The cliché that “there is nothing new under the sun” applies more than ever to the mental health profession today. We seem to be experiencing a myriad of new techniques to treat the developmentally disabled, Facilitated Communication being one of the most popular, yet in reality their underlying characteristics have been seen before. These components make up the structure of what might be considered a social movement:

- Assertions that a new technique produces remarkable effects are made in the absence of solid objective evidence, or what little evidence there is becomes highly overblown.

- Excitement about a possible breakthrough sweeps rapidly through the communities of parents, teachers, service providers, and others concerned with the welfare of individuals with disabilities.

- Eager, even desperate for something that might help, many invest considerable financial and emotional resources in the new technique.

- In the process, effective or potentially effective techniques are ignored.

- Few question the basis for the claims about the new treatment or the qualifications of the individuals making them.

- Anecdotal reports that seem to confirm the initial claims proliferate rapidly.

- Careful scientific evaluation to determine the real effects of the technique are not completed for some time, and can be made more difficult than usual by the well-known and powerful effects of expectancies.

- Some of these techniques have small specific positive effects, or at least do minimal harm.

- Eventually they fall out of favor, sometimes because they are discredited by sound research, sometimes simply because experience reveals their lack of efficacy, but probably most often because another fad treatment has come on the scene. Each retains some adherents, however, and some go relatively dormant for a while only to emerge again.

Parallel phenomena occur in other areas, such as treatments for AIDS, cancer, and various psychological problems. At present the field of developmental disabilities (especially autism) seems to be experiencing an epidemic of novel techniques, or “interventions,” as they are called. Despite its parallels with other techniques, Facilitated Communication (FC) has probably had a greater impact than any other novel intervention in the history of treatment for persons with disabilities.

How FC Works

How does FC work? If you have never seen it in action it is quite a phenomenon to observe. Individuals with “severe communication impairments” (e.g., severe mental retardation, autism) are assisted in spelling words by “facilitators” (teachers or parents) who provide physical support, most often (at least initially) by holding their hand, wrist, or forearm while they point to letters on a keyboard or printed letter display. Right before your eyes, a mentally disabled person that just previously had virtually no communication skills, suddenly begins to spell out words, sentences, and whole paragraphs. Stories are told. Answers to questions are given. A child that did not appear to know the difference between a dog and an elephant can now be shown a series of pictures, correctly identifying them one by one, as his or her hand glides deftly over the keyboard, pecking out the correct letters. The assumption, of course, is that most of the words spelled in this fashion actually originate with the disabled partner and not the facilitator.

On its face, FC can seem simple and benign, and sometimes looks quite convincing. Its main proponents sometimes characterize FC simply as a strategy for teaching individuals to point in order to access systems like synthetic speech devices and keyboards to augment their communication. At the same time, however, they claim that it is a revolutionary means of unlocking highly developed literacy, numeracy, and communication repertoires in large numbers of individuals previously thought to have severe learning difficulties. For all the world it looks like a mental miracle, the kind of stuff they make movies about, as in Awakenings.

The theory is that many such individuals do not have cognitive deficits at all, but instead have a presumed neuromotor impairment that prevents them from initiating and controlling vocal expression. Their average or even above average intelligence is locked away, awaiting release. The neuromotor disorder is also presumed to manifest itself in “hand function impairments” that make it necessary for someone else to stabilize the individual’s hand and arm for pointing, and to pull the pointing hand back between selections to minimize impulsive or poorly planned responding. Candidates for FC are also presumed to lack confidence in their abilities, and so require the special touch and emotional support of a facilitator to communicate, (i.e., a strap or device to hold the person’s arm steady will not work).

FC thus has an almost irresistible appeal for parents, teachers, and other caring persons who struggle mightily to understand and communicate with individuals who often do not respond or communicated in return. But the very features that make FC so seductive, in combination with some other potent factors, have made it a topic of heated debate between believers and skeptics since its “discovery” in Australia nearly two decades ago.

Beginnings Down Under

It all began in the 1970s with Rosemary Crossley, a teacher in an institution in Melbourne in the Australian state of Victoria. She suspected that some of her young charges with severe cerebral palsy had far more ability than their physical impairments allowed them to demonstrate. When she gave them hand or arm support to help them point to pictures, letters, and other stimuli, Crossley became convinced that several of the children revealed literacy and math skills that they had somehow developed with little or no instruction, despite having lived most of their lives in an impoverished institutional environment.

Right away there was controversy about the technique that Crossley called Facilitated Communication Training. Two people were involved in creating the messages, and simple observation could not reveal how much each was contributing. Plus, many of the messages Crossley attributed to these institutionalized individuals defied plausibility. “Facilitated” accusations of abuse and expressions of wishes for major life changes (like leaving the institution) made it imperative to determine whether communications actually originated with the disabled individual or the facilitator. Matters were complicated by Crossley’s emerging status as a heroine to many in the deinstitutionalization movement. Eventually, after a series of legal proceedings, a young woman with cerebral palsy with whom Crossley had developed a special relationship through FC was released from the institution to reside with Crossley. The institution was closed, and in 1986 Crossley started (with government financial support) the DEAL Centre (Dignity through Education and Language) to promote alternative communication approaches—principally FC—for individuals with severe communication impairments. Use of the method spread to programs in Victoria serving persons with various disabilities, accompanied by controversies about communications attributed to FC users on the basis of subjective reports.

