If you want to make sense of GDP, inflation, interest rates, and economic policy, this is the article for you. We will address the following questions:

- What is the secret to the success of capitalist nations, which have grown by leaps and bounds in the past 200 years?

- What drives the economy — consumer spending, business investment, or government stimulus?

- Why are young people so attracted to democratic socialism, and is there a better alternative?

- Should valuable goods and services such as college education, medical services, and transportation be made available to the public for free?

- What is money, what is it based on without a gold standard, and can cryptocurrency ever replace it?

- Are booms and busts and periods of inflation and recession (like we’re experiencing now) inevitable?

- Do economists offer any solution to the global warming threat?

To answer the first question, let’s start from the beginning. In 1776, the same year the American colonies declared their political independence, a Scottish professor of moral philosophy, Adam Smith, wrote a declaration of economic independence called The Wealth of Nations, although its full title reveals it to be a work of behavioral science: An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. It was the first major treatise in economics; it became a bestseller, and Adam Smith became known as the “father of modern economics.”

Professor Smith Goes to Washington

In his classic work, Smith addressed the question, “What public policy would be the most conducive to increase the wealth of nations?” His model was revolutionary. As Columbia professor (and founder of the National Bureau of Economic Research) Wesley Mitchell stated, “Adam Smith did for economics in many ways like what Charles Darwin did for biology…a new framework.”1

Basically, Smith rejected the traditional model of authoritarian government at the time. Back then, the state had its hands in everything. England, France, Russia, and other European states constantly interfered in the economy by regulating foreign trade, granting monopolies to certain industries, licensing various occupations, setting wage rates, and even requiring permission to move from one town to another. Labeled “mercantilism,” the government sought to control every aspect of economic life with the purpose of achieving the most rapid growth of a country’s wealth. Exploitation of precious metals, a favorable balance of trade through high tariffs, and wars against nations were used to succeed at the expense of other nations. As Bertrand de Jouvenel observes, “Wealth was therefore based on seizure and exploitation.”2

That, however, wasn’t working. Progress was painfully slow, and life for most humans was, in the oft-quoted observation of the English political philosopher Thomas Hobbs, “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.”3 Adam Smith devised a solution. He contended that wars, tariffs, and regulations were not only mostly counter-productive but actually decreased the wealth of nations. He proposed a radical alternative, which he labeled a “system of natural liberty” — that the wealth of nations could increase much faster if everyone was allowed the fullest opportunity to pursue their own self-interest, that is, to have the freedom to trade, chose an occupation and business, and to decide for themselves how best to use their labor and capital without government interference. He believed his policies would reduce tensions between nations and allow everyone to improve their standard of living.

Smith wrote, “Every man, as long as he does not violate the laws of justice, is left perfectly free to pursue his own interest his own way, and to bring both his industry and capital into competition with those of any other man, or order of men” (emphasis added).4 As Wesley Mitchell concludes, “You see how bold and sweeping that argument is from Adam Smith’s eyes…it is evident, in his own local situation, [that man] is a better judge of where his economic interest lies than any statesman could be. Therefore, the individual will get on best if he is left alone by the government… This is the great argument for laissez faire.”5

The Scottish philosopher did not use the term “laissez faire” or “free market capitalism” to describe his model, but rather a “system of natural liberty” and occasionally “the invisible hand.” It consisted of five basic themes:

- Pro-savings, capital investment, and entrepreneurship

- Limited government (laissez faire)

- Balanced budgets, except in times of war

- Sound money (gold/silver standard)

- Free trade.

Smith boldly predicted that if a nation adopted his model of competitive free enterprise, limited government, sound money, and free trade, there would be “universal opulence which extends itself to the lowest ranks of the people.”6 It would liberate all people and all nations, rich and poor, from the drudgery of never-ending poverty into a new era of prosperity. On another occasion, Smith opined, “Little else is required to carry a state to the highest level of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice.”7

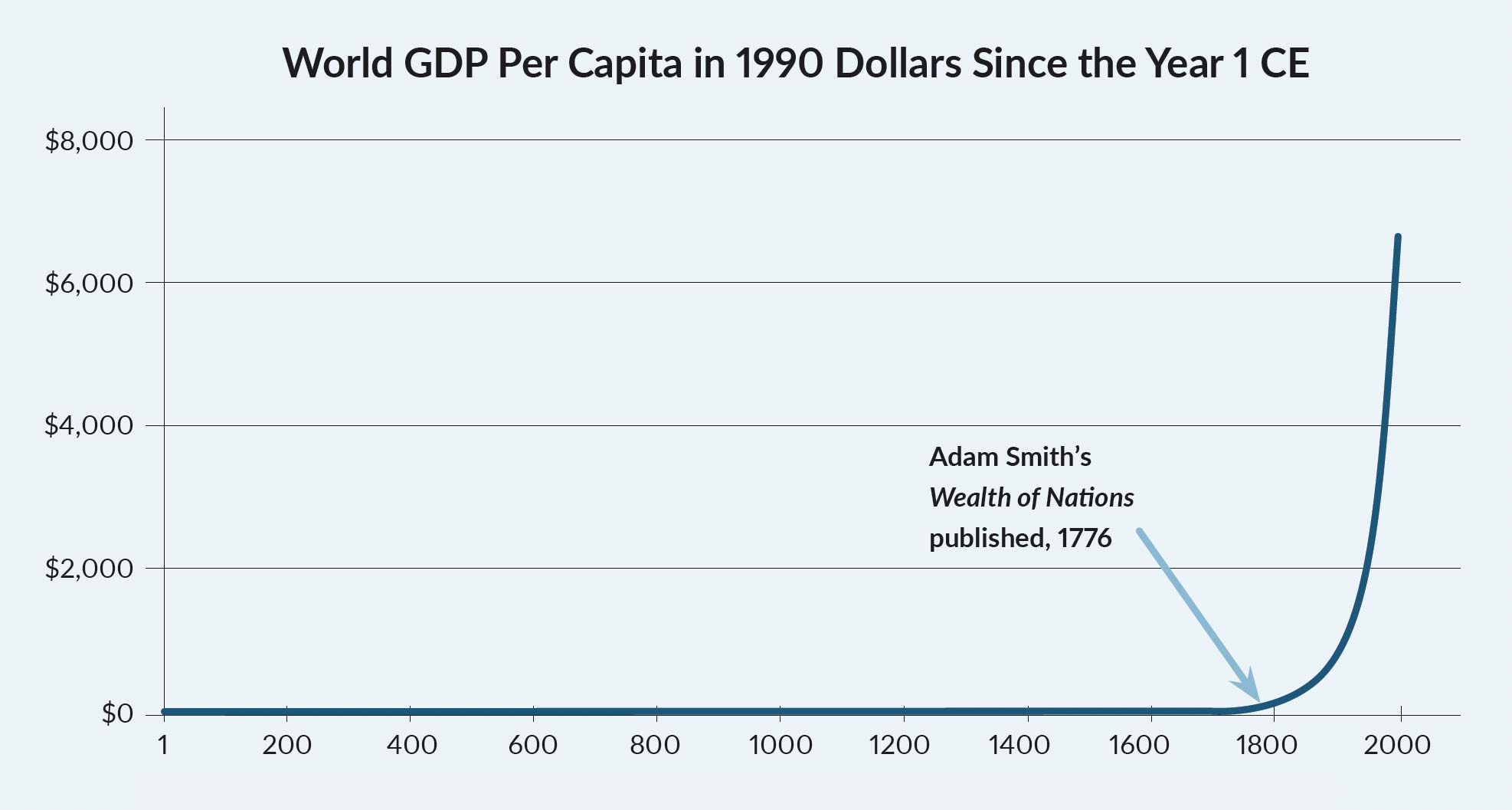

Figure 1. Source: Statistics on World Population, GDP, and Per Capita GDP. 1–2000 CE. Angus Maddison; IMF

