A pediatric neurologist at Boston Children’s Hospital diagnosed my son, Misha, with autism spectrum disorder at age three. At Massachusetts General Hospital, another pediatric neurologist answered my call for a second opinion only to rebuff my hope for a different one. “I did not find him to be very receptive to testing,” the expert sighed. Both neurologists observed that Misha didn’t respond to their request to identify colors, body parts, or animals, that he averted his eyes from theirs, that he pawed their examination table when he didn’t flap his arms. Autism, the doctors said, constituted a lifelong condition. Medical science didn’t understand its causes or cures, and scarcely comprehended the limits of its woes.

How could the neurologists deduce such a bleak judgment from 90 minutes in the bell jar of their examination rooms? If they knew so little about autism, then how could they gavel down a life sentence? I remembered reading somewhere that a properly trained neurologist ought to be able to argue both for and against any single diagnosis in a stepwise process of elimination. I opened the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), leafed to the entry under autism, and plucked out of its basket several inculpating symptoms. Aggrieved, I sought out the Handbook of Differential Diagnosis, a companion volume, and underlined an admonitory passage: “Clinicians typically decide on the diagnosis within the first five minutes of meeting the patient and then spend the rest of the time during their evaluation interpreting (and often misinterpreting) elicited information through this diagnostic bias.” Now what?

As an educated citizen of progressive Cambridge, Massachusetts, I consumed large volumes of such second-hand, semi-digested information. I felt that I should, and believed that I could, develop my own, independent judgment about Misha’s condition. I would do my own research, and I would draw my own conclusions based on what I learned.

These virtues turned out to be constituent features of my error. My skepticism and sense of responsibility blended with my stubbornness as I struggled to evaluate a welter of “holistic” attitudes about medicine and health. Several fixed ideas confronted me. Autism, I read, is neither the psychopathology listed in the DSM nor the organic twist of disease supposed by neurologists. Autism, these alternative sources explained, is one among an epidemic of preventable chronic illnesses that American children contract from toxins in the environment. Holistic therapy, according to another, contains the requisite resources. Vitamin therapy, homeopathy, and antifungal treatment could heal children like Misha of their injuries.

The claim that autism is a treatable, toxin-induced chronic illness is a half-century old. Its history forms a pattern of culture and credulity imprinted on our own time. Today, indeed, as one in every 36 children receive the diagnosis, and as controversies swirl around COVID-19, more people than ever turn to holistic remedies to treat illnesses real and imagined. Homeopathic remedies fly off the shelves at pharmacies, alongside an array of alleged immunity-boosting, anti-inflammatory vitamins and herbal supplements.

Critics view the vogue for holism as the product of an irrational transaction between charlatans and suckers. As I reflect on my experience with Misha in the grassroots of autism agonistes, however, I find the issues don’t divide so tidily. The question isn’t whom to trust or what to believe, but how to make an existential choice between incommensurable propositions.

A family friend introduced me to Mary Coyle, a homeopath at the Real Child Center in New York. Coyle said Misha had likely contracted autism from contaminants in the environment. Was I aware of the epidemic of chronic illnesses afflicting children like him? Some of them, Coyle explained, received diagnoses of asthma, chronic fatigue, or dermatitis. Others were diagnosed with fibromyalgia, Lyme disease, or PANDAS (Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal Infections). Pathogens lying at the nexus between the body and the environment fooled medical specialists at places like Boston Children’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital. Coyle urged me to abandon their dead-end query, “Is your child on the autism spectrum?” To help Misha, I needed to switch the predicate and envisage a different question: “How toxic is your child?”

My kitchen turned into an ersatz pharmacy of unguents, powders, drops, and tablets.

Why not find out? Although I had never heard of homeopathy or Coyle’s sub-specialty of homotoxicology, I believed that with some study I could probably draw the necessary distinction between evidence and interpretation in the test results. Coyle herself had been trained by conventional physicians before seeking out propaedeutic instruction in holistic medicine. Holism sounded nice.

