Drug overdose is now the leading cause of death for Americans under the age of 50 and has lowered the average life expectancy in the United States.1 Over the next decade as many as half-a-million people in the United States will die from opioid substances that include heroin, pain-killers such as morphine and oxycodone, and synthetic agents such as fentanyl.2

Public policy to date has failed to counter this epidemic. Standing in the way of effective response are three mistaken approaches to the problem:

- Misinterpreting correlation as causation.

- Misunderstanding the physiology of addiction.

- Overlooking the social psychology of addiction.

Mistake #1: Misinterpreting Correlation as Causation

Does epidemic opioid overuse result from too many prescriptions of medication for pain relief? In March of 2018 President Trump announced that his administration is “taking action to prevent addiction by addressing the problem of overprescribing…. We’re going to cut nationwide opioid prescriptions by one-third over the next three years.”3 The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also attribute the overuse of opioids and other addictive substances to prescription practices:

Drug overdose deaths in the United States more than tripled from 1999 to 2015. The current epidemic of drug overdoses began in the 1990s, driven by increasing deaths from prescription opioids that paralleled a dramatic increase in the prescribing of such drugs for chronic pain…. The problem with misuse of prescription drugs of various kinds is related to high levels of prescribing of such medications.4

This concern about excessive prescription is certainly legitimate. However, a close look at the historical data clarifies the causal role that prescription plays in the opioid epidemic.

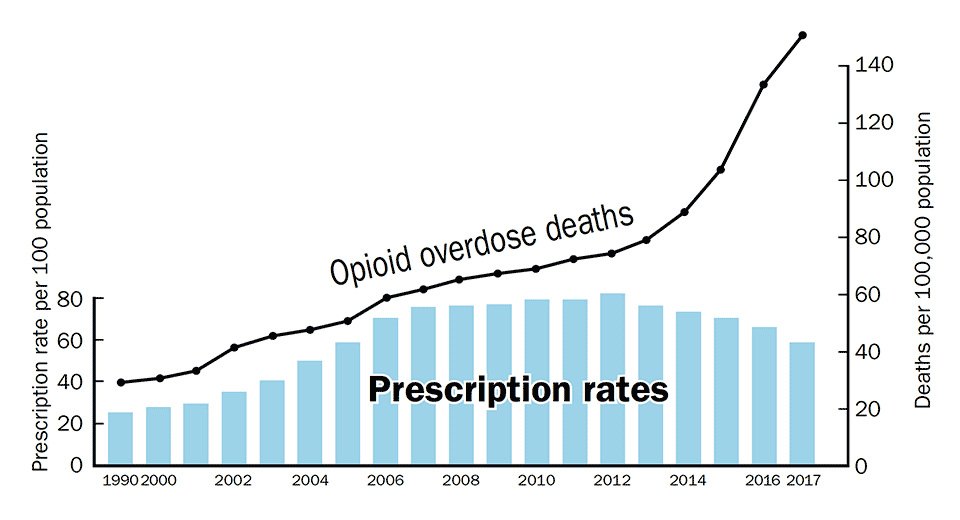

Opioid Prescription Rates and Opioid Overdose Deaths, 1999–2017. Graph constructed from CDC data.5

The years of the steepest increase in overuse fatalities, 2012 to 2017, are also years in which prescription rates declined. This divergence between fatality and prescription rate trends is striking, even when we take into account that it might require several years for a lower prescription rate to result in significantly fewer overdose deaths. The sharp rise in recent years of opoid-induced deaths is in fact due to the consumption of drugs that are rarely used for medical pain management: As of 2015 the rate of overdose deaths due to illegally obtained heroin and synthetic opioids had gone up so much that they took more lives than did all of the other prescribed opioids combined.6 Synthetic opioids like fentanyl (a drug 50 times more potent than heroin) and carfentanil (5000 times more potent than heroin) are inexpensive to produce and easily shipped to customers through the mail. Moreover, heroin and other street drugs are often mixed with fentanyl and its derivatives, further raising fatal overdose rates.

