Actor Kirk Cameron. Image by Gage Skidmore, via Wikimedia Commons. Used under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Kirk Cameron, former child actor and current fundamentalist Christian and Young Earth Creationist, is promoting a new film, Kirk Cameron’s Saving Christmas. Based on the trailer, it seems that Kirk’s brother-in-law, Christian, played by the film’s director and co-writer Darren Doane, isn’t enjoying the Christmas season: it’s too commercial and has pagan roots. It’s just not Christian enough for Christian. Luckily Kirk is there to show Christian that every element of Christmas is directly related to Jesus and Christianity. The proselytizing and forced merriment make me want to slap a reindeer.

But Christmas isn’t the only holiday Cameron wants to save. He also has big plans for Halloween. In an interview with the Christian Post, Cameron explains that Christians shouldn’t hesitate to celebrate Halloween because it is, like Christmas, an entirely Christian holiday:

The real origins have a lot to do with All Saints Day and All Hallows Eve. If you go back to old church calendars, especially Catholic calendars, they recognize the holiday All Saints Day, with All Hallows Eve the day before, when they would remember the dead. That’s all tied in to Halloween.

Most of this statement is mostly true, although it’s simplistic and tautological: Halloween has “a lot to do” with All Hallows’ Eve, and All Hallows’ Eve is the day before All Saints’ Day. Well, yeah. Halloween and All Hallows’ Eve are the same thing, so, yes, one has a lot to do with the other, and “hallow” derives from the Old English halga, which means a holy person or saint, so All Hallows’ Eve must be the day before All Saints’ Day. It’s odd that Cameron considers this illuminating information, but he is correct.

After explaining the trivially obvious, Cameron offers a Christian interpretation of Halloween costumes:

Early on, Christians would dress up in costumes as the devil, ghosts, goblins and witches precisely to make the point that those things were defeated and overthrown by the resurrected Christ. The costumes poke fun at the fact that the devil and other evils were publicly humiliated by Christ at his resurrection.

He’s on shakier historical ground here, and he uses an extremely unfortunate analogy:

When you go out on Halloween and you see all people in costumes and see someone in a great big bobble head Obama costume with great big ears and an Obama face, are they honoring him or poking fun? They are poking fun at him.

A charitable interpretation of this comment is that he is using the analogy to show that Halloween costumes are often cartoonish exaggerations rather then reverent representations. However, it does sound as if he is equating the President of the United States with “the devil and other evils [that] were publicly humiliated by Christ at his resurrection.”

While Cameron seems to place Obama with the devil and witches, he won’t allow them to own Halloween:

Over time you get some pagans who want to go this is our day, high holy day of Satanic church, that this is all about death, but Christians have always known since the first century that death was defeated, that the grave was overwhelmed, that ghosts, goblins and devils are foolish has-beens who used to be in power but not anymore. That’s the perspective that Christians should have.

Unsurprisingly, Cameron’s comments have drawn criticism from such outlets as Raw Story, Jezebel, Wonkette, Politicus USA, the Huffington Post, and even a Washington Post blog. The authors all point out that Halloween is not as Christian as Cameron would have us believe. Instead, its roots go back to the pagan Celtic festival Samhain. Raw Story’s David Edwards says,

Historians universally recognize Halloween’s origins as dating back to the Celtic festival of Samhain, in which the ghosts of the dead were said to return to earth for one night.

To support this contention, he links to the History Channel’s completely unsourced History of Halloween. The Huffington Post’s Ed Mazza agrees:

[A]ccording to anthropologists, the true origins of Halloween go back about 2,000 thousand years to the Celtic holiday of Samhain, which celebrated the end of the harvest season.

He links to another article on the Huffington Post, which links to the History Channel’s History of Halloween.

So are the roots of Halloween pagan rather than Christian? Does it derive from Samhain? Samhain and other pagan festivals celebrating the harvest and the transition from summer to winter very likely did influence modern celebrations of Halloween to some degree, but the articles criticizing Cameron all say that Samhain is the true origin of Halloween and suggest that the Christian church usurped and suppressed the pagan festival.