We started out with an “Energetic Assessment.” Measuring Misha’s rates of “galvanic skin response,” Coyle said, would weigh the balance of electrical vibrations conducted through his pores. Toward this end, she deployed an electrodermal screening device that deciphered imbalances in his “meridians,” or “pathways.” Toxic metals, alas, appeared from the results to be obstructing his “flow” of energy.

With Coyle’s theory confirmed, she referred me to Lawrence Caprio to canvass for food and environmental allergens. Caprio, like Coyle, had defected from conventional to alternative medicine. I learned that while attending medical school at the University of Rome he had befriended a homeopath in the Italian countryside and lived “a very natural lifestyle”; the experience led him to pursue naturopathy.

Misha—Caprio now reported—turned out to be “intolerant” of bread, butter, eggplant, oatmeal, peanuts, potatoes, and tomatoes. Misha also displayed a “sensitivity” to bananas, car exhaust, cheese, chlorine, chocolate, cow milk, dust mites, garlic, onions, oranges, soy beans, and strawberries. Caprio flagged “phenolics” such as malvin (in corn sweeteners) and piperin (in nightshade vegetables and animal proteins).

Next, I mailed urine and stool samples to the Great Plains Laboratory in Kansas. The director there, William Shaw, had worked as a researcher in biochemistry, endocrinology, and immunology at the Centers for Disease Control before he quit and set up his own laboratory. Shaw suspected lithium in “the bottled water craze” and fluoridation in the public water supply as just two of the causes of autism. He came to believe that government scientists woefully misunderstood such sources. He compared their dereliction to the Red Cross’s failure to intervene in the Holocaust. Shaw also found toxic levels of yeast flooding Misha’s intestines.

Homeopathy, naturopathy, and renegade biochemistry cast me outside the institutions of science where Misha’s neurologists practiced. But to grasp how these new realms might be objective correlates of Misha’s condition—and how toxins, foods, and yeast might be culprits—I had only to remind myself of the progressive demonology that made the diagnosis seem plausible.

Industrial corporations have been chewing up the land, choking the air, and despoiling the water, I read, turning the whole country into a hazardous materials zone. I’d read Silent Spring, in which ecologist Rachel Carson claimed that our bodies weren’t shields, but permeable organisms that absorbed particulates. I’d heard Ralph Nader liken air and water pollution to “domestic chemical and biological warfare.” I’d finished Bill McKibben’s The End of Nature with the requisite dread. Listening to progressive news media about “forever chemicals” evoked moods that swung between indignation and paranoia. I paid for eco-friendly cribs, de-leaded the windows in our apartment, and tried to shop organic.

As Coyle, Caprio, and Shaw whispered in my ear, though, my imagination boggled with an even greater catalogue of possible pathogens. Our food contained more pesticides, hormones, and insecticides than I had suspected. Our air is filled with methanol and carbon monoxide. Chlorine, herbicides, and parasites degraded our tap water. Mold festered in our walls, floors, and ceilings. Formaldehyde lurked in our furniture. Heavy metals hid in our lotions, shampoos, and antiperspirants. Synthetic chemical compounds—polychlorinated biphenyls, phthalates, bisphenol A, polybrominated diphenyl ethers—seeped into our toys, diapers, bottles, soaps, and appliances. Even our Wi-Fi, cell phones, refrigerator, light bulbs, and microwave oven emitted radiation through electromagnetic fields.

Had the dystopia of the contemporary world poisoned my son? Coyle, Caprio, and Shaw not only defined autism as a preventable, “biomedical” illness, they traced the mechanism of harm to his pediatrician’s office.

Misha had received three-in-one vaccines against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTP) and measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) according to the recommended schedule. The holistic experts now told me that these vaccines contain dangerous metals, including mercury and aluminum. The vaccines, I read, could have spread from Misha’s arm to his gut and persisted long enough to perforate an intestinal wall. Mercury, a neurotoxin, could have leaked into his bloodstream and surreptitiously addled his brain. Or his pediatrician could have set off a chain reaction that had the same effect. The antibiotics she gave him for petty infections could have reduced the diversity of natural flora that controlled yeast in his gastrointestinal tract. An overabundance of yeast could have generated enzymes that perforated his intestines even if live-virus vaccines had not done so directly.

