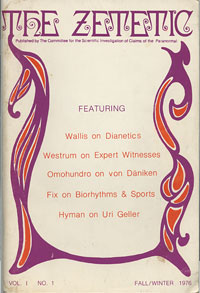

The 1976 founding issue of The Zetetic, now known as the Skeptical Inquirer.

In May 1976, the first major modern skeptical organization in the United States was formed at a special meeting of the American Humanist Association (AHA). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP, now known as the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, or CSI) was established under the joint leadership of co-chairmen Paul Kurtz, a philosopher at the State University of New York at Buffalo and editor of AHA’s The Humanist magazine, and Marcello Truzzi, a sociologist at Eastern Michigan University. The two co-chairmen had different ideas about what the goals of the organization should be—Paul Kurtz wanted to publish a popular magazine and respond to a “rising tide of irrationality” exemplified by a high rate of belief in astrology, while Truzzi wanted to publish an academic journal that was open to both proponents and critics of paranormal claims.

Kurtz’s view won out—Truzzi resigned as co-chairman and editor of CSICOP’s magazine, The Zetetic, on August 10, 1977, and then from the organization completely on October 29 of the same year, writing that he was resigning

because I find that my views towards both what constitutes a truly scientific attitude toward such [paranormal] claims and what should be a democratic structure within our Committee are not being reflected in the statements of the Chairman, Paul Kurtz, or the actions of the Executive Council. Since Fellows of the Committee not on the Executive Council are given no vote and are viewed as merely “advisory,” I see no way in which my original goals for our Committee can be met. These goals included objective inquiry prior to judgment and clear separation between the policies of the Committee and those of the American Humanist Association and The Humanist magazine. I have come to believe that Paul Kurtz does not completely share those goals.

Under Kurtz’s leadership, the roster of CSICOP Fellows and Scientific and Technical Consultants grew to include many major scientific figures from around the world; the magazine, renamed Skeptical Inquirer, grew in circulation; and the organization was regularly called upon by the mass media to provide a critical counterpoint to stories that involved paranormal or supernatural claims.

Truzzi formed a competing organization, the Center for Scientific Anomalies Research (CSAR), and published a journal called the Zetetic Scholar, which published thirteen issues between 1978 and 1987. Truzzi also periodically commented in the media, sometimes to express criticism of CSICOP and its more prominent members. CSAR was essentially a one-man show, and ceased to exist after Truzzi died in 2003. Kurtz’s organization, by contrast, has grown substantially and has continued to thrive after his death in 2012.

But what were CSICOP’s original goals, and has the organization successfully met them? What are the goals of the other skeptical organizations that have been formed in the U.S. and around the world since (and in a few cases, before) CSICOP, and are they being achieved? Just what is the value and purpose of “organized skepticism” as a movement, as a set of institutions, as a network of people participating in conferences, writing articles and books, recording podcasts and videos, and interacting online? What does it accomplish, what is the broader social context in which it resides, and what is its relation to the institutions, practices, and subject matter of science? Does it do anything that isn’t already done by science, science journalists, science communicators, historians and philosophers of science, social studies of science, science museums, science educators, and just ordinary amateur science-interested people? What can skeptics learn from these other areas? What does it mean to self-identify as a “skeptic”? Where has skepticism gone wrong, and what can we learn from its failures? Are there alternatives to “organized skepticism” that might better achieve all or some of its goals?

These are some of the questions I plan to raise and discuss in my contributions to this blog, written from the perspective of someone who has been involved in some respect with organized skepticism for more than three decades in numerous roles as a consumer, contributor, organizer, and occasionally as a somewhat harsh critic. My academic background is in philosophy; I earned an M.A. but failed to complete a Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Arizona, where I specialized in epistemology and minored in cognitive science. I’ve done more recent graduate work in a Ph.D. program in Human and Social Dimensions of Science and Technology at Arizona State University, which was a wonderful opportunity to take some excellent classes in the social studies of science; science, technology, and the law; religious cults and the law; and history and philosophy of science. But alas, for a second time I decided that I didn’t really want the Ph.D. enough to keep spending time and money on it. I thus am not a credentialed expert at the doctoral level in anything; the nature and value of credentials and expertise and how to identify relevant experts is another topic of interest with respect to skepticism that I plan to discuss in my contributions to this blog.