![Early 20th-century Irish jack-o-lantern made from a turnip. Rannpháirtí anaithnid Wikimedia Commons [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], from Wikimedia Commons](https://www.skeptic.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/466px-Traditional_Irish_halloween_Jack-o-lantern-200x257.jpg)

Early 20th-century Irish jack-o-lantern made from a turnip. Image by Rannpháirtí anaithnid, via Wikimedia Commons. Used under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

There are other problems with some of the claims made about Samhain. First, how old is Samhain? Mazza says it’s 2000 years old. Wonkette’s Doktor Zoom uses sarcasm to indicate it is very ancient, older than All Saints’ Day and Christianity itself:

Old church calendars! And All Saints’ Day has been celebrated on Nov. 1 from the earliest days of Christianity, going back all the way to… um, the 8th Century. And there is absolutely no connection between that holiday and the Celtic festival of Samhain, which predates Christianity, but probably not really because historians always lie about Jesus to make Him look bad.

The earliest references to Samhain come from the 10th-century Tochmarc Emire, 200 years after the date Zoom attributes to the commemoration of All Saints’ Day on November 1. Of course Samhain is older than that, probably much older, but we don’t know how old, and our information comes from comparatively late sources. And those sources were written by Christians.

The idea that November 1 was chosen for All Saints’ Day because it coincided with Samhain is also problematic but accepted as fact by Cameron’s critics. As Jezebel’s Kelly Faircloth says:

You think they plunked All Saints Day down right next to Samhain because Jesus died for your pumpkin spice lattes? Whatever.

All Saints’ Day was celebrated on different days in different parts of the western Christian world. By the mid-fourth century, Christians had begun honoring all martyrs on a special day. In the Mediterranean, the celebration was in May. Churches in England, Germany, and the Frankish empire, however, were celebrating the feast on November 1 by 800 (Hutton 364). Louis the Pious, at the urging of Pope Gregory IV, formally confirmed November 1 as the official All Saints’ Day in 835. If the date is linked to Samhain, why did its celebration on that day spring from the Germanic world? It could be argued that Anglo-Saxon England was influenced by its Celtic neighbors and that the tradition then spread from England to other Germanic areas. However, Hutton notes that “the Felire of Oengus and the Martyrology of Tallaght prove that the early medieval churches [in Ireland] celebrated the feast of All Saints upon 20 April.” He concludes that “both ‘Celtic’ Europe and Rome followed a Germanic idea” (364).

How was Samhain celebrated? That question may be unanswerable, since our sources are relatively late and provide limited information, but many of the claims made about Samhain are not supported by the earliest texts. According to medieval Irish works, Samhain was a festival that marked the transition from summer to winter, and it was a time of feasting and social gatherings. Many literary adventures began on Samhain, though this may be simply because it was a time when people were gathered together. Some scholars have argued that Samhain had a particular connection to the supernatural because many stories set during Samhain involve a character encountering or being attacked by supernatural beings. While Hutton admits that this interpretation may be correct, the “point cannot be proved from the tales themselves; it could just be that several narratives are started, set, or concluded at this feast because it represented an ideal context, being a major gathering of royalty and warriors with time on their hands” (362). He compares the Samhain stories to Arthurian tales that often begin at a feast celebrating Christmas or Pentecost and which often involve supernatural elements, such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Although Hutton agrees that Samhain likely had a pagan religious element, “none of the tales portray any,” although they are much more informative about religious observances during Beltane, the festival commemorating the beginning of summer (361). He suspects that “the rites of Samhain do not feature in medieval Irish literature simply because by the time that it was written, centuries after Christianization, the authors did not know what they had been” (361). It could be argued that the information had been lost because of intentional suppression by the church, but that would be a rather circular argument, as well as an argument from ignorance.

Such an argument was made, however, by Sir James Frazer. According to Hutton, Frazer took Rhys’s idea that Samhain marked the New Year and used it as the basis for his own proposition:

…Samhain had been the pagan Celtic feast of the dead. He reached this belief by a simple process of arguing back from a fact, that 1 and 2 November had been dedicated to that purpose by the medieval Christian Church, from which it could be surmised that this had been a Christianization of a pre-existing festival. He admitted, by implication, that there was in fact no actual record of such a festival, but inferred the former existence of one from a number of different propositions: that the Church had taken over other pagan holy days, that “many” cultures have annual ceremonies to honour their dead, “commonly” at the opening of the year, and that (of course) 1 November had been the Celtic New Year. (Hutton 363)

In other words, he had no evidence to support his claim. There is no clear association between Samhain and the dead. There is, however, a very clear association between the Christian commemoration of Hallowtide. I admit that I don’t know a great deal about Celtic mythology, but when researching and writing my dissertation, I read a lot about early Christian and medieval attitudes towards death, the dead, and the afterlife. Christians have a long history of care and concern for the dead. This is not a uniquely Christian trait, of course. Rather, it is something that seems common to humans.