Either way, undigested food molecules such as gluten (in wheat) and casein (in dairy) could have joined forces with environmental toxins and heavy metals and attached to Misha’s opiate receptors, disrupting his neurotransmitters and triggering allergic reactions. The ballooning inflammation would have thwarted his immune responses. If so, then his “toxic load” could be starving his cells of nutrients. Escalating levels of “oxidative stress” could be congesting his metabolism. No wonder he lacked muscle tone, coordination, and balance!

How could I dismiss their diagnosis of “autism enterocolitis,” AKA “leaky gut?” My liberal education prided open-mindedness, after all. In 1998, a midlevel British lab researcher named Andrew Wakefield published a study warranting the diagnosis in The Lancet, one of the world’s most prestigious medical journals. Wakefield’s paper, it turned out, “entered his profession’s annals of shame as among the most unethical, dishonest, and damaging medical research to be unmasked in living memory,” according to Brian Deer’s The Doctor Who Fooled the World.

In the meantime, both liberal and conservative politicians echoed the implications of Wakefield’s hoax. “The science right now is inconclusive,” Barack Obama said in 2008. Thousands of media outlets around the world reported a controversy between two legitimate sides. “Fears raised over preservatives in vaccines,” a front-page headline in the Boston Globe announced. Wakefield appeared on television with articulate parents by his side. “You have to listen to the story the parents tell,” he said on CBS’s 60 Minutes. Reputable television programs did just that. ABC’s Nightline, Good Morning America, and 20/20, NBC’s Dateline, and The Oprah Winfrey Show broadcast the gravamen of the indictment out of the mouths of well-educated parents.

The accusation against antibiotics resonated with definite misgivings that I held over the dispensations of American medicine. Doctors in the United States order more excessive diagnostic tests, perform more needless caesarean sections, and prescribe more superfluous antibiotics than their counterparts around the world. A prepossessing dependence on technology encourages American medicine to treat symptoms rather than people. From this indubitable truth, Coyle, Caprio, and Shaw drew an uncommon inference that aggressive medical care had sabotaged Misha’s birthright immunity.

Misha, so endowed, could have repaired the damage done, no matter whether vaccines or antibiotics had upset his “primary pathways.” His body would have availed “secondary pathways” such as his skin and mucous membrane. Coyle said his innate capacity for adaptation had been telegraphing itself in his fevers, his eczema, his ear infections, even his runny noses. Yet his pediatrician had stood blind before the hidden meaning of these irruptions. Reaching into her chamber of magic bullets, she prescribed steroid creams for his eczema, acetaminophen for his headaches, amoxicillin for his ear and sinus infections, antihistamines for his coughs and runny noses, and ibuprofen for his fevers. This “Whac-a-Mole mentality,” Coyle despaired, had plugged his “secondary pathways” as well.

The trio of virtuoso healers would help me sidestep the adulterated dialectic of science and charm Misha’s autism out of its chronic condition.

A vicious cycle set in. Vaccines and/or antibiotics had predisposed Misha’s microbiome to harbor viruses, bacteria, and fungi. Turning toxic, they invaded his cells, tissues, and fluids. The foreign occupation precipitated allergies. The allergies provoked inflammation, which arrested metabolic energy, which led to anemia, which invited recurring infections. His pediatrician perpetuated those with cascading doses of foreign chemicals. “Rather than freak out and take medication and look to suppress,” Coyle counseled, “we should celebrate that the body is working and go and look at the primary pathways and clear out the blockages.” Up to 103 degrees Fahrenheit, “the fever might be a good thing.”

If I could accept that “allopathic” medicine did not stand apart and speak objectively, but instead reflected the sickness of American society, then the trio of virtuoso healers would help me sidestep the adulterated dialectic of science and health. A holistic treatment protocol would charm Misha’s autism out of its chronic condition and turn it into a treatable medical illness. “The body’s infinite wisdom,” Coyle said, “would take care of the rest.” As the protocol purged and flushed his toxins, the fawn of nature would close the holes in his intestines. His allergies would ebb, reducing inflammation, reviving cellular respiration, and reconnecting his neurotransmitters. The realignment of his meridians would reflow his energy. “Once you clear,” Caprio said, “the whole thing just changes dramatically.”

* * *

Autism parents first embraced holistic treatments in the 1960s and 1970s, when emphatic personal testimonials, printed and distributed in underground newsletters, led to the formation of grassroots groups such as Defeat Autism Now! (DAN!) and ushered in the “leaky gut” theory. DAN! grew out of the psychologist Bernard Rimland’s Autism Research Institute. Rimland’s 1964 book Infantile Autism blew up the prevailing, psychogenetic thesis of autism’s origins, which blamed mothers for failing to love their children enough.

The Today Show and The Dick Cavett Show had given psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, the chief exponent of the “refrigerator mothers” thesis, free reign to liken them to concentration camp guards. Rimland’s Infantile Autism refuted that thesis. Letters poured into his Autism Research Institute from grateful parents attesting to the efficacy of the holistic approach: vitamin therapy, detoxification, and elimination dieting. Pharmaceutical companies rolled out new childhood vaccines for measles (1963), mumps (1967), and rubella (1969) and combined the immunizations against pertussis, diphtheria, and tetanus into one injection. Rimland began distributing an annual survey that queried parents about the effects.

Belief in an etiology variously called “leaky gut,” “autism enterocolitis,” or “toxic psychosis” awkwardly amalgamated elements from both ancient and modern medical philosophy. The old idea of disease as a sign of disharmony with nature queued behind the modern concept of infection through the invasion of microorganisms. But no theory of etiology needs to be complete for a treatment to work. “Help the child first,” Rimland urged, “worry later about exactly what it is that’s helping the child.”

Like anti-psychiatry activists, breast cancer patients, and AIDS activists, autism parents confronted physicians with the backlash doctrine of “consumer choice” in specialist medical care. “The parent who reads this book should assume that their family doctor, or even their neurologist or other specialist, may not know nearly as much as they do about autism,” William Shaw wrote in Biological Treatments for Autism.

The first television program to elevate parental intuitions, Vaccine Roulette, aired in 1982 on an NBC affiliate in Washington, DC. The show promoted the vaccine injury theory—and won an Emmy Award. Accelerating rates of the diagnosis over the next decades brought the injury theory from a simmer to a boil. In the 1960s, an average of one out of every 2,500 children received the diagnosis. By the first decade of the 21st century, the prevalence rose to one out of every 88, an increase of over 2,500 percent. Up to three-quarters of autism parents used some form of holistic treatment on their children.

A Congressional hearing in 2012 featured their cause, heaping suspicion on vaccines, speculating on gut flora, and praising the efficacy of vitamins, homeopathy, and elimination dieting. Dennis Kucinich, a Democrat from Ohio and one-time Presidential candidate, expressed outrage over the spectacle of “children all over the country turning up with autism.” Kucinich blamed “neurotoxic chemicals in the environment,” particularly emissions from coal-burning power plants. Like the autism parents in attendance at the hearing, Kucinich did his own research and drew his own conclusions.

“There’s no such thing as ‘conventional’ or ‘alternative’ or ‘complementary’ or ‘integrative’ or ‘holistic’ medicine,” alternative medicine skeptic Paul Offit complained the next year. “There’s only medicine that works and medicine that doesn’t.” Clever and concise, Offit’s polemic nonetheless begged the relevant questions. Who decides what works? Fundamental science is one thing; therapeutic interventions are quite another. “Evidence-based medicine,” introduced in 1991, supplies a template of criteria to translate medical science into clinical medicine. Atop its hierarchy sits the “randomized control trial,” a methodology loaded with social and financial biases. Even when a therapy works incontrovertibly, that fact doesn’t free its applications of ambiguity. Antibiotics work. We’ve known that since the 1930s. But which of their benefits are worth which of their costs?

