In this week’s eSkeptic:

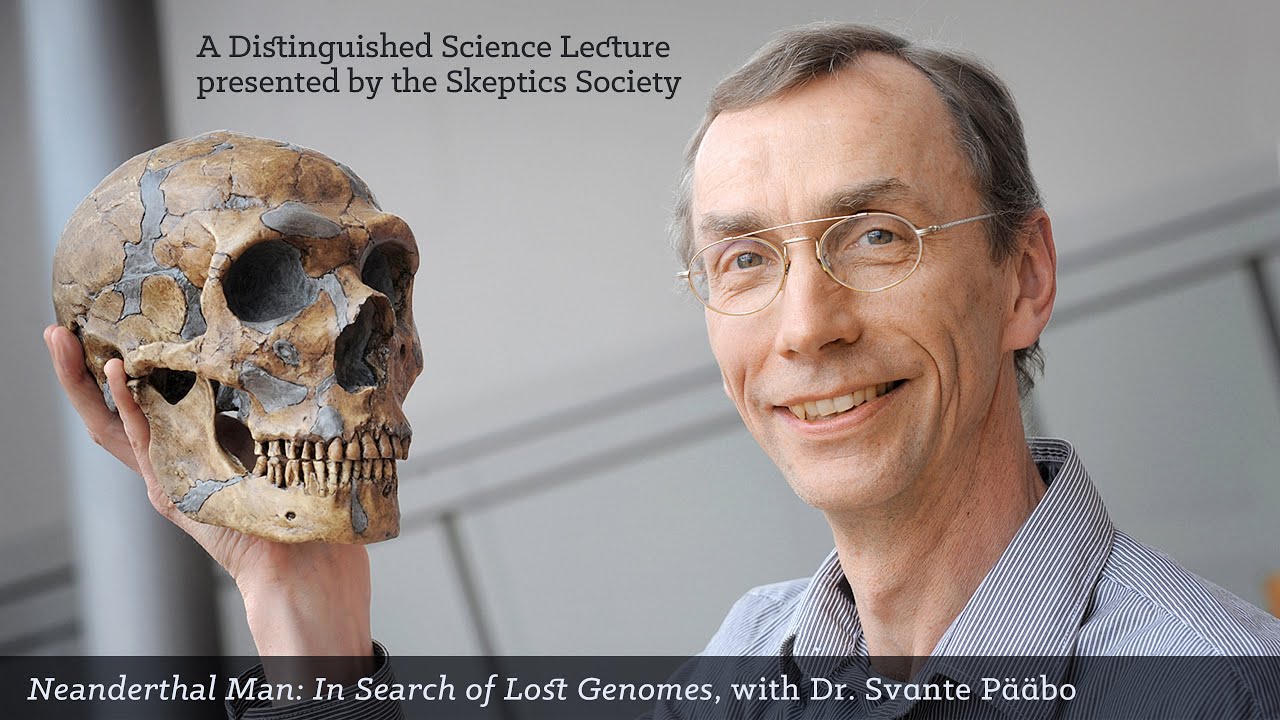

DISTINGUISHED SCIENCE LECTURE

Svante Pääbo — Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes

Svante Pääbo is the founder of the field of ancient DNA and is the director of the department of genetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig. In Neanderthal Man he tells the story of his mission to answer the question of what we can learn from the genes of our closest evolutionary relative, culminating in his sequencing of the Neanderthal genome in 2009. We learn that Neanderthal genes offer a unique window into the lives of our hominin relatives and may hold the key to unlocking the mystery of why humans survived while Neanderthals went extinct. Drawing on genetic and fossil clues, Pääbo explores what is known about the origin of modern humans and their relationship to the Neanderthals and describes the fierce debate surrounding the nature of the two species’ interactions. Order Neanderthal Man from Amazon.

You play a vital part in our commitment to promote science and reason. If you enjoyed this Distinguished Science Lecture, please show your support by making a donation.