Sufficiently serious issues arose to provoke formal statements of concern from professionals and parents in 1988, and a government-sponsored investigation in 1989. Despite Crossley’s resistance to objective testing (on the basis that FC users refused to cooperate when their competence was questioned), some small-scale controlled evaluations were conducted in the course of that investigation. When the facilitator’s knowledge about expected messages was well-controlled (more on this later), and the accuracy of messages was evaluated objectively, the effect disappeared. The disabled individuals were unable to communicate beyond their normal expectation. Instead, it appeared that the facilitators were authoring most FC messages, apparently without their awareness. These early studies suggested that FC was susceptible to a somewhat unusual kind of abuse: Allowing others to impose their own wishes, fears, hopes, and agendas on nonspeaking individuals.

A Social Movement is Born

At about that time Douglas Biklen, a special education professor from Syracuse University, conducted a four week observational study of 21 DEAL clients said to be autistic, who were reported to engage in high-level discourse with the help of facilitators. Professor Biklen was already established as a leader in the “total inclusion movement,” which seeks the full-time placement of all students with disabilities, regardless of their competencies and needs, in regular classrooms. The report describing his first qualitative study of FC, which Biklen said was begun “in an attempt not to test hypotheses but rather to generate them,” appeared in the Harvard Educational Review in 1990. He reported that the communication of the individuals he observed (some of whom were being “facilitated” for the first time) was sophisticated in content, conceptualization, and vocabulary, and contained frequent references to feelings, wishes to be treated normally and to attend regular schools, and society’s treatment of individuals with disabilities.

Can people learn, without being deliberately taught, to respond to subtle, subconscious, involuntary cues if an animal can? In the early 1900s, a horse, Clever Hans, astonished Germany by its self-learned ability to interpret visual cues and answer simple questions by tapping its hoof.

This was in sharp contrast with the well-documented difficulties in social, play, cognitive, and communication skills that constitute current diagnostic criteria for autism (not to mention that the diagnosis is difficult to make and is applied to individuals with a wide range of competencies and deficits in all those domains). In his seminal article, Biklen mentioned the controversy over the Australian findings, but asserted that informal “indicators that communication was the person’s own were strong enough, in my view, to justify the continuing assumption of its validity” [italics added].

Some of the indicators he reported observing were disabled individuals typing independently or with minimal physical contact with the facilitator; content (spelling errors, unexpected word usage, etc.) that appeared to be unique to each individual; and facial expressions or other signs that the individual understood the communication. He also noted that facilitators often could not tell who was doing the spelling and that they could be influencing the FC in subtle ways without their awareness, and that this could be a problem. Finally, on the basis of his uncontrolled observations and the reports of Crossley and other facilitators, Biklen decided that autism had to be redefined as a problem not of cognition or affect, but of voluntary motor control. He returned from Australia to establish the Facilitated Communication Institute (FCI) at Syracuse University, and the North American FC movement was underway.

The Movement Takes Off

Word of FC spread quickly with the help of several media reports of FC “miracles.” The rate of information exchange increased geometrically, feeding the system and driving it forward. FC newsletters, conferences, and support networks contributed to the spread of astonishing success stories, along with examples of prose and poetry attributed to FC authors. The Syracuse FCI began training new facilitators in earnest, in workshops that lasted from a few hours to two or three days. At least two New England universities became satellite programs of the Syracuse FC Institute, as did numerous other private and public agencies that provided training and support for facilitators. Initiates (parents, paraprofessionals, and professionals in several disciplines) were often told that the technique was simple and required no special training. They were urged to train others, and to go out and try FC with disabled individuals. Thousands did. Soon FC was being heralded as a means of “empowering” individuals with severe disabilities to make their own decisions and participate fully in society. FC was rapidly becoming the Politically Correct treatment of choice.

Soon after publication of Biklen’s article, special education personnel and parents around Syracuse, then throughout the U.S. and Canada, adopted FC enthusiastically. Scores of children were placed in regular classrooms doing grade-level academic work with “facilitation.” Decisions about the lives of adults with severe disabilities—living arrangements, medical and other treatments, use of hearing aids, and so on—were based on “facilitated” messages without any attempt to verify authorship objectively. In many cases FC supplanted other communication modes, including vocal speech and augmentative communication systems, that do not require another person for message creation. Some psychologists, speech pathologists and others began giving I.Q. and other standardized tests with “facilitation,” changing diagnoses and program recommendations in accordance with the “facilitated” results. Suddenly “retarded” individuals were proclaimed to have average or above-average intelligence. “Facilitated” counseling and psychotherapy were promoted to help FC users deal with personal problems. Colleges and universities offered courses on FC. Millions of tax dollars were invested in promoting its widespread adoption, with little objective evaluation of its validity or efficacy.

