What is a conspiracy, and how does it differ from a conspiracy theory? Michael Shermer explains who believes conspiracy theories and why they believe them in the following essay, derived from Lecture 1 of his 12-lecture Audible Original course titled “Conspiracies and Conspiracy Theories: What We Should Believe and Why.”

On Friday, March 15, 2019 a 28-year old Australian man wielding five firearms stormed two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, and opened fire, killing 50 people and wounding dozens more. It was the worst mass public shooting in the history of that country, prompting Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern to reflect: “While the nation grapples with a form of grief and anger that we have not experienced before, we are seeking answers.”

One answer may be found in the shooter’s rambling 74-page manifesto titled The Great Replacement, apparently inspired by a book of the same title by the French author Renaud Camus. The Great Replacement is a right wing conspiracy theory that claims that white Christian Europeans are being systematically replaced by people of non- European descent, most notably from North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Arab Middle East, through immigration and higher birth rates.

The New Zealand killer’s name is Brenton Harrison Tarrant and his manifesto is filled with white supremacist tropes focused on this conspiracy theory, starting with his opening sentence “It’s the birthrates” repeated three times. “If there is one thing I want you to remember from these writings, it’s that the birthrates must change,” Tarrant insists. “Even if we were to deport all Non-Europeans from our lands tomorrow, the European people would still be spiraling into decay and eventual death.” Tarrant then cites the replacement fertility level of 2.06 births per woman, complaining that “not a single Western country, not a single white nation,” reaches this level. The result, he concludes, is “white genocide.”

This is classic 19th century blood-and-soil romanticism, and the self-described “Ethno-nationalist” Tarrant writes that he went on this murderous spree “to ensure the existence of our people and a future for white children, whilst preserving and exulting nature and the natural order.” His screed goes on and on like this, culminating in a photo collage of attractive white people and well-armed militia men.

It is reminiscent of the “Unite the Right” event in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August of 2017 when white supremacists shouted slogans like “blood and soil” and “Jews will not replace us.” Given that there are only about 15 million Jews in the world, Judaism employs no missionary effort at conversion, and birthrates among Jewish families are among the lowest in the world, why would any group worry about being “replaced” by them? They’re not. They’re reflecting the conspiracy theory that Jews control the media, politics, banking and finance, and even the world economy.

In his manifesto Tarrant references the number 14, or the fourteen-word slogan originally coined by the white supremacist David Lane while in federal prison for his role in the 1984 murder of the Jewish radio talk show host Alan Berg. Here are the 14 words:

“We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.”

The number is sometimes rendered as 14/88, with the 8s representing the eighth letter of the alphabet— H—and 88 or HH standing for Heil Hitler. Lane, in fact, was inspired by Adolf Hitler’s conspiracy- theory laden book Mein Kampf, in which the Nazi leader rants:

What we must fight for is to safeguard the existence and reproduction of our race and our people, the sustenance of our children and the purity of our blood, the freedom and independence of the fatherland, so that our people may mature for the fulfillment of the mission allotted it by the creator of the universe.

Hitler goes on to identify the enemy of his mission— the Jews—which reflects another conspiracy theory called the “stab in the back,” popular in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s. According to this theory, the only reason the Germans lost World War I was that they were stabbed in the back by the “November Criminals” (the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918), who the Nazis insisted were Jews, Marxists, and Bolsheviks.

And this “stab in the back” conspiracy theory itself derives from an earlier and larger conspiracy theory involving The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, a hoaxed document purporting to be the proceedings of a secret meeting of Jews plotting global domination. A number of prominent people at the time believed the Protocols hoax, including the American industrialist Henry Ford, who published his own conspiratorial tract titled The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem. He later recanted and withdrew the book from circulation when he found out the conspiracy theory was a fake.

What all this shows is the power of conspiratorial belief to motivate people to act, including murderous action, from killing dozens in New Zealand to murdering millions in the Holocaust.