When does an accumulation of confirmed research equal a consensus of reasonable certainty? In 1992, ABC’s 20/20 exposed a cluster of autism cases in Leominster, Massachusetts. A sunglasses’ manufacturer had long treated the city as a dumping ground for its chemical waste. After the company shuttered, a group of mothers counted 43 autistic children born to parents who had worked at the plant or resided near it. Commenting on the Leominster case, the eminently sane neurologist Oliver Sacks voiced a curious sentiment. “The question of whether autism can be caused by exposure to toxic agents has yet to be fully studied,” Sacks wrote, three years after epidemiologists from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health determined that no unusual cluster of cases had existed in that city in the first place. Who gets to decide the meaning of “fully studied”?

Bernard Rimland and the autism parents in his movement answered the question for themselves. “There are thousands of children who have recovered from autism as a result of the biomedical interventions pioneered by the innovative scientists and physicians in the DAN! movement,” Rimland insisted in the group’s 2005 treatment manual, Autism: Effective Biomedical Treatments.

William Shaw and Mary Coyle, both DAN! clinicians, adapted Rimland’s manual for Misha. Coyle vouched personally for the safety and efficacy of the holistic treatment therein. She swore she used it to “recover” her own son.

Interdicting toxins marked the first step on the “healing journey.” Taking it obliged me to decline Misha’s pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (for pneumonia) and his varicella vaccine (for chickenpox). Meanwhile, I eliminated from our cupboard and refrigerator the foods for which Caprio had proved Misha sensitive and intolerant, and I prepared a course of “optimal dose sub-lingual immunotherapy” to “de-sensitize” him. Coyle drew up a monthly schedule to detoxify him with homeopathic remedies from a manufacturer in Belgium. Shaw itemized vitamins and minerals to supplement Misha’s intake of nutrients, plus probiotics and antifungals to control his yeast and rehabilitate his intestinal tract. My kitchen turned into an ersatz pharmacy of unguents, powders, drops, and tablets.

Every morning, I inserted two tablets of a Chinese herbal supplement, Huang Lian Su, into an apple. This would crank-start his digestion. I added half a capsule of methylfolate into his breakfast. This would juice his metabolism. Ten minutes after he finished breakfast, I stirred Nystatin powder into warm coconut water, drew two ounces into a dropper, irrigated his mouth, and ensured that he abstained from eating or drinking for ten more minutes. Fifteen minutes before his midday snack, I squeezed six drops of a B12 vitamin under his tongue. Every evening, I slipped him two more Huang Lian Su tablets.

An exception in federal law places vitamins, supplements, and homeopathic remedies outside the FDA’s approval process. Only their manufacturers know what these dummy drugs contain.

To fortify his glucose levels, I could elect to give him two vials of raisin water every other hour. To normalize his alkaline levels, I added a quarter-cup of baking soda to his baths. The “de-sensitizing drops,” however, had to be dribbled onto his wrists twice every day. Misha also needed regular, carefully calibrated doses of boron, chromium, folic acid, glutathione, iodine, magnesium, manganese, milk thistle, selenium, vitamins A, C, D, E, and zinc.

Homotoxicology, the core modality, entailed his daily ingestion of homeopathic “drainage remedies” to purge toxins and open pathways. The bottles arrived in the mail. Coyle provided a table of equivalencies, linking particular remedies to organs. This compound for his small intestines; That one for his large intestine; This one for his kidney; and That one for his mucous membrane.

At the same time, homeopathy’s whole-body scope of intervention claimed to relieve a wide range of illnesses. Shaw and his colleagues said the modality could treat autism, plus sensory integration disorder, central auditory processing disorder, speech and language problems, fine motor and gross motor problems, oppositional defiance disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, eating disorders, headaches, eczema, and irritable bowel syndrome. The marketing materials that accompanied Misha’s compounds claimed that they could treat bloating, constipation, cramps, flatulence, nausea, night sweats, and sneezing.