Shots of Awe

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 236

This week on Skepticality, Derek has a conversation with Jason Silva. Jason is known for his work as the host of the Emmy Nominated National Geographic channel television show, Brain Games. Jason is a self-proclaimed “wonder junkie” who has been pushing the ideas of inspiration, science, technology, and imagination not only through television but also via new media, TED Talks and anywhere else he can. Find out more about what made Jason set out to inspire others with such passionate intesity.

Photo by David Patton

About this week’s eSkeptic

Last week, the James Randi Educational Foundation’s “The Amazing Meeting 2014” conference in Las Vegas brought together many of the most engaging voices in science and skepticism for a challenging and joyful celebration of ideas. The Skeptics Society was in the spotlight, with Michael Shermer, Donald Prothero, and Junior Skeptic’s Daniel Loxton taking the stage for feature presentations.

In this week’s eSkeptic, we share the text of Loxton’s well-received speech on skeptical history, titled “A Rare and Beautiful Thing.” Although designed as a live multimedia presentation, we hope this distilled format will give a sense of the passion behind this unusual piece.

Share this article with friends online.

Subscribe | Donate | Watch Lectures | Shop

A Rare and Beautiful Thing

by Daniel Loxton

Hello! Thanks for having me.

I work for Michael Shermer and Pat Linse at the Skeptics Society, where I’ve done the Junior Skeptic section of Skeptic magazine for about 12 years, writing on everything from alien abduction to crystal skulls to the Curse of King Tut.

Generally, I spend my time making things, mostly for kids. I make pictures, often with my friend Jim Smith; I write stories; I do research.

To the best of my ability, I do what skeptics have done for decades:

- Study paranormal and pseudoscientific claims;

- Solve mysteries;

- Tell the public what we have learned.

As a footnote to doing scientific skepticism, I also do some writing about this kind of work. I do a little blogging, and I’ve written op-eds (PDF) and historical explorations (PDF) about the principles and ethics and craft of what we do.

My inward-looking discussions in articles and tweets and interviews often have to do with the challenges and “scope” of traditional, scientific skepticism—describing the uniqueness of the skeptical project; exploring its contested boundaries with other parallel rationalist movements; and identifying areas for clarification, development, and improvement.

But today I want to see this strange, rare jewel, with all its flaws and inclusions, in a different kind of light. Rather than talking about what makes skepticism difficult, I want to argue that skepticism is beautiful.

This may seem like a strange term to use. Skepticism has a reputation as blunt and plodding. Even skepticism’s friends often treat it as something a little embarrassing. As Stephen Jay Gould observed, “Skepticism or debunking often receives the bad rap reserved for activities—like garbage disposal—that absolutely must be done for a safe and sane life, but seem either unglamorous or unworthy of overt celebration.”

I love the comparison with trash collecting, because it emphasizes the unending labor, unsavory subject matter and practical usefulness of the skeptical project. It’s a comparison many have made.

“The scientific debunker’s job may be compared to that of the trash collector,” said science fiction writer L. Sprague de Camp in 1986. “The fact that the garbage truck goes by today,” he wrote, “does not mean that there will not be another load tomorrow. But if the garbage were not collected at all, the results would be much worse, as some cities found when the sanitation workers went on strike.”

There may seem little beauty in this image… but as an artist, it’s my job to look for it!

Happily, artists are not the only ones who do this, as Richard Feynman once explained in reference to the beauty of a flower. “There are all kinds of interesting questions,” he said, “that come from a knowledge of science, which only adds to the excitement and mystery and awe of a flower.”

Now, it’s one thing to find beauty in a flower.

But I believe it is also there to be seen in skepticism’s noble tradition of necessary service.

When I talk about “beauty” I’m obviously stepping outside of the empirical framework of scientific skepticism. I’m speaking about that work as a person who comes to my job with personal values, moral intuitions, and sources of meaning and purpose.

These are what motivate me to do this work.