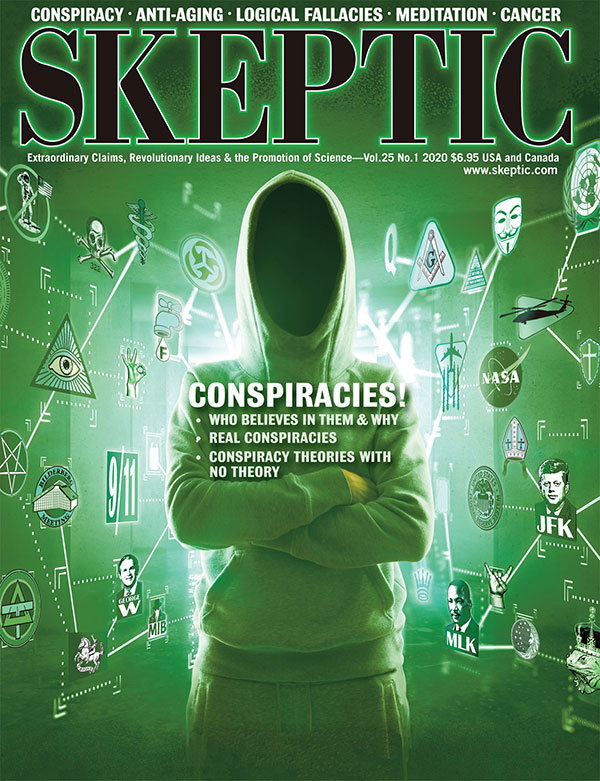

Conspiracy theories are as countless as they are confusing. I once met a politician who told me that he believes the fluoridation of water is the greatest scam ever perpetrated on the public. I have been confronted by 9/11 “truthers” who have insisted the al-Qaeda attack was actually an “inside job” by the Bush administration. Others have regaled me for hours with their breathless tales of who really killed JFK, RFK, MLK Jr., Jimmy Hoffa, or Princess Diana, along with the nefarious goingson of the Federal Reserve, the New World Order, the Trilateral Commission, the Council on Foreign Relations, the Committee of 300, the Knights Templar, the Freemasons, the Illuminati, the Bilderberg Group, the Rothschilds, the Rockefellers, and the Zionist Occupation Government (ZOG) that secretly runs the United States. It would take Madison Square Garden to hold all the conspiracists plotting world domination.

What is a conspiracy, and how does it differ from a conspiracy theory?

I define a conspiracy as two or more people plotting or acting in secret to gain an advantage or to harm others immorally or illegally. I distinguish a conspiracy from a conspiracy theory, which I define as a structured belief about a conspiracy, whether it is real or not. A conspiracy theorist, or conspiracist, is someone who holds a conspiracy theory about a possible conspiracy, again whether or not it is real.

Although the terms “conspiracy theory”, “conspiracy theorist,” and “conspiracist” do sometimes carry pejorative connotations meant to disparage someone or their beliefs—as in “that’s just a crazy conspiracy theory” or “he’s one of those nutty conspiracists”— the terms in fact have a rich history not meant to disparage.

Who believes in such conspiracies? Surveys by the political scientists and conspiracy researchers Joseph Uscinski and Joseph Parent show that conspiracists “cut across gender, age, race, income, political affiliation, educational level, and occupational status.” For example, both liberals and conservatives believe in conspiracies at roughly the same level, although each thinks different secret cabals are at work, with liberals more likely to suspect that media sources and political parties are pawns of rich capitalists and corporations, while conservatives are more likely to believe that academics and liberal elites control these same institutions.

There are other factors at work as well. Race, for example, is not a predictor of overall conspiracism, but it does partially determine which conspiracy theories are likely to be embraced. African Americans, for example, are more likely to believe that the federal government invented AIDS to kill Blacks and that the CIA planted crack cocaine in inner city neighborhoods to ruin them. By contrast, white Americans are more likely to suspect the Feds are conspiring to abolish the Second Amendment and convert the nation into a socialist commune.

Education appears to attenuate conspiracy thinking, with 42 percent of those without a high school diploma scoring high in conspiratorial predispositions compared to those with postgraduate degrees, who come in at 22 percent. Nevertheless, that one in five Americans with postgraduate degrees believe in conspiracies tells us something else is going on here.