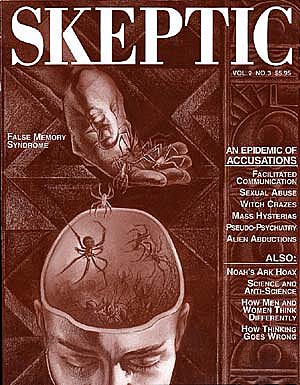

Facilitated Communication requires the “facilitating” hand of the therapist and an alphabet board. The board can be a simple sheet of paper taped to a wall, or it can be a sophisticated electronic keyboard that produces a taped record of the responses.

Enter Psi, Exit Science

Not surprisingly, the experience of accomplishing a breakthrough and being part of a movement was a heady experience for many facilitators. Some, however, reported wondering all along whether the words being produced through FC were really coming from their disabled partners. Others who had serious doubts about the method from the outset found themselves under considerable pressure from parents, peers, and employers to adopt the method wholesale and without question. Reports that facilitators’ private thoughts were being expressed through FC led some to conclude that individuals with autism must have telepathy—a view espoused by a professor of special education at the University of Wisconsin, among others.

FC has an almost irresistible appeal for parents, teachers, and other caring persons who struggle mightily to understand and communicate with individuals who often do not respond or communicate in return.

Facilitators were also imbued, explicitly and implicitly, with a strong ideology that presents dilemmas for many who want to know who is really communicating in FC. Some components of the ideology include:

- Assume competence.

- Don’t test.

- Prevent errors.

- Expect remarkable revelations in the form of hidden skills as well as sensitive personal information.

- Use circumstantial, subjective data to validate authorship.

- Avoid objective scrutiny.

- Emphasize “facilitated” over spoken or other communications.

Contradictory evidence from the controlled evaluations that had been conducted in Australia and those that emerged later in the U.S. were mentioned rarely, if at all, in FC training materials and newsletters. When that evidence was mentioned it was to criticize the evaluation methods and the people who employed them, and to explain away the results by saying essentially that FC could not be tested. In short, FC’s validity was to be accepted largely on faith. With this, science was abandoned.

Concurrently Biklen, Crossley, and their colleagues published further reports of qualitative studies suggesting that FC was highly effective in eliciting unexpected literacy skills from large proportions of individuals with severe autism, mental retardation, and other disorders. Many of these individuals had received little instruction in reading and spelling, or if instruction had been attempted many had not appeared to learn very much. How, then, had they developed age-level or even precocious literacy skills? According to Biklen they acquired these skills from watching television, seeing their siblings do homework, and simply being exposed to words pervading the environment. Or perhaps some had actually been learning from instruction all along, but because their speech was limited they could not demonstrate what they learned.

Facilitated Communication requires the “facilitating” hand of the therapist and an alphabet board. The board can be a simple sheet of paper taped to a wall, or it can be a sophisticated electronic keyboard that produces a taped record of the responses.

How did they verify their claims? Biklen and his colleagues used participant observation and other methods employed by anthropologists, sociologists, and educators in field studies of cultures and social systems. The research was strictly descriptive, not experimental, and employed no objective measurement or procedures to minimize observer bias. Despite their acknowledgement of the real possibility of facilitator influence in FC, these studies did not control that critical variable.

Late in 1991 a few parents of students at the New England Center for Autism, where I serve as Director of Research, began pressing our program to adopt FC. They asked us to make rather drastic changes in their childrens’ lives on the assumption that messages produced with FC represented the childrens’ true wishes and competencies. Some were angry when we decided instead to use it only under conditions of a small-scale experimental study employing the kind of objective evaluation methods that we try to apply to all techniques. At that time we could find nothing about FC in the research literature, so we consulted respected colleagues around the country. Some (in California, surprisingly enough) had not heard of it yet. Others invoked a Ouija board analogy or Clever Hans effect, and suggested that FC would be a short-lived fad. None knew of any objective evidence about FC. To our chagrin, we also encountered individuals with scientific training who were promoting the use of FC without considering the fundamental question about authorship.

The Sexual Abuse Component

The real possibility that “facilitated” words were those of the facilitators was not a cause for much concern as long as the process seemed benevolent. Few wished to throw a wet blanket on the euphoria created by reports of a breakthrough. But almost from the beginning, strange things began to happen: Some FC messages said—or were interpreted by facilitators to say—that disabled FC users had been abused by family members or caregivers. Often the abuse alleged was sexual, and many allegations contained extensive, explicit, pornographic details.

These early studies suggested that FC was susceptible to a somewhat unusual kind of abuse: Allowing others to impose their own wishes, fears, hopes, and agendas on nonspeaking individuals.

So many social movements have a sexual component in them, and FC is not different. Production of sex abuse allegations usually set in motion an inexorable chain of events. Beliefs about FC, the complexities inherent in the method, and the fact that the alleged victim may be seen as particularly vulnerable because he or she is disabled, now began to interact with the zealous pursuit that seems to typify investigations of sex abuse allegations. School or program administrators were notified, who in turn called in representatives of social services and law enforcement agencies. If the accused was a family member with whom the FC user resided, that person was either required to leave the home or the FC user was placed in foster care. If a parent was accused, both parents often faced criminal charges, one for perpetrating the alleged abuse, the other for knowing about it and failing to act. Often actions were initiated by social service workers to terminate parental custody or guardianship. If the accused was a school or program employee, they may have been suspended from their job or even fired. A long and trying ordeal was virtually guaranteed for all involved. An investigation began. Police interrogated the accused, and questioned the alleged victim through their facilitator. Other evidence was sought in the results of medical and psychological examinations of the alleged victim, and interviews with others who may have had information about the alleged events. A presumably independent facilitator was sometimes called in to try to corroborate the allegation, introducing another complexity: There appear to be no established safeguards or objective criteria for ensuring that independent facilitators in fact have no access to information about cases, nor for deciding what constitutes corroborating “facilitated” content.