I’d like to play some remarks from JREF President DJ Grothe [video clip from this lecture]:

And you know that I’ve never heard someone who’s really passionate about comic books…even if they’re obsessed with comic books—I’ve never heard anyone refer to their love of comic books as “a calling.” I hear skeptics, honest, use that term frequently. … The passion I feel for magic is unlike the passion I feel for skepticism. It lacks a component that my love of skepticism has. Why is that? I submit that you are here today…and that my passion for advancing skepticism in society is different than my love of comic books or maybe playing video games on my Xbox 360…because skepticism is more than just a hobby, I’ll argue. And it’s more than just a club…. I’ll argue today that you’re involved in skepticism—here it is—because skepticism is a humanism.

I happen to identify personally as a secular humanist. But I know, and Grothe knows, that the skeptical community is broader than that. The people in this audience identify with a diversity of faith traditions and schools of thought.

Grothe used “humanism” here in this very broad, perhaps universal sense:

People from all backgrounds feel moved by goodness—and some people see goodness in skepticism.

Film critic Roger Ebert observed that the visceral emotional experience of “Elevation”—of spiritual uplift— comes “not through messages, or happy endings or sad ones, but in moments when characters we believe in—even an animated robot garbageman—achieve something good.”

I’d go even further: we feel that straight-to-the-spine sense of Elevation when we see someone choose to try to do something good.

Ebert also once said [video clip from documentary film Life Itself]:

For me the movies are like a machine that generates empathy. It lets you understand hopes, aspirations, dreams, and fears. It helps us to identify with the people who are sharing this journey with us.

Stories do that. True stories do that.

When I saw this trailer, I was struck strongly by this phrase—“a machine that generates empathy”—because I remembered saying something similar.

In 2007, I was a regular listener to the popular Skeptics Guide to the Universe podcast. Today I count the hosts as friends, but at that time they were the voices of strangers. Yet I felt a powerful sense of community, of fraternity with these people, because they spoke to the subjects of my passions, and because their ideas and laughter came into my home every week. And so I found myself tremendously moved when I heard the news of the death of co-host Perry DeAngelis, and heard the sorrow in the voices of his friends. I found myself writing to them, asking,

What does one say to strangers about the loss of their close friend? …I don’t know. But I’m struck by the importance…of what Perry built with you. I’m one of those who believes wholeheartedly in skepticism as a project to reduce harm to real people.

Something like the SGU is a fair sort of thing to leave behind: not a hobby, not an entertainment, but a machine for helping people.

If skepticism is a machine for helping people, it’s a machine of tremendous antiquity. Not long ago, I saw this tweet from comedy talk-show host Craig Ferguson:

I realize I’m late to the party (by nearly 2000 years) but iconoclastic rascal Lucian of Samosata may be my new favorite skeptic.

— Craig Ferguson (@CraigyFerg) March 24, 2014

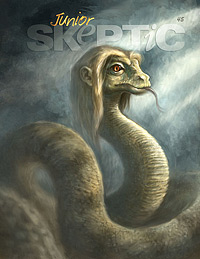

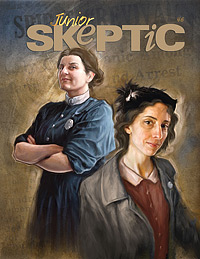

Cover of Junior Skeptic 45, bound inside Skeptic 17.4.

Lucian was a second-century Roman writer and debunker. I published a Junior Skeptic in 2012 about Lucian and his James Randi-like battle against a celebrity psychic, Alexander of Abonoteichus, who founded a snake-god cult.

It’s a case which is not well known in these forgetful days, but which has been a touchstone for skeptics for centuries.

In 1935, psychologist and activist skeptic Joseph Jastrow wrote about Lucian and Alexander in his book Error and Eccentricity in Human Belief:

“The temptation to deceive is as old as the human race,” he wrote, “and so is the inclination to succumb to deception, which is credulity.”

To this we might add that the thirst to investigate is just as old. For as Jastrow goes on,

“There is an instance of it, classical in every sense, which, written eighteen hundred years ago, reads like a modern exposé, even to the details of ways and means.”