Even during the years 1999–2012, when opioid prescriptions and overuse mortality rose in tandem, this correlation does not show that the first was a major cause of the second — the addiction rate among patients taking opioid medication for chronic pain is in fact quite low, less than 8 percent.7 Over the past two decades, U.S. states have enacted a number of prescription-control laws, most targeting opioid drugs. However, this legislation has had a very limited impact on the rate of overdose fatalities.8 The correlation between prescription and overuse of opioids is no more causative than any number of treatment-illness relationships. Surgery, for example, typically makes a patient more susceptible to infection — a fact that supports more attention to sanitizing operating environments, but doesn’t justify a reduction in the number of surgeries.9 Similarly, taking birth control pills slightly raises a woman’s chances of contracting cervical or breast cancer,10 but this happens sufficiently rarely that it provides little reason to forego this method of contraception.

To be sure, opioids like OxyContin are misleadingly marketed and overprescribed in the United States, and sensible regulation is very much needed. So-called “pill mills” (in which prescribers dispense narcotics without a reasonable medical purpose) should be shut down. Moreover, patients taking opioids for a legitimate medical purpose sometimes provide these drugs to others, including family and friends. Better education and training of health care professionals can improve prescribing practices. For instance, physicians should not prescribe opioids for a longer duration than effective pain management requires, and should consult a prescription drug monitoring database (PDMP) to track patients’ use of controlled substances and prevent “doctor shopping” to obtain multiple prescriptions for the same medical condition. However, the solution that continues to find favor among legislators — enactment of prescription-reduction rules that are insensitive to the complexity of medical pain treatment issues — has proven to be not only largely ineffectual but also medically unjustified; the consequence of too strict prescription requirements is the abandonment of many patients to their suffering. Deprived by their physicians of the pain relief afforded by opioids, they are motivated to look for a solution elsewhere. Commenting in March 2018 on the under-treatment of patients in pain, Jianguo Cheng, President of the American Academy of Pain Medicine, noted “There are many pain clinics flooded with patients who have been treated previously by their primary care physician.”11 While it is true that non-opioid pain relief remedies exist, and that better ones may be developed in the future, for many patients the most effective help still comes from the standard opioid medications.

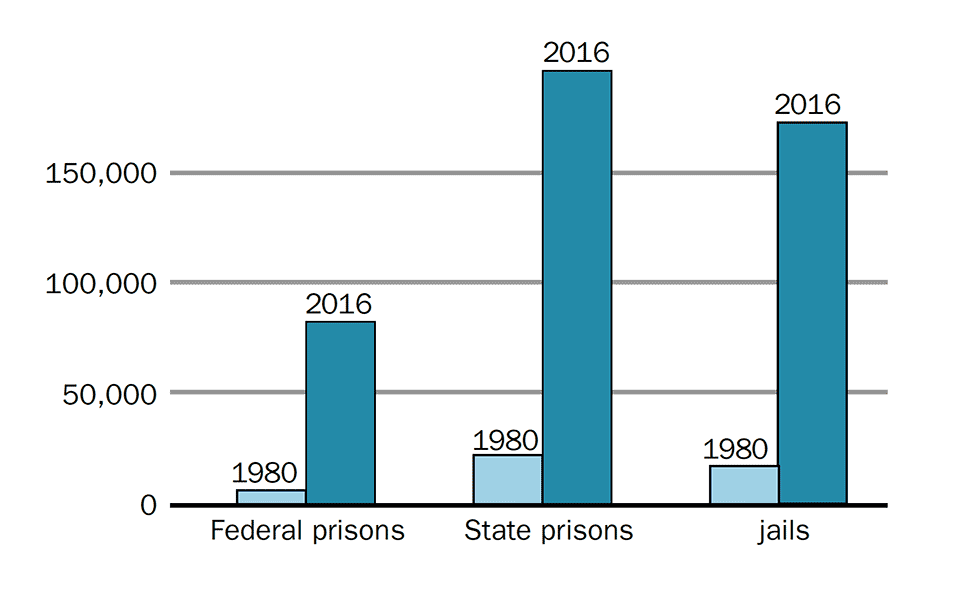

People Incarcerated for Drug Offences 1980 compared to 2016. Severe punishment of drug offenders in the U.S. has increased the prison population without effectively deterring drug related crime.12

Mistake #2: Misunderstanding the Physiology of Addiction

Over the past three decades, the neurobiology of addiction has been investigated down to the molecular level. Although there remains much more to learn, scientific research has illuminated how the consumption of opioids initiates certain neural processes that impact the reasoning and executive functions of the frontal cortex and give rise to addictive behaviors. This research has been given a popular, if sometimes oversimplified, gloss by the mass media — e.g., former radio host Bill Moyers’ explanation that “drugs hijack the brain.” This account diminishes the role of free will in the choices that addicted individuals make and supports the “supply restriction” approach to drug misuse that still prevails in the United States today. The idea here is to remove access to addictive substances, so that the brain, however susceptible it might be to their appeal, is simply unable to develop or sustain an addictive habit.

