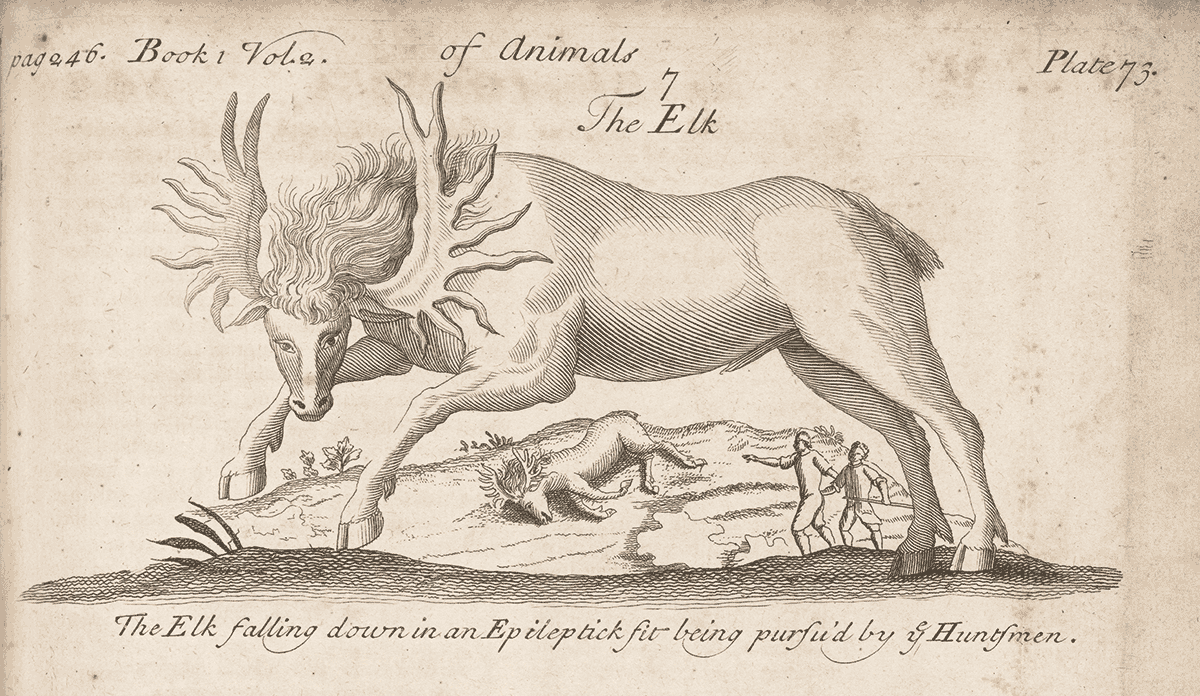

In a 1725 copper etching, huntsmen approach a moose felled by epilepsy. (A Compleat History of Druggs originally written in French by Monsieur Pomet, translated and expanded by Mess. Lemery and Tournefort. London, 1725. Printed with permission of the Huntington Museum, Pasadena, CA.) Click image (above) to enlarge it.

About this week’s eSkeptic

Have you ever gone cow tipping, or do you know someone who says they have? Where in the world did this strange idea come from? In this week’s eSkeptic, Pat Linse examines the surprising origins of cow tipping. This article was originally published in Skeptic magazine 20.1 (2015).

Pat Linse is an award winning illustrator who specialized in film industry art before becoming one of the founders of the Skeptics Society, Skeptic magazine, and the creator of Junior Skeptic magazine. As Skeptic magazine’s Art Director, she has created many illustrations for both Skeptic and Junior Skeptic. She is co-editor of the The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience.

The Legend of the Falling Beast

Cow Tipping’s Surprising Origins

by Pat Linse

Istarted to hear the story as soon as I moved to Los Angeles in the 1970s: “Have you ever gone cow tipping?” the twenty-something guy would brag. “It’s hilarious! You drive out into the country late at night and find a bunch of sleeping cows—they sleep standing up with their legs locked, you know—and wham!—you shove them over before they know what’s happened. Boy, are they surprised!”