False allegations have devastating emotional and financial effects on the accused and their families, but leaving individuals in situations in which they may be abused jeopardizes their physical and emotional welfare. It would seem that extreme caution and stringent rules of evidence should apply. A number of cases have arisen in which the only evidence was a “facilitated” allegation, although there have also been reports of cases in which corroborating evidence or confessions were obtained. When an allegation is made through FC, two separate but related questions must be addressed: Who made the allegation, and did the alleged events actually occur? Some courts and investigative bodies in Australia, the U.S., and Canada have decided that the first question must be answered by controlled testing of FC under conditions where independent observers can verify when the facilitator does and does not have information necessary to produce communications. If the FC user does not convey information accurately and reliably under those conditions, and there is no other solid evidence, the legal action is usually terminated. That has been the outcome of testing in every case of which I am aware, but by the time that determination has been made the accused have been traumatized for the better part of a year and have spent tens of thousands of dollars defending themselves. Solid corroborating evidence would certainly answer the second question—whether abuse occurred—but it does not follow logically that it answers the question about who authored the “facilitated” allegation.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t until a number of false “facilitated” allegations of sexual abuse came to light that FC began to be scrutinized closely. As issues about the validity and reliability of FC were addressed in courtrooms all over the U.S., critical and questioning stories appeared in the print and electronic media. Concurrently (though somewhat slowly), results from a rapidly growing number of controlled evaluations began to be disseminated, and a few more skeptical voices were raised.

How To Test FC

The rationale for conducting controlled observations to determine authorship in FC is straightforward: If the disabled FC user is actually the source of the messages, then accurate and appropriate messages should be produced on virtually every opportunity when the facilitator has no knowledge of the expected message. Some controlled evaluations of FC have been mandated by legal questions like those just described, but a number were carried out by clinicians, researchers, and program administrators who simply wanted an objective empirical basis for making decisions about FC. Even James “The Amazing” Randi was consulted in the early stages of testing, some calling him in to make sure fraud and trickery was not involved, others because they genuinely wondered if psychic power was the cause. Randi’s skepticism of the phenomenon was not welcomed by FC supporters. The first major American study was conducted by psychologist Douglas Wheeler and colleagues at the O.D. Heck Developmental Center in Schenectady, NY, who wanted objective evidence to convince skeptics that FC was valid.

Reports that facilitators’ private thoughts were being expressed through FC led some to conclude that individuals with autism must have telepathy.

How do you do a controlled study of FC? Recently I analyzed reports of 17 evaluations of FC that have appeared or have been accepted for publication in peer-reviewed professional journals, and eight presented at scientific conferences. The common and critical ingredients were:

- Consent for participation.

- Objective measures, i.e., use of independent, nonparticipating observers or judges, “blind” to the conditions in effect, who recorded data and/or evaluated the accuracy of FC output.

- Maintenance of physical and emotional support by the facilitator.

- With only a few exceptions, facilitator/FC user dyads who had been working together with apparent success for a considerable period before formal evaluations were conducted.

- Familiar, common communication contexts (e.g., typical academic and language-development activities, discussing everyday events, naming or describing familiar pictures or objects).

- Establishment of apparently successful FC in the evaluation context.

- Control of information available to the facilitator.

The necessary control was established in a number of ways. In some studies, facilitators were simply asked to look at their partner and not the letter display, or were actually screened from the letter display. These kinds of tests were suggested by the observation that many facilitators focus intently on the letters while their partners look at the letters infrequently, if at all. Others presented visual stimuli like pictures, objects, or printed materials only to the FC user while the facilitator was screened from seeing them. Alternatively, spoken questions were presented only to the FC user while their facilitator wore earplugs or headphones playing masking noise. Several evaluations used a procedure described as “message passing:” FC users were engaged in some familiar activities in the absence of facilitators, who then used FC to solicit descriptions of the activities. A couple of evaluations involved independent facilitators, unfamiliar with the FC user, who solicited information that was presumably unknown to the facilitator (e.g., the FC user’s favorite food, a recent event in their life, names of family members, etc.).

The Results

The most telling evaluations used double-blind procedures, in which facilitators and their partners saw or heard different items on some trials, and the same item on other trials. Neither could tell what information their partner was receiving. Responses that corresponded to information presented to the facilitator and not to their partner provided direct evidence that facilitators were controlling those FC productions. Multiple tasks and control procedures were used by several investigators. Facilitators in all evaluations had been trained by leading proponents of FC, or by others who had had such training. They seemed representative of the general population of facilitators, including parents, paraprofessionals, teachers, speech pathologists, and other human service workers. The sample of FC users in these evaluations also appeared representative, comprising a total of 194 children and adults with autism, mental retardation, cerebral palsy, and related disorders.

