Evidence means different things to different people. Even quacks and their victims claim to have evidence that their treatments work. Sometimes that evidence consists only of testimonials from satisfied customers or from personal experience. “I tried X and I got better.” “I know Y works because it cured my Aunt Tillie’s arthritis.”

I had a friend who used all kinds of questionable treatments including homeopathy. I asked her how she decided what to try. She said if a friend told her something had worked for him, and if it didn’t seem dangerous, she would try it. That was all the evidence she needed. She didn’t care about scientific evidence because she said, “Science doesn’t know everything.” Comedian Dara Ó Briain had the perfect answer to that: “Science knows it doesn’t know everything; otherwise, it’d stop. But just because science doesn’t know everything doesn’t mean you can fill in the gaps with whatever fairy tale most appeals to you.” When Oprah Winfrey told Jenny McCarthy that experts said there was no scientific evidence that vaccines caused autism, Jenny retorted, “My science is named Evan, and he’s at home. That’s my science.”

There is a huge disconnect between what science-based medicine calls evidence and what alternative medicine and the general public call evidence. They are using the same word, but speaking a different language, making communication next to impossible.

First, there is no such thing as “alternative medicine.” There is only medicine that has been tested and proven to work and medicine that hasn’t. If a treatment currently considered to be alternative were adequately tested and proven to work, it would be incorporated into mainstream medical practice and could no longer be considered “alternative.” It would become just “medicine.” So-called “alternative” medicine can be defined as medicine that isn’t supported by good enough evidence to earn it a place in mainstream medicine.

“Alternative medicine,” along with “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM) and “integrative medicine,” is not a meaningful scientific term, but a marketing term created to lend respectability to things that we used to call by less respectable names like quackery, folk medicine, and fringe medicine. It puts everything outside of science-based medicine under a single umbrella, including things that might work but haven’t been adequately tested, things that have been tested and proven not to work but that are still being used (like applied kinesiology—a bogus muscle testing procedure used by many chiropractors), and fanciful things that couldn’t possibly work, like homeopathy. It fosters the misleading impression that all these things might be equally valid.

There is no such thing as “alternative medicine.” There is only medicine that has been tested and proven to work and medicine that hasn’t.

Science-based medicine has one rigorous standard of evidence, the kind of evidence government agencies require before they allow a pharmaceutical to be sold. CAM has a double standard. They gladly accept a lower standard of evidence for treatments they believe in. However, I suspect they would reject a pharmaceutical if it were approved for marketing on the kind of evidence they accept for CAM.

When science-based medicine evaluates the evidence for alternative medicine, here is what it concludes:

- Acupuncture is just a theatrical placebo.

- Homeopathy not only doesn’t work but couldn’t possibly work.

- Chiropractic is essentially physical therapy contaminated with bogus diagnostic and treatment methods.

- Energy medicine is fantasy medicine dressed up with sciencey-sounding words like “quantum” and “frequencies.”

- Naturopathy claims to stress prevention and to consider the whole patient, but that’s just what every good doctor does. It offers “natural” treatments that have not been tested or that have been proven not to work, like homeopathy. What naturopaths do that is good is not special and what they do that is special is not good.

- Herbal medicine is plausible: after all, half of our prescription drugs came from plants. But every herbal remedy must be tested individually to determine if it is effective and safe; and statistically the great majority of promising remedies fail testing.

So while science says the evidence is lacking, CAM says there is plenty of evidence:

- They cite preclinical studies in animals and test tubes, but scientists recognize that even the most promising preclinical studies can be misleading and must be confirmed in humans.

- They cite case reports, but we know that case reports are only useful as indicators of what science should evaluate with controlled studies.

- Sometimes they can cite clinical studies in humans, but those studies are often flawed. They may be poorly designed or lack a control group, they may be contradicted by other studies, they may be based on such extraordinary claims that we would have to have extraordinary evidence to accept them, and they don’t build on each other to create a coherent body of evidence.

- They cite doctors who say, “In my experience, X is effective.” Mark Crislip, one of my colleagues on the Science-Based Medicine blog, says “in my experience” are the three most dangerous words in medicine, because personal experience is so very compelling and so often leads to false beliefs.

- They rely heavily on testimonials and anecdotal evidence. Scientists know that the plural of anecdote is not data; no matter how many testimonials you accumulate, they can’t ever prove that the treatment works. Think of all the testimonials over the centuries for balancing the humors with bloodletting.

CAM believers find their evidence very convincing, and it is hard to explain why we don’t and how their kind of evidence has been shown over and over to lead people to false conclusions.

Scientists know that the plural of anecdote is not data; no matter how many testimonials you accumulate, they can’t ever prove that the treatment works.