In my 2011 book The Believing Brain I suggested that two cognitive processes are at work in conspiracy thinking: (1) patternicity, or the tendency to find meaningful patterns in both meaningful and meaningless noise, and (2) agenticity, or the tendency to infuse patterns with meaning, intention, and agency. I will explore these concepts in more depth in another lecture, but the idea is that the patterndetection filters of conspiricists are wide open, thereby letting in any and all patterns as real with little or no screening of potential false patterns.

Conspiracy theorists connect the dots of random events into meaningful patterns, and then infuse those patterns with intentional agency, and believe that these intentional agents control the world, sometimes invisibly from the top down, instead of the bottom-up causal randomness that determines much of what happens in our world.

To these factors we can add three cognitive biases that often distort events and evidence to fit our preconceived conspiratorial conceptions. For example, the confirmation bias is the tendency to seek and find confirming evidence in support of already existing beliefs, and to ignore or reinterpret disconfirming evidence. Once you have decided that a conspiracy theory is true, your brain sets out to find evidence to support it and filter out evidence that doesn’t.

Another is the hindsight bias, in which we tailor after-the-fact explanations to what has already happened. Once an event has occurred, we look back and reconstruct how it happened, why it had to happen that way and not some other way, and why we should have seen it coming all along, the very essence of conspiracism.

Then there’s cognitive dissonance, the phenomenon of mental tension created when someone holds two conflicting thoughts simultaneously, such as what happens when conspiracy theories about the end of the world don’t come true—instead of admitting their mistake believers double down on their belief and rationalize the failures, all in an attempt to reduce dissonance.

Anxiety, alienation, and feelings of rejection are also factors in conspiratorial cognition. For example, in 2017 Princeton University researchers had subjects write a brief description of themselves that they then shared with two other people in their small group, telling them that they would be judged by the other group members. The subjects who were told that they were rejected were more inclined to believe in conspiracy-related scenarios.

And it’s not just private anxieties. Cultural anxiety may also lead to conspiracy thinking. A 2018 survey of over 3,000 Americans, for example, found that those who reported feeling that American values are eroding were more likely to agree with conspiratorial statements, such as “many major events have behind them the actions of a small group of influential people.”

Feeling in control or powerful in your environment reduces anxiety, but the opposite—concern about what may be out of your control can increase anxiety and conspiratorial paranoia about things that could go wrong. In a 2015 study conducted in the Netherlands, for example, researchers divided subjects into three groups:

- those primed to feel powerless and out of control,

- those primed to feel in control and powerful, and

- a control group not primed for anything.

The subjects were then told about a construction project undergoing problems that could be related to a conspiracy by the city council to steal money from the project’s budget. Subjects primed to feel powerless and out of control were more likely to believe the conspiracy theory. Researchers have also found that conspiratorial speculation runs higher after natural disasters like earthquakes, or when people fear that they may lose their job.

There is another reason why people believe in conspiracy theories that researchers have largely neglected: a lot of them are true. Enough conspiracies are real that it pays to be constructively paranoid because sometimes “they” really are out to get us.

If we take the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of a conspiracy theory as “a belief that some covert but influential agency (typically political in motivation and oppressive in intent) is responsible for an unexplained event,” then even a cursory review of history reveals that conspiracies have dramatically influenced the course of history and may still be found at work in modern societies. Consider some examples.

Julius Caesar was stabbed to death by a conspiracy of Roman senators on the Ides of March in 44 B.C.E.

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 saw a group of provincial English Catholics attempt to assassinate King James I by blowing up the House of Lords during the State Opening of Parliament. The plot was discovered and thwarted days before, with the conspiracists caught, tried, convicted, hanged, drawn, and quartered.

In 1776 an elite group of soldiers were assigned to be George Washington’s bodyguards, some of whom were plotting to assassinate the future first president of the United States at the behest of the governor of New York and the Mayor of New York City. The plot was foiled, thanks only to the ineptitude of the plotters to keep a secret.

Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by a conspiracy of Southerners angered by the outcome of the Civil War, which itself was instigated by a Southern cabal to illegally secede from the United States—arguably the biggest conspiracy in U.S. history.