To read Lucian’s book on Alexander the Oracle-Monger is to be shocked by familiarity. I almost beg you to read it—it’s short—but I’ll tell you some of that story:

… Alexander was a con man who graduated to cult leader using tricks that are still used in fortunetelling and mediumship today. Lucian describes him as an exceptionally handsome man with a clear, deep, persuasive voice:

In understanding, resource, acuteness,” Lucian recalled, “he was far above other men; curiosity, receptiveness, memory…— all these were his in overflowing measure. But he used them for the worst purposes.

Establishing himself as a prophet, Alexander spread rumours in Abonoteichus about an imminent miracle—about the advent of a god on Earth. When he had stoked up a fever of public interest, he ran out one morning into the city marketplace wearing only a loin-cloth. He climbed up onto a high altar— wild-eyed, raving at the crowd. He cried out that the time had come! A god was coming to Abonoteichus right now!

He ran to a temple construction site, followed by an amazed throng of men, women and children. Singing hymns, Alexander splashed into the mud and water of the excavation for the foundation for the temple. He plunged a bowl into the mud, and in triumph, lifted out a miracle.

It was a goose egg.

When Alexander broke open the egg into his hollowed palm, it was seen to contain a live snake. It was, he said, the newborn god.

[T]he crowd could see it stirring and winding about his fingers,” Lucian wrote, and “they raised a shout, hailed the God, blessed the city, and every mouth was full of prayers — for treasure and wealth and health and all the other good things that he might give.

Well, this bit with the egg was a magic trick. Lucian explained how it was done. The egg was blown out in advance, resealed with a small snake inside, and planted at the construction site to be found on cue.

But here’s the thing—this exact same effect is used to devastating impact by psychic scammers today. In the modern Boojoo or “egg curse” scam, fortunetellers hatch snakes, worms, hair or blood from an apparently ordinary egg or tomato, revealing that the mark—or her money—is cursed, and must be cleansed by the fortuneteller.

Every year, countless people lose their savings to a scam that goes back to days of the Roman Empire!

A few days later Alexander opened shop in a dimly-lit audience chamber. Miraculously, the snake god was now fully grown—its writhing body played by a large python, and its human-like head by a handcrafted prop. The wonderstruck crowd was hustled past this special effect before they could look too closely.

But this was all stage-dressing, patter for the trick that Alexander built his business on, which was fortunetelling. Alexander understood, Lucian said, that “human life is under the absolute dominion of two mighty principles, fear and hope, and…whether a man is most swayed by the one or by the other, what he must most depend upon and desire is a knowledge of futurity.”

Which Alexander was happy to sell.

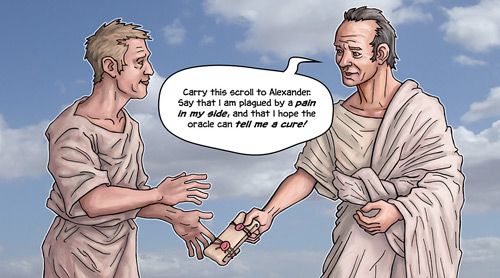

He “directed everyone to write down in a scroll…what he especially wished to learn, to tie it up, and to seal it with wax or clay….”

Alexander took these sealed questions into an inner chamber. There, in communion with the god, he wrote an answer on the outside of each scroll, and returned it “with the seal upon it, just as it was”—apparently unopened.

Well, this is a trick too, and psychics still perform it today.

There are many variations, but the basic secret is, as Lucian put it, obvious: Alexander “contrived various methods of undoing the seals, read the questions, answered them as seemed good, and then folded, sealed, and returned them, to the great astonishment of the recipients.”

Lucian described a few of the techniques he knew for doing this, such as sliding a hot needle under a wax seal. If the scroll couldn’t be opened, the questioner could be pumped for clues, or answers could be written in mystic gibberish. (The services of an interpreter were available for an additional fee.)

Today, skeptical investigators such as Joe Nickell often seek to trap psychics who perform readings of sealed messages. They may provide false information for the psychic to incorporate into their reading, or attempt to mark the message in a way that would reveal substitution, or to make the message difficult to open without leaving a sign.