None of these controlled evaluations produced compelling evidence that FC enabled individuals with disabilities to demonstrate unexpected literacy and communication skills, free of the facilitator’s influence. Many messages were produced over numerous trials and sessions, but the vast majority were accurate and appropriate to context only when the facilitator knew what was to be produced. The strong inference is that facilitators authored most messages, although most reported that they were unaware of doing so. Sixteen evaluations found no evidence whatsoever of valid productions. A total of 23 individuals with various disabilities in nine different evaluations made accurate responses on some occasions when their facilitators did not know the answers, but most of those productions were commensurate with or less advanced than the individuals’ documented skills without FC. That is, they were primarily single words and an occasional short phrase, produced on some trials by individuals whose vocal or signed communication exceeded that level, some of whom had documented reading skills before they were introduced to FC. For most of these individuals, there was clear evidence that on many other trials their facilitators controlled the productions. The controlled evaluations also demonstrated that most facilitators simply could not tell when and how much they were cueing their partners, emphasizing the importance of systematic, controlled observations for identifying the source of “facilitated” messages. The legal, ethical, and practical implications of these findings are obvious and serious. Together with the legal cases and critical media reports, they have made it a little more acceptable to voice skepticism about FC.

The Proponents Respond: Parallels With Psychics

Proponents of FC have criticized the controlled evaluations on several counts. The parallels of their responses to those received by James Randi when he tests psychics are startling. FC supporters, for example, argue that incorrect answers were due to lack of confidence, anxiety, or resistance on the part of FC users, who “freeze up” or become offended when challenged to prove their competence. Likewise, psychics claim they cannot perform in front of video cameras or in the presence of skeptics who make them anxious. In the case of FC, if this were true—if testing per se destroyed the FC process—participants in the controlled evaluations would not have responded at all, or would have produced inaccurate responses throughout, not just when their facilitators did not know the answers. Instead, many accurate words, descriptions, and other responses were produced, but for the most part only when facilitators knew what they were supposed to be.

Additionally, many evaluations took place in familiar surroundings in which individuals had engaged in FC for numerous sessions, with their regular facilitators and letter displays. Sessions typically were not conducted or were terminated if there were any signs of distress or unwillingness to continue. Few refusals were reported. Participants in most evaluations completed numerous trials and sessions over extended periods of time. Most appeared cooperative, even enthusiastic, throughout. Several evaluations were conducted in the context of typical FC sessions, using the same types of materials and questions to which participants had appeared to respond successfully. Questions were no more confrontational or intrusive (perhaps less so) than those often asked in regular FC sessions; in fact, many tasks were identical to those recommended for FC training, except that conditions were arranged so that facilitators could not know all the expected responses. Finally, if FC users simply become too anxious to communicate when challenged, one has to wonder how they are managing to perform in regular academic classrooms, on I.Q. and other tests, in front of TV cameras, and before large audiences at FC meetings. And how can they give “facilitated” testimony, under questioning by judges and attorneys (which is anxiety producing for anyone), as prosecutors in some sexual abuse allegation cases are now arguing is their right?

Another criticism of the controlled evaluations is that the facilitators were not familiar with their partners, were inadequately trained, or did not provide appropriate “facilitation.” That is simply not true. As indicated in the summary above, the FC users’ preferred facilitators participated with them in most evaluations. The only exceptions were two studies that assessed initial responsiveness to FC with facilitators and FC users who were “beginners” when the evaluation started, and a couple of legal cases in which unfamiliar facilitators were involved (who nonetheless “facilitated” successfully with the FC users before controlled testing began). Many facilitators were trained by leading proponents of FC. Most were encouraged to provide whatever physical and emotional support they wished during the evaluation. If they were not “facilitating” properly, few understandable communications would have been produced. Quite the opposite was true. There is a peculiar irony in this criticism, however, since proponents offer no specific guidelines or standards as to what constitutes sufficient training and experience for facilitators. Some facilitators have started using the method after reading an article, watching a videotape, or attending a brief workshop. When we began to take a look at FC at the New England Center for Autism, for example, our three speech-language pathologists were trained by Biklen in a two-day workshop. That appeared to be the norm at that time (late 1991). A further contradiction is that there are reports throughout the descriptive literature on FC that facilitators who were complete strangers had some individuals with severe disabilities “facilitating” sentences (more, in some cases) in their very first session.

Implausibilities and Inconsistencies

An oft-cited criticism of the controlled evaluations is that they required FC users to perform confrontational naming tasks, which proponents consider inappropriate because individuals with autism have global “word-finding” problems. This argument is implausible for several reasons. First, many evaluations did not require FC users to spell specific names; descriptions, copying, multiple-choice options, yes/no responses, and answers to openended questions were just some of the other kinds of responses solicited. Second, there is no solid evidence that such problems are exhibited by individuals with autism. It can be difficult to distinguish words that an individual presumably knows but cannot produce from words that they simply do not know, even with individuals who at one time had well-developed language (e.g., neurologic patients). This would seem to be even more difficult with individuals with autism. Even if this rationalization applied to individuals with autism, what accounts for the results with the many FC users who did not have autism? Additionally, at least three studies documented spontaneous oral naming responses by FC users with autism that were more accurate than their “facilitated” responses. That certainly goes against the “word-finding” hypothesis for those individuals.