The supply restriction approach to substance abuse is certainly an advance beyond the moralistic, often religiously motivated principles that have largely governed U.S. drug policy over the past century. Yet it has a very problematic history. A century ago, Prohibition did reduce the use of alcohol, but that resulted also in a thriving black market, corruption of police, and untreated alcohol-related disease. In 1971 President Richard Nixon inaugurated a nationwide “War on Drugs” to curtail the domestic trade in addictive substances and also launched a massive interdiction campaign to halt import of marijuana from abroad. These efforts were unsuccessful (Colombia replaced Mexico as the major marijuana supplier) as were subsequent attempts on the part of the federal government and border states to curtail drug trafficking.13

These failures of the supply restriction approach do not necessarily dampen the enthusiasm of its advocates. Yes, this strategy works imperfectly, they might concede, but isn’t policy that makes access to addictive substances more difficult and expensive bound to discourage use? Indeed, if drugs hijack the brain, then this common-sense corollary seems to follow: Reduced availability of drugs will result in less hijacking.

However, research on the behavioral and biological dynamics of addiction shows that supply restriction may actually strengthen addictive habits rather than suppress them. “Prediction error” studies done with rats and non-human primates have indicated that addictive urgency is modulated by the nervous system: intermittent, unexpected rewards stimulate the firing of neurons in certain areas of the brain, whereas anticipated rewards leave these same neurons quiescent.14 This dynamic characterizes human addiction too: the thrill of unexpectedly and illicitly obtaining a reward focuses and sharpens desire. Paradoxically, when the supply of an addictive substance becomes risky, intermittent, or limited in some other way — because of a police crackdown, for example — the consequence is sometimes an increase in the craving that holds the addiction in place. This occurs not only in the case of substance misuse but in other human risktaking activities also. Compulsive gambling, for example, is recognized in the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as an addictive disorder. Gambling is similar to drug use in that uncertainty of outcome is apt to reinforce an addictive habit.15

A billboard produced by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health seeking to educate the public about addiction. Their #StateWithoutStigMA website suggests that the stigma of drug abuse may prevent people from seeking treatment, thus holding them back from recovery.

In the United States, reducing the availability of addictive drugs to zero has never been an achievable aim. Even imprisonment often does not result in total abstinence; inmates manage in one way or another to obtain substances that sustain their habit, and indeed, 95 percent of those addicted at the time of incarceration return to drug abuse upon release.16 Deterrence targets someone whose rational assessment of costs and benefits informs behavior. But addiction is characterized by a willingness to suffer extreme loss to maintain a habit — the sacrifice of a satisfactory job, dissolution of a marriage and of friendships, deterioration of physical health, and incarceration. Consequently, the legal restriction of supply has not successfully curbed drug misuse.

Mistake #3: Overlooking the Social Psychology of Addiction

The disease model of addiction, which focuses attention on physiological and genetic factors rather than on social-cultural context, is evidence-based and certainly more humane than the “Just Say No” approach that attributes addiction to a deficit of personal virtue or religious faith. Opioid addiction, like cancer or heart disease, ought not to be regarded as blameworthy and deserving punishment. On the other hand, the disease model can be misleading inasmuch as it suggests that substance misuse is entirely walled off from the will of the afflicted individual.