You can’t blame people for accepting that kind of evidence. They are only doing what comes naturally. Science doesn’t come naturally to humans. Evolution equipped us with thinking processes that facilitated survival on the African savannah. Our ancestors had only two sources of information: their own experience and the experiences of other people. If someone said “Don’t eat those berries; they are poisonous,” there was no way to verify the information; but listening to others was likely to help keep you alive. Humans became very adept at pattern recognition. If a pattern of shadows in the bushes looked sort of like a lion, it was safer to assume it was a lion and run away. The cost of over-interpreting patterns was small, while missing the pattern of a real lion could be fatal. Our ancestors learned to make quick decisions: if it was really a lion, they needed to run away now. And emotions served as motivators: fear made them run away faster.

Those thinking processes helped our ancestors survive in a prehistoric environment, but they have become a handicap in the modern world. Today we have more sources of information, but our minds still work the old way. We prefer stories to studies, anecdotes to analyses. We see patterns where none exist. We jump to false conclusions based on insufficient evidence. Emotions trump facts. If your neighbor had a bad experience with a Toyota, you’re likely to remember his story and not buy a Toyota even if Consumer Reports says it’s the most reliable brand. That isn’t logical, but humans are not Vulcans. When we act illogically, we’re just doing what evolution has equipped us to do. It takes a lot of education and discipline to overcome our natural tendencies, and not everyone can do it.

Ray Hyman is a psychologist and one of the founders of modern skepticism. When I asked him why some people become skeptics and others don’t, he said he thinks skeptics are mutants: something has evolved in our brains to facilitate critical thinking. Is it nature or nurture? Or both? Maybe life experiences also incline some of us to think more critically.

So what kind of evidence should persuade us? It’s tricky, because, as John Ioannidis has shown us, many published research findings are wrong. Early pilot studies are overturned by larger, better-designed studies. Studies are influenced by researcher bias. Some are even fraudulent. With over 23,000 scientific journals and 700,000 papers published every year, it’s easy to find a study to support almost any belief.

In this context, there is a hierarchy of evidence:

- Basic science.

- Test tube studies (in vitro).

- Animal studies (in vivo).

- Case reports—of a single patient.

- Case series—reporting on a number of patients.

- Case control studies (example: comparing people with and without lung cancer to see if there are more smokers in the group with lung cancer).

- Cohort studies (example: following people who smoke and who don’t smoke over a period of time to see which group develops more lung cancers).

- Epidemiologic studies (example: studying whether people in countries with more smokers develop more lung cancers. These studies can show correlations, but they can’t determine causation. Countries with more smokers might have other confounding factors that predispose to lung cancer).

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses that evaluate all the published evidence pro and con.

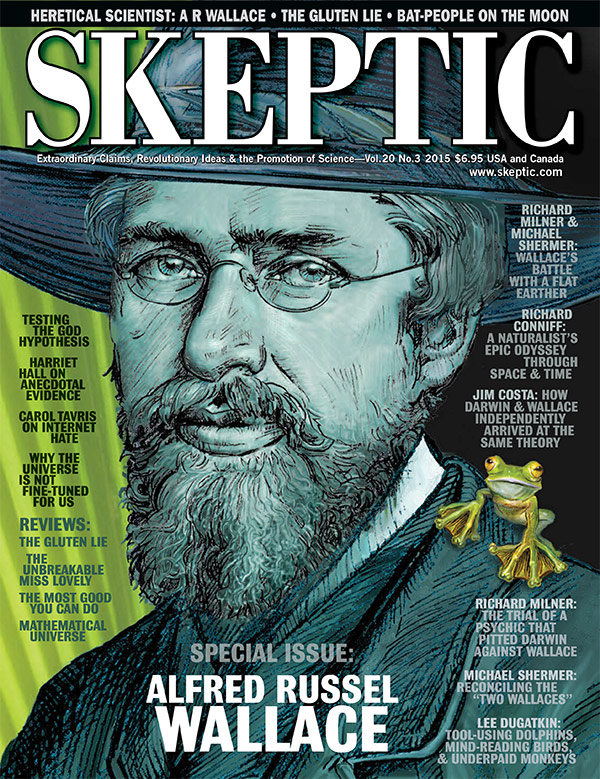

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 20.3 (2015).

The best studies are large, randomized, placebo-controlled, and double- blinded; but that isn’t always necessary or even possible. We don’t need an RCT to know that parachutes save lives. It’s unethical to knowingly endanger a control group by denying them effective treatment. (Anyway, who would volunteer to jump without a parachute?) We didn’t need RCTs to figure out that smoking causes lung cancer because there is an overwhelming body of corroborating evidence from several different kinds of research.