Standard of Living

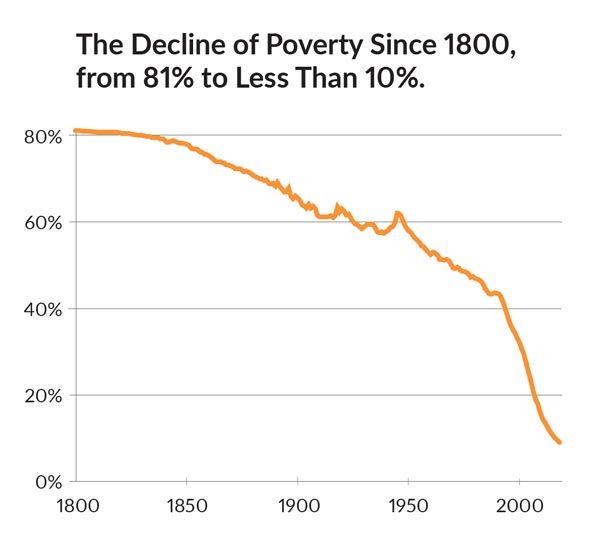

Indeed, it wasn’t long after the publication of The Wealth of Nations that the West witnessed the industrial revolution and a dramatic leap in prosperity, as Figure 1 demonstrates: Poverty also declined dramatically over the past 250 years. The percentage of people who earn no more than $2 a day has fallen from 81 percent in 1800 to less than 10 percent today, as tracked in Figure 2.

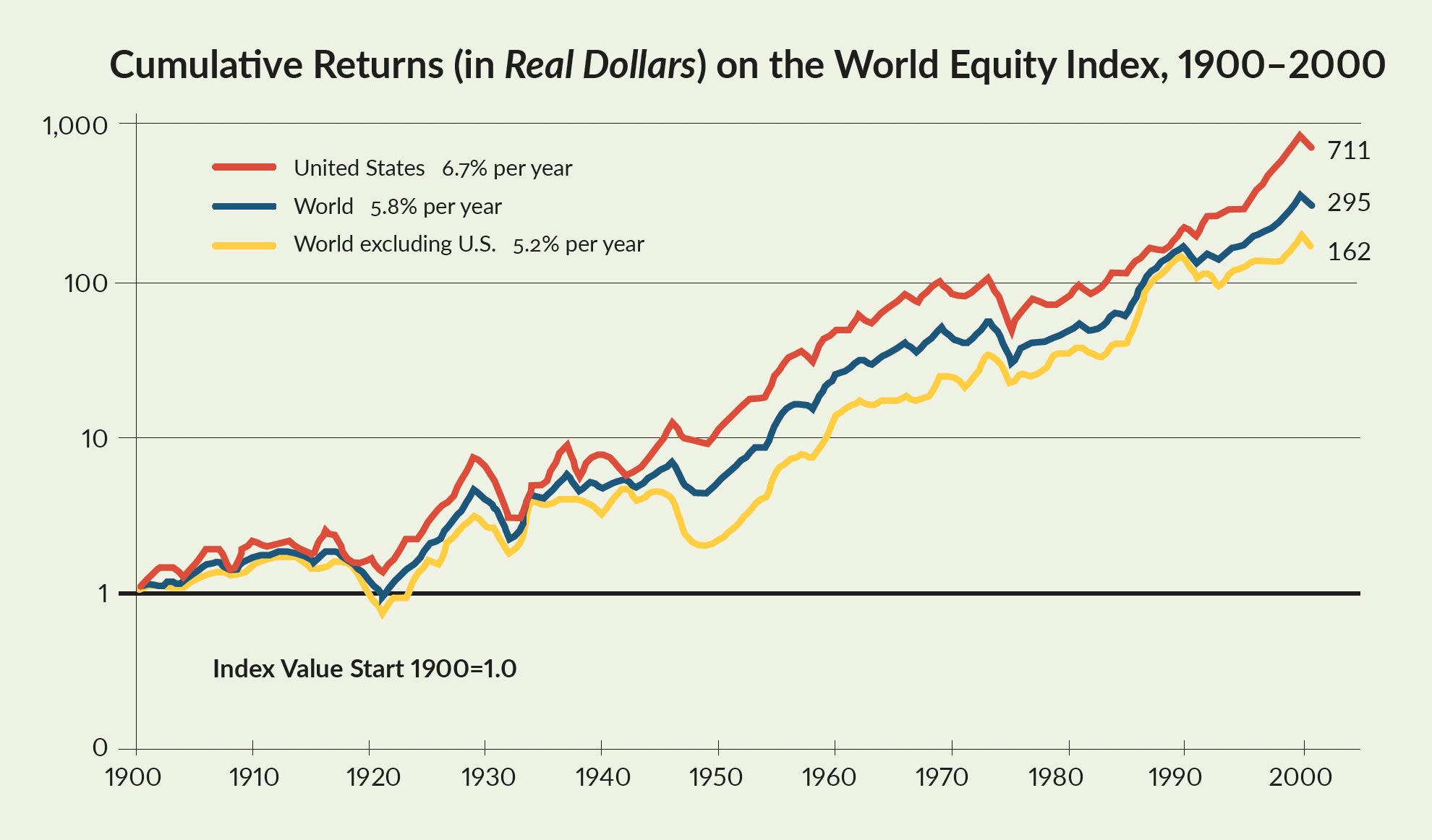

Another metric of higher living standards is stock market performance. Figure 3 demonstrates what economists call “the triumph of the optimists” in the 20th century.

Figure 3. A century of stock market performance for the United States, the world (including the U.S.), and the world (not including the U.S.). Credit: Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh, and Mike Staunton, Triumph of the Optimists. Princeton University Press, 2002.

Despite two world wars and the Great Depression, stock markets in 34 countries (in North America, Europe, and Japan) have enjoyed an upward trend. The red line represents “American Exceptionalism” — Wall Street having outperformed all other major country stock markets since 1900.

Of course, correlation is not necessarily causation. How much of the leap in output, reduction in poverty, and bull markets was due to the policies recommended by Adam Smith?

We know that his book was an instant bestseller, and was translated over time into all major languages. The classical model of low taxes, free trade, and the gold standard was in fact adopted gradually by Britain and then the United States, followed by other nations. Not all countries adopted the Adam Smith model — the Soviet Union and the Middle Eastern nations being the chief examples — but gradually, most did.

Smith’s laissez faire policy — that “government governs best which governs least,” in the words of Henry David Thoreau — became a popular cause in the 19th century, when the West imposed constitutional limitations on government power, reduced tariffs, and adopted the gold standard.

To be clear, Adam Smith was no anarchist. He saw a vital role for government to establish a “tolerable administration of justice,” the rule of law, the need for military defense, and public works, including public education. Overall, however, he advocated far less government intervention than nations had practiced in the past.

Economic Freedom Index Confirms Adam Smith’s Model

Since the early 1990s, the Fraser Institute of Canada has rated most countries on their degree of economic freedom. They have found a direct correlation between the level of economic freedom and a country’s standard of living. The think tank uses five criteria linked to Adam Smith’s classical model to determine each nation’s level of economic freedom:

- Size of government

- Property rights and legal structure

- Sound money

- Trade policy

- Business regulation.