Early Christians commemorated the deaths of martyrs on their individual saints’ days. As the number of martyrs grew, they began to put aside a day to commemorate all of them. This, as we have seen, was the origin of All Saints’ Day. It commemorated all saints “known and unknown,” including those not officially recognized by the church. Meanwhile, people prayed for the non-saintly dead. Religious communities kept lists of their dead members and said masses for them:

…Masses with Mementos of the Dead, that is, Masses for the Dead, were said continuously in a great many chapels or monastery churches after the ninth century. At Cluny, these Masses went on day and night…. It seems that various localities set aside one day a year for all the dead, that is, for those who, unlike clergymen and monks, were not assured of the help of their brothers–the forgotten people, the majority of laymen. (Philippe Ariès 159)

As with All Saints’ Day, All Souls’ Day was celebrated at different times in different places. In the 11th century, St. Odilo, abbot of Cluny, established November 2 as the date for the commemoration of All Souls’ Day at his monastery and all its daughter houses. The November observance spread from Cluny to other Benedictine houses and ultimately to the rest of western Christendom. It is no coincidence that it fell on the day after All Saints’ Day:

[All Souls’ Day] could be conveniently linked to the preceding festival, as saints were increasingly seen as intercessors upon behalf of departed souls facing judgment or suffering it. Indeed, by the high Middle Ages both festivals had become primarily a time at which to pray for dead friends or family members…. (Hutton 364)

Both days are intimately connected to the evolution of the concept of Purgatory, although both were celebrated before Purgatory was adopted as official church doctrine. Purgatory allowed people to feel they were giving material aid to dead loved ones by praying for them, requesting the intercession of saints, and paying for masses to be said. This led to abuses: religious houses essentially became factories that produced masses for the dead. The rich hoped that they could save their own souls by leaving massive bequests to pay for masses. Some bankrupted their families doing so (Ariès chap. 4).

As well as producing masses for the dead, monasteries also produced ghost stories. Purgatory gave doctrinal justification to ghost stories—lots of ghost stories. While souls in hell could not return, according to most church authorities, and those in heaven would not, souls in Purgatory could return and had reason to do so. Ghost stories were used for propaganda: the ghosts returned and asked for suffrages and masses.

Because of their association with Purgatory, certain rituals associated with Hallowtide were suppressed during the Protestant Reformation, though some traditions remained, such as begging for soul cakes.

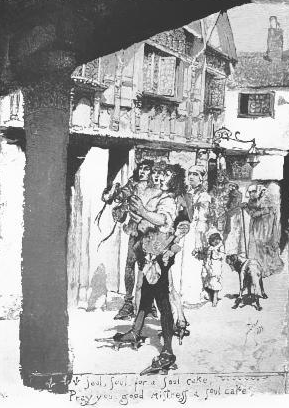

Souling on Halloween. from “St. Nicholas: An Illustrated Magazine for Young Folks”, Scribner & Company, December 1882, p. 93

In discussing the disapproval some fundamentalist Christians express toward Halloween, Hutton notes,

If so many of those traditions appear now to be divorced from Christianity, this is precisely because of the success of earlier reformers in driving them out of the churches and away from clerics. (384)

Halloween does have Christian roots. While it may also have some pagan elements, those are so intertwined with the Christian tradition that it is impossible to disentangle the strands. Kirk Cameron’s notions about Halloween are simplistic, poorly researched, and partly wrong, but those who criticize him by asserting that Halloween is simply a pagan holiday with a superficial Christian veneer are also using simplistic, poorly researched, and partly wrong arguments.

Sources:

Ariès, Philippe. The Hour of Our Death. Tr. Helen Weaver. 1981; New York: Barnes, 2000.

Hutton, Ronald. The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain. Oxford UP, 1996.

Le Goff, Jacques. The Birth of Purgatory. Tr. Arthur Goldhammer. U of Chicago P, 1984.

Schmitt, Jean-Claude. Ghosts in the Middle Ages: The Living and the Dead in Medieval Society. Tr. Teresa Lavender Fagan. U of Chicago P, 1998.

Slap a reindeer? Slap a REINDEER!? I hope Rudolph smacks ya over the head with an empty whiskey bottle!

Very well researched piece.

It would be very nice if we had real evidence of what the pre-Christian people in the UK actually believed but we dont, so it’s rather easy to make unsubstantiated claims. about the origin of this or that tradition.

