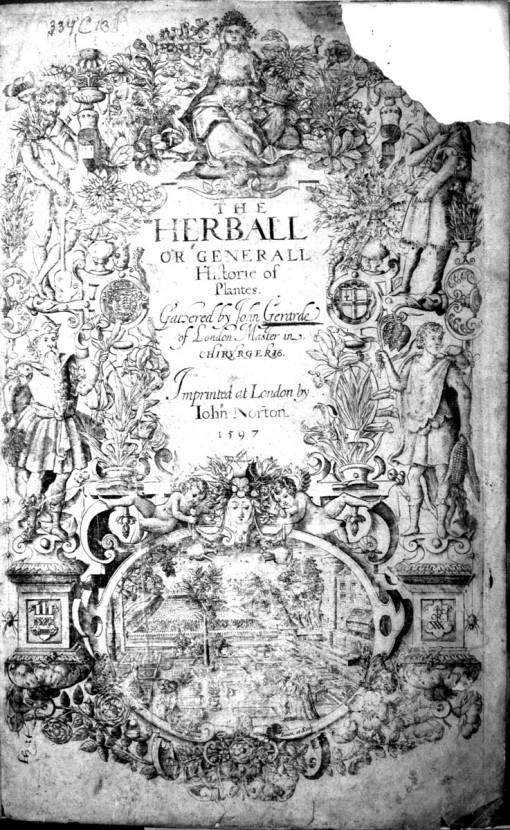

Shakespeare, is that you? Detail from the title page of John Gerard’s Herball

During the past couple of days, media outlets have been running stories claiming that the only authentic portrait of William Shakespeare made during his lifetime has been discovered by botanist and horticulturalist Mark Griffiths. Most of the articles include a quotation from Mark Hedges declaring this to be the “literary discovery of the century.” Is a portrait of a literary figure a literary discovery? I suppose that’s a semantic quibble that doesn’t really matter. Often great literary discoveries are made by scholars who study the relevant literary field, and great discoveries concerning art history are made by art historians. At first glance, a botanist writing about a portrait of Shakespeare would seem to be arguing outside his field of expertise, and Shakespeare tends to attract some peculiar interpretations. But that doesn’t really matter as long as Griffiths provides strong evidence in a peer-reviewed journal like Shakespeare Quarterly, or Shakespeare Survey, or one of several other scholarly journals dedicated to Shakespeare in particular or English literature in general.

Or Country Life, a weekly glossy magazine devoted, according to Wikipedia, to “the pleasures and joys of rural life.” It has featured articles on “Britain’s Best View, The Cream of Counties survey, England’s Favourite Village, Britain’s oldest inhabited dwelling (2003), and Dream Acres imaginary landscape (2009)” (Wikipedia). And, or course, “the literary discovery of the century” (2015). Hmmm. My friend Sharon Hill of Doubtful News often warns her readers about “Science by Press Conference.” That warning can be broadened to include all Scholarship by Media Blitz.

Scholarly Journal versus Glossy Magazine

So what are the subtle clues that Country Life is not a scholarly journal? Well, for starters, I was able to purchase the issue without having to sell any major organs (not a complaint, just an observation). Country Life is published weekly; scholarly journals are generally published much less often—the peer review process takes time. Before I got to any content in Country Life, I flipped (or swiped) through pages and pages of ads featuring elegant homes in gorgeous green vistas. Scholarly journals may have some advertisements for academic publications or conferences, but, for the most part, they are free of commercial advertisements. This lack of advertising is the main reason that individuals need to sell major organs to afford a subscription.