Evidence matters. Science works. It’s a collaborative, self-correcting enterprise. It never relies on a single study. When a finding is true, it will be corroborated by other studies, and a consensus will eventually build based on a cohesive body of evidence. False findings are eventually overturned and discarded. We can trust the scientific method; we can’t trust anecdotes. Sorry, Aunt Tillie! ![]()

About the Author

Dr. Harriet Hall, MD, the SkepDoc, is a retired family physician and Air Force Colonel living in Puyallup, WA. She writes about alternative medicine, pseudoscience, quackery, and critical thinking. She is a contributing editor to both Skeptic and Skeptical Inquirer, an advisor to the Quackwatch website, and an editor of Sciencebasedmedicine.org, where she writes an article every Tuesday. She is author of Women Aren’t Supposed to Fly: The Memoirs of a Female Flight Surgeon. Her website is SkepDoc.info.

This article was published on May 10, 2016.

Amazing intelligent information to consider.

… by the way, Dr. Harriet Hall, your article is brilliant and I love your writing !

When Science Goes Out the Window

Any presentation that is not scientifically tested is at best testimonial.

However, I would challenge anyone who has sought treatment for a herniated disc to say that scientifically verifiable treatment is the best treatment.

When pain issued from the sciatic nerve forces the sufferer into the embryonic position begging some fictitious God for mercy, there is no such consideration of ‘scientific evidence’.

To deny that he or she won’t believe in anything just to assuage pain for seconds is something one would have to experience in order to draw an adequate conclusion.

A sagacious chiropractor won’t perform an adjustment to a herniated disc, since this type of concern is not directly related to a musculo-skeletal issue. However, the chiropractor can certainly apply heat packs or ice packs, depending on what works best for the individual (I found both worked equally as well; a stomp on the foot to shunt pain from one part of the body to the other may also have worked).

Sometimes a chiropractor actually does provide the best possible treatment, albeit not a long-lasting one. A good crack of the neck is great for reducing stress, and I, the participant in a good cracking, can attest to it. However, I don’ believe I’d let a chiropractor attach me to a whirling machine that would spin the bones back into alignment.

Acupuncture? Try it before you dismiss it. My chiropractor, also an acupuncturist, applied the needles when I couldn’t get off the floor, and after an hour’s treatment, I could walk, albeit with baby steps … for about two hours till I was back on the floor again.

Maybe the rest on the acupuncture table made me feel better. Maybe my body relaxed and the pain went away. However, wait till you experience a herniated disc, and boy, you’ll try anything, and gladly pay the fee for a couple hours of respite.

When pain issued from the sciatic nerve forces the sufferer into the embryonic position begging some fictitious God for mercy,”

Oooo, edgy. Maybe all that cutting you do released endorphins that distracted you from the pain. Unfortunately, fields like neuroscience like to posture about the conclusivey conclusiveness about what they know about the brain stem and parts of the spine, and well, it’s pretty obvious they know shit all, to be honest. The same applies to medicine and supplements.

There are tens of thousands of herbs, compounds and chemicals that are untested or only tested in a single application at a few varying doses across a limited number of subjects. The controls on the patient are limited, the controls on the environment are limited by practicality. The ones with the most obviously beneficial effects are integrated into Officially S-M-R-T Medicine(tm) that is Real(tm) Unlike that god fellow – he doesn’t show up to any of the trials), but it takes decade long trials. How long were people doing Tai Chi, which has been shown by at least one study to increase cd(34) count while being glibly dismissed by the powers that be. I buy into mainstream medicine, but to say there is no such thing as an alternative to it is breathtakingly arrogant. It might more sense to call it unproven or what not, but there has to be a category to classify all the tiger penis and dragon fly wing powders that haven’t run the 25 year gauntlet necessary to reach basic demonstrable verification yet.

Conventional medicine is mechanistic, each problem is viewed as an isolated broken part in the biochemical machine. Each part is assigned its own specialist. Each specialist will do their own test procedures and Rx medications. It is not unusual for patients with chronic illness to have many specialists, to have undergone many procedures, and be taking multitudes of pharmaceuticals. I have seen many patients taking over 10 medications, some as many as 20. How much research is done on the interactional affects of taking these medications and procedures (many surgeries for example)? Zero. How scientific is that?

This article illustrates the difference between belief and understanding. Belief is the acceptance of something as “true” based on the dictates of authority and in some cases wishful thinking while understanding is the acceptance of something as “true” because you understand WHY it is true.

I have used this example before. I was once asked if I believed that two plus two makes four?

My answer was “NO” but because I understand the rules and procedures of mathematics I understand why and under what circumstances two plus two makes four.

Belief is a word I use rarely and with great care. I would far rather understand something than simply believe it. Understanding is much more difficult but it is worth the effort.