For me, as a person who believes in and follows a Pagan belief system, the actual origin of a celebration / festival isnt important, its the meaning to the individual that matters. So the Christians can have their All Hallows ‘Eve, I will have Samhain and my next door neighbors can celebrate whatever it is that means they have to dress up in Zombie costumes :)

Was Hal

Summary, since I don’t know how much was posted about usfuelly:I went on a religious retreat, and spent the last day or so thereof broken down in tears, generally shaking, howling and rocking in pain, and otherwise incapacitated. I have been picking up the damn pieces since then.The effect of the epic meltdown was basically that everything in my life built on bullshit and lies fell apart, which included a large amount of my mental coping strategies around my perception of my disabilities, my ability to put up with stress, and… yeah.

i think the Christian layers were layered over the pagan ones intentionally. same reason the spanish missionaries built missions on top of kivas.

in first grade i wore my cute little witches costume to school. a catholic school. i was sent to the principals’s office. i was forbidden to parade with the kids for the costume contest.my mother was called to come pick up my costume and never, ever let me dress as a witch again.

the boy and girl who won the costume contest were dressed as a priest and a nun, respectively.

that is when i learned the game was rigged.

pagans have more fun on halloween. end of story.

Interesting article and comments. Very useful for my research on Halloween and Christianity.

And it might surprise you Americans (United Statesmen?) to know that in Australia, Halloween was never ‘celerbrated’ and most people knew little about it at all, unless they got the church version.

Only in the last few years have retail outlets been pushing “Halloween”. About the same times as when US companies bought out our major biscuit manufacturers and started calling biscuits ‘cookies’ :-(

Because of course real “cookies” are dry little cakes (from the Dutch ‘koekje’ meaning little cake”.

And ‘biscuits’ are crisp because they are ‘twice cooked”.

Very best of luck with the therapist.Putting thgnis right, is, in a bunch of senses, impossible. We can never be who we would have been if it hadn’t happened.What I find more useful is to look at it the way emergency responders are supposed to look at the scene — what’s the worst thing? Ok, make that stop being the worst thing — not fixed, not solved, not not-a-problem-anymore, just not the worst thing. Ok, what’s the worst thing _now_?And you iterate, until the worst thing stops being “house on fire” or “scattered body parts” and starts being “oh, crud, I haven’t done the paperwork yet”. It has the great advantage of not pretending that you can get the people out of the house, and treated for smoke inhalation, and burns, and washed, and fed, and their insurance claims filed, and _then_ deal with, oh, hey, house on fire! which a whole lot of “solve the key problem” patterns seem to do.It is a wretched thing to be going through, but the appearance of repressed pain probably means it’s the worst thing now, which means there’s been progress somewhere else.Eventually progress stops meaning yet more stored pain.

Of course, Christianity has ‘pagan origins’.

It derives from Judaism, which derives from the ancient Assyrian religions with supposedly a bit of Egyptian religions thrown in, and Mithraism which was Roman religion related to Zoroastrianism.

One thing does need to be considered: all societies that come into power alter those that they have conquered and traded with. The Celtics ranged all the way to the Alps, deep into France, as far east as Germany and they built wooden roads all over Europe. The Celts “traded” for Roman wine, Indian artwork, and even Middle Eastern spices. The Romans took over a lot of the Celtic areas because they had gold and correct “Lunar” calendars that allowed them to keep better track of harvests and planting.

Pagans (as well as Christians) throughout history have overthrown every society they have come across. Holidays, languages, clothing, folklore, and even foods and diseases have all been melded.

Claiming a perfect source for a holiday is a bit selfish and ignorant.

I enjoy Halloween because of the various possibilities of its source. I like Winter Solstice because of the huuuuge amount of tales and stories that come with it!

Fundamentalists of ANY religion or practice are a bit annoying.

We have lived long enough and traveled far and wide enough that even our base genetics have melded a bit. ;-)

Blessed be!

Kat

Julian Halloween has been a big deal in Ireland for a very long time and it is my belief it was the Irish that brought the tradition over to the US with emigration around the time of The Great Famine where it has been embellished and evolved. The British have their own similar holiday in November on Guy Fawkes Day which is why Halloween has never been as big a deal there. But here in Ireland we celebrated Halloween with trick or treating, bonfires, and party games in my childhood as we do now fifty years later except like everything else its all gotten grander over the years.

Hutton also suggests that the Irish spread Halloween–or certain aspects of its celebration–to the US.

One thing to be aware of is that there is a lag time between a book being aliavable for review and the date that review posts. I review for Dark Divas and Jessewave (crossposted to my own site and to Goodreads), and can tell you that there can be 2-4 weeks until posting, and that it’s not necessarily the newest books out that get reviewed. You might want to consider Amber Allure as your fourth publisher in the rotation: they tend to some high quality reads.