Another difference: before I got to Griffiths’ article in Country Life, I encountered two blurbs telling me in no uncertain terms how important the discovery is and how irrefutable the evidence is. First comes editor Mark Hedges’ “The Literary Discovery of the Century” (103) in which he proudly announces “the astonishing new image of William Shakespeare, the only known and demonstrably authentic” portrait from his lifetime. This discovery “required a rare combination of disparate intellectual disciplines,” and apparently Mark Griffiths was the only man for the job. We are told about Griffiths’ “international reputation” as a horticulturalist, his work as a botanist, and his time studying English as an undergraduate at Oxford:

Crossing the Sciences and the Humanities, his range of interests made him uniquely qualified to investigate a great if misunderstood Elizabethan, the surgeon, botanist and gardener John Gerard. What he didn’t realise as he embarked on this project is that it would also qualify him to discover the greatest Elizabethan of them all. (203)

He adds that, in his 25 years working in magazines, he has “never come across a bigger story.” Yes, it’s even bigger than “Castle Combe: Most Picturesque Village in the Cotswolds?” (okay, I made that up, but it is awfully darned picturesque).

Next up is “I Know Who the Fourth Man Is—It’s Shakespeare,” which features the header “Fellow academics salute the extraordinary significance of Mark Griffiths’s achievement and we show the trail of clues that led to the greatest discovery in literature.” It’s gone from the literary discovery of the century to the greatest discovery in the history of literature. Wow. In 1934, W. F. Oakeshott discovered a manuscript copy of Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur which differed substantially from William Caxton’s printed edition. The great Middle English alliterative poems Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Pearl were almost entirely unknown until Thomas Warton discussed their manuscript (London, BL MS Cotton Nero A x) in 1824. In 1925, Leslie Hotson discovered the coroner’s inquest report on the death of Christopher Marlowe. Meh, whatever.

One of the “fellow academics” is Edward Wilson, described in the article as “Emeritus Fellow of Worcester College, Oxford” and “the former Garden Master at Worcester” (104). He is not a Shakespeare scholar nor an art historian, yet he is said to have “subjected Mark’s findings to rigorous scrutiny” before declaring them “the most important contribution to our knowledge of Shakespeare in generations.” We know he is qualified to do this because he says he is. He tells us that he is “a specialist in medieval literature,” has done “some work in the early Renaissance,” and has had “long experience of manuscripts, iconography, symbols and questions of attribution. I also have a track record in debunking alleged ciphers.” The other academic who enthuses over Griffiths’ work is Sir Brian Harrison, emeritus professor of modern history at Oxford and former editor of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Not a Shakespeare scholar nor an art historian.

Regardless of the qualifications of Griffiths, Wilson, and Harrison, this praise hardly constitutes peer review. Generally in peer-reviewed journals, the reviewers do not know who the author is, and the author does not know who the reviewers are. In this case, Wilson has been directly involved in Griffiths’ work for a long time: “I had watched as his investigation of John Gerard developed and had taken part in it…. I set out methodically to disprove his hypothesis.” (104). In addition, scholarly journals usually don’t depend on fanfare or declarations of legitimacy and importance. They allow authors to make their own case by presenting their well-cited evidence. Griffiths’ article contains no footnotes, endnotes, parenthetical citations, or bibliography.

Griffiths’ Argument

Griffiths had been working on a biography of botanist, herbalist, gardener, and barber-surgeon John Gerard. Gerard is principally known for compiling the massive (nearly 1500 pages) Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes, based on the Latin Herbal by Flemish botanist Rembert Dodoens. Gerard has been accused of plagiarizing a substantial part of the Herball from an incomplete text by an earlier translator who had died and from original work by Matthias de L’Obel. Griffiths claims these accusations are all based on the lies of L’Obel, “a botanical Iago” (Griffiths 123).

Gerard’s Herball, published in 1598 (according to modern reckoning) includes an illustrated title page engraved by William Rogers, the first known native English engraver. The engraving features four male figures. According to Griffiths, most modern commentators identify the figures as “historical, mythical or stereotypical figures,” such as a gardener, a “botanical great from Antiquity…one of the founding fathers of Western medicine” and Apollo (124, 126). Griffiths, however, believes that the figures “were merely playing these roles. They were, in fact, camouflaged portraits of the men who made The Herball happen, and their identities were encrypted in the plants that accompanied them” (126). He identifies the gardener as John Gerard, the botanist as Rembert Dodoens, the statesman/King Solomon (previously identified as “one of the founding fathers of Western medicine”) as Robert Cecil, Lord Burghley, to whom the volume is dedicated. That leaves Shakespeare to play Apollo. All these identifications seem a bit problematic. To a large extent, they rely on the special significance of the plants the figures are holding. Two of the men were botanists who had written massive herbals. I imagine quite a few plants could be said to have significance for them. However, it doesn’t seem too fanciful to consider the possibility that the author, his source, and his patron might appear on the title page. But what about Roman Apollo/Shakespeare?

“Sign of Four” merchant’s mark from title page of Gerard’s Herball

Griffiths begins by discussing the apparent heraldic device underneath the figure. This is a Sign of Four, a merchant’s mark often used by printers. Griffiths found, however, that it was not the mark of any of the printers involved in the publication of Gerard’s book. He concluded that it was a “coded caption…. not a true Sign of Four, but something masquerading as one” (129). Griffiths sees an “E” attached to the 4. I see an “N” and an “L.” He decided the 4 was not a 4, but rather the Latin word “quater” (four times) or an abbreviated form of “quattuor” (four).

The device is asking us to add the E linked to the 4 to either quater or [the abbreviation] quat. The first produces the infinitive of the Latin verb quatio; quatere, meaning “to shake.” The second produces the imperative: quate, “shake!” The rebus is not an arrow, but a spear. The Fourth Man, the modern Apollo, the inheritor of Ovid’s and Virgil’s laurels, is William Shakespeare. (Griffiths 129-30)

I know the Elizabethans liked wordplay, ciphers, and visual puns, but that’s a convoluted explanation of an interpretation of what the symbol (symbols?) is/are. I’ll grudgingly concede the “E,” but I still see an unexplained “N.” I also don’t see a spear. A sailboat, maybe, but shouldn’t a spearhead have equal sides? But wait, there’s more! The letters “O” and “R” appear in the middle of the device on either side of the “spear shaft.” “Or” is the heraldic term for gold. In 1596, Shakespeare’s father was granted a coat of arms. It included a gold shield. At the bottom of the device, Griffiths sees a “W.” So do I. Naturally, he interprets this as “William.” He also sees a Λ, a capital lambda. He notes that in some Signs of Four, this symbol represents the letter “A.” Shakespeare’s mother was named Mary Arden. Her family were members of the gentry, and in 1599 (the year after the publication of the Herball), the Shakespeares requested permission to incorporate the Arden arms in their coat of arms. Griffiths claims that Shakespeare “almost certainly dreamt up this device” (130).

This all seems terribly flimsy. The color gold features on many coats of arms, and we don’t know that the letters here do actually represent the heraldic word for gold. Signs of Four often incorporate letters that make up a name or initials. How do we know this isn’t the case here? The device very noticeably lacks the letter “S.” There is no way to get Shakespeare’s initials out if it, so instead we get “A” for Arden. This reminds me of a common cold reading trick. “I’m getting a ‘W.’ Walter? Wallace? Wayne?” “William! I know a William.” “Yes, William’s here. I’m getting a…lambda.” “Ermm…” “It may be an ‘A.'” “Ermm, no his last name is Sh…” “Well, think about it; it will come to you.” “Wait, his mother’s maiden name was Arden!” Griffiths seems to be making connections that may not exist, and his interpretation is certainly not the only one possible.

