In its 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision the United States Supreme Court (SCOTUS) overturned the previous court decisions on abortion rights in Roe v. Wade (1973) and Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992). The 5–3 majority opinion stated that the substantive right to abortion was not “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history or tradition,” nor considered a right when the Due Process Clause was ratified in 1868, and was unknown in U.S. law until Roe. (Chief Justice Roberts issued a separate Concurring Opinion).

The Dobbