Here are a few small studies you can do on your own to introduce this column’s subject:

- Sit in a coffee shop and watch people who are eating together. Count how many times one person touches the other as they converse. If you live in a large city, you should have a wealth of diverse individuals to observe; if your coffee shop is monocultural, you might have to do a little traveling. Many years ago, Sidney Jourard did this in San Juan (Puerto Rico), Paris, London, and Gainesville (Florida).1 His scores were: San Juan, 180; Paris, 110; London, 0; and Gainesville, 2.

- Examine the photos of survivors of any horrible event—a natural disaster, such as flood or fire, or a human-made disaster, such as a mass shooting or bomb. Try to find an image of survivors standing apart from one another, arms crossed in front of them. You can’t, can you? Total strangers as well as neighbors will be hugging each other, whether stoically or in tears, for comfort and support.

- If you can find some little kids to watch, your own or anyone else’s (or if you remember being a little kid yourself), observe what they typically do when they fall and hurt themselves, have a scary nightmare, or feel lonely: run to a loved adult for a comforting cuddle.

- Listen to what people say when a gift or experience moves them emotionally and when they reconnect with old friends: “I’m touched,” they say, and “I’m sorry we lost touch.” Notice they don’t say “I’m hearing” or “I’m sorry we lost smell.” What is the touch that has touched them?

- Observe all the signs in museums that say “don’t touch.” If touching were not a natural impulse, why tell us repeatedly (and often uselessly) not to do it?

Touch is the often the last, but not the least, of what are considered the five basic senses, following vision, hearing, smell, and taste. But it is just as crucial for human survival; the need to touch and be touched emerges the minute a baby is hatched. Babies are born with a grasping reflex—they will cling to any offered finger—and it’s abundantly clear, from the pioneering research of the British psychiatrist John Bowlby and the psychologist Harry Harlow, that babies crave as much “contact comfort” as they can get. Infants who get little touching and cuddling will grow more slowly and release less growth hormone than their amply cuddled peers, and throughout their lives, they will have stronger reactions to stress and be more prone to depression and its cognitive deficits.2 Babies who are raised with “creature comforts” but not contact comfort may be physically healthy but emotionally despairing, remote, and listless.

The pleasure of being touched and held, and of touching others, is crucial not only for newborns, but also for everyone throughout life, because it releases a flood of pleasure-producing and stress-reducing endorphins. It calms the stress response we feel after tragedy, loss, or fear. In hospital settings, even the mildest touch by a nurse or physician on a patient’s arm or forehead is reassuring psychologically and lowers blood pressure. Gestures emerge in infancy, before speech, and touch and gestures remain a central part of human communication: we touch to say hello and goodbye, to warn, to sympathize, to express affection, to be reassured, to get attention, and, most of all, to feel connected.

Tiffany Field, director of the Touch Research Institute at the University of Miami School of Medicine, and her lab have been studying the physiology and psychology of touch for decades. Among their important findings: American preschoolers are touched less than French children, American adolescents touch each other less than French teenagers do, and— though causality can’t be strongly determined—American children of all ages behave more aggressively toward their peers than French preschoolers and adolescents. But Field’s research shows that “massage therapy” helps everyone by lowering blood pressure and improving immune function, and has special benefits for target groups—infants, pregnant women, people with HIV, children with autism, patients suffering fibromyalgia pain. A laying on of hands literally, not just religiously, soothes and heals. For that reason, the current medical experience for most patients— in which the doctor spends most of his or her time entering their data into a computer, barely looking at, let alone touching, the poor worried patient sitting there—is not only over-tech, it’s under-human.