I learned the shorthand rationale as part of my self-education. Homeopaths stake their claim on a manufacturing process that distinguishes their remedies from pharmaceutical medicaments. It’s called “succussion.” A label that reads “4X,” for example, indicates that the original ingredient has been diluted four times by a factor of 10—the manufacturer has succussed it 10,000 times. “12X” indicated that the original ingredient has been succussed one trillion times.

The compounds prescribed for Misha said they contained asparagus, bark, boldo leaf, goldenrod, goldenseal, horsetail, juniper, marigold, milk thistle, parsley, passionflower, Scottish pine root, and other herbs and plants of which I’d never heard. Having been succussed, though, the remedies actually contained no active ingredients. In the bottles remained “the mother tincture,” a special kind of water said to “remember” the original ingredient. The only other ingredient listed on the label was an organic compound that served as a solvent and preservative. Thirty-one percent of some of Misha’s remedies contained ethanol alcohol, a proof as strong as vodka or gin. Coyle instructed me to “gas off the alcohol” on the stove before serving him.

Succussion confused me. Misha’s reaction worried me. He looked a fright. Black circles ringed his eyelids. Yeast blanketed his nostrils and lips. Rashes and red spots appeared all over his body. Pale and lethargic, he oscillated between diarrhea and constipation. He broke out with recurring fevers. He stopped gaining weight. Because he didn’t speak, or reliably communicate in any other manner, I couldn’t understand why his emotions seemed to be running at an unusually high pitch.

Coyle explained that different glands and organs in the body stored specific feelings. The kidneys stored fear. The pancreas stored frustration. The thyroid stored misunderstanding, the liver anger, the lungs grief, the bladder a sense of loss, and so forth. Those emotions poured out as his body excreted toxins. I shouldn’t regard the worsening of his symptoms as a side effect, but rather as a necessary condition of his recovery—“aggravations,” in homeopathy’s parlance. A Table of Homotoxicosis charted the correspondences with the precision and predictability of biochemistry. Nor should I abandon the treatment. To do so would be to “re-toxify” him. I must allow the treatment to fully fledge. I must keep my nerve.

* * *

I lost my nerve. It took 18 months of gnawing doubt and thousands of dollars out the door. Then one day I swept all the vitamins, antigens, probiotics, antifungals, and homeopathic remedies into the trash bin. I restored Misha to a regular diet, caught him up on his vaccines, and demanded (and received) a full refund from Coyle.

I had blundered into a non sequitur. The environment is toxic. Conventional medicine does reflect the sickness of our culture. Yet that doesn’t render holism any better. The supplement industry, I came to understand, has pumped hundreds of millions of dollars into thousands of clinical studies without demonstrating that vitamins, herbal products, or mineral compounds are either safe or effective, much less necessary. The Food & Drug Administration (FDA) neither tests the industry’s marketing claims nor regulates its product standards.

Caprio and Coyle regard Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) as a reproach to modern, Western medicine. TCM, they pointed out, is 5,000 years old. Actually, I learned, Chairman Mao Zedong contrived TCM after 1950 as a means of controlling China’s rural population and burnishing the regime’s reputation abroad. In 1972, during Richard Nixon’s tour of Chinese hospitals, his guides stage-managed a demonstration of TCM’s miracles. American media reported the healing event at face value and launched the holistic health movement stateside. Several years later, the FDA sought to regulate the vitamin and supplement industry. Manufacturers fought back with a marketing campaign centered on “freedom of choice” and convinced Americans to stand up for their right not to know which ingredients may (or may not) be contained in their daily vitamins.

I needed to file a public records request with the Connecticut Department of Public Health to discover that Lawrence Caprio had been censured and fined for improperly labeling medication, for practicing without a license, and for passing himself off as a medical doctor. I also learned that Caprio’s naturopathy license had been suspended for two years after the FDA determined his bogus “sensitivity tests” violated its regulations. Misha, an actual immunologist confirmed, had no food allergies in the first place.