I like skeptic.com and read many of the articles, but I’m often struck by their condescending tone; Dr Hall is an extreme example of this. It’s lots of fun to preach to the converted and there’s plenty of self-satisfaction in pooh-pooh-ing the “woo-woo” crowd, but I think a more conciliatory approach might work better.

I totally agree that evidence based science is the best way to go, but Dr Hall ignores the reasons that many people turn to alternative medicine. With public funding for research drying up universities are increasingly getting private funding, which usually has strings attached. It’s been almost impossible to get funding for medical marijuana research, for example.

Couple this with the expense of FDA testing of new treatments and it’s only patentable, profitable treatments that get funding or testing.

The scientific method is a tool. Like any other tool it can be used for good or bad. Dr Hall would better serve her readers if she applied her scepticism to our “medical-industrial” system. I think Dr Andrew Weil’s comment sums it up very well: we don’t have a healthcare system in the US: we have a Disease Management system.

And a really bad one. Among the currently “known” risk factors for cardiovascular disease, cholesterol is the favored one. The pharmaceutical industry has developed cholesterol-lowering drugs, with barely any impact on morbidity. An alternative hypothesis is homocysteine, which is related to non-optimal methylation. Many studies showed that this theory is a much better one (some published in the 50s & 60s): lowering homocysteine (improving methylation) levels reduces morbidity and some of the reasons why it works are well understood. A skeptic might wonder why 60 years later it is still not the favored hypothesis. Maybe just a coincidence, but these studies used supplements like vitamin B6, B12, C, … and therefore cannot be made into patented drugs. Anyone with cardiovascular disease should read more about methylation and homocysteine.

Some of the skeptics on this thread should remember that the scientific method requires a theory that is in accordance with the observations: you need data and theory to match. Many evidences in evidence-based medicine are just identifying risk factors, without a clear theory of why those risk factors are actual causes. It is a difficult problem to solve in many cases, and (most) scientists are trying to do their best. But we need to remember this, because it helps understand why some evidences are stronger than others.

The only way to truth is rational thinking – or, in science, the scientific method. Having said that, and I certainly support much of what is said in this article, scientific investigation has also shown us that the human being is a very complex organism with sufficient individual differences so that different individuals may or may not respond to the same medication. That, of course, doesn’t mean that anything goes – only that these nuances in human physiology need to be understood better. I, for example, respond to Echinacea when I’m coming down with a cold. Not all people do, but I’m not going to stop taking it because some scientific study says it doesn’t work. Doesn’t work how – to what extent – in what individuals.

Have any of you read any of the very scientifically based research on some of the complementary and alternative techniques? Oh yes it is out there. Are any of you aware of the poor science that has led to unsafe medications being approved by the FDA?

I totally agree.

I hear many of the skeptics talk about the evidence-based method. I just wonder how many have actually read the corresponding research, and how many have the skills to understand it. I think many people keep mentioning evidences they are not able to verify themselves. Most of the posts in this thread have not questioned the evidence-based or scientific method, but the quality of the evidence, and all the factors that can bias it (money, conflict of interests, irreproducibility, correlation vs causation…).

Very good questions for this article, “skeptical of medical research”. Thanks.

And “USMacScientist”, I completely agree with your comments immediately above as well as elsewhere on this thread.

Dr. Harriet Hall, yet another self-congratulating skeptic thinking deep inside the box. What a startling narrow world-view and sad lack of imagination many of the skeptics exhibit.

Yeah, doesn’t it suck when doctors use EVIDENCE.

No, BillG, it doesn’t suck at all. What in my comment would lead you to such an irrational conclusion?

What sucks is when smug, “big-brained”, so-called skeptics use emotion and a lack of critical thinking to disparage others for a lack of critical thinking. One sees that on these pages all too often.

Plenty of commenters above have pointed out the many flaws in the SkepDoc’s article. There are others besides, but a good starting point is to read those comments if your critical thinking skills are not adequate to the task of finding them on your own.

It’s called sarcasm. Anyhow, I will repeat the key word and the basis of the article: EVIDENCE.

A good scientist, skeptic or critical thinker (thought), will be open minded to the evidence – with the proper standard when approaching it. The contrarian views from SkepDoc’s article seems to be what qualifies as evidence.

Don’t believe me, her or anyone: look at the EVIDENCE and the degree of a risk/benefit of what your willing to accept or reject.

Difficult to respond to sarcasm without returning sarcasm (which leads where?) or dealing with it as though a point were being made.