The difficulty of avoiding or overcoming an addiction varies widely from one person to the next. One individual who has been overusing might experience unbearable anxieties or pain upon discontinuation, while another with a similar history but a different genetic inheritance, for example, might discontinue and experience much less severe symptoms. Many of those who are addicted can succeed in diminishing the harmful consequences of their drug use — and sometimes in halting that use altogether. In the 1960s, about 20 percent of the U.S. soldiers in Vietnam became addicted to heroin, but when they returned home more than 95 percent stopped using the drug. Further, these veterans were able to stay clean provided they did not re-enlist and return to the war.17 Their high rate of recovery is in keeping with subsequent research indicating that addiction can be remedied by a change in environment.18

Animal research also gives some support to this conclusion (although care must be taken when extrapolating from non-human animals19). In 1978, a study that became known as the “Rat Park Experiment”20 took a very unorthodox approach to rodent research. In previous studies carried out in the 1960s and 1970s, solitary rats had been placed in small cages and given access to water containing addictive substances such as morphine or cocaine. The animals soon prioritized consumption of this water and drank enough of it to kill themselves. In the Rat Park Experiment, however, rats inhabited a shared environment consisting of a roomy cage providing many amenities: nooks and crannies that the animals could explore, balls and other toys to play with, and places to hide. In this socialized situation they overwhelmingly preferred ordinary to drug-laced water. Many subsequent studies have confirmed the hypothesis that rodents living collectively under low stress conditions do not become substance-addicted.21

Of course, humans do not inhabit environments as ideal as “Rat Park.” Poverty, social injustice, and racism are present in many communities. White collar professionals as well as blue collar workers often cope with unrewarding, stressful jobs or unemployment. Friendships and marriages fail. Upon release from prison, many of those incarcerated for drug offenses return to the same life conditions that encourage addiction. Some of these circumstances can be transformed, increasing the likelihood of recovery from an addictive habit. For instance, re-integration of former prisoners into a community that welcomes and supports them raises their prospects for living a non-addicted, fulfilling life.22

What Must Be Done

A harm-reduction approach to drug misuse replaces criminalization with programs seeking to make addicts active participants in the process of their own recovery. Substitution of less euphoric drugs such as methadone and buprenorphine for more damaging and deadly heroin and fentanyl, combined with counseling and psychotherapy, helps addicts regain control over their lives. This response to addiction has found wide application in Western European nations since the 1980s. Portugal, for example, decriminalized illicit drug use in 2001 and then funded addiction treatment programs and a public information campaign. Education about drug use became part of the standard Portuguese high-school curriculum. These policies have helped to reduce the country’s per-capita drug mortality rate, which today is about 50 times lower than that of the U.S.23

The reviews you’re reading appeared in Skeptic magazine 24.1 (2019). Buy this issue.

Although a punitive approach to drug overuse continues to misinform policy in the United States, public opinion is changing. Excessive use of opioids is today widely recognized as a problem that affects relatively affluent Americans as well as those living in poverty, and partly for that reason evidence-based treatment approaches are receiving more attention. In 2017 the U.S. Opioid and Drug Abuse Commission acknowledged that in many situations, opioid substitute treatment achieves better outcomes than coerced abstinence.24 The Commission report recommended better training of drug counselors, therapists, and prescribers; use by police and emergency care workers of naloxone that can be injected to reverse overdose and save lives; and more funding for “drug courts” that send addicts to treatment as an alternative to jail. The Commission also gave some attention to the environmental conditions that encourage drug misuse.

Implementation of the Commission’s recommendations depends, however, upon adequate financing, which is uncertain given recent federal cutbacks to Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act, and other health-support programs that provide addiction treatment and recovery services. Nonetheless, we know what must be done to effectively combat the opioid epidemic, and we will succeed if public support is in place. ![]()

About the Author

Dr. Raymond Barglow majored in physics at Caltech and received a doctorate in philosophy at UC Berkeley. He has taught at UC Berkeley and Trinity College and writes on science, ethics, and public policy issues.

References

- Kochanek, K. D. et al. 2017. “Mortality in the United States, 2016.” CDC National Center for Health Statistics, Data Brief 293, December. Kaplan,S. 2017. “C.D.C. Reports a Record Jump in Drug Overdose Deaths Last Year,” New York Times, Nov. 3.

- Blau, M. 2017. “STAT forecast: Opioids could kill nearly 500,000 Americans in the next decade,” June 27. https://bit.ly/2OQVCAY

- White House Briefing. 2018. “Remarks by President Trump on Combatting the Opioid Crisis,” March 19.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2017. “Executive Summary of the Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks and Outcomes, United States.”

- CDC, “Opioid Overdose: Data Over-view.” 2017. https://bit.ly /2cfEYuy.Centers for Disease, “U.S. Prescribing Rate Maps.” https://bit.ly/2vzRjoj

- National Center for Health Statisics. 2017. “Data Brief 294. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2016.” https://bit.ly/2EPK2Bo

- Volkow, N.D and McLellan, A. 2016. “Opioid Abuse in Chronic Pain — Misconceptions and Mitigation Strategies.” New England Journal of Medicine, March 31. https://bit.ly/2wReXfa. Minozzi S. et al. 2012. “Development of Dependence Following Treatment with Opioid Analgesics for Pain Relief: a Systematic Review.” Addiction, April. https://bit.ly/2qTp0wE

- See for example, this report from Florida: “Florida Department of Law Enforcement Medical Examiners Commission Annual Drug Report.” 2017, 1–64.

- Berrios-Torres, S et al. 2017. “Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection.” JAMA Surgery, August. https://bit.ly/2DztFtl

- National Cancer Institute. 2018. “Oral Contraceptives and Cancer Risk.” https://bit.ly/2zhiuo5

- Sullum, J. 2018. “The Intensifying Conflict Between Opioid Control and Pain Control.” Practical Pain Management, March 4. https://bit.ly/2zg4iMg

- Data source: “Criminal Justice Facts.” 2017. The Sentencing Project. Washington, D.C.

- Schultz G. and Aspe, P. 2017. “The Failed War on Drugs.” New York Times, Dec. 31, 9.

- Schultz W. 2016. “Dopamine Reward Prediction Error Coding.” Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, March. Although prediction error behavior has a neurological basis established over the past three decades, it is a phenomenon that has been observed for longer than that. B.F. Skinner’s research dating back to the 1940s and 1950s showed that when rats were given an intermittent, unpredictable reward, they pushed a lever more persistently than when they received a reward every time. It was easy, those working Skinner’s laboratory found, to attach rats or pigeons to a single behavior in this way, so that the animals no longer cared about anything else. Researchers also found that responses reinforced intermittently took longer to extinguish than responses that were always reinforced.

- Neuroscience journalist Maia Szalavitz cites and summarizes scientific findings about gambling and other forms of addiction in Szalavitz, M. 2016. “Addicted to Anticipation.” Nautilus, September 15. https://bit.ly/2BhTMFA

- National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence. 2015. “Alcohol, Drugs, and Crime.” https://bit.ly/25Bq717

- The research team that came up with these results was led by psychiatric epidemiologist Lee Robins, whose study was published in 1973. This study is placed in historical context by Spiegel, A. 2012. “What Vietnam Taught Us About Breaking Bad Habits.” NPR Morning Edition, Jan. 2. https://n.pr/2OSxiyn

- Alexander, B. 2015. “Addiction, Environmental Crisis, and Global Capitalism.” Presentation at the College of Sustainability, Dalhousie University, February 26 and 27. https://bit.ly/2KeX3bv

- Young-Wilson. 2006. “Animal Experiments in Addiction Science.” National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://bit.ly/2A55yS0

- Alexander, B., et al. 1978. “The Effect of Housing and Gender on Morphine Self-Administration in Rats.” Psychopharmacology, July 6, 175–179. Follow-up studies have confirmed the hypothesis that rats living collectively under low-stress conditions turn down consumption of addictive substances.

- Eitan, S. et al. 2017. “Opioid Addiction: Who Are Your Real Friends?” Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 83, 697–712.

- Binswanger, I. 2012. “Return to Drug Use and Overdose after Release From Prison: a qualitative study of risk and protective factors.” Addiction Science and Clinical Practice, March 15. https://bit.ly/2Trdoy8

- Kristof, N. 2017. “How to Win a War on Drugs: Portugal Treats Addiction as a Disease, Not a Crime” New York Times, September 22. https://nyti.ms/ 2yvws3K. Comparison of drug overdose mortality rates in the U.S. with those in European countries may be misleading, however, since the prescription rates in all of them are lower than those in the U.S.

- Christie, Chris et al. 2017. “The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis — Final report.” https://bit.ly/2qUywzD

This article was published on March 27, 2019.

Brad, I would have to repeat that a group of studies that opioids are effective over a duration of 3 months (as you cited) is not evidence that they are effective in 2 years, and the studies I have seen indicate that pain control is no better in those treated with opioids than in those treated with non-narcotic treatment or CBT, with the main difference being that those on opioids are less likely to be working. It is difficult to do a good pain study, as quantifying it is a challenge, and those on opioids will certainly feel worse if they are missed or stopped, but that doesn’t mean that the patient has less pain on the med than if it had never been started. Find me a truly long term article looking at 2 years or more in a controlled fashion, so I can revise my opinion, but the cited document has nothing to do with my contention.

Hello Brad,

Yes, opioids can in some cases alleviate chronic pain quite effectively, and the author of the comment you’re responding to, Dr. Maher, agrees with you on that point.

Thanks for the references you provide. I note, however, that

the research survey you refer to concludes that: “Opioids are efficacious in the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain for up to 3 months in randomized controlled trials.” Addiction resulting from long-term opioid treatment of pain may very well begin after 3 months.

A valuable commentary on this subject is David Leonhardt’s “Opioid Overreaction” published in the NY Times a few days ago: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/29/opinion/opioid-crisis-chronic-pain.html

And see Maia Szalavitz’ recent op-ed in the NY Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/09/opinion/sunday/pain-opioids.html

The link to the Reason Magazine article you’re recommending is incorrect in your posting, because it has a superfluous letter “n” at the end of the URL. The correct link is: https://reason.com/blog/2018/11/29/opioid-related-deaths-keep-rising-as-pai

But this article, like some others published in Reason on this subject, errs in failing to recognize the role that opioid over-prescription has indeed played in the epidemic. Purdue Pharma may not be as villainous as the media makes out, but the company’s marketing of Oxycontin was as unethical as it was hugely profitable.

With regard to Suboxone (buprenorphine), yes, it is an opioid. But medical treatment using an opioid substitute like Suboxone can be a life saver for those trying to cope with and/or cease an addiction.

My wife had severe pain due to multiple fractured joints. Kaiser Permanente (KP) prescribed opioids for four week. Then she was subjected to an intense interview before being granted a refill. Thankfully KP is very careful about opioid prescriptions.

In response to Dr. Maher’s comment:

Mores specifically, in response to your statement: “there is no evidence that narcotics are effective long term for the management of chronic pain, and physicians need to stop using these meds for that purpose.”

To the contrary, there are numerous peer-reviewed, government sanctioned studies indicating opioids are extremely effective for long-term use. Here is a link to some of the studies.

https://cergm.carter-brothers.com/2019/03/09/researcher-publishes-on-the-long-term-benefits-of-opiates-in-chronic-pain/?amp_markup=1&__twitter_impression=true&fbclid=IwAR2-ZDjm4mbuocEgp-ovxiwynVGEaa_QbaH3OErBZGIgIiH5gSMcFrZm6Zk

It is interesting to note that of the 66 references cited in the above-referenced publication, more than 55 of them were published prior to 2016. Meaning this research was openly available to the CDC prior to publishing their clearly biased 2016 Recommendations for Prescription Guidelines. Yet the CDC still incorrectly claims that no research on the long-term use of opiates in chronic pain is available, or that what they did review, was inconclusive. Which is clearly not forthcoming, nor accurate.

It appears the (highly biased) “expert panel” the CDC so carefully hand-selected to review existing literature was anything but. As they intentionally only referenced research that fit their preconceived, anti-opioid agenda.

In addition, the carefully selected “expert panel” for some reason failed to include any physicians with actual hands-on experience working with actual chronic pain patients, and it also didn’t include a single chronic pain patient.

The so-called “expert panel” was primarily populated by addiction physicians (psychiatrists) and Suboxone proponents. Hence, the panel’s foregone conclusions were of little surprise to anyone. They were carefully orchestrated by Andrew Kolodny, et.al., to identify users of opioids as “addicts” and to further promote the use of Suboxone (yet another opioid) to address such addictions.

Here is a link to a similar article demonstrating the same relationship between prescriptions and overdoses:

https://reason.com/blog/2018/11/29/opioid-related-deaths-keep-rising-as-pain

Such studies (there are many more of them) demonstrate clearly how the government is unquestionably using pain physicians and their patients as easy scapegoats in their fictitious (made-up) war on drugs.

I’m going to take a different tack here – the world is already overpopulated. Hence, Rush, have a Rush – I’d even foot the bill.

Darvocet was taken off the shelves in November of 2010 without an efficacious alternative. We need a weak opioid alternative that works that doctors aren’t afraid to prescribe…because opioids work. Also we need to see if other countries restricting codeine to prescription only has any positive impact…if not maybe we should consider codeine OTC like it is in many other countries.

Mr Barglow –

You first addiction rates-over-time vs. perscription-rates graph does not establish anything more than an invitation to conclusion by implied correlation. Fact is, the addiction to the three groups of drugs could sustain the increases for other reasons like experimentation with use and military personnel combat related self-medication outside of prescription issuance.

There could also be foreign powers seeking to undermine our society by flooding in supplies. It could also be due to illegal immigrant usage & addictions brought into the States.

I urge you to be careful.

Thanx for listening.

I’d like to thank everyone for your comments yesterday. Caused me to reconsider a thing or two!

The opioid crisis is multidimensional and doesn’t admit of any simple solution, medical or otherwise, although easier access to treatment is of course essential.

See this op ed in yesterday’s New York Times (March 27): “Want to Reduce Opioid Deaths? Get People the Medications They Need.”

And this article in the Times on Tuesday ( March 26): “Purdue Pharma and Sacklers Reach $270 Million Settlement in Opioid Lawsuit.”

Tzindaro and Steve Williams,

Drug addiction is, as I take both of you to be suggesting, bound up with deep problems that are endemic to our society. I agree 100%.

Your point, Tzindaro, that addiction patterns may differ widely when we look at factors of race and class, is an essential one. Addiction is not just a medical problem!

Steve, your comment about addiction being one behavior in a constellation is important. Rehabilitation must take the whole person into account. Former prisoners who are welcomed back and provided with opportunities to live productive, fulfilling lives do better than those who are released, given $50, and dropped at the side of the road.

Certainly wouldn’t say decriminalizing drugs would fix all social issues, but a lot of crimes committed by addicts are related to the illegality of drugs. If you can’t pass a drug screening you can’t get a lot of jobs. I read “Chasing the Scream” by Johann Hari about 4 years ago. From what I remember, when Portugal de-criminalized a lot of drugs it enabled addicts to hold down jobs and live a fairly normal life. It is one of those books on my re-read list.

I absolutely agree with you. While to my knowledge controlled studies have shown that pain with opioids at 2 years is equivalent to similar patients without opioids, we need a lot more data to generate a conclusion. But there is a difference between dealing with a person who shows up with chronic back pain for a first visit, and someone who has been treated for 5 years with hydrocodone and isn’t having dosage creep or side effects. The biggest problem patients aren’t the second, but others who either start on opioids for what is felt to be acute pain and never get off the drug (something like 20% of ER patients and 17% of surgical patients started on an opioid) or recreational users who are looking for more effect.

Jack Happens,

Yes, the decline in prescription rates over the past 7 years or so could be misleading. The data set on which the graph in the article is based does not make the fine distinctions that you point to. As you say, we need to take into account the possibility of multiple prescriptions for the same person and also the strength and quantity of the prescriptions. The graph does not provide that detail.

It’s very clear, though — and I believe you will agree — that non-prescribed, illegally obtained substances like heroin, fentanyl, and carfentanil have greatly increased the overdose death rate in the United States.

David Burns, I can only say to you: Godspeed! Please see my 2nd reply to Dr. Maher.

I comment in the article about the difficulty some patients have in getting appropriate pain-relieving medication. I wish you the best.

Decriminalization of drug possession/use and treatment options are fine. But we’re also dealing with the other behavior of the addict, the thefts, robberies, assaults, murders, etc. Many of these people will get into the system anyway.

Elaborating my reply to Dr. Maher.

There are certainly a good number of patients who manage their chronic pain successfully by using opioid medication.

Yes, there are often side effects, including tolerance and even hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to pain). But that shouldn’t lead us to generalize and say in every case, “If you’re using an opioid to deal with your chronic pain, that is not a good thing!”

Well, I would guess that you agree with me on this, Dr. Maher. We need to take a nuanced, case-by-case approach to this matter.

Thank you for this very thoughtful comment, Dr. Maher!

I might disagree just a little when you say there is “no evidence that narcotics are effective long term for the management of chronic pain.”

Yes, the research literature indicates that, as you suggest, opioids are not the remedy of first choice for chronic pain and are unlikely to serve this pain-relieving purpose at all well.