Was my son ever really burdened by toxins? Coyle said the results of the “energetic assessments” revealed that Misha carried quantities of heavy metals. Degrees of dangerousness were measured against a standard range credited to “Dr. Richard L. Cowden.” I sent Misha’s results to Cowden. I stated my belated impression that meaningful ranges for heavy metals don’t exist—we all have traces—and my belief that autism cannot be reversed. “I have reversed advanced autism in many children,” Dr. Cowden snapped. “I saw reversal of more than a dozen cases of full-blown autism, including my own grandson. So I am pretty sure the parents of those dozen+ children would debate you on your IMPRESSION/BELIEF.”

Cowden advised me to repeat Misha’s energetic assessment through the Internet and to place him into an “infrared sauna” to detoxify him. I declined.

Even before Misha’s first energetic assessment, the FDA had accused the device’s manufacturer of making unapproved claims. The FDA had approved it only for measuring “galvanic skin response.” But the company’s marketing materials had crossed over into unapproved diagnostic and predictive territory when they claimed that the “software indicates what is referred to as Biological Preference and Biological Aversion.” The software was recalled. “Dr. Cowden,” I also learned too late, was not the “Board Certified cardiologist and internist” that he advertises. He surrendered his medical license in 2008 after the Texas Board of Medical Examiners twice reprimanded him for endangering his patients. According to the American Board of Internal Medicine, Cowden’s certifications are “inactive.”

The “homotoxicology” that Coyle practiced had sounded to me like a branch of toxicology. But the two fields turn out to have nothing in common. An analysis of clinical trials of homotoxicology established that it is “not a method based on accepted scientific principles or biological plausibility.” Actual toxicologists pass a rigorous examination for their board certifications and adhere to a code of ethics. Homotoxicologists become so simply by declaring themselves homotoxicologists.

As for vitamins, supplements, and homeopathic remedies: an exception in federal law places them outside the FDA’s approval process. Only their manufacturers know what these dummy drugs contain. Last year, after fielding numerous reports of “toxic” reactions, finding “many serious violations” of manufacturing controls, and recording “significant harm” to children, the FDA warned the consuming public.

Homeopathy offers no detectable mechanism of action, nor any reason to believe that “aggravating” the primary symptoms of an illness is necessary to cure it. Water does not “remember,” at least not if the laws of molecular physics hold true. The tinier the dosage, homeopaths insist, the more potent the therapeutic effect the mother tincture will deliver. By this logic, a patient who misses a day might die of an overdose.

As I steered Misha back toward medical science, though, I remembered the gap that holism fills for parents like me. I took him to a “neuro-biologist,” a “neuro-psychologist,” and a “neuro-immunologist.” His “neuro-ophthalmologist” ordered an MRI. His “neuro-radiologist” read the images with algorithms—and pronounced his brain “normal” due to the absence of indications of damage.

That determination proved only the vacuity of scientific materialism. The “biological revolution” that seized psychiatry in the 1980s aspired to network the anatomical, electrical, and chemical functions of the brain. A procession of neuroimaging technologies held out the promise of progress: electroencephalography (EEG); computerized axial tomography (CAT); positron emission tomography (PET); magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS); magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The resulting studies have always fallen pitifully short of a credible evidentiary threshold and have never done anything to expand treatment options. Mainly, neuroimaging has furnished opportunities to market the research industry, a breakthrough culture that has never broken through.

Holism, by contrast, answers prayers in the immaterial world, bidding to restore harmony through an aesthetically elegant fusion of mind, body, and spirit. As Coyle explained on her website: “Homotoxicology utilizes complex homeopathic remedies designed to restore the child’s vital force and balance the biological flow system.”

One part of me still craves holism’s beautiful notions. Another part recognizes in their desiccated spiritualism the return of a repressed pagan unconscious. I can no more believe in goblets of magic water and occult energy than I can conceal my disappointment with “neuro-radiology.”

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 28.4

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

Scientists long ago dispatched the “leaky gut” theory with a series of disproof. Holistic parents, researchers, and clinicians, however, continue to reject what they contend are the false revelations of cold, mechanical instrumentalism. Tylenol, electromagnetic fields, “toxic baby food,” COVID-19 vaccines, HPV inoculation, “geo-engineering,” and genetically modified foods top the current indictment. William Shaw published a paper in 2020 purporting to demonstrate “rapid complete recovery from autism” through antifungal therapy. Mary Coyle attested last year to having healed her son’s chickenpox through “natural” remedies.

