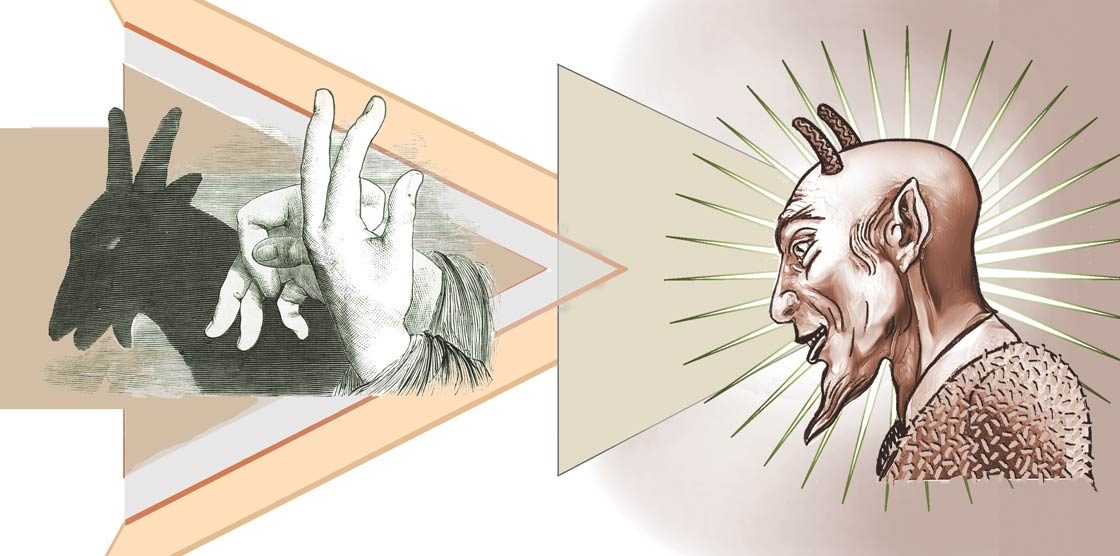

When a mysterious epidemic of hallucinations was reported to have broken out in Oregon in October of 2016, media outlets around the world portrayed the story as a baffling medical mystery. There’s only one problem: it never happened. The case of the hallucinating Oregonians serves as a stark reminder of the threat posed by an uncritical media, and the need for skepticism and critical thinking.

“Things are seldom what they seem, skim milk masquerades as cream.”

During the early morning hours of Wednesday October 12th, 2016, an extraordinary story began unfolding in the community of North Bend, a small picturesque suburb of Coos Bay nestled along the Pacific Ocean in southwest Oregon. At about 3 am, police responded to a 9-1-1 call of vandalism. The complainant was a 57-year-old woman who was a live-in caregiver for an elderly resident. The caller claimed that several people were trying to remove the roof of her car. When police arrived, they could find no evidence of any crime and soon left. Two and a half hours later, the same woman again called to report that the vandals were back and trying to remove her car roof. Once again police rushed to the scene but could find nothing out of the ordinary. In fact, the responding deputies, Doug Miller and David Blalack, could find no evidence that any crime had been committed. Given the unusual nature of her claims, police grew suspicious that the woman may have hallucinated the episodes. She was taken to the nearby Coos Bay Area Hospital where she was examined by medical personnel, “appeared fine, and returned home.”1

Numerous media outlets reported that over the next several hours, the two responding police officers, a 78-year-old woman whom the complainant was caring for, and a hospital worker, all began to hallucinate. Those affected were reportedly hospitalized and the emergency room was quarantined. At first, investigators suspected the culprit was a transdermal Fentanyl patch that the elderly patient had been using to control pain. Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opiate. It was suggested that all of those affected may have inadvertently touched the patch. Hence, one newspaper headline proclaimed: “Doctors Left Stumped as Bizarre Hallucination-causing Illness Seemingly Spread by Touch.”2 A HAZMAT team searched the house. They reported that all of the patches were accounted for, and the theory was discarded. Dr. Zane Horowitz of the Oregon Poison Center noted that it was impossible for the patches to have been responsible for the symptoms unless they were stuck to the skin of those affected and left there.3

It’s a fascinating story filled with mystery and intrigue. The headline in Popular Science asked: “What Caused This Baffling Outbreak of Hallucinations?” In the article, reporter Samantha Cole summed up the enigma: “Five people fell ill and started hallucinating, one after another, following contact with one woman who started seeing things in the dead of night…as the day wore on, everyone who’d come in contact with her started showing similar symptoms.”4 YourNewsWire.com, whose header boasts in large print “News, Truth, Unfiltered,” led with the headline: “Doctors Confirm Bizarre Spread of ‘Person- to-Person’ Hallucinations,” yet not a single physician was quoted or cited in the article.5 As the days went on, the accounts grew more elaborate. By October 28, Journal Online, a major digital newspaper based in the Philippines, reported that after the second callout, “An elderly woman in the care of the seemingly-crazed caregiver then began speaking nonsense and acting erratically,” and went on to note that those affected were hospitalized and quarantined indefinitely.6 Their source, a report from OregonLive, made no mention of the woman “speaking nonsense and acting erratically.”7

The Nature of News

In reading numerous media reports of the affair, several aspects stood out as odd. First, the same source kept appearing again and again: an account filed by KVAL-TV in Eugene, Oregon, which broke the story. The KVAL report stated that “Five people fell ill from an unknown hazardous material that appears to be spreading by contact and causing hallucinations.”8 What stands out in reading this account is that it is a breaking news story, and breaking news is notorious for containing errors and omissions.