You are so, so right! That’s why I list the September books in October (and November) and I’ll be listing the October books in November and early December. And I will go back and upadte the lists.And thanks for the suggestion about Amber Allure! I’ve got a list of publishers to look at early this week. I may pick a couple to make a list of 20ish books.p.s. I love your reviews.

There’s another aspect to the origins of Halloween that seems relevant to me. If you look at holidays in the US from a wide perspective (and this is very general) there two things that seem generally true. One is that the holidays, like they have since ancient cultures take place at 4 major times of the year, the solstices and equinoxes. The second is the US seems to largely follow Germanic traditions in regard to holidays. There are a lot of exceptions in the details but again this is just wide generalization. One belief that extends back through the Indo-European origins in the Germanic traditions, is the Wild Hunt. There are lots of variations of this concept through Europe and extending into India. In the Germanic tradition, Woden and later Odin in Scandinavia led the gods on a hunt every fall that extended through the winter months and basically anything that crossed their path was prey. The variations that evolved largely imagine that the hunt as being carried out by ghosts, spirits and fairies. In the oldest warrior traditions, the warrior/hunters were also associated with wolves. This is an over-simplification of the concept to just take a wider view. Some of this concept may have even fed into some of the traditions at Christmas.

In the modern view of Halloween in the US and in Pagan traditions, Halloween is seen as a time when the separation between the living world and the afterlife is weak and entities from the other side can slip through and cause chaos. This sounds like a partial description of the wild hunt.

Modern Halloween is a likely confluence of many factors; traditions, half-remembered myths, politics and commercialism. The Christian church has a great survival mechanism in the fact it has always adapted to existing traditions and celebrations and Halloween is no exception. Regardless we would be celebrating something around the Vernal Equinox.

And I was just wornenidg about that too!

In the UK Halloween is viewed totally as a “Modern American” import. Arriving here as a child in the late 1970s I was horrified to find that no-one “Trick & Treated”, no decorations, no pumpkins (or Turnip Jack o lanterns) and few had even heard of Halloween

Things are a lot better now – supermarkets have pumpkins and my kids go Trick & Treating – but still very much a minority thing – less than 10% of houses accept callers (only knock if the house is decorated).

There is quite a lot of opposition to Halloween – but only because it’s deemed to new, not traditional & foreign (American).

I would be interested to know how much it’s cellebrated in neighbouring Ireland. I find it difficult to believe, given the huge Irish population in the UK that it didn’t crossover.

I suspect Halloween is more modern & American than is claimed.

One of the things this article highlights is that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. There were Christian, Greco-Roman and barbarian components that went into the mix of cultures out of which came Western Civilization. Yet, Western Civilization itself, including its major and minor holidays, was and is something new and different from its antecedents. Thus, as the article correctly explains, the minor holiday of Halloween combines Christian and pagan elements, and is also influenced by regional variations to produce something new and unique to our culture. I should also add that much of the tradition of giving children, specifically, candy and other treats could well be heavily influenced by the twentieth (and now twenty-first) century, American, secular interpretation of Halloween.

This was very interesting and I was delighted that it didn’t have that snooty tone that many scholars take. Too often, academic folks take far too much delight in “giving F’s” to lay persons. It is frequently manifest as critiquing the science in science fiction or the legal aspects of court-room dramas. In fact, the authors of many of those critiqued articles were guilty of this snobbery (and thus made themselves a worthy target for the gleaming light of scholarship).

I applaud Ms Siebert for her restraint – it must have been hard not to get snooty with some of those snooty (and erroneous) responses to Kirk’s Christian feel-good tonic. She set a fine example for all of us – double-check your facts before gleefully telling someone else that they’re wrong!

My doctoral research confirms Eve’s observations.

Bravo! You are better than everybody now that you have proven both sides are wrong and you are the beacon of reason that stands above them. You win the award for being most skeptical. Nobody knows anything and everything is made up.

That my friend is the truth.

Dr. Stella you have made an enormous dincfreefe in my life and I give JESUS praise for the HOLY GHOST FIRE that I an now experiencing. May ALMIGHTY GOD Blessthe works of your hands to be able to reach out to theSix Billion Souls here in the world. Lots of LOVE from the BAHAMAS.

That’s the way most of these types of discussions go… (on and on and on?) and end.

I have no spoons for coenhret comment, but hope that all goes well.Also I’m not sure I know what happened at Samhain, but I’ll go to look now to see if it’s public or on a filter I can read, and assume it’s none of my business if not :/