This article was originally published in Skeptic magazine 20.1 (2015).

Of course cow tipping is an urban legend as explained in the article above, from from Junior Skeptic # 5, bound within Skeptic magazine issue 7.2 (pages 100–101). Cows don’t sleep standing up, their legs do not lock, and they are generally too big for a puny human to topple. They don’t even sleep at night, resting instead in five minute naps thoughout the 24-hour day.

One of the oddest parts of the cow tipping story is the claim that a cow sleeps standing up “on locked legs” that are so ridged and unbending that it can be easily pushed over. Where in the world did this strange idea come from? It turns out that the story comes from Europe and it’s been around for at least 2000 years. The famous Roman general Julius Caesar recorded this fantastic account of how to hunt easy-to-tip animals that lived in the dense forests that covered what is now southern Germany:

There are also (animals) which are called elks [The animal known as a moose in America is called an elk in Europe]. The shape of these, and the varied color of their skins, is much like roes [deer], but in size they surpass them a little and are destitute of horns, and have legs without joints and ligatures; nor do they lie down for the purpose of rest, nor, if they have been thrown down by any accident, can they raise or lift themselves up. Trees serve as beds to them; they lean themselves against them, and thus reclining only slightly, they take their rest; when the huntsmen have discovered from the footsteps of these animals whither they are accustomed to betake themselves, they either undermine all the trees at the roots, or cut into them so far that the upper part of the trees may appear to be left standing. When they have leant upon them, according to their habit, they knock down by their weight the unsupported trees, and fall down themselves along with them. Ceasar’s Gallic Wars—Book 6, Chapter 27 [6.27] about 58–51 BCE

This same hunting tall tale was also told in ancient times about the elephant and the asian tapir. About 100 years after Caesar another Roman, Pliny the Elder, wrote about an animal with a long nose he called an “achlis,” that seemed to have both moose and elephant traits:

The North, too, produces herds of wild horses, as Africa and Asia do of wild asses. There is also the achlis, which is produced in the island of Scandinavia; it is not unlike the elk, but has no joints in the hind leg. Hence, it never lies down, but reclines against a tree while it sleeps; it can only be taken by previously cutting into the tree, and thus laying a trap for it, as otherwise, it would escape through its swiftness. Its upper lip is so extremely large, for which reason it is obliged to go backwards when grazing; otherwise, by moving onwards, the lip would get doubled up. Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, 77 CE.

The story that an elk could be easily captured because it couldn’t get back up after it fell to the ground was passed down through the centuries as part of medical folklore. Books listing medical herbs and magical cures declared that elk suffered from “the falling disease” which we know today as epilepsy. Legend had it that an elk could cure its own epilepsy by striking itself with its hoof, so it was thought that taking powered elk’s hoof as a medicine, or wearing a ring carved from elk’s hoof on your finger, or even wearing a gold pendant set with a scrap of hoof would ward off the disease.

The story that European elk were susceptible to fits of falling made it across the Atlantic to the Americas. As late as the mid-1800s the famous author and medical doctor Oliver Wendal Holmes complained that some superstitious American physicians still prescribed elk’s hoof (or even horse’s hooves) for epilepsy. Did the old falling elk legend inspire the modern cow tipping story? Both are a bragging tale where a large animal is captured at night because of its unusual sleeping habits, but that in itself might not be enough to say the stories are related.

But both stories depend on the same ridiculous idea—that the animals suffer from a weakness that makes them easy prey—that they are easily toppled because of their stiff, unbending legs. Simple observation should have quickly killed this belief off. Just by spending a few minutes watching elk, moose, or cattle, anyone can see that they bend their legs, lay down to rest or sleep, and that they can easily get up again. Did the same mistaken belief—easily corrected by observation— arise twice, and was it twice perserved by being applied to two identical hunting tall tales? More likely the older story influenced the newer one in which urban tale tellers replaced the elk or moose with a more familiar animal. ![]()