In other words, when the data contradict their claims, experiments are not valid; when the data support their claims, experiments are useful.

Some FC proponents attribute negative findings to the supposition that most FC users are not experienced with the kinds of tasks presented to them in the controlled tests. This criticism is especially puzzling. By law, the skills of individuals with special needs must be evaluated on a regular basis, so most FC users have probably had a great deal of test experience. The tasks used in most controlled evaluations were like those used to teach and test academic and language skills in classrooms and training programs everywhere. In fact, many were precisely the kinds of activities that are recommended for FC training, on which the FC users in the controlled evaluations had been reported to perform very well. Again, if inexperience with the tasks were a plausible explanation, FC users should perform equally poorly when their facilitators did and did not know the expected answers. That was not the case in the controlled evaluations.

Finally, FC proponents are inconsistent in claiming that controlled testing undermines the FC user’s confidence, while in the next breath they are quick to tout reports that some attempts at controlled evaluations have produced evidence of FC’s validity. In other words, when the data contradict their claims, experiments are not valid; when the data support their claims, experiments are useful. A report from Australia (referred to as the IDRP report) said that three individuals with disabilities succeeded in “facilitating” the name of a gift they were given in the absence of their facilitators, but one was said to type his responses independently, without FC. The report provided no background information about the individuals, no details about the procedures, and described only one controlled trial completed by each individual. Another exercise described in a letter to the editor of a speech disorders journal claimed that four of five students thought to have severe language delays performed remarkably better with FC than without on a test of matching pictures to spoken words. The facilitator wore headphones but was not screened visually from the nearby examiner who was speaking the words, and no expressive communication was required of the FC users. At best, these exercises must be considered inconclusive, but they have been cited widely by proponents as scientific validations of FC. The contradiction inherent in arguing that controlled testing interferes with FC while endorsing exercises like these seems lost on them. The clear implication is that tests that appear to produce evidence supporting beliefs about FC are good, and tests that fail to do so are bad.

Silent Skeptics

If FC is so obviously not the mental miracle supporters claim it is, why does the movement continue to grow? Why hasn’t the scientific community made a significant public statement against FC? A number of variables probably account for the initial and continuing reluctance of many skeptics to speak up. First, scientists in general are cautious about drawing conclusions without data. When FC first hit the disability community in North America, there were no objective data to be had. A rejoinder to Biklen’s first report by Australian psychologists Robert Cummins and Margot Prior was submitted to the Harvard Educational Review early in 1991. Their paper summarized the results of controlled tests of the validity of FC and the legal and ethical problems it had engendered in Australia. It was not published until late summer 1992, and by that time the FC movement already had considerable momentum. Even then, many skeptics withheld judgment on the basis that the Australian data were limited. This was essentially our reasoning at the New England Center for Autism—that some individuals with autism might write or type better than they could speak (we knew a few), and that if there were some merit to the claims about FC, it would be revealed through careful research using objective methodology.

At the same time, however, we sensed something ominous in the rapidity and zeal with which FC was being applied, the resistance to critical scrutiny, and the antiscience stance of many adherents. Even as the dark side of the FC story began to unfold, relatively few in developmental disabilities who knew how to test the claims about FC experimentally wanted to get involved, perhaps thinking that the best response was to continue to do sound research in their own areas. Others did not to want to be seen as naysayers or debunkers.

Cummins and Prior, both with long histories of involvement in treatment and research in developmental disabilities, were among the first in Victoria to go public with their concerns about FC. Their expressions of skepticism and calls for caution were met with hostility and personal attacks from FC proponents in Australia, a scenario that has repeated itself in the U.S. That suggests another variable, in my opinion one of the most potent: It was (is) not Politically Correct in many circles to suggest that FC might not be all it appears, or even to call for objective evaluation to determine if it is. Those who do are likely to be labelled heretics, oppressors of the disabled, inhumane, negative, jealous of others’ discoveries, “dinosaurs” who cannot accept new ideas, and out for financial gain.

The FC Future

Needless to say, considerable attention and acclaim have accrued to the leaders of the FC movement, but as the data and the harms have mounted, so has the criticism. Recent months have seen a marked shift in media coverage from the glowing reports of miracles that made almost no mention of objective evidence (e.g., PrimeTime Live) to stories about families for whom FC has been anything but a miracle. A documentary on the PBS investigative news program, Frontline, honed in on the implausibility and lack of empirical support for Biklen’s initial claims, along with the emerging evidence from experimental evaluations showing overwhelmingly that most FC is facilitator communication.