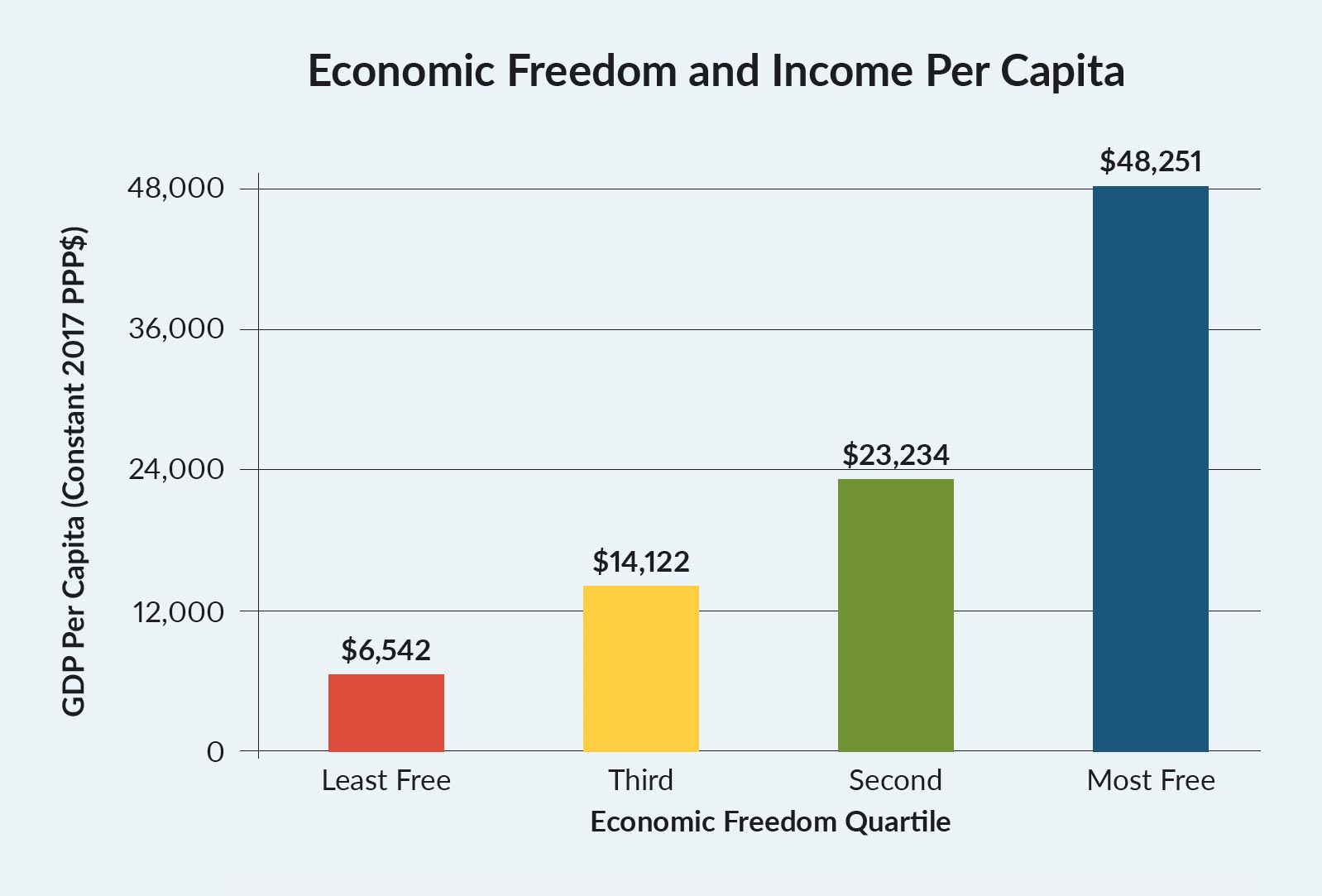

Their studies demonstrate that the freer the countries, the richer they are. Figure 4 shows their results.

Figure 4. Countries with greater economic freedom have substantially higher per capita incomes. Source: Economic Freedom of the World: 2022 Report; World Bank, 2022, World Development Indicators (online database).

What Drives the Economy

What is it about economic freedom that leads to higher and faster economic growth? The power to choose results in greater specialization, a comparative advantage, and increased productivity. Entrepreneurship and innovation in creating new products, better processes, and business management skills are the catalysts for a higher standard of living.

According to economists, the major factor in advancing an individual and a nation comes from the supply side of the economy — innovation, entrepreneurship, and new technologies, all funded by a generous pool of savings and investment capital. Countries that encourage high saving rates and creative inventions tend to grow faster. In this regard, America has been the land of opportunity for entrepreneurs from around the world to pursue their dreams.

Is GDP What It’s Made Out to Be?

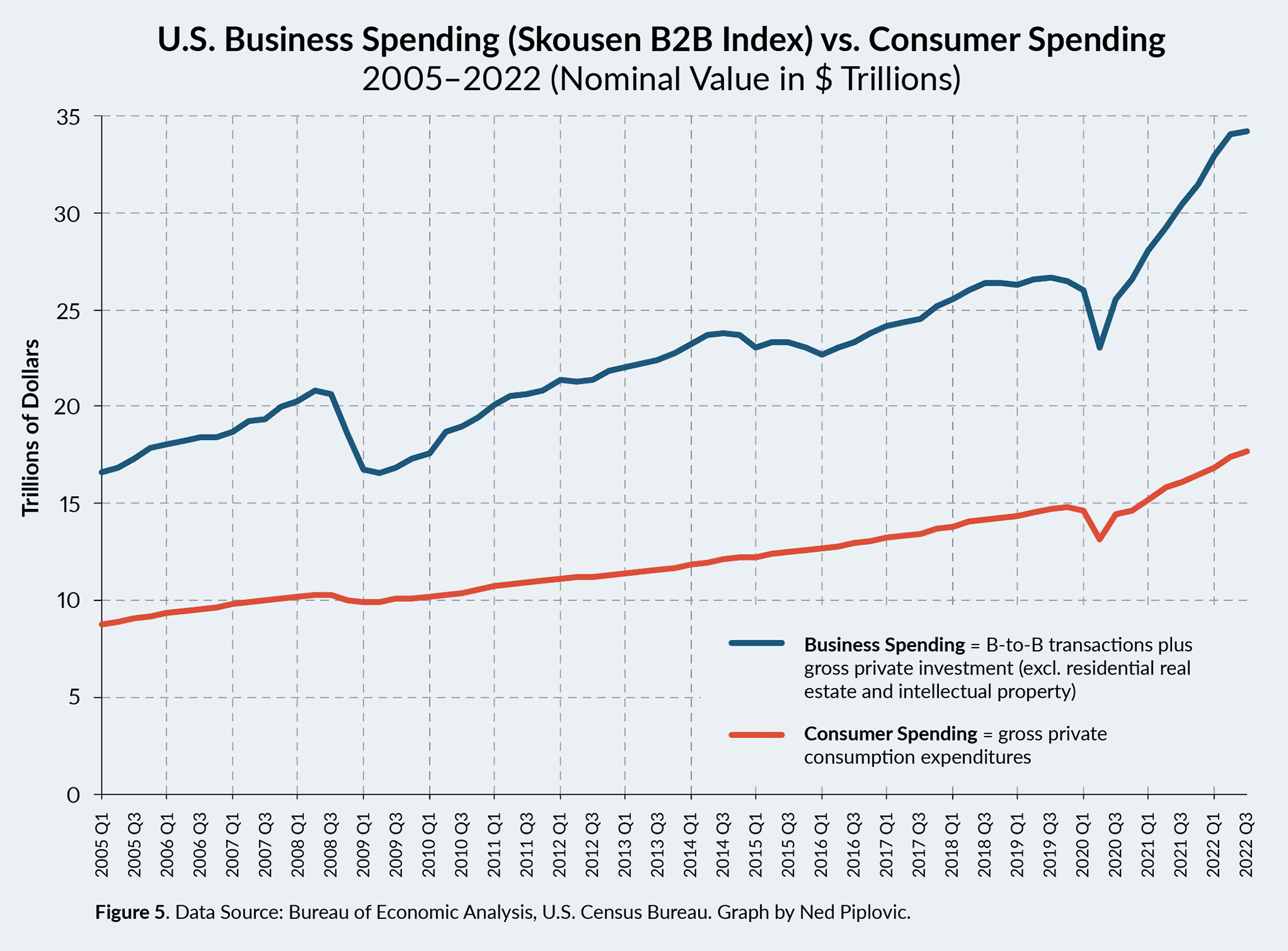

It is a popular myth that “consumer spending drives the economy,” a statement that comes from a misunderstanding of GDP. Gross domestic product (GDP) is the most common measure of the economy. It accounts for the final purchase of goods and services by consumers, businesses, and governments. Since consumer spending represents the largest sector of GDP — a full two-thirds — many media analysts conclude that it is consumption, rather than investment, that drives the economy.