World War I exploded after a Serbian separatist secret society called the Black Hand conspired to assassinate the Austrian archduke Franz Ferdinand, leading to an arms race that erupted in the guns of August and the start of a conflict that resulted in the deaths of millions.

The Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor was, by definition, a conspiracy that the U.S. military and intelligence agencies failed to detect, leading to conspiracy theories that President Roosevelt let it happen on purpose to drag America into war.

The obsessively paranoid Joseph Stalin wasn’t conspiratorially-minded enough to realize that Hitler was plotting to break their nonaggression pact and invade the Soviet Union, despite warnings from the British government to that effect. The consequence was the deaths of tens of millions of soldiers and civilians.

In the 1950s, with his now-infamous Congressional hearings, the conspiratorially minded Senator Joseph McCarthy launched a witch hunt to ferret out what he claimed was a Communist conspiracy to destroy America.

In the 1960s, Operation Northwoods was a document produced under the Kennedy administration that proposed a number of “false flag” operations that might be carried out in order to justify military intervention in Cuba. Among the proposals were such ideas as staging a fake attack on the U.S. military base at Guantanamo Bay, employing a fake Russian MiG aircraft to buzz a real U.S. civilian airliner, faking an attack on a U.S. ship to make it look like Cubans did it, and developing “a Communist Cuban terror campaign in Miami.” None of these crazy ideas were implemented, but that members of Kennedy’s administration considered them—even in the context of a meeting with people just spitballing ideas willy nilly—reveals the lengths to which even high ranking people in the government are willing to conspire against others to get their way.

In the 1970s, Watergate stands out as a conspiracy of dunces, and the Pentagon Papers revealed the extent to which the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations conspired to escalate the Vietnam war without Congressional knowledge, much less approval. And we now know that Kennedy conspired to have Fidel Castro assassinated, Johnson conspired to cover up that fact when he took office, and Nixon secretly recorded conversations in the Oval office that revealed his distinctive view of presidential power—a view that he later summarized in an interview with David Frost as follows: “Well, when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal.”

In the 1980s, the Iran-Contra arms-for-hostages scandal was a conspiracy that embodied what conspiracists since World War I had been concerned about—the usurpation of power by conspirators who were legally elected to their positions instead of hijacking government agencies through a coup, which was common in centuries past.

In the 1990s, government overreach against Randy Weaver and his family in Ruby Ridge, Idaho, and against David Koresh and the Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas, understandably led to the rise of the conspiratorially-minded militia movement that culminated in Timothy McVeigh’s bombing of a federal building in Oklahoma City.

In the 2000s, the George W. Bush administration concocted a conspiracy theory that Iraq was developing weapons of mass destruction as a justification for invading that country, which proved false when inspectors failed to find any WMDs. And Wikileaks revealed the extent to which the NSA and other governmental agencies conspired to spy on Americans and foreign leaders on the heels of 9/11. As Buffalo Springfield cautioned in their 1966 hit song For What It’s Worth, “There’s something happening here. What it is ain’t exactly clear.”

In the 2010s, as if the run-up to the 2016 Presidential election wasn’t crazy enough, in the middle of it, and continuing after Trump’s victory, there emerged a bizarre conspiracy theory at Trump rallies were some of his supporters held signs reading “Q” and “QAnon.” It apparently began with an internet user called “Q Clearance Patriot” or “Q,” who posted on internet message boards like 4chan and 8chan the conspiracy theory that inside the “deep state” there is an “anonymous” source working against the Trump administration. “I can hint and point but cannot give too many highly classified data points,” the Q conspiracist wrote, adding: “These are crumbs and you cannot imagine the full and complete picture.” That complete picture apparently includes such operatives as Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, George Soros, and various Hollywood celebrities, all alleged to be involved in a global sex trade and pedophile ring.