Griffiths’ other evidence is based on the plants the figure is holding. In one hand he holds a flower of the Fritillaria meleagris or snake’s head fritillary. In the poem Venus and Adonis, Shakespeare departs from classical sources which identify the anemone as the flower which Venus caused to spring from Adonis’s blood. Shakespeare used the snake’s head fritillary. You may be wondering how he managed to make that scan. He didn’t: “A purple flower sprung up, chequered with white, / Resembling well his pale cheeks, and the blood / Which in round drops upon their whiteness stood” (Venus and Adonis ll. 1168-1170). This fits the snake’s head fritillary, and Griffiths argues that Gerard was its primary champion in England. But why should it be particularly associated with Shakespeare? He mentioned lots of plants. Griffiths’ answer involves complicated biographical information for which there is no evidence. According to Griffiths, Shakespeare was working for Burghley as a propagandist. Venus and Adonis was written to convince Burghley’s ward, Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton (to whom the poem is dedicated) to marry Burghley’s granddaughter Elizabeth Vere, daughter of Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford. The theory is convoluted and without evidence, and Griffiths states his opinions as facts: “When Gerard showed him [Shakespeare] a new ‘daffodil’…something clicked” (134). And it still doesn’t explain why this plant, of all plants Shakespeare mentioned, should be particularly associated with Shakespeare.

The “Fourth Man” also holds an ear of sweetcorn or maize, a plant native to the Americas. Why would a Roman hold this? Why would Shakespeare? Well, according to Griffiths, Gerard “mistakenly believed it was the corn of Pliny” (134). Okay, so maybe the Roman is Pliny the Elder, author of Naturalis Historia. That would make some sense. No, because, you see, in Titus Andronicus, Titus’s brother Marcus says, “O, let me teach you how to knit again / This scattered corn into one mutual sheaf, / These broken limbs again into one body” (Titus Andronicus 5.3.69-71). Shakespeare uses the word “corn” a lot. He uses it to mean “grain,” not sweetcorn. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “corn” wasn’t used to mean “maize” until 1608. Shakespeare has no association with maize. Griffiths also identifies two flowers on the vase near the Roman figure. His attempts to identify them with Shakespeare are no more convincing.

Even if this evidence weren’t astonishingly weak, why on earth would Shakespeare appear on the title page of someone else’s work? He didn’t appear on the title pages of any of his own works during his lifetime. Griffiths argues, without evidence, that Shakespeare helped Gerard with Latin and Greek. Although Ben Jonson famously said that Shakespeare had “small Latin and less Greek” (“To the memory of my beloued, The AVTHOR Mr. William Shakespeare And what he hath left vs” from Shakespeare’s First Folio, 1623), he was perfectly competent in Latin. He probably was much less well-versed in Greek. Regardless, there were many Elizabethans who knew Latin and Greek, so why Shakespeare? Part of it has to do with Shakespeare’s alleged work for Gerard’s patron Burghley. In addition, Griffiths believes Shakespeare helped Gerard with verse translations:

Working closely with him [Gerard], Shakespeare moulded the results [of Gerard’s attempts at translation] into verse piecemeal between 1591 and 1597…. Shakespeare may also have sprinkled magic dust over Gerard’s prefatory matter—it has characteristics of his style and thinking. (132)

He does not provide evidence of Shakespeare’s hand in the Herball and he is not a textual scholar. Aside from one brief translation of Catullus (“With hande of thine / Shake Torch of Pine,” quoted on p. 130), he doesn’t even quote any examples of Shakespeare’s poetic influence on the Herball, although he assures us that “many are longer and more beautiful” (132).

But Griffiths isn’t done with textual scholarship yet. Based on a third flower in the vase, which he identifies as Gladiolus italicus, Griffiths attributes a short comic play performed for the queen at Burghley’s home Theobalds House to Shakespeare’s. Griffiths notes that “No scholar had suggested it was Shakespeare’s work. After subjecting it to all kinds of analysis, however, I believe it is his; likewise The Hermit’s Speech, a long verse address that was delivered to the Queen on her arrival at Theobalds on May 10, 1591″ (135).

Over the years, almost every unattributed scrap of Elizabethan or Jacobean verse (and some works attributed to other authors) has been foisted onto Shakespeare by someone. Very few of these attributions have survived the scrutiny of Shakespeare scholars. An engraving of a plant is not a good substitute for rigorous textual analysis.

Griffiths will present his full argument in his book The Fourth Man, which will be published next year. If his Country Life article is any indication of the book’s reliability, I think Shakespeare scholars will be able to survive the anticipation in relative comfort.