However, the media and Wall Street analysts forget that GDP is not the same as “total spending in the economy.” GDP measures final output only — the finished goods and services that consumers, businesses, and government buy each year. It amounted to nearly $27 trillion 2022.

GDP is an important measure of our standard of living, but it leaves out some important elements of the economy. Most importantly, it omits the value of the supply chain — all the intermediate stages of production that move products and services along the production, wholesale, and retail sectors to the finished product. The value of the supply chain is larger than GDP itself, around $32 trillion this year!

When you include the supply chain, you get what the government calls gross output (GO). The federal government now publishes GO along with GDP every quarter. GO is a much better, broader definition of total economic activity because it measures spending at all stages of production. GO represents the “top line” of national income accounting, while GDP is the “bottom line.” Both are essential to understanding how the economy works.

Using GO as the complete measure of total economic activity, we learn that consumer spending is only one-third, not two-thirds, of GO. Thus, consumption is important, but not as important as business spending along the production process.8 Figure 5 demonstrates how much bigger and more volatile business spending (designated as B2B) is compared to consumer spending.

Thus, we see that business activity is the big elephant in the room and it is it that determines the economic success of a nation. Consumption is the effect, not the cause, of prosperity. As MIT professor Shlomo Maital concludes, “The health and wealth of a large number of individual businesses — small, medium and large — determine the economic health and wealth of a nation. When they succeed, managers create wealth, income, and jobs for large numbers of people. When they fail, working people and their families suffer. It is businesses that create wealth, not countries or governments. It is businesses that decide how well or how poorly off we are.”9

In the classroom, I use Seattle as an example. Why is Seattle a booming, prosperous metropolitan city today? Is it because its residents suddenly decided to buy more goods and services with their credit cards? No, it was innovative businesses that came up with new products that consumers didn’t know they wanted until the business engineers came up with the new ideas. I ask students to name these companies. They include Boeing (the 700 commercial jet series), Microsoft (Windows software), Starbucks (new kinds of coffee), and Amazon (the online everything store), among others. Granted, all of these companies needed customers to be profitable and to expand, but which came first, the consumer wanting these products, or creative entrepreneurs who invented the new product? Clearly the catalyst, the first mover, is on the business side of invention — on the supply side.

In economics, this is known as “Say’s Law of Markets,” named after the French economist Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832), known as the “French Adam Smith.” Dynamic change and economic growth come from the supply side.

Adam Smith Turns 300: Is His Model Still Relevant?

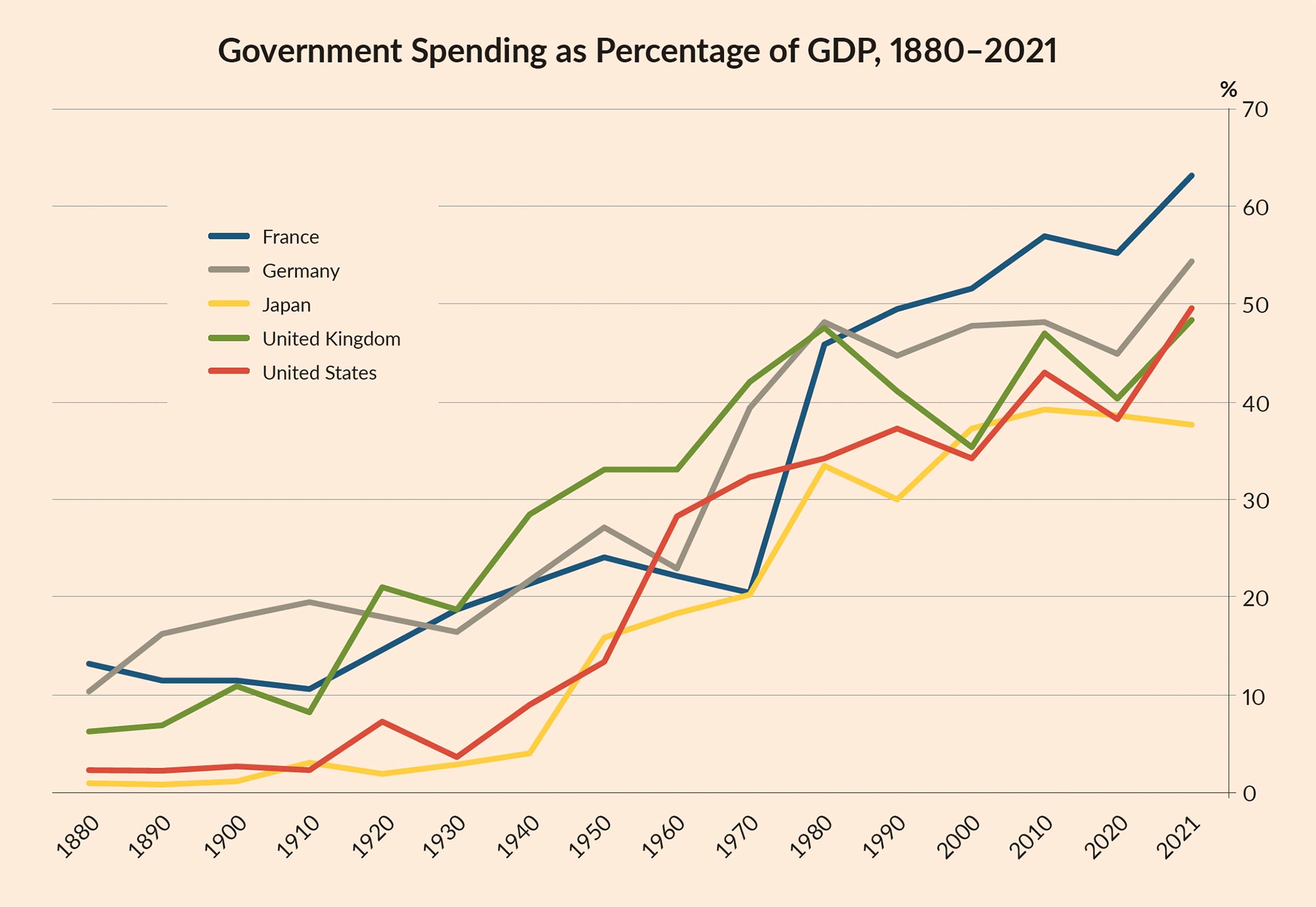

As we celebrate this year the 300th anniversary of Adam Smith’s birth (1723), it is appropriate to ask: How much of this classical model of economics is relevant today? In the face of world wars and occasional economic crises (especially the Great Depression of the 1930s), we see that most nations have largely moved away from laissez faire. Government has gotten bigger and more intrusive in almost every nation, although the differences between countries are still large (as evidenced by the Economic Freedom Index in Figure 4).

