/30XSkIc

- Jason J. Westwater, Elizabeth A. Riley, and Gregory M. Peterson. “What about the family in youth gender diversity? A literature review.” International Journal of Transgenderism. August, 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6913651/

- https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/nov/22/transgender-children-wisconsin-school-parents

- https://twitter.com/gp_jls/status/1430222843573383169

- Katelyn Burns. “What the battle over a 7-year-old trans girl could mean for families nationwide.” Vox, November 11, 2019. https://bit.ly/3mxwmmP

This article was published on May 25, 2022.