The public position of Syracuse University officials appears to be that Professor Biklen’s notions are simply provoking the furor and resistance that all radical new ideas encounter. Perhaps that is the case; time and objective data will tell. Time will most certainly be required for the legal system to do its part in determining the future of the FC movement. A number of cases involving “facilitated” sexual abuse allegations are in process at this writing. To my knowledge, there has been one conviction so far. Several individuals and families who have been cleared of false allegations have filed damage countersuits against the facilitators, school and program administrators, and social service agencies involved. On January 10, 1994 a civil suit was filed in federal District Court for the northern district of New York seeking $10 million in damages on behalf of a family who were among the first victims of FC allegations in the U.S. Among the ten defendants are Douglas Biklen and Syracuse University.

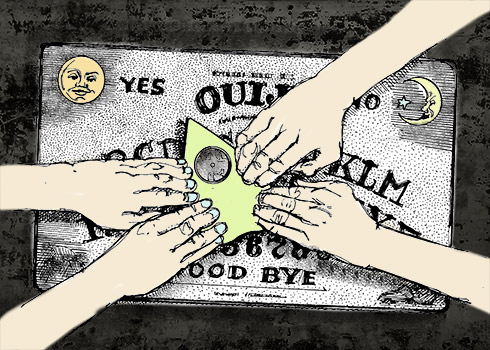

Are there parallels between the ideomotor responses that direct dowsing sticks and the Ouija board and the response of the autistic subjects to the touch of their facilitators?

Finally, if FC is not a mental miracle, is it sleight of hand? By this I do not mean there is intentional deceit on the part of the facilitators. Far from it. Most are genuine, honest, caring individuals who wish the best for their charges. Herein lies an explanation. The power of a belief system to direct thought and action is overwhelming. A full and complete explanation for the FC phenomenon is still forthcoming, but clearly there are parallels with the ideomotor responses that direct dowsing sticks and the Ouija board. As the facilitator gently directs the hand to begin typing, letters are formed into words and words into sentences. Just as with the Ouija board where elaborate thoughts seem to be generated out of thin air while both parties consciously try not to move the piece across the board, the facilitators do not appear to be conscious that it is them generating the communication. Even with the autistic child looking elsewhere, or not looking at all (eyes closed), the hand is still rapidly pecking out letters as if it were a miracle. Unfortunately there are no miracles in mental health. All of us wish FC were true, but the facts simply do not allow scientists and critical thinkers to replace knowledge with wish. ![]()

Bibliography

- Biklen, D. (1990) “Communication Unbound: Autism and Praxis.” Harvard Educational Review, 60, 291–315.

- Biklen, D. (1992). “Autism orthodoxy versus free speech: A reply to Cummins and Prior.” Harvard Educational Review, 62, 242–256.

- Biklen, D. (1993). Communication Unbound: How facilitated communication is challenging traditional views of autism and ability/disability. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Crossley, R. (1992a). “Lending a hand: A personal account of the development of Facilitated Communication Training.” American Journal of Speech and Language Pathology, May, 15 18.

- Crossley, R. (1992b). “Getting the words out: Case studies in facilitated communication training.” Topics in Language Disorders, 12, 46–59.

- Cummins, R.A., & Prior, M.P. (1992). “Autism and assisted communication: A response to Biklen.” Harvard Educational Review, 62, 228–241.

- Dillon, K.M. (1993). “Facilitated Communication, autism, and ouija.” Skeptical Inquirer, 17, 281–287.

- Green, G. (forthcoming). “The quality of the evidence.” In H.C. Shane (Ed.), The clinical and social phenomenon of Facilitated Communication. San Diego: Singular Press.

- Green, G. (1993). Response to “What is the balance of proof for or against Facilitated Communication?” AAMR News & Notes, 6 (3), 5.

- Green, G., & Shane, H.C. (1993). “Facilitated Communication: The claims vs. the evidence.” Harvard Mental Health Letter, 10, 4–5.

- Hudson, A. (in press). Disability and facilitated communication: A critique. In T.H. Ollendick & R.J. Prinz (Eds.), Advances in Clinical Child Psychology (Vol. 17), New York: Plenum Press.

- Jacobson, J.W., Eberlin, M., Mulick, J.A., Schwartz, A.A., Szempruch, J., & Wheeler, D.L. (in press). “Autism and Facilitated Communication: Future directions.” In J.L. Matson (Ed., ), Autism: Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. DeKalb, IL: Sycamore Press.

- Jacobson, J.W., & Mulick, J.A. (1992). “Speak for yourself, or…I can’t quite put my finger on it!” Psychology in Mental Retardation and Developmental disabilities, 17, 3–7.

- Mulick, J.A., Jacobson, J.W., & Kobe, R.H. (1993). “Anguished silence and helping hands: Miracles in autism with Facilitated Communication.” Skeptical Inquirer, 17, 270–280.

About the Author

Dr. Gina Green is Director of Research at the New England Center for Autism and Associate Scientist in the Behavioral Sciences Division of the E.K. Shriver Center for Mental Retardation, both in Massachusetts. Her doctorate is in the experimental analysis of behavior from the psychology department at Utah State University. She is presently also Clinical Assistant Professor in the College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences at Northeastern University in Boston. Among her many publications Dr. Green has written extensively on facilitated communication and is one of the first to submit the phenomenon to rigorous experimental testing. She is presently working on a chapter entitled “The Quality of the Evidence,” for a book edited by Dr. Howard Shane, on The Clinical and Social Phenomenon of Facilitated Communication.