I don’t take exception to EVIDENCE. The key phrase you used was “open minded”. The SkepDoc, like Shermer, like many others of the smug, “big-brained”, so-called skeptics on this site, evidence astoundingly closed minds (IMO) regarding a variety of phenomenon, yet never hesitate to pass judgement. Often, they simply dismiss evidence as improper, unimportant, insufficient. Open minded, they ain’t.

Cryonics does not claim to work. It claims that in the future it might.

Is that science?

I think that is selling hope. Selling means money.

http://theconversation.com/could-thalidomide-happen-again-46813

Thalidomide hangs over us still.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electroconvulsive_therapy

Electroconvulsive ….therapy…?? Now considered high risk.

Mainstream and alternative are filled with hope…and pitfalls…and successes….and terrible failures.

If ‘it’ works for me, then ‘it’ works for me. ‘It’ worked for someone else it was claimed which is why I wondered if ‘it’ would work for me and so I tried ‘it’ and ‘it’ did work for me.

For you ‘it’ probably wouldn’t in all honesty work.

Then again.

Sometimes a professional will prescribe a certain medicine with the warning that if it has side effects which you don’t want stop using it. Meaning that this medicine works for some Aunties but maybe not you.

As with Thalidomide the warning came too late for many.

Agree with the initial statements about evidence-based medicine, but not with the statements about integrative medicine. Just because there are no studies you can’t say some treatments are not useful. Actually, the most respected medical institution in the the world, has an integrative medicine department, which uses the scientific method to go and test some of the claims of alternative medicine, and the ones they find useful, they add to their treatments as complements to the mainstream approaches.

Being a skeptic shouldn’t make you blind to the benefits of other approaches only because there is no evidence YET of their benefits.

See: http://www.mayoclinic.org/departments-centers/general-internal-medicine/minnesota/overview/specialty-groups/complementary-integrative-medicine

Mayo Clinic physicians conduct dozens of clinical studies every year to learn which treatments work, and they share that information with their patients and colleagues.

Of course, you can’t say untested methods are not useful. You also can’t say they are useful. You can’t say anything at all. So, why use them? Try to get them tested. If they work, they’re not alternative medicine. They’re just medicine. Exactly Dr. Hall’s point. Why not find out? What’s to lose?

Ken,

That’s exactly what I said is being done at the Mayo Clinic: Rigorously testing as many of those claims as possible using the scientific method, finding which ones hold under scrutiny, and then recommending those as complementary treatments for known illnesses and ailments.

Interestingly enough, those studies have found that several of those treatments qualified by some as “quackery” actually work much better than a placebo, and in some cases, even better than the accepted mainstream medical treatments.

As I said:

“Actually, the most respected medical institution in the the world, has an integrative medicine department, which uses the scientific method to go and test some of the claims of alternative medicine, and the ones they find useful, they add to their treatments as complements to the mainstream approaches.”

“Mayo Clinic physicians conduct dozens of clinical studies every year to learn which treatments work, and they share that information with their patients and colleagues.”

I am very confident that the scientific method and well designed, controlled studies do uncover the truth in the end. Nevertheless, I undertook a series of acupuncture treatments for my very painful Lateral Epicondylitis because 1) the orthopedist said she had nothing to offer me other than an 18 month recovery period and 2) my health insurance covered it. After four visits in as many weeks, I could sleep through the night again. You may think this is the result of the placebo effect. In fact, I may as well. But I don’t care, the result was what I was looking for.

I have a suspicion that one of the driving factors that keeps alternative medicine thriving is the dismissive attitude of many Doctors and Nurses toward certain ailments – and patients. It seems anything that could possibly be psychosomatic is cavalierly written off by Doctors as “Just one of those things” and patients are often left wondering if the Doctor missed something in that nanosecond of consideration they gave their concern. In this era of ‘cost contained’ medicine you’re lucky to get a nanosecond.

How many of us have gone to a Doctor for a particular problem and had the Doctor get distracted by something else and have them ignore what brought us into the office in the first place? I’m not saying Doctors shouldn’t act on issues they see (with their training they will see things many patients won’t) … but to ignore, or blow off, the reason the patient came in… well, that’s kind of insulting to the patient.

The crazy, alternative medicine peddlers may be earning their keep just by letting the patient know that they are being heard. There may be nothing that can be done about the problem except learn to live with it … but living with a chronic ailment can be made easier if one feels like one has been heard. Being heard is better than being treated like a bag of biological systems & process that has the (unfortunate) ability to speak.

Also, if some woo-woo treatment provides relief via the Placebo effect, then the treatment works and most patients aren’t picky about the specific mechanism.

I told this story before that a Skeptic friend was talking with a non-skeptic friend of his, and found out that the non-skeptic was getting some treatment for a chronic problem that was apparently only working via the placebo effect. The skeptic friend was tempted to explain this to his non-skeptic friend but it occurred to him that the placebo effect doesn’t work very well once you know it is the placebo effect. Education his non-skeptic friend may be robbing him of some much needed relief.