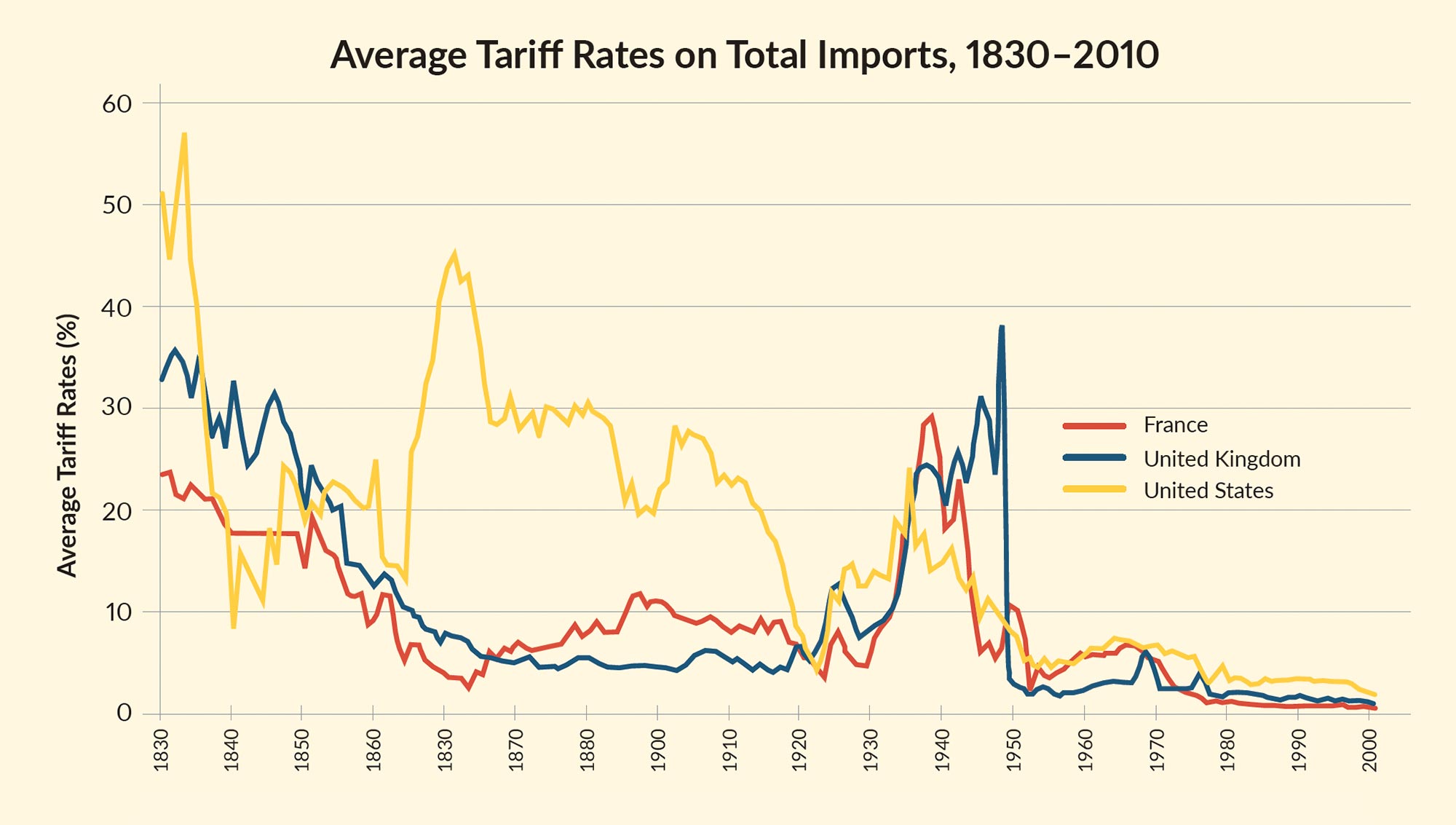

Figure 6. Average tariff rates from 1830 to 2010 comparing France, the UK, and the U.S. Sources: Imlah, Economic Elements

Certainly the Smithian doctrine of free trade has been the most successful policy recommendation. As we can see from Figure 6, most Western nations have gradually recognized the benefits of free trade and reduced and even eliminated the protectionist system of tariffs and quotas. Other countries have followed suit. Few countries depend on tariffs and duties as their primary source of revenue anymore. Even the “America First” doctrine has not materially raised tariffs. Globalization is here and it’s here to stay.

What about limited government? Not the case. As Figure 7 shows, governments of the developed world have grown dramatically since the 19th-century world of laissez faire was abandoned. In fact, there does not appear to be any evidence that government power has diminished among the major countries. One crisis following another has resulted in an ever-bigger government. Granted, marginal income tax rates on corporations have been declining for some time, but they have been offset by tax increases elsewhere, especially the Value Added Tax (VAT) and sales taxes, and by a dramatic rise in deficits and the national debt.

However, it is worth pointing out that the size of government (in terms of percentage of GDP) has declined sharply in the former Communist nations of Russia and the Eastern Bloc following the collapse of the Soviet Union and its central planning model. China has adopted “state capitalism” over “market capitalism,” but even there the size of government as a percentage of GDP fell sharply after 1980. Instead of 80 percent government control of the economy, China now controls less than 20 percent (in terms of GDP).

Why Has Socialism Failed Throughout History?

After the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet system in 1989–91, most authoritarian regimes liberalized their economies by cutting taxes, reducing regulations, privatizing government-controlled industries, and inviting foreign capital into their countries.

In very recent times, however, the appeal of “democratic socialism” has made a comeback, especially among young people, who are angry about inequality, attracted to the idea of free medical services (single-payer systems), free college tuition, and even free bus transportation in major cities, and enthusiastic about raising already progressive taxes on the rich to pay of these services. When I discuss the appeal of democratic socialism in lectures at colleges and universities, I begin by writing on the blackboard:

“From each according to his ability, to each according to his need,” and asking the students if this statement reflects their view of an ideal society. Usually two-thirds of the students vote in favor of it.

This is the classic motif of democratic socialism: You work hard, and you get what you need.

I then say, “Okay, students, let’s put our economics hat on and analyze the implications of this idealistic statement.”

First, I ask students, “How much money do you need to live comfortably?” The answer varies depending on the state where they grew up, but let’s assume on average they say around $50,000. Then I ask, “What happens if you make more than $50,000? Do you get to keep this money under this system?”

The answer is “no.” Any salary over $50,000 is put into the community pot to help out those who don’t make $50,000 and accomplish the goal of giving everyone what they need.

Finally, I ask, “What is the marginal tax rate under this system?”

Eventually, students come to the inevitable conclusion: It amounts to a 100 percent marginal tax rate, a confiscatory rate. Thus, we see there is little incentive for an individual to keep working after they earn $50,000.

Then I ask, what about somebody who earns only $30,000 a year? Under this model, they receive an additional $20,000 from the community fund. What incentive do they have to earn more than $30,000? None, because they get the additional $20,000 no matter what.

This exercise is an eye-opener to many students. They realize that no one in this system has an economic incentive to work for more, other than being a compassionate person. And that’s why socialism has failed time and time again. It doesn’t offer incentives to succeed, as an individual, a business, or a nation.

Only after this exercise do I point out that the statement is from Karl Marx.

Democratic Socialism or Democratic Capitalism?

Is there an alternative to democratic socialism that would appeal to most young people? It is at this point that I introduce what I call “democratic capitalism,” where everyone benefits from the market economy — not just capitalists, but employees, executives, customers, suppliers, investors, and the community. It’s called the “stakeholders philosophy.”

The story of Henry Ford’s $5-a-day policy is the best example of the stakeholder philosophy. The president of the Ford Motor Company did something revolutionary in 1914 — the maker of the Model T shared the profits with his workers by doubling their wages overnight to $5 a day. This was unprecedented. It not only improved the lives of the average worker, but it gave them enough money to buy the product they were making, the automobile. In one day, Henry Ford destroyed the two biggest arguments by the Marxists against capitalism — exploitation and alienation.

Today there are many examples of businesses that share their success with their workers through profit sharing, stock options, and 401(k) plans. For example, over 12,000 employees at Microsoft have become multi-millionaires because of their stock option plan. The inequality issue could be minimized if more businesses engage in profit sharing.

Should Essential Needs be Free?

The free enterprise system is built on the pricing mechanism, which operates as a rationing system. Since we live in a world with limited resources and unlimited demand, prices develop for all goods and services, and those prices vary according to supply and demand.

One thing almost all economists agree on today is that free-enterprise capitalism is the best model to fulfill our ever-expanding needs and wants. It has produced an unparalleled increase in the quantity, quality, and variety of goods and services that no socialist government could imitate. In my Chapman University economics class, I ask a student to go to a large grocery store and find out how many types of bread there are; and another student to go to a liquor store and find out how many types of beer there are. (The answers will astonish you.)

As socialist historian Robert Heilbroner declared that after the collapse of the Berlin Wall: “Capitalism has won. Capitalism organized the material affairs of humankind more satisfactorily than socialism: that however inequitably or irresponsibly the marketplace may distribute goods, it does so better than the queues of a planned economy; however mindless the culture of commercialism, it is more attractive than state moralism; and however deceptive the ideology of a business civilization, it is more believable than that of a socialist one.”10

However, socialism is not dead by a long shot. Advocates criticize the capitalist model for creating growing inequality of wealth and income, and causing pollution and global warming. Critics of capitalism also complain that the free market cannot provide adequate goods and services to the poor at a reasonable price, and therefore, the best solution is to offer subsidized or free education, transportation, medical services, food, and other essentials to the less fortunate.