I also expect to occasionally blog on other topics of interest, including but not limited to creationism, conspiracy theory, hoaxes, Scientology, and forteana.

I am grateful to Daniel Loxton for inviting me to participate in this project. I think he has done much to shed light on some of the questions I ask above in his projects looking at the history of skepticism and asking “Where do we go from here?” (PDF). I hope I can make some complementary contributions to his work.

What is organized skepticism good for, and does it matter?

“I’ll tell you later.”

Good one, Jim! Ya got me!

Looking forward to the follow up articles. I can’t help but raise an eyebrow in derision when I get asked, “Who cares what people think?” or “How can someone’s belief hurt you?” and especially, “I read this article by Dr. [insert quack]…”.

Jim, I really look forward to your blog posts here. You have always been one of the more objective and fair-minded of skeptics; critical but charitable, willing to criticize even fellow skeptics, but always with solid reasoning and documentation. And your philosophical background will be helpful.

Well said!

When I first discovered the skeptic movement in the late ’80’s Jim’s

online collection of skeptical links was an enormously helpful guide and education into the movement. His presence on the skeptical blogs of the time was a model of fairness and rationality. It’s good to see him on Insight.

There were skeptical blogs in the late 80’s?

Jim’s involvement in online skepticism does go back amazingly far. Skeptic ran an article he co-authored on just that topic (“Scientology v. the Internet: Free Speech & Copyright Infringement on the Information Super-Highway” by Jim Lippard and Jeff Jacobsen) way back in 1995 (in Vol. 3, No. 3—see Table of Contents here).

I registered the skeptic.com domain name in 1994, I believe. I put selected articles from Skeptic magazine online for download as text files (via FTP) or as web pages, between 1994-1997. My version of the skeptic.com website was pretty no-frills–articles were lucky to have an image of the magazine cover and perhaps one other graphic image.

My first contribution to the magazine appeared in vol. 2, no. 1, Spring 1993–a book review of Ivan Zabilka’s Scientific Malpractice. I had two other contributions prior to the Scientology article, both about George Jammal’s Noah’s Ark hoax, in vol. 2, no. 3 (“Sun Goes Down in Flames: The Jammal Ark Hoax”) and in vol. 2, no. 4 (“Update on the Ark Hoax”). Vol. 2, no. 3 also featured David Bloomberg’s article on the Ark Hoax. Both my article and David’s are part of the TalkOrigins website.

Before there were blogs, there were mailing lists and there was Usenet. Skeptical mailing lists included the BITNET SKEPTIC mailing list hosted first at York University run by Norm Gall (started around 1984?) and then at Johns Hopkins University when it made the move to the Internet (then run by Taner Edis), the first ARPAnet SKEPTIC mailing list co-founded by Toby Howard and me in 1987, and a few others. There was a FIDOnet echo, there were discussion groups on CompuServe and Prodigy, also started around the same time. On Usenet there was sci.skeptic, alt.paranormal, talk.origins (creation/evolution newgroup), alt.religion.scientology, and so on. The newsgroups typically ended up constructing FAQs (and everyone knows what that means now!), some of which made the migration to web archives (such as http://www.talkorigins.org).

My online collection of skeptical links is still around, but hasn’t been much updated lately, and somewhat less necessary now since the search engine was developed: http://www.discord.org/skeptical/

That link list was developed using software similar to the original Yahoo (Yet Another Hierarchically Officious Oracle).

I’ll probably have to do a post about online skepticism before the World Wide Web.

Looking forward to reading your articles, Jim.