One of the reasons many people believe the quacks is because they cannot access reports for properly designed trials. Most scientific papers are hidden behind paywalls or locked away in research libraries. If real scientists want the public to believe them more they need to make sure the average joe can actually go and see the study see the data see the method and slowly begin to understand there is a difference between real science and all the crackpots.

That is up to the publishers… I do not know any scientists who approve of the HUGE subscription prices for these journals. Those prices create a huge obstacle for scientists in poorer nations.

Strongly agree, but even some developed country universities find it hard to pay for some journals. Asking for upwards of $30 to download a paper is beyond the reach of many developing country scientists, and a barrier to research in developing countries.

Anecdotal Evidence follows.

I had bumps on my head. You could describe them as pimples, but they weren’t quite pimples. You could describe them as boils, but they weren’t quite boils. For two years they would pop up, hurt for awhile and then disappear. They were just annoying enough to be a little distracting, but not so annoying that I felt a need to see a doctor. Finally I got an appointment. The next day, (the appointment being 6 weeks out), I talked to my mother. She too had bumps that sounded just like this. My father had the same bumps. He had gone to see a dermatologist and had taken drugs for 12 weeks to fight it without any luck.

Mom started using 1 tablespoon of bakings soda mixed with 1 cup of water as a shampoo followed with 1 tablespoon of apple cider vinegar mixed with 1 cup of water as a rinse. I decided to try it. Within a week the bumps were gone. I still went to the dermatologist. He was unable to find any bumps on my head (because they were gone). He did biopsy a mole.

The bumps have returned twice in the subsequent 5 years. Each time I have used baking soda and apple cider vinegar for a week and had them go away. I might use this formula all the time to wash my hair, but Head and Shoulders is much more convenient.

Arm and Hammer didn’t make any money from this. A baking soda based shampoo might work… Arm and Hammer does have baking soda based anti-perspirant. Maybe I need to check to see if they have shampoo now.

Anyone telling me it doesn’t work has to face a believer. The annoying bumps aren’t there anymore.

“It worked for my Aunt Tillie” isn’t enough. “It worked for me and solved my problem and I am not getting a dime from telling you” helps me.

to repeat my self again and again …

If you hope that something will help a condition you have . TRY IT with regard to possible dangers.

Any attempt to discuss a scientific worldview with a believer gets you labelled as “close (sic) minded” or in standard English,,

” closed minded”

My technique is to say ” HMMM,,, Tell me more about THAT!!”

Evidence?

Evidence ???

We don’t got to show you

no steenkin’ evidence !!!!

Dr. Latero Sidethink Hp. D

Not only is there a difference between the popular and the scientific understandings of the word “evidence”; there is also a difference in the understanding of the verb “work” (as in “This treatment works”).

One of the commonest ways in which people armor themselves against scientific evidence of the inefficacy of their favored “alternative” treatments is to say, “Well, it works for me.” What they typically have in mind is some number of instances in which they used the treatment X and thereafter they felt better.

That is, people tend to count mere instances of succession as instances of the treatment “working.” So if you present them with scientific evidence that X is ineffective, they will say, “Well, maybe it didn’t work for those people, but it works for me.”

It’s not even a confusion of correlation with causation. Correlation is a genuine statistical regularity. When people say, “It works for me,” they usually don’t even have that. They have just a recollection of some positive instances of the use of X followed by their feeling better. These instances may be selected from instances of their use of X, in some of which they did *not* feel better, instances in which they were already on their way to recovery when they used X, and so on.

Evidence based medicine did not get started until about 1990, and many mainstream physicians still do not practice it. Just look at the over-screening for cervical cancer in the U.S., for example.

Well that’s strange…I seem to remember a Dr. That discovered milkmaids did not get smallpox and then created a vaccine based on his studies. Hmmmm. Let’s see, that was in… Oh, and the discovery of penicillin. That was in….and polio vaccine….plus, Dr.s have known the high correlation with smoking and lung/ mouth/throat cancers for over 200 years. Just to name a few.

When I was in grade school, in the 60s, I remember all those telethons Jerry Lewis did to raise money for. .oh yeah, RESEARCH for medicines for muscular dystrophy.

Excellent points, Peggy. Careful, though, you come very close to upsetting the sarcasm police.

You might want to take look at the Wikipedia article on “evidence-based medicine” at

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evidence-based_medicine

Also see

http://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/2013/01/mhst1-1301.html

whence this quote:

“When the first article on evidence-based medicine was published in November 1992, the methods were not new; they were nearly a quarter-century old. Like its earlier iteration in 1978, the 1992 version of evidence-based medicine was developed and presented in the immediate context of medical education at McMaster. This intimate relation between medical education and medical methodological reforms should be no surprise; as exemplified by Abraham Flexner’s report and the changes it conveyed to the North American medical world, reforms in medical education and medical practice in North America have been closely related.