References

- Griffiths, Mark. “Shakespeare: Cracking the Code.” Country Life 20 May 2015. 120-138.

- Hedges, Mark. “The Literary Discovery of the Century.” Country Life 20 May 2015: 103.

- “I Know Who the Fourth Man Is—It’s Shakespeare.” Country Life 20 May 2014: 104.

- All quotations from Shakespeare are from The Norton Shakespeare. Gen. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt. New York: Norton, 1997.

- All images are from the title page of Gerard’s Herball, available through GNU Free Document License. Source www.BioLib.de

The story gets even more risible. The May 27 issue of Country Life tops its previous issue with a lead story, “A Country Controversy,” that it touts on its cover as “New Shakespeare play revevealed.” In this latest article, the estimable Shakespeare scholar/botanist attibutes a very short play, staged in May 1591 for Elizabeth I at the country home of Sir William Cecil, to –you guessed it — Shakespeare. Scholars had for four centuries failed to identify its author, but Mr Griffiths’ proximity to weeds may have boosted his powers of inference.

What will next week’s issue bring?

Jeffrey Herrmann

London

The play was probably written by George Peele (1556-1596) , because it has already been determined that the surviving manuscript is mostly written in his handwriting. Next week’s issue? Real estate, dogs, gardens, and truly beautiful photography. Along with sighs of relief.

Well, a week later it’s all over but the – well, it’s all over. Mr. Griffiths discovered to his great alarm that the only people truly delighted by his findings were Oxfordians, who believed him on the basis that they thought the image looked like Edward de Vere. Then they discovered Mr. Griffiths didn’t much care for them. But they will still claim his findings for the home team.

This has been a cautionary tale. A writer has to know there are limits to what he or she can do. If someone is going to research a topic outside of one’s own field of knowledge, then that person should go to people who work in the field, not people who are as limited as the writer is. Any research into Renaissance literature is littered with the equivalent of the mythic phrase that beyond a certain point “there be dragons.” Few endeavors are more full of cautions than looking into the lives and works of Elizabethan London playwrights, if for no other reason than London burned down in 1666. A few days ago a woman was horrified that I could even think that Griffiths might be wrong, that she knew enough to know he was on the right track! I asked her to answer one simple question: how many plays did Shakespeare write? She never replied. The answer is simple as well – we don’t know how many plays he wrote. What we know about Shakespeare is more than we know of any other English writer of the time, and it’s still not much. Any real discovery of a portrait would be suspect (all proposed portraits of him are argued) and it’s taking centuries for new work to be analyzed and accepted or refused. Shakespeare research is not a job for a man used to having everything already labelled in Latin and several languages, certain steadfast images of flowers and herbs and other plants that all show a viewer what they are and where they came from, because, from ancient times botanists have cared to study and record them. William Shakespeare was a very private man and belonged to a people that generally did not record personal comings and goings. No one will ever find a letter that states “oh and by the way I finished Hamlet today.” And there will be no snapshots. Especially of WS dressed in a toga and laurel wreath.

Time to let this go. I hope Mark Griffiths will let go of the Shakespeare and go back to working on a life of Gerard. That book I would buy. For though this wasn’t a wise way to gain attention, Mr. Griffiths is an excellent writer in his field. That field is full of lovely words and beautiful flowers.

I agree the ‘evidence’ presented smacks of the same kind of convoluted schemes by which some people are determined to prove Shakespeare’s plays were written by just about anyone except Shakespeare. (This is not the venue to delve into the obsession with Shakespeare above all other poets. But I am a Cassius of literature myself and ask aggrievedly why it is the wide walls of art, like Rome’s, must now encompass just one man.) But given the popularity of Shakespeare’s work in his own time, it’s quite possible that a clever artist would sneak in a likeness. It’s clearly not proved to be Shakespeare, particularly not based on the DaVinci Code-type evidence presented in Country life – but it’s close enough not to rule it out.