“Doctors Left Stumped as Bizarre Hallucination-causing Illness Seemingly Spread by Touch.”

On Tuesday October 18, KVAL-TV offered a brief follow-up story titled: “People Afflicted by Mysterious Hallucinations in Coos Bay Sent Home from ER the Same Day.” Hospital spokeswoman Barbara Bauder said that every one of the five people involved had been checked out in the Emergency Room and were released by noon of the very same day. She emphasized that they had neither been quarantined nor hospitalized.9 My journalistic instincts were now telling me that something was seriously amiss. Imagine, no fewer than five people including two police officers (who are allowed to carry guns), are supposedly brought to the hospital ER suffering from hallucinations. Yet all five were examined and sent home within hours! What’s more, they were never admitted or kept for observation. Even more suspicious is the absence of descriptions of the supposed hallucinations (aside from the perceived roof-raising incident).

The Hallucination Outbreak that Never Happened

I contacted the head of the agency officially responsible for investigating the incident: Coos Bay County Sheriff Craig Zanni. Sheriff Zanni explained that only one person was suspected of having hallucinations: the woman who reported her car being vandalized. Everyone else soon felt unwell with lightheadedness, nausea and mild euphoria. They were checked out at the hospital and released, as their symptoms quickly resolved. The hospital worker who felt unwell also had flu-like symptoms, and the hospital reported that she had recently been exposed to the flu! Zanni expressed his disappointment with the inaccurate, sensational reports that all of those involved had been suffering from hallucinations.

Two weeks after the incident, I used an academic database to search over 1,300 newspapers, news blogs and websites using the words ”Coos Bay” and “hallucinations.” Just one site had updated the story and reported it accurately: local journalist Lynne Terry of OregonLive. However, there is one major caveat. On October 12, she had reported, like other outlets, on a “mysterious illness that can cause hallucinations.”10 The following day, in updating the story, she described it as a “mystery illness” but made no mention of her erroneous report about contagious hallucinations. At the very least, she should have noted that her previous report was incorrect.

The Diagnosis: Mass Suggestion Complicated by Lazy Journalism

Episodes of mass suggestion similar to this case are common in the medical literature. While they are not everyday events, they occur with enough frequency as to be well-known to researchers in the field of psychosomatic medicine. But how could the symptoms have spread among those involved? The original KVAL story stated that the symptoms first spread from one of the officers, then the other, followed by the 78-year-old woman, and lastly, the hospital worker. Given this sequence, it is significant that during the early stages of their investigation, HAZMAT investigators became aware that the 78-year-old woman who was being cared for was using opioid patches to control pain. It was initially suspected that these patches may have been responsible for the caregiver having “hallucinated” the vandalism of her car. HAZMAT authorities made a point to say that they believed the illness was being spread by touch.

YourNewsWire.com, whose header boasts in large print “News, Truth, Unfiltered,” led with the headline: “Doctors Confirm Bizarre Spread of ‘Person- to-Person’ Hallucinations,” yet not a single physician was quoted or cited in the article.5

So, soon after the woman was evaluated for her hallucinations, one by one, the other four began to feel unwell. While all of the patches were later accounted for, and the Fentanyl scenario was eventually ruled out, it was being actively considered while the house was being examined and could have easily spread the belief that the opioid patches were triggering the symptoms. Mass suggestion is spread by a belief. Lightheadedness and nausea are common symptoms in outbreaks of mass psychogenic illness, but euphoria is not, but it makes sense here because during outbreaks of mass suggestion, symptoms typically reflect the outbreak scenario. For instance, psychogenic symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhea and nausea are common after rumors of food poisoning, while suspected chemical exposure often triggers dizziness, headache and itchy eyes. It cannot be over-emphasized that mass suggestion is not a disorder but a stress reaction in response to a belief. It occurs in normal, healthy people, and it can happen to anyone. Symptoms usually resolve quickly, and did so in this case.