Eighteen hundred years ago, Lucian did the exact same thing.

“Many such traps, in fact, were set for him by me and by others,” Lucian wrote.

He sent well-sealed scrolls which asked one thing, but allowed his servants to believe they asked something else. When Alexander’s answers came back, they reflected the information that could be pumped from the servants who delivered the scrolls, not what was written inside. On another occasion, Lucian sent money for eight questions, and got back eight meaningless answers. But the tamperproof scroll he sent asked only this:

“When will Alexander’s imposture be detected?”

In some instances it was detected. Like other psychics, Alexander was ultimately making it up—and he was frequently, sometimes horrifically, wrong.

In a case that mirrors modern psychic Sylvia Browne’s incorrect declaration that kidnapping victim Shawn Hornbeck had been murdered, Alexander pronounced that a missing young man from a wealthy family had been killed by his servants. Those poor people were tried, found guilty, and executed by means of “wild beasts.”

But the young man was alive. He’d been traveling.

When this was discovered, another skeptic stood up in a large crowd and bravely confronted Alexander about the blood on his hands. Alexander’s response? He ordered his audience to stone the skeptic to death — which they attempted to do.

Despite opposition from skeptics, Alexander’s influence only grew. He bound wealthy clients into unshakable loyalty. He advised military planners. He sold invented cures, and spells of protection from plague.

The authorities refused to take action. Alexander’s psychic career continued until he died wealthy and powerful at almost 70 years old—which we know because Lucian told us about it.

Why did Lucian do that?

What made him study and record and critique Alexander’s career of paranormal deception?

While Alexander lived, the answer was one that has smoldered in the hearts of skeptics for almost two thousand years:

When unfounded claims burn out of control, people get hurt.

Alexander was dangerous. He preyed on people. His lies sent innocent people to their annihilation. He sold deadly false confidence in times of plague, sent soldiers into disaster when they might have been kept from harm’s way.

There was a clear need for someone to do something—and it fell on skeptics like Lucian to try.

Lucian continued this work of skeptical scholarship even after Alexander’s death.

Why?

Because Lucian was not alone in that work. His book on Alexander was written at the request of his friend Celsus, who had written debunking books of his own, exposing the fakery of sorcerers.

An account of Alexander’s trickery was no “trifling task,” Lucian objected to his friend. Also, he had ethical qualms about writing it:

I confess to being a little ashamed both on your account and my own. There are you asking that the memory of an arch-scoundrel should be perpetuated in writing; here am I going seriously into an investigation of this sort.

A scam artist like Alexander did not deserve study, Lucian said, “but to be torn to pieces in the amphitheatre by apes or foxes, with a vast audience looking on.”

But Lucian told himself that there was value in this work—that there were constructive lessons to learn and teach in the study of scam artists and occult beliefs.

We may be glad that he did.

“Lucian was far more than an exposer of false prophets,” wrote Joseph Jastrow in 1935. “He is entitled to remembrance as one of the first students of the strange beliefs of men.”

We are all students in that same school of the weird and the wild and the wicked. And for centuries, students of skepticism have turned back to learn from older texts.

Carl Sagan explicitly linked the practices of modern psychics, including those described in Lamar Keene’s The Psychic Mafia, to the criminal practices of Alexander. Sagan also linked the “useful work” of the modern skeptical movement to Lucian and his colleagues.

Philosopher David Hume retold the story of Lucian and Alexander in 1748 in his Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. In doing so, Hume wrote what may be the single most important sentence ever written about why skepticism exists as a movement.

Hume wrote,

“But, though much to be wished, it does not always happen, that every Alexander meets with a Lucian, ready to expose and detect his impostures.”

For as long as there have been claims that sound too good to be true, there have been people who felt drawn to the task of finding out. And always, throughout history, at all times, those people have been too scattered, and too few.