Many of the holistic advocacy organizations intermittently lost access to social media platforms during COVID. Yet censorship has deepened the martyrdom ingrained in this theodicy of misfortune. A spiritual war against invisible enemies animates their imaginations and elevates their personal disappointment to the status of a historical event. Rebaptized in nature’s holy immunity by ascetic protocols of abstinence and purification, they turn over a new leaf, as it were, and crave vindication above all else. “This book offers you two messages,” Bernard Rimland promised of the testimonials that he collected in Recovering Autistic Children: “You are not alone in your fight, and you can win.”

Here’s another message: Children need love and respect above all. As René Dubos wrote in Mirage of Health, “As far as life is concerned, there is no such thing as ‘Nature.’ There are only homes.” ![]()

About the Author

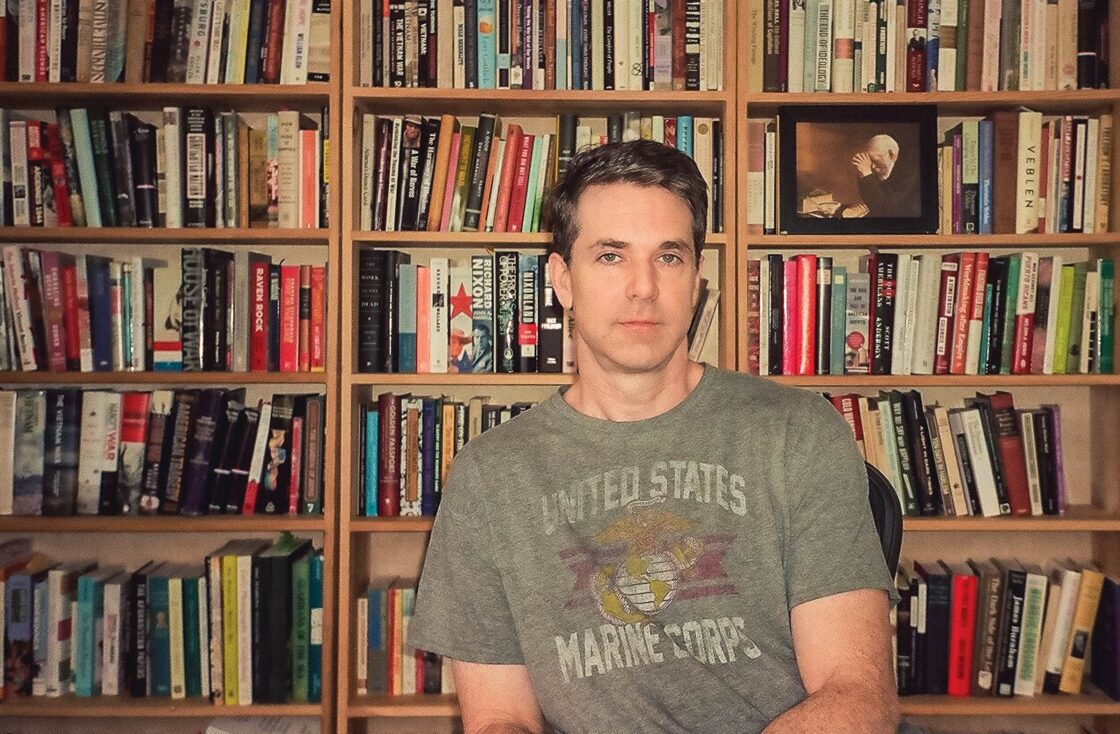

John Summers is a writer, historian, and Editor-in-Chief of Lingua Franca Media, Inc., an independent research institute in Cambridge, MA. He received his PhD in American history from the University of Rochester. For a decade, he taught at Harvard University, Boston College, and Columbia University. After leaving academia, he edited The Baffler magazine for five years. He is a father of a boy with autism.

This article was published on February 8, 2024.