To be sure, the human need for touch, like every other aspect of human behavior, is profoundly affected by culture, gender, learning, and the individual’s own temperament. Some individuals are touch-averse, and so are some entire cultures. In his classic book Touching: The Human Significance of the Skin, anthropologist Ashley Montagu noted that “There are whole cultures that are characterized by a ‘Noli me tangere,’ a ‘Do not touch me,’ way of life. There are other cultures in which tactility is so much a way of life, in which there is so much embracing and fondling and kissing it appears strange and embarrassing to the nontactile peoples.”3

Much of American culture falls into the category of “nontactile peoples”— Gainesville, 2!—and those who suffer most from this cultural norm are men. Many males grow up thinking that touch has only two functions: sex and violence. Touch is for grabbing a woman by the pussy or punching another guy on the nose; any other kind of touching—certainly male-male affectionate touching—is evidence of being “feminine,” gay, or weak. Look how hard it was for Andrew Reiner to say farewell to his dying father with a loving gesture of touch:

I had thought about reaching for my father’s hand for weeks. He was slowly dying in a nursing home, and no one who visited him…held his hand. How do you reach for something that, for so many decades, hinted at violence and, worse, dismissal? … I finally did it. I touched my father’s hand, which I hadn’t held since I was a young boy. His curled fingers opened, unhinging some long-sealed door within me, then lightly closed around mine. Before I left, I did something else none of the males in my family had ever done before. I leaned close to my father’s ear and whispered, “I love you.”4

After the brief flutter of a “sexual revolution” in the 60s and 70s, which explicitly encouraged the breaking down of touch barriers, tactility took a major hit in the 1980s and 1990s, in the wake of the nationwide panic over nonexistent pedophiles in daycare centers and the entirely-too-existent pedophile priests. Almost overnight teachers and other adults were forbidden to touch children in any way, even to comfort little ones with scraped knees. And even when not officially forbidden, many adult men stopped touching children to comfort them, fearing that their caring gesture would be misunderstood by suspicious passersby. Today, in the aftermath of “#MeToo,” touch has taken another hit, as many men worry about friendly, platonic touches of their female friends and colleagues; will these be construed as inappropriate, sexist power ploys?

I got to thinking wistfully about Ashley Montagu and Tiffany Field after reading a news story about the students at Antioch College and their latest crusade on behalf of rules for sexual consent. Having pioneered a policy of “affirmative sexual consent,” since adopted at colleges across the country, Antioch students, the reporter wrote, “are moving the conversation beyond sex to discussions of consent in platonic touch.”5 At Antioch now, you don’t tap someone on the shoulder to get their attention; you ask permission for shoulder tapping. You don’t impulsively hug a friend; you get consent first. Even your mother has to get your permission. When one thirdyear student came home for her first visit after starting college, she told the reporter that she was taken by surprise when her mother hugged her. “If you don’t want to be touched and your mom wants to hug you, you should be allowed to say no,” the student said proudly. “It’s about having autonomy over your own body.”

She was taken by surprise? A loving hug is now a surprise? Sure, no one should have to submit to unpleasant squeezes and slobbery kisses and unwanted hugs—from relatives, dates, strangers, or coworkers. But “your own body” doesn’t only want autonomy; it also craves community and connection with other bodies. The constant refrain of “me, me, me” drowns out “us” and smothers empathy. Maybe this student’s mother is a toxic hugger, but maybe she just loves her daughter, freshly home from college, has missed her desperately, and simply wants, well, a hug. How about thinking of your mom’s feelings for 30 seconds, Ms. Autonomous Student? How about considering the cost of relentless consentseeking— the loss of spontaneity, a joyful sharing of a moment of affection and intimacy, a touch on a nervous friend’s arm to convey reassurance?