In response, I do an exercise with my students on whether the marketplace can fulfill the needs to the rich, the middle class, and the poor. I ask students to examine a variety of needs in society — for example, automobiles, hotels, restaurants, housing, and entertainment — and see how well the marketplace fulfills those needs at each income level.

Students quickly identify markets in these industries for the rich, the middle class, and the poor. For example, there are automobiles for the rich (Mercedes Benz, Lexus, and Tesla), for the middle class (Toyota, Honda, Buick), and for the poor (Chevrolet, Ford, and Kia). There are hotels for the rich (Ritz-Carlton), the middle class (Hilton), and the poor (Motel 6). There are restaurants for the wealthy (Ruth’s Chris Steak House), the middle class (Red Lobster), and the poor (McDonald’s). Conclusion: Capitalism is not just for the rich.

Moreover, the profit motive and competition results in better, cheaper, and newer products being created all the time by entrepreneurs in what Joseph Schumpeter termed “the creative destruction” of dynamic capitalism. (I prefer the less harsh term “creative disruption” popularized by Harvard’s Clay Christensen). As Andrew Carnegie said, “Capitalism is about turning luxuries into necessities.” Big-screen 4K televisions used to cost upwards of $5,000, now they are under $500. One of the fun exercises I do with my students is to create two lists: new products and services that didn’t exist 30 years ago, and old products and services that are now obsolete. Students love discovering how long both lists are.

“Cheaper and better” is the best way to describe the benefits of free enterprise. The exceptions tend to be government-run or government-controlled industries, such as medicine and the post office.

What about inequality? It is true that in recent years during the bull market on Wall Street, there is evidence of growing inequality of wealth and income. However, as I point out to my students, when it comes to the quantity, quality, and variety of goods and services, that inequality gradually disappears. I hold up a smartphone as an example. Almost everyone from rich to poor has a smartphone, which contains an almost unlimited source of knowledge and wisdom. It’s today’s great equalizer.

The Danger of Offering Valuable Products and Services for Free

Despite the benefits of free-market capitalism, there is a growing demand by young people that the government provide free services in education, medicine, and transportation. Surveys show that most college students are worried that the average person can no longer afford a decent higher education or adequate medical care. Note that these two areas are where there are heavy government regulation and subsidies.

“Cheaper and better” applies to almost all goods in the market economy, but not education or medical services. They tend to more expensive and show little improvement recently. Why? Public education is highly subsidized in the United States through federal grants and student loans, yet SAT scores have not improved, indeed, the U.S. is falling behind other nations on standardized educational average test performance. The budget for the U.S. Department of Education exceeds $650 billion a year. Where are the results?

One of the grand principles of economics is that “There is no such thing as a free lunch.” Somebody has to pay, and in the case of free medical services and education, it is the taxpayer.

Offering valuable goods for free also violates one of the cardinal principles of economics: the accountability principle, or “user pays.” Those who benefit should pay. Why? Because they are aware of the cost, they shop around for the best deal, and they demand quality for their money.

Should a valuable service like college education be free, as Senator Bernie Sanders and other democratic socialists advocate? Germany has offered free tuition for college students for years, and the results have been mixed, with problems of overcrowding of classrooms, poor selection of majors, and fewer funds for research.11

In medicine, the all-important principle of accountability is often violated. Those who benefit do not pay. Instead, a third party pays — your employer, your insurance company, or the government. This is known as the “third party problem.” Patients often don’t know the actual cost of their medical expenses. This is especially true in countries that have socialized (single-payer) medical systems such as Canada and most European countries. There’s a disconnect between those who pay (taxpayers) and those who receive the benefits: long lines, shortages, and poor quality of care are common problems in many of these countries.12

The third-party problem is serious in the U.S. As a result, the medical system is expensive, uncompetitive, and often rife with insurance and Medicare/Medicaid fraud.

Singapore’s Medisave Success Story

What is the solution? Not the single-payer systems used in Canada and Europe. One of the best examples of a successful medical system is Medisave in Singapore. While the U.S. spends 18 percent of GDP on healthcare, Singapore spends only 4.7 percent, while providing universal healthcare to its citizens — and is ranked the number one most healthy country in the world — in terms of life expectancy, infant mortality, and maternal mortality.

And it does so inexpensively. For instance, major surgeries cost 62–92 percent less in Singapore than the U.S. A heart-bypass surgery that would cost $130,000 in the United States costs just $18,000 in Singapore.

They achieve this “cheaper and better” approach in medicine by requiring every worker to have a health savings account, with a high deductible and co-pays that workers can afford. Competition and shopping around for low prices are encouraged because employees pay for most routine expenses through their health savings accounts (accountability principle). A similar health-living program can be found at Whole Foods Market in the United States, with their health savings plans and wellness programs.13

Money, Inflation, and Bitcoin

Another major issue in society is the value of our currency. Money is the life’s blood of the economy. The dollar (and other currencies such as the euro and the yen) function as our primary medium of exchange and store of value. However, can we lose faith in the dollar if it loses its value, resulting in runaway inflation? A stable dollar is essential for businesses to operate efficiently. When inflation gets out of hand, it can wreak havoc on businesses, wage earners, and consumers. Once price inflation gets started, it’s hard to contain, because workers demand higher wages, consumers go into debt to buy now to avoid paying higher prices later, and businesses raise prices to keep ahead of rising costs, and also famously try to hide price increases by downsizing products (known as “shrinkflation”).

Rising inflation also causes the Federal Reserve and other central banks to raise interest rates to slow down the economy, often resulting in a recession or a monetary crisis. No wonder the stock market often tanks during a rise of inflation.