This article was published on August 17, 2016.

“Annie’s Coming Out” was the First Book I read about facilitated communication. It was so full of inconsistencies and leaps of faith I could not believe that anyone would take it seriously — and apparently they still do!

https://www.amazon.com/Annies-Coming-Out-Rosemary-Crossley/dp/0140056882

Biggest howler — a girl seriously affected with Cerebral Palsy, in a home since three years old, considered as one of the ‘bean bag” children, and cared for by Yugoslav women with little to no command of English, able to read and spell English? And she knew about “Mothering Sunday”– except that she mixed it up with Mother’s Day :-(

“Individuals with “severe communication impairments” (e.g., severe mental retardation, autism) are assisted in spelling words by “facilitators” (teachers or parents) who provide physical support, most often (at least initially) by holding their hand, wrist, or forearm while they point to letters on a keyboard or printed letter display. ”

Two suggestions:

1. Why does the facilitator have to be human? Robotic or mechanical “facilitators” can “provide physical support”, as with para- and quadra- pelegics.

2. If the experiment uses a human facilitator, why one who understands English, the language of all the trials and experiments above.

Had read this and was about to delete it, but then I remembered I saved it to see how it was treated on the web.

ASHA: “It is the position of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) that the scientific validity and reliability of facilitated communication have not been demonstrated to date. Information obtained through or based on facilitated communication should not form the sole basis for making any diagnostic or treatment decisions.”

Wiki: “[…]is a discredited technique used by some caregivers and educators in an attempt to assist people with severe[…]”

Mixed…

Isn’t it amazing how many pseudo sciences seem to abound as soon as the proponents thereof realize how much money can be made out of it.

Of course validation thereof or anything else that could interrupt the rapid flow of money into the ‘organization’ is anathema.

Promoters of FC passed around anecdotes and results of tests that could not possibly determine whether it works, and scrupulously avoided putting it to the test in the only and obvious way to do so. And when finally such a test came out negative, they brought out the same catechism of excuses that ESP advocates use, all of which are essentially lies .

” Just as with the Ouija board where elaborate thoughts seem to be generated out of thin air while both parties consciously try not to move the piece across the board, the facilitators do not appear to be conscious that it is them generating the communication.”

We should certainly HOPE that the “Facilitators” are sincere even if deluded in their naive beliefs..

Using disabled people as fake instruments for dishonest mantic practices should be in the Catholic List of

“sins that cry to heaven for vengeance”

Bob Pease

“Bilkin & his colleagues used participant observation and other methods employed by anthropologists, sociologists & educators in the field studies of cultures & social systems. The research was strictly descriptive, not experimental, and employed no objective measurement or procedures to minimize observer bias.”

I read the above sentences several times. Then I looked up “participant observation” on the UC Davis website. http://psc.dss.ucdavis.edu/sommerb/sommerdemo/observation/partic.htm

Apparently the researcher joins some sort of social structure as an “insider” – mental patient, waitress, mushroom harvester – and reports on what they see.

This seems a remarkably unsuitable technique for determining whether FC could possibly work, since the question is about which mind the communication is coming from, which is not apparent from observing from the outside, and which the facilitators claim is not coming from them. The description of how FC was “studied” also calls to my mind the old skeptical saying, “The plural of anecdote is not data”.

If one wanted to see if there’s anything worth studying, I would start by comparing the products of FC with: 1. known writing samples of the “facilitator”, and 2. with communications known to have been generated by autistic persons.

But the thing that makes me most suspicious is the claim that FC unlocks autistic persons’ communication with a “special” form of touch. Autistic persons are kind of famous for not liking to be touched.

Trying to enlighten the hopeful consumers of FC might be similar to giving our skeptical opinion of Alcor Life Extension Foundation. As long as it is their own money, this is fine. If we are talking about government subsidies, that is when skepticism ought to kick in.

No Mary it is not fine when people use their own money to ‘facilitate’ charges of sexual abuse and other nonsense. Skepticism should ALWAYS be applied, not just when government money is involved.

An excellent piece, thank you very much. But I have to take exception to the opening line: “The cliché that ‘there is nothing new under the sun’…” This is a quotation from the Bible, the book of Ecclesiastes. Calling it a cliché trivializes the timeless truth it expresses.

Wonderfully exposed in a 1995 episode of TV’s “Law and Order,” titled “Cruel and Unusual”.

I immediately thought of that episode, too. It was really well done.

Sadly, there are Law & Order (& SVU & Criminal Intent) episodes that present quack psychology as accepted science. I’m thinking of examples like Police Psychologist Liz Olivette saying that trauma causes memories to be repressed and come out later, MPD depicted as a real and uncontroversial phenomenon in an episode about a waitress who also appears to be a guy named “Bobby”, and multiple episodes about “battered wife/battered spouse syndrome”.

I have often heard that traumatic memories cannot be repressed. but that is not true. If a child is required or instructed to “forget this, it never happened”, he can absolutely do that, and remember said incident later in life.

“And remembered later in life.”

And what brings these memories back, because if it is humorist or “regression therapy” or just a careless psychologist – they may not be real memories at all.