The “Qincidences” (spelled with a Q) include the recurrence of certain numbers, such as 17 (Q is the 17th letter) and 4, 10 and 20, corresponding to DJT, or Donald J. Trump. And since “there are no coincidences” in the mind of the conspiracist, such numerology led to the absurd 2016 “Qonspiracy theory” (also spelled with a Q) of “Pizzagate”. Promulgators of this theory asserted— without any evidence and beyond belief—that Hillary Clinton was directing a pedophile ring out of a pizza parlor. As absurd as this sounds, the Pizzagate conspiracy theory led a young man to shoot up a restaurant with an AR-15-style rifle, claiming he intended to break up the perceived perversion. It was fortunate no one was hurt in the incident, but it revealed the power of conspiratorial paranoia.

As we approach the 2020s a new type of conspiracism has been identified by the political scientists Russell Muirhead and Nancy L. Rosenblum in their 2019 book, A Lot of People are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy. Classic conspiracy theories are grounded in arguments and evidence, whereas more recent conspiracy theories are simply asserted, usually without facts to support them. This new conspiracism is captured in the book’s title, ripped from the 2016 presidential election and Donald Trump’s recurrent phrase “a lot of people are saying,” which was typically followed by no evidence whatsoever for the assertion. As Muirhead and Rosenblum explain the new conspiracism:

There is no punctilious demand for proofs, no exhausting amassing of evidence, no dots revealed to form a pattern, no close examination of the operators plotting in the shadows. The new conspiracism dispenses with the burden of explanation. Instead, we have innuendo and verbal gesture: “A lot of people are saying …” Or we have bare assertion: “Rigged!” … This is conspiracy theory without the theory.

How then does such conspiracism spread and catch hold? Repetition. In the age of social media, what counts is not evidence so much as retweets, re-posts, and likes. And by no means is the new conspiracism the product only of President Trump, given that politicians—not to mention economists, scholars, pundits, and ideologues of all stripes— have been making evidence-lacking assertions for generations, although admittedly without an audience of 60 million twitter followers the current conspiracist-in-chief commands.

More importantly, Trump’s conspiratorial assertions would go nowhere without a receptive audience, so the blame for the nefarious effects of the new conspiracism have to be spread much wider to encompass all of social media, alternative media, and even some mainstream media, which have stepped up their sensationalistic headlines in an effort to recapture advertising dollars they’ve been losing since the rise of the Internet.

Individuals act on their beliefs, and when those beliefs contain conspiracy theories about nefarious goings-on, those acts can turn deadly. That is exactly what happened at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh on October 27, 2018, when an assailant armed with guns and one of the oldest conspiracy theories about the Jews running the world, murdered eleven congregants before his capture. “I just want to kill Jews,” he proclaimed.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 25.1

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Consuming content on the online social network Gab, the conspiricist grew paranoid about the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), which the Tree of Life synagogue helped support. On Gab the conspiracist read that HIAS provided aid to the migrant caravans moving north from Central America toward the United States’ southern border. “HIAS likes to bring invaders in that kill our people,” the assassin posted on Gab just before he committed the mass murder, adding “I can’t sit by and watch my people get slaughtered. Screw your optics, I’m going in.”

This brings us back to the mass murder in New Zealand with which we began this lecture. These are just two of countless conspiracy theories with real-world consequences, mostly bad. Ideas matter. Beliefs matter. Conspiracy theories matter. And they are not confined to the fringes of pop culture or the dark web, but instead penetrate all areas of public and private life, often directing the lives of people and the course of history.

So as we analyze examples like these in the lectures ahead, I hope you’ll reach the same conclusion that I’ve reached: The subject of this course—conspiracies and conspiracy theories— could well be one of the most important subjects any of us can study. ![]()

About the Author

Dr. Michael Shermer is the Founding Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of the Science Salon Podcast, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University where he teaches Skepticism 101. For 18 years he was a monthly columnist for Scientific American. He is the author of New York Times bestsellers Why People Believe Weird Things and The Believing Brain, Why Darwin Matters, The Science of Good and Evil, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His new book is Giving the Devil His Due: Reflections of a Scientific Humanist.

This article was published on July 17, 2020.

You just lost all credibility with this article. I guess even the skeptic requires a skeptic. Events 12,000 years ago are one thing but events unfolding before our very eyes is another.