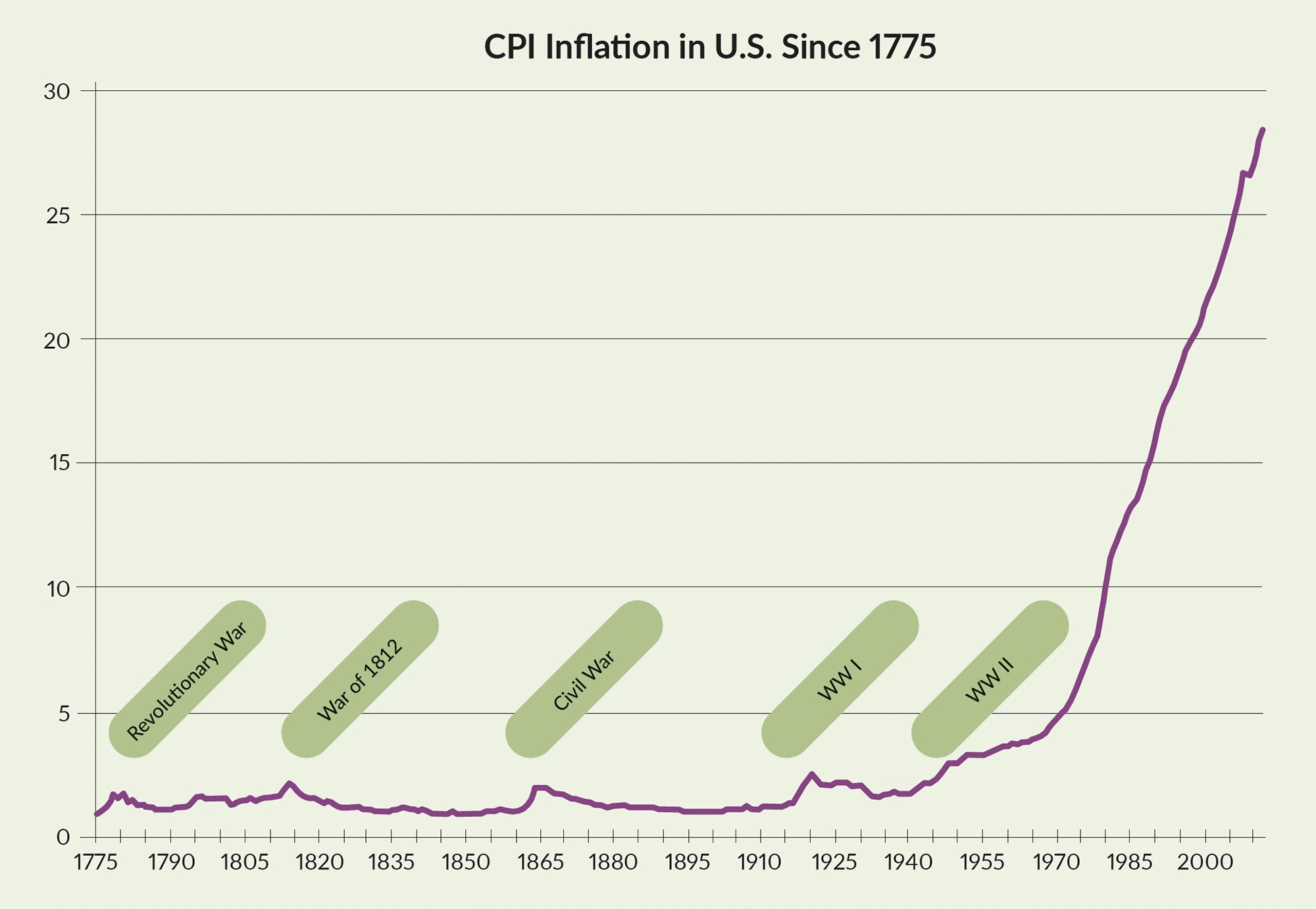

Figure 8. Source: Reinhart, C. & Rogoff, K. (2013) Shifting Mandates: The Federal Reserve’s First Centennial. American Economic Review 103:3, p. 48.

As Figure 8 demonstrates, price inflation used to raise its ugly head only during times of war, but since World War II, it has become a permanent feature of the U.S. economy.

There are plenty of excuses why inflation has gotten worse since World War II. They could include:

- Never-ending wars

- The creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913

- Going off the gold standard in 1933 and 1971

- Adoption of Keynesian economics (bigger government and never-ending deficit spending)

- All of the above.

Harvard economists Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff are convinced that the most critical factor was going off the gold standard by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1933 and completely disbanding gold by President Nixon in 1971, thus eliminating entirely the discipline of the gold standard, and allowing the government to print money (increase the money supply) as much as they wish.

The key to controlling the purchasing power of the dollar and other currencies is closely linked to controlling the supply of money and credit. Unfortunately, in today’s world, politicians and central banks are under constant pressure to expand the money supply and engage in easy money.

Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies have become a private alternative to the dollar as a medium of exchange, speculative asset, and inflation hedge, because of limited supply, like gold. Bitcoin, created in 2008 by a mysterious person named Satoshi Nakamoto, can be “mined” through open-source software and is limited to 21 million coins. Bitcoin transactions are recorded on a public ledger called a blockchain. The price of bitcoin, Ethereum, and other cryptocurrencies have soared as an alternative currency, but have faced serious challenges, including delays in recording transactions on the blockchain, lack of regulation, tax complications, and fraudulent business practices exemplified by the FTX debacle. The blockchain technology clearly has great potential in business, real estate, and the financial markets, but the outlook for bitcoin and other digital currencies is still uncertain and speculative, depending on how well governments handle the inflation problem.

The last great Federal Reserve chairman was Paul Volcker, who ran the Fed from 1979 until 1987 during the Carter and Reagan administrations. By raising interest rates to 21 percent and curtailing monetary expansion, Volcker successfully overturned the entrenched inflationary psychology that was built into the American economy since World War II. We entered a period of disinflation — no real deflation — and then, like an old penny, inflation came back with a vengeance after the 2020 pandemic. The Trump and Biden administrations engaged in aggressive fiscal (big spending, tax cuts, and trillion-dollar deficits) and monetary (easy money) policies combined to overstimulate the economy to offset the global pandemic lockdown. We are now paying the price with an inflationary boom-bust cycle.

The Boom-Bust Cycle

That brings us to this question: how do we control the ups and downs of economy, money and credit, and minimize the never-ending cycle of inflationary booms followed by recessions or worse? The key solution is twofold: The Federal Reserve’s monetary policy needs to be one of stability rather than a never-ending battle between “fighting recession” and “fighting inflation.” The Fed has changed directions between easy money (cutting interest rates) and tight money (raising interest rates) nearly a dozen times since 1980. And fiscal policy (taxes and spending) needs to be dependable and restrained, living within its means during full employment and so minimizing federal deficits. That will make the Fed’s job easier.

Environmentalism and the Global Warming Threat

Economists have made significant contributions to the debates over ecology and climate change. Yale professor William Nordhaus was awarded the Nobel prize in economics in 2018 for his pioneering work on the economic impact of rising global temperatures and the “negative externalities” of air and water pollution.

According to economists, the best way to reduce smog and curtail the emission of greenhouse gases is through a combination of new technologies in the private sector and to impose high carbon taxes on polluters. Instead of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) trying to discover a way to reduce automobile emissions, they set strict emission limits and higher fuel mileage standards and let engineers in the car and truck manufacturers come up with a solution — which they did. Starting in 1975, automobiles, trucks, and buses were equipped with the newly invented catalytic converter.

To demonstrate the results of these government regulations, I do a survey every year with my students in Southern California. I ask them, “Since 1960, has air pollution gotten better or worse in the LA area?” Typically 60–70 percent say “worse.” Then I show them Figure 9 (previous page).

Figure 9 shows two trends — increased use of cars and trucks on Los Angeles freeways, and at the same time a dramatic 97 percent reduction in air pollution, thanks to the catalytic converter and other government regulations. Students are shocked. I tell them how in the 1960s the smog was so bad that it was almost impossible to see downtown LA or Catalina Island. Now, most days are clear. The near elimination of smog in Southern California is truly an environmental success story.