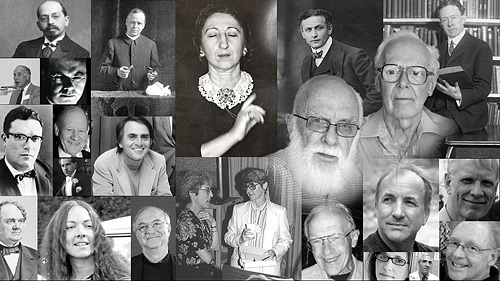

But the dawn of an organized skeptical movement brought light to a shared horizon. It unified what had been scattered. It drew together people—very different in many ways—who found they were talking about the same things.

Scientific skepticism recognized a literature of common insights, connected the people who studied the fringe, and showed that their investigations collectively comprised a distinct field of study.

There are people in this room with us today who have fought for skepticism for forty, fifty, even sixty years.

How many careers were spent, how many lives were lived in service of skepticism before even those people were born?

Few people begin to realize the depth or the breadth or the scale of the skeptical efforts which have taken place in previous generations.

The man (above) with the chalkboard is Joseph Rinn, demonstrating mediumistic trickery for a press syndicate in 1920. For decades, Rinn was in the thick of every important occult battle in America. He formed a New York-based skeptics group in 1905.

Rinn was present for confessions by the Fox sisters, the founders of Spiritualism.

He took Harry Houdini to his first séance.

And while young Houdini was busy building his showbiz career—was himself performing the talking to the dead routine he would later realize “bordered on crime”—Rinn was arguing as a skeptic in the media that, “Wonderful phenomena demand wonderful evidence….”

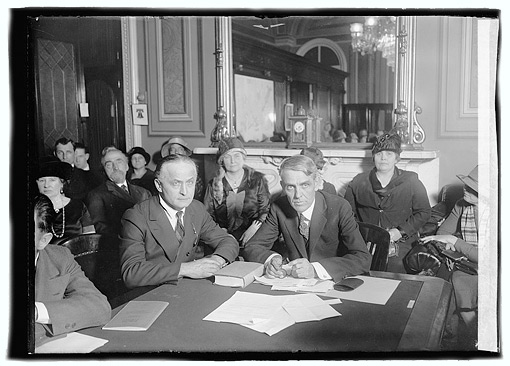

When Rinn’s old friend Houdini finally did get into the fight, he arrived as a mighty champion. He brought skill and knowledge, and wealth and fame. Houdini studied and investigated and wrote books, and gave demonstrations.

Harry Houdini and Kansas Senator Arthur Capper, 2/26/26 (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

He went to Congress to fight for tougher laws against fraudulent fortunetellers in the nation’s capital. He fought with passion, and gravity of purpose.

And he lost.

There is a strange and heartbreaking beauty in that.

Houdini’s mission continued even after his death in 1926.

Rose Mackenberg, the head of Houdini’s team of undercover agents, continued to pursue psychic scam artists as a private investigator, lecturer, and consulting expert for decades. Having investigated crimes of all types, Mackenberg believed “the most vicious criminals in America are the charlatans who betray and plunder their heartsick victims in the name of the dear, departed dead”—especially those who work in organized gangs.

She called them “conscienceless scoundrels devoid of even the most elementary feelings of decency and pity,” and was proud to have helped put many behind bars.

It was her life’s work.

In 1931, inspired by Houdini’s example, the Society of American Magicians joined forces with the NYPD to try to rid New York City of its burden of paranormal scammers.

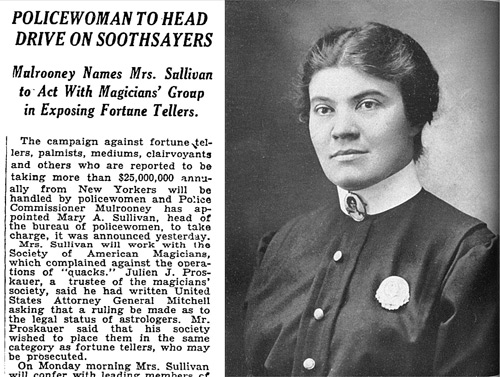

Left: clipping from 1931, July 18, New York Times, p9. Right: Detective Mary Sullivan, from her autobiography My Double Life: The Story of a New York Policewoman (1938)

For more on the lives and skeptical careers of Rose Mackenberg and Mary Sullivan, see Junior Skeptic 46, bound inside Skeptic 18.1.

The officer in charge was the head of the Policewomen’s Bureau, Detective Mary Sullivan, a pioneer who joined the force in 1911. She was the second woman in the NYPD ever to be raised to Detective, First Grade, and the first to have served on the Homicide Squad.

At that time, policewomen specialized in undercover work on crimes such as shoplifting, quack medicine, and fortunetelling. When she joined with the magicians, Sullivan had already spent 20 years busting psychic scams as a cop:

I had a personal reason for finding the fortuneteller hunt attractive,” she wrote. “When I was a child my five-year-old brother wandered out of the house after mass one Sunday and was never seen again. Tortured by uncertainty as to whether he was alive or dead, my mother turned to fortunetellers for guidance. For years they led her on from one false hope to another, telling her that he would be brought home by shipboard the following spring; that a dark woman was holding him prisoner in a basement; that we would see him on the street when he was fifteen years old. The repeated disappointments my mother suffered caused her as much pain as if the boy had been lost to her many times instead of only once. My recollection of all this made it doubly pleasant to me to flash my badge before an astonished seeress and tell her that she and her paraphernalia were about to depart for a ride.

Reducing this intimate kind of harm matters. Seeking justice for victims matters—especially when few people care.

As magician Jamy Ian Swiss asked on this stage [video clip from this lecture]:

How can you say psychic fraud doesn’t matter when there is a steady stream of news stories about victims who give up life savings to psychic con artists? Do you think it mattered to the victims?

There is much more to skeptical history than we can talk about today. There is more than I will learn in my lifetime.

Here are just a few of the skeptical books published before I was born. [Sixty book titles in reverse chronological order from 1974 to 1580.]

Skepticism is a bright, shining thread that runs through the whole of the human tapestry. We can follow that thread of curiosity and conscience—in places with difficulty—through the entire length of the history of civilization.

Skepticism is part of who we are. It is part of who we always have been. It is a deep and essential part of our better nature.

And it is beautiful to me.

Scientific skepticism connects us with lives lived, struggles undertaken by men and women who lived and fought and questioned and challenged—and sometimes risked everything—decades, even centuries ago. We are brothers and sisters to those who have—for millennia—chosen this particular way to help.

We are connected to those who refused to accept the deceitful cruelties of their times— connected to the people who felt called to light candles…because they cursed the darkness!

There is beauty in this choice in life—beauty in the attempt to push back the night.

But candles do more than hold back the darkness. That small, warm light also allows us to take our children by the hand and show them how big and how wonderful the universe really is.

Every child deserves to see from those great heights. It’s a view that belongs to everyone.

And the moral calling to share that view is beautiful.

Skepticism is lifted up by the belief that knowledge can help people, that truth is better than falsehood—that there is more to the world than cynicism and deceit.

As Michael Shermer has said, skepticism “is a celebration of the scientific spirit and the joy inherent in exploring the world’s great mysteries even when final answers are not forthcoming. The intellectual journey matters, not the destination.”

Thank you. ![]()

Order These Top Notch Books

from TAM2014

- Evolution vs. Creationism: An Introduction

- by Eugenie C. Scott

- Brainwashed: The Seductive Appeal of Mindless Neuroscience

A Los Angeles Times Book Prize Finalist - by Sally Satel & Scott Lilienfeld

- 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology: Shattering Widespread Misconceptions About Human Behavior

- by Lilienfeld, Lynn, Ruscio, and Beyerstein

- Mistakes Were Made (but not by me): Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts

- By Carol Tavris

- Do You Believe in Magic? Vitamins, Supplements,

and All Things Natural - by Paul A. Offit, M.D.

- Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life

A 1995 National Book Award Finalist - by Daniel C. Dennett

- Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon

A New York Times Bestseller - by Daniel C. Dennett