The study did not include religious affilaiations, views or indentities. For Christians it is almosted mandatory to hold a grand conspiracy view. Preterists may be excluded but the reality of history follows Rome and Jerusalem as a conspirators in the death of Christ. So the obvious targets of CT fall to Tamudic Kabbalah Jews and “Templar” Jesuits.

Evidence is readily available to read about the connections of these powerful forces over time and their ascension to power. In the US, from it’s constitution forward allowed no Catholic to run it’s highest office until JFK and that was the birth of the CIA’s “Mockingbird” was in full swing. It included creating conspiracy theory as a tool to marginalize, dismiss and reject alternate theory and investigation. Along with MK-Ultra, Monarch and other covert ops in history and the findings of the study, one could suggest the education system as the foundation for a certain amount of brain-washing.

Adding that ‘fake news’ is nothing new and looking at the history of publishing and media in the few hands of power elites you find similar evidence of the enormity of disinformation and cointelpro that one must accept as truth. When it became important to raise the bar and stakes, Barack Obama repealed the Smith-Mundt Act. There is a smoking gun if ever there was one. No offense but the academics and powers that be cannot refute their confederation. Take a look at Jewry in corporate, banking and media and look at Jesuit schooled heads of State throughout the EU, US, Canada, Indonesia and Australia.

Random?

There’s a false equivalence here:

“…liberals [are] more likely to suspect that media sources and political parties are pawns of rich capitalists and corporations, while conservatives are more likely to believe that academics and liberal elites control these same institutions.”

The former position is objectively true: most media sources are corporations (e.g. Fox, NewsCorp, DMG Media, etc.) owned by rich capitalists (with some exceptions, such as the BBC in the UK), and wealthy corporations and individuals do <ahem> ‘make campaign contributions’ to politicians and parties.

In contrast, no media sources are owned or controlled by academics – even most academic journals are owned and controlled by corporate, capitalist publishing houses (although some are published by learned societies). Some ‘liberal elites’ may make donations to politicians and/or parties, but to nowhere near the extent as capitalist corporations and corporate lobbyists.

To equate the ‘liberal’ view, which is objectively true, with the ‘conservative’ view, which is objectively false, is not an honest, skeptical position to take.

Excellent article. In my mind it seems to skip around the dilemma of facts at the heart of conspiracy theories. You named a series of accepted happenings which can be considered actual conspiracies. How do we separate the reality from the fanciful? If a small group of individuals have a bit of power or wealth and wish to maintain or increase their standing, do their actions towards that goal not constitute a conspiracy? How can their actions be realized as self serving, without it being branded as being part of a “grand conspiracy”, and still be judged and reacted to by those whom it affects? Specifically, may I not infer the goals of a media empire as being politically motivated, without me being considered a conspiracy theorist? This concerns me greatly due to watching what is transpiring now. I don’t believe in grand conspiracies but I do know people in power can wield that power and do so to their own end.

RE How do we separate the reality from the fanciful?

Evidence. Some of the actual conspiracies were uncovered by analyzing documents and personal accounts. Others were uncovered by direct observation (e.g. searching Iraq for WMDs).

You point out a central problem with imaginary conspiracies, that they may be hard or impossible to disprove. All you have are lack of evidence and Occam’s razor.

A very interesting and extremely relevant reference point. Your opening example of the NZ massacre by an Australian is most concerning personally as I am an Australian. Sad to say we in this wide brown land possess many conspiracists who are often quite high profile and even leaders in our parliamentary system. And with reference to the apparent belief that evidence is no longer considered a requisite it might be said that the term “Fake News”

has replaced any requirement for tangible evidence.

While not your central issue it was interesting to note the reference to racial “preservation” as being a motivator for conspiracy theories. Interesting because a recent study on population growth predicts that low birth rate will bring the current spiral of population to a standstill at c.10.5 billion by 2070 and that most European countries will halve their population, that China will decline to c.500 million and that the

likelihood that the only growth will come from sub-Saharan Africa

with the population reaching something like 3-3.5 billion.

Now what will the conspiracists derive from such a prediction