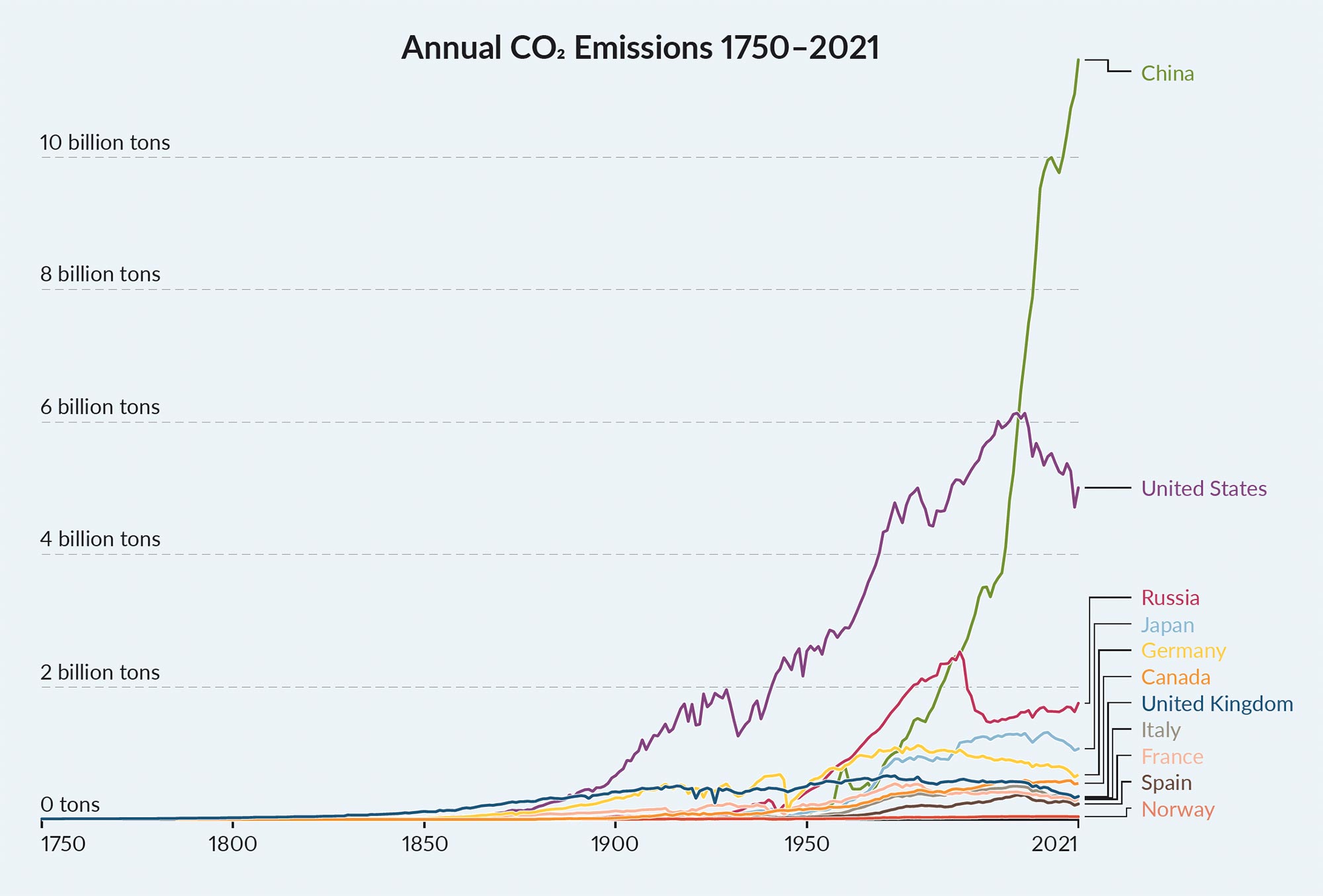

The United States and Europe have made great strides in reducing greenhouse emissions. The real problem lies with developing countries such as China and India, as Figure 10 shows.

Figure 10. Annual total production-based carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fossil fuels and industry, excluding land-use change, measured in tonnes (based on territorial emissions, which do not account for emissions embedded in traded goods). Source: Our World in Data (2022) (CC BY 4.0) based on the Global Carbon Project.

Economists tend to be more skeptical and less alarmist regarding the environmental and global warming threats because they are solution-oriented, see progress, and advocate a cost-benefit analysis to these hot-button issues. William Nordhaus has been criticized by both environmental alarmists and by global warming skeptics. He believes global warming is a real threat, but as an economist, he is also alert to the dangers of going overboard: “If, for example, attaining the 1.5°C goal would require deep reductions in living standards to poor nations, then the policy would be the equivalent of burning down the village to save it.”14

The Future

Ideally, we would like to live in a prosperous society promised by Adam Smith through “peace, easy taxes, a tolerable administration of justice,” and let’s add stable prices, a clean environment, and maximum liberty for all. Is this ideal society beyond reach?

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 28.1

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

Perhaps. I see slow growth ahead, punctuating by recessions from time to time, with the world being burdened with a growing military-industrial complex, a bloated bureaucracy, excessive government debt, more debilitating regulations, a permanent welfare state, an incredibly complex tax system, and politicians falling all over each other to throw more money at their respective pet projects. New technologies can mitigate these burdens, but not entirely. Perhaps there is a white knight out there coming to put America back on a sound fiscal and monetary basis, but I fear Humpty Dumpty has fallen and can’t be put together again. I don’t see America becoming another Venezuela, but neither do I see it as another Singapore.

It’s easy to become pessimistic. Perhaps we can learn something from Adam Smith, who was the ultimate optimist. Nearly 250 years ago, he wrote:

The uniform, constant, and uninterrupted effort of every man to better his condition… is frequently powerful enough to maintain the natural progress of things toward improvement, in spite both of the extravagance of government, and of the greatest errors of administration.15

Economic Terms Used in This Article

- Gross Output (GO)

- the market value of all goods and services produced at all stages of production in a year in a country; considered the “top line” in national income accounting.

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

- the market value of all final goods and services produced in a year in a country; considered the “bottom line” in national income accounting and standard measure of economic growth.

- Consumer Price Index (CPI)

- the weighted average of prices of a basket of consumer goods and services; released monthly by the US Bureau of Labor.

- Invisible hand doctrine

- the idea advocated by Scottish economist Adam Smith (1723–1790) that the voluntary actions of individuals will benefit society in general.

- Say’s Law of Markets

- Developed by French economist J.-B. Say (1767–1832), the supply-side theory that economic growth is determined by changes in production and the supply of new goods and services (often said in short hand, “supply creates demand”) and an economic policy that encourages technology, entrepreneurship, savings and capital investment.

- Keynesian Economics

- Developed by British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), the theory that economic activity is determined by changes in aggregate spending by consumers, business and government (often said in short hand, “demand creates supply”), and an economic policy that advocates big government deficit spending and during economic downturns.

- Marxist Economics

- Developed by German economist Karl Marx (1818–1883), the theory that capitalism is exploitive (capitalists don’t share the profits with workers) and destabilizing, and will eventually collapse and be replaced by socialist central planners who operate the means of production.

- Gold Standard

- a monetary policy where a country’s money (such as the dollar) is backed by gold, and monetary policy is limited by the rise and fall in the supply of gold.

- The Fed

- Short for the Federal Reserve, the central bank of the United States, which determines the supply of money and credit, the price of money (interest rates), and the lender of last resort during a financial or economic crisis.

- Laissez faire

- French for “let us alone,” the philosophy that government should not interfere with the actions of individuals as consumers and business people.

- Democratic Socialism

- the philosophy that government (elected by the people) should provide the basic needs (food, shelter, medical services, education) for the public and be paid for by progressive taxation.

- Democratic Capitalism

- the stakeholder philosophy that successful businesses should fulfill the needs of customers, and share the profits with their employees, suppliers, investors, and the communities they operate in.

About the Author

Mark Skousen is a Presidential Fellow and the Doti-Spogli Endowed Chair of Free Enterprise at Chapman University. He has a BA, MA, and PhD in economics (George Washington University, 1977). In 2018, Steve Forbes awarded him the Triple Crown in Economics for his work in theory, history, and education. He has taught economics, business and finance at Columbia Business School and Columbia University. He has worked for the government (CIA), non-profits (president of FEE), and been a consultant to IBM and other Fortune 500 companies. He is the author of over 25 books, including The Making of Modern Economics and The Maxims of Wall Street. He has been editor-in-chief of an award-winning investment newsletter, Forecasts & Strategies, since 1980. He produces “FreedomFest, the world’s largest gathering of free minds,” every July in Las Vegas and other cities. His website is skousenbooks.com.

References

- Mitchell, W.C. (1934). Lecture Notes on Types of Economic Theory (p. 13). Hassell Street Press.

- De Jouvenel, B. (1999). Economics and the Good Life (p. 100). Transaction.

- Hobbs, T. (1996/1651). Leviathan (p. 84). Oxford University Press.

- Smith, A. (1965/1776). The Wealth of Nations (p. 651). Modern Library.

- Mitchell, Lecture Notes, pp. 15–17.

- Smith, The Wealth of Nations, p. 11.

- 1755 lecture by Adam Smith, recorded by Dugald Stewart, cited in Clyde E. Danhert, ed., Adam Smith, Man of Letters and Economist (p. 218), Exposition, 1974.

- https://www.grossoutput.com/

- Maital, S. (1994). Executive Economics (p. 6). Free Press.

- https://bit.ly/3WUSEiN

- See for example Jon Marcus, https://bit.ly/3QgeHh9

- For a critique of the Canadian single payer system, see https://bit.ly/3CcWOtF

- Flynn, S. (2019). The Cure That Works: How to Have the World’s Best Healthcare at a Quarter of the Price. Regnery.

- Nordhaus, W.D. (2018). Climate Change: The Ultimate Challenge of Economics (p. 451). Nobel prize lecture.

- Smith, A. (1965/1776). The Wealth of Nations (p. 326). Modern Library.

This article was published on May 9, 2023.