“But why did these methods become so widely accepted in the 1990s? There appear to be several reasons to explain the meteoric rise of evidence-based medicine. First, the name itself was indeed a good choice; it was catchy, and it conveyed an intuitive message about the nature of the method. Most physicians did not need to read an entire article series to understand more or less what the name denoted. Second, the support of the McMaster department and JAMA’s Drummond Rennie were critical for advancing the methods and their introduction to medical discourse. Finally, the social and cultural milieu of North American medicine in the early 1990s, into which EBM made its debut, was on the whole ripe for the new methods. Quantification practices, the use of statistics and epidemiology, the introduction of computers and online digital databases, and new clinical research methodology saturated the medical environment of the time.”

Another example: the “standard of care” for women with high risk pregnancies is to place them on bed rest. There is, however, no evidence that bed rest is effective; to the contrary, evidence indicates that bed rest can actually be harmful to the women.

Most interesting that so many of these comments are verifying the exact points that Dr. Hall has made. It seems as though the “Aunt Tillies” of the Internet have come here to leave their comments. Anecdote over scientific study, conspiracy over fact.

Anyone so interested can gain excellent scientific insight into the assorted CAM nonsense by viewing Dr. Hall’s excellent series of Youtube videos.

Science evolves and the current standard of care will probably be seen as quack medicine in a few decades… You might want to be a bit more cautious and skeptic about your confidence…

You mean science continues to investigate and sometimes discovers better ways?

Stupid science. Why can’t it just decide absolutes right now like the woo promoters do?

“The defense mechanisms of The Imposter are: sarcasm, name-dropping, self-righteousness, the need to impress others and the need for others’ approval.”

― Manning Brennan

Sorry for the sarcasm but is your point that because we might one day see something as quackery that is not currently thus considered that we should be more open to current quack theories and not be so demanding of evidence?

I guess that would be true if the logic was inverted and quack theories often became standard practice. I’m open to examples.

Very nice summary article and hard to find anything here to complain about.

Dr. Hall fails to mention that worldwide pharmaceutical sales are in excess of one trillion per year. In 2014 it was 1,057 Billion. The income of the medial services industry in the US was 1.5 Trillion in 2012. That kind of money talks its own language and buys influence. It buys Doctors and Politicians who sell out for the money they make.

There are cancer cures available besides chemo, radiation and surgery which are not actual cures. But that’s all you can get from the main stream doctors. Watch the 20 hours of video documentation in The Truth About Cancer series.

https://thetruthaboutcancer.com/

https://www.cancertutor.com/cancer-documentary/

They have thousands of testimonials from people who have been cured of cancer in other countries outside of the US who don’t have the medical mafia we have in the US.

Why does the Cancer Industry try so hard to shut down The Truth About Cancer series. Answer: They are protecting a Trillion dollar industry. Money talks.

Or you can watch the documentary “The marketing of madness” that explains how “placebo washout” is shamelessly used to improve clinical trials of psychoactive drugs. I am a scientist, and I love Science. It is just disheartening to see how it is perverted by some for financial profit.

Many patients, especially with chronic illness, experience a long trial & error process that in many cases yields no positive result (just check out the website crowdmed.com to see how many of those are desperate). I guess their view of ‘evidence-based’ medicine is probably not so great, making them easy prey for less scientific approaches. The problem is the “good” doctor mentioned in the article is rare: most doctors have been trained in a very specialized framework, and are not able to see the whole picture (or just don’t have enough time to do so in a 5-to-10-minute consult). The industrialization of medicine has dramatically lowered the quality of care.

Finally, I think one can understand that when you are sick you only care about getting cured. If after taking an unproven “treatment”, you get cured, even by placebo effect, you probably won’t care much about the reason.

Unfortunately, the links you posted are classic quack central locations featuring characters like Burzynski and the seeming ever present nonsense about pH being “too acid” then promote nonsensical fixes.

And, really, cancer is caused by “nasty microbes”?

Wow.

OMG, even Hulda Clark’s “protocol” is promoted as viable! This is where she shows you how to build a device to zap the cancer-causing parasites throughout your body. Actually, these parasites cause ALL disease according to her.

Ironically, she actually died of cancer.

lost me on the home page with “Cancer Fighting Recipe: Broccoli Sprouts Dip with Hemp…”

I suspect you have not learned anything from the article. oh, well

Thousands of testimonials? What about published papers on oncology from developing countries or countries without the “medical mafia”. I agree with the author’s point that many testimonials do not equal data.

Though traditional medicine tries to be sceintific, the science it uses is mainly incomplete, and the practice of using it is fraught with unconscious biases driven by scientism and financial incentives. The revered statistical scientific method using p values of less than 0.05 is very controversial, as Tom Sigfried has nicely summarized, and big pharma has done a masterful job of buying off the medical establishment to purvey its wares.

Building bridges is science based practice. Treating patients is statistical risk management. Science is great for it, and the best of it should be used, but there is a scarcity of strong science in medicine, and so “alternatives” can be impossible to avoid.

Simple exemplar question; are statins the best way to prevent. Cardiovascular disease from developing in people who don’t have it? Science has not answered that question, yet doctors prescribe them as if they were proven safe, effective and without risk. And as if they’ve ever been effectively compared to a strong regimen of lifestyle change with exercise, stress management and diet.

Docskeptic needs to be more skeptical.

Although Dr Hall is largely speaking to the converted, I was struck by Roy Hyams’ thought that I might be a mutant, possessed of some kind of neural mutation! I think that I have a simpler explanation. Only in the US is it necessary, in the modern, developed world, to have a ‘skeptical society’, whose sole function is to debunk. Although Europe has its share of crackpots, charlatans and blatant con-men, there appears to be much more of a critical approach; we seem to be less easily panicked by the latest scare or fad like MSG in the sixties, MMR or gluten in the more recent past and I wonder what it is about modern, American society that makes it so vulnerable? Too much religion? Too much affluence? Too many wide open spaces? Too much political power on the world stage? Thinking that Donald Trump might make a viable President? I am afraid that I don’t have any answers but some enterprising sociologist might.

I agree with what you say about the US mostly. I lived most of my life in the UK. I don’t think it is much better there. It might appear to be but, in my view, that is something of an illusion. It is a far more buttoned down society in terms of what people feel they can say or do publcly. More conformist you might say with, indeed a lot more institutional, policial and informal control over what people can say.

I am against this environment and against control of speech. In some contexts though it can serve to blunt somewhat the vocal advocacy of pseudo science. It is telling how Andrew Wakefield for example, has made a new life in America, not the UK or EU.

Again I don’t present any of this as confirmed or fully researched. I might be wrong and indeed other factors might account for all this. One being, of course, that UK people are more scientific. I don’t really believe that for one minute.

Great questions. We are an ethnocentric society that forgets there is life outside of the United States where many of our problems have already been solved. When will we learn?

too many women’s magazines LOL

I see some problems with the presented approach.

1. Financial aspects: large, randomized, placebo-controlled, and double-blinded studies are expensive.

Who will finance a study that a common herb might be be helpful in some particular condition? Who will finance a study if the ailment concerns only a few hundred people on the whole planet – or only some poor people in a poor country where nobody can afford expensive medicine?

2. Publication Bias: If five studies investigate the effectiveness of some particular active agent, three have inconclusive results, one rejects and one supports positive effects: which studies will be published, and how prominently?

3. Statistical aspects: a proof in this context is usually some sort of statistical analysis. Apart from general problems in the area (and good physicians are not necessarily good statisticians), what does this tell? It tells that the medicine did help some (and more) people and didn’t help (fewer) others. How am I to know into which category I might fall? I have a history of polio, a broken back and Lyme borreliosis, would this affect the category I am in? Are there any others in the clinical sample with a similar history?

4. In this situation, it seems wise to apply some well-tested, but not necessarily proven ideas from complementary medicine (like I didn’t need a study for the parachute): a moderate amount of physical exercise, a healthy diet (this is already shaky ground: not clear what to avoid: fat? sugar? cholesterol? artificial additives?), a healthy environment (often not easily available). Some additional items to include are suggested: pomegranate juice, green tea, mushrooms, legumes… I don’t know if anything of this is scientifically tested and if anybody would finance such studies.

So, what’s your point?

What do you mean, “what’s your point”?? He points out some significant issues with “conventional medicine” that skepdoc ignores. I think he makes some very valid points.

“What’s your point?” may not have been the best way to put it, but I agree that Fischer’s points are somewhat “beside the point.”

In his first three items he points out problems with the science approach, but they’re not really problems with Dr. Hall’s presentation — they’re simply complexities that our evidence-based practitioners need to deal with. Yes, good research costs money. So? Does that mean we should abandon efforts to do good research.

But the fourth point is confusing: “apply some well-tested, but not necessarily proven ideas from complementary medicine”: since when are moderate exercise and healthy diet considered “complementary” or “unproven”?

Of course it’s not always easy to determine healthy diet…but that doesn’t make it “complementary.”