At the same time, some overview studies conclude that the case is not entirely closed on this matter. For those who are interested, see:

“Opioids for chronic noncancer pain — A position paper of the American Academy of Neurology”

https://n.neurology.org/content/83/14/1277

and this recent BMJ arcticle: “Where now for opioids in chronic pain?”

https://dtb.bmj.com/content/56/10/118

This article says that “A small proportion of people with long-term pain may get benefit from opioids, and if you and your prescriber decide to try this out you should discuss a trial of treatment carefully.”

Still your point here about treatment of chronic pain is well taken, as are your other remarks about “legacy patients” and the very significant social/cultural dimensions of the “epidemic.”

I have not even finished this article yet. I need to go do my life and will finish it soon. I have to say that as an addicted individual myself for necessity in simply being able to “do life”, I am massively annoyed when I am tossed into the same huge bucket of those who choose to use this, or any drug, incorrectly. It amazes me that I can buy Guns, Gas and Booze all day long. They too kill many each year but there is no restriction in obtaining them. I, on the other hand, have a six year track record of using opioids minimally and only as needed to just get by with diminished pain. I have no motivation to up the quantity and know to stop doing things (and pills) when the pain reaches my tolerance level. If others cannot do that, I am sorry, but I don’t feel like I need to be punished for their indiscretion. I would love to RANT more, but there is no value in that either. I will stop, but I am angry as hell for being put through the wringer each month to simply get my needed help to reduce my pain. My best to all others who are in a similar situation … this needs fixin’!!! Give some of us a “special license” and leave us alone!!!

A person who is addiction-prone is going to become addicted to SOMETHING, no matter what. If there is no availability of one thing in their environment, they will become addicted to something else, whatever is available. On the other hand, an individual who is not addiction-prone to begin with will not become addicted even if exposed to an addictive substance for short-term medical reasons.

Addiction-proneness for whatever reason, is the underlying problem, not the addiction itself. Research needs to look at why one person becomes addicted while another does not.

In looking at statistics, it would be helpful to see a breakdown by race and income. If there are large differences between addiction patterns of Blacks and Whites, or between middle-class and poorer people, that information would be of great use in deciding on a course of action. It is highly unlikely that drug use among inner city Blacks would be similar to that among Whites in a well-off suburb.

It is also important to take into account the growth of a very profitable privatized prison industry with a big investment in preventing solutions that might reduce the number of prisoners. This industry spends millions each year on propaganda to convince the public and lawmakers to keep on using incarceration and to not try other means that might reduce the number of prisoners sent to them. Unless this issue is addressed, there will be no real solution from the American political system, which allows corporations to influence public policy.

While I tend to agree with the author’s points, it is not clear to me that the prescription data includes allowance for the possible increase in how many prescriptions were being written for the same person nor that it allows for a possible increase in the strength or quantity of opioid being prescribed over the years. Either of those changes in prescribing factors could influence the number of opioid related deaths even though relative numbers of prescriptions were decreasing..

While I am in fundamental agreement with the points made here regarding prescribing practices and mortality, as a practicing physician I have a couple comments. First, there is no evidence that narcotics are effective long term for the management of chronic pain, and physicians need to stop using these meds for that purpose. While they do help acute pain, we need to limit the duration of therapy, and more importantly patient expectations, as even high doses of opioids don’t make pain disappear, and a certain amount of pain should be expected and tolerated. (As a person with a history of back surgery and knee surgery I can speak to this). Secondly, most people with chronic pain are endangered more by adding other substances (like alcohol, anxiolytics, sleeping pills, etc)which add to the respiratory depression from the opioid. The recreational drug user is a different situation altogether. Often there death occurs after a stint without opioids, decreasing the person’s tolerance to the drug.

The legacy patients (those started on opioids years ago, not increasing doses, who feel bad when their doses are reduced because of addiction) are not at high risk as long as other meds aren’t started or sleep apnea doesn’t occur, and will require a lot of resource to withdraw, and society probably can’t afford that. We doctors can prevent others from becoming like them in the future, however. Finding a way to deal carefully with the legacy patients economically may require acceptance of who they are at this time and not changing things. Those who use drugs for brain effects are a societal problem. I confess I am a caffeine addict, but as more people use more chemicals for recreational purposes we can expect more mortality because of the creativity of drug designers and the willingness and “need” of the users to push the envelope. Legislation is unlikely to help this, but rather a societal change I don’t see coming as we legalize recreational marijuana.