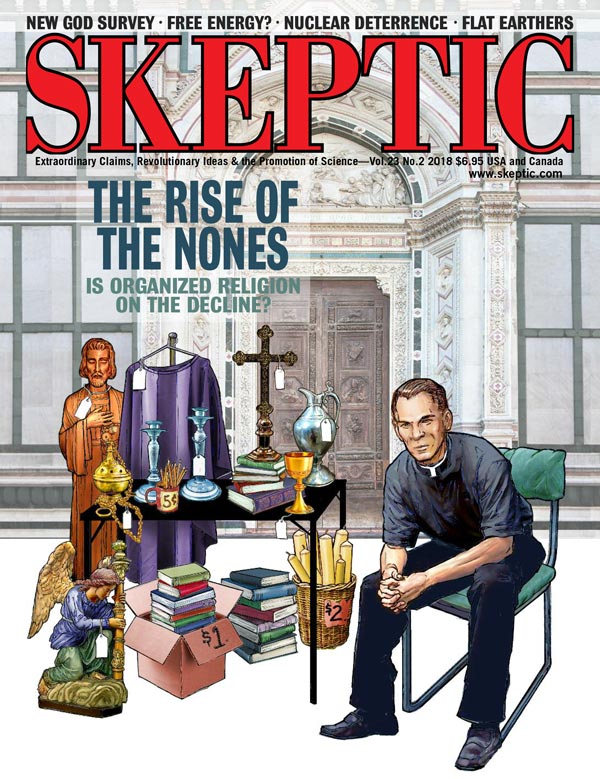

This column appeared in Skeptic magazine 23.2

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

I appreciate how conflicted and unsettled many men are these days, not knowing which gestures, embraces, or touches a female colleague will regard as welcome or as unwelcome. The difference is abundantly, nonverbally clear to me and I think to most women, but it obviously is not clear to the many men who think that touch = sex and only sex. Therefore, the solution is obvious: for men to learn to appreciate the joys and benefits of nonviolent, nonsexual touch, they need to start practicing on other men: their brothers, their sons, their friends…their fathers. ![]()

About the Author

Dr. Carol Tavris is a social psychologist and coauthor, with Elliot Aronson, of Mistakes were made (but not by ME). Watch the recording of Science Salon # 10 in which Tavris, in a dialogue with Michael Shermer, explores cognitive dissonance and what happens when we make mistakes, cling to outdated attitudes, or mistreat other people.

References

- Jourard, Sidney. 1996. “An Exploratory Study of Body-accessibility.” British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 114, 135–136.

- Field, Tiffany. 2009. “The Effects of Newborn Massage: United States.” In T. Field et al. (Eds.), The Newborn as a Person: Enabling Healthy Infant Development Worldwide. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Montagu, Ashley. 1986. Touching: The Human Significance of the Skin. (3rd ed.) New York: Harper, 1986, p. 292.

- Rosman, Katherine. 2018. “Thank You for Asking.” The New York Times, Feb. 24.

- Reiner, Andrew. 2017. “The Power of Touch, Especially for Men.” The New York Times, Dec. 5.

This article was published on January 1, 2019.

I agree that touching and hugging is essentially healthy, but I have a problem with being touched because I have PTSD. More than once when tapped on the shoulder or upper left arm I’ve gone into hypervigilant attack mode. Fortunately I’ve never been discharged from a job or gotten in trouble with the law and only once have I actually hit anyone, but two occasions I’ve been accused of “disruptive” and “aggressive” behavior, and most outrageously, was taken to task for upsetting and scaring the person who set me off in the first place. With the exception of parents, co-parents, extended family, longtime friends and significant others, I would admonish people to ask before hugging, patting or otherwise putting their hands on another person.

Thanks for this good little article.

I’m presently a 72 year old male and have been a “toucher” since my late 20s. (It took me that long to allow myself to out grow my childhood upbringing once I found myself in a more relaxed cultural setting.) I am lucky to have not ever gotten myself into a awkward situation of any consequence as I frequently touch men and women on the shoulder as sign of parting or greeting. I am delighted when people come up and hug me, but in this day and age I am wary of hugging others who I do not know well.

One thing that I am grateful for is becoming a toucher before I was a parent. Our children are totally comfortable with touching and and hold, hug, and cuddle our young grandchildren constantly to no one’s objection.

Thank you for this important contribution to an increasingly difficult subject, Dr. Tavris. As an old, white male, raised by post-WWII parents who had been led to believe that touching a baby or child would spoil him or her, let me confirm that the lack of such contact in childhood is deeply damaging to the later adult. Try as you may, you cannot make up for this gap in your experience, and it never becomes easy to break down this learned resistance to being touched, even by a loved one, however much you want to.

Regarding the final thought in your piece: As an old American male, I clearly sense how tough it is to change, keeping up with society’s morphing “norms.” I grew up sensing that touching behavior in males was a sure sign of weakness.

I suspect “touch,” as body language is, like verbal language, most easily learned and absorbed as a young child… being progressively more challenging with age…

A beautifully written essay, Dr. Tavris! (I was tempted to say, “touching” but didn’t want to diminish the sincerity of my feelings)