Mass suggestion is spread by a belief. … It cannot be over-emphasized that mass suggestion is not a disorder but a stress reaction in response to a belief. It occurs in normal, healthy people, and it can happen to anyone.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 22.1 (2017)

Buy this issue

What does this episode tell us about the state of journalism in the 21st century? Most sites simply carried the initial breaking news story, never bothering to verify it or contact authorities for clarification. In fact, when the Coos County Sheriff suspended his investigation into the episode on October 27th, local media outlet KCBY-TV continued to maintain that the Department had closed its inquiry into the “five people [who] showed symptoms of hallucinations.”11 This is a story of two outbreaks, the first involving mass suggestion, while the other was even more concerning: an outbreak of shoddy journalism. ![]()

References

- KCBY Staff. 2016. “Coos Sheriff Suspends Investigation into Recent Hazmat Situation in North Bend.” KCBY-TV, Coos Bay, Oregon, October 27. Accessed online at: http://bit.ly/2e3JUl2

- Warnes, Indra. 2016. “Doctors Left Stumped as Bizarre Hallucination- causing Illness Seemingly Spread by Touch.” The Express, October 22.

- Terry, Lynne. 2016. “Mystery Illness Probably Not Caused by Fentanyal,” October 12, accessed at: http://bit.ly/2fDjIhz

- Cole, Samantha 2016. “What Caused this Baffling Epidemic of Hallucinations? Just in Time For Halloween, a Tale of Pathogens and Madness.” Popular Science, 18 October, 2016.

- Adl-Tabatabai, Sean. 2016. “Doctors Confirm Bizarre Spread of ‘Person-to-Person’ Hallucinations.” Accessed online at: http://bit.ly/2gfhadf

- “Oregon Hospital Quarantined after Unexplained Mass Hallucination.” Journal Online (Manila, the Philippines), October 28, 2016.

- Terry, Lynne. 2016. “Mysterious Illness that can Cause Hallucinations Hits Coos Bay.” October 12, accessed online at: http://bit.ly/2dTrLIq

- “Unknown Illness Appeared to Spread from Woman to Deputies.” KVAL-TV (Eugene, OR), October 13, 2016, accessed online at: http://bit.ly/2eu6hDN

- “People Afflicted by Mysterious Hallucinations in Coos Bay Sent Home from ER the Same Day.” KVAL-TV, October 18, 2016, accessed online at: http://bit.ly/2fp4sao

- Terry, 2016, op cit.

- KCBY Staff, 2016, op cit.

About the Author

Dr. Robert Bartholomew is a medical sociologist who holds a Ph.D. from James Cook University in Australia. He is an authority on culture-specific mental disorders, outbreaks of mass psychogenic illness, moral panics and the history of tabloid journalism. He has conducted anthropological fieldwork among the Malays in Malaysia and Aborigines in Central Australia. His most recently books are A Colorful History of Popular Delusions with Peter Hassall and American Hauntings: The True Stories Behind Hollywood’s Scariest Movies—From Exorcist to The Conjuring with Joe Nickell.

This article was published on June 28, 2017.

In the mid 1980’s there was a similar outbreak of mass hysteria in children’s day care centers with allegations of wide spread sexual abuse. Law enforcement bought into shoddy science and people went to prison. Dorthy Rabinowitz writing for the Wall Street Journal was nominated for a Pulitzer, exposing much of how and why it happened.

Carbon monoxide

Excellent article examining the connection between perception and effects. My own experience? Eating a can of tuna fish and finding white crystals inside the can, followed by my feeling sick and light headed. Later I found out these harmless objects occur often in canned fish…I still pay attention to my body but now it’s with a calmer response to my “reactions.”

Yesterday, the NYTimes published an article about competing studies of the effect of the minimum wage increase in Seattle. To their credit, at the beginning they stated “neither study has been peer reviewed.” Usually this type of caveat appears at the end of some supposedly science article. But doesn’t it seem strange to give publicity to alleged empirical studies that may not have any credibility?

My theory is that the hallucination contagion was REAL, and quickly spread to many journalists! Seriously though, Googling key words brings up over 17000 hits; adding the word ‘hoax’ to the words limits it to about 8000. Virtually ALL of those 8000 are included because they also have a story about climate change being a hoax. The point is, nine months later, virtually NONE of the stories is retracted!

But shoddy journalism has always been with us. I’ve seen newspapers from a century ago who thought a rival in town was just ‘getting their news from our pages’. They would then post a completely fabricated story, which would be copied by said rival, and then expose what had happened.

The subconscious mind takes everything very literally and appears not to have a sense of humor. It was probably meant to provide us with warnings of danger, but it also provides us with dreams, which may not be considered as literally true. Hallucinations may be called waking dreams.

The idea of spreading a story through human retelling can cause the story to grow far beyond the original in both size and scope, but as far as the caregiver was concerned, it may have been that looking after an elderly person had taken a toll and that sleep deprivation may have been partly responsible.

The question that we must ask ourselves when reading or hearing about an unusual story would be, how does this affect me?

Orson Welles 1938 was much imaginative.

Thank you for researching this (non) event and providing such a succinct and well-documented discussion of it. I will book mark this article and refer people to it if/when I encounter folks who believe that it happened. I am grateful that skeptic’s groups are addressing new falsehoods as they appear.

Lily Tomlin once said “No matter how cynical you become it’s never enough to keep up.” Something similar may be said about examining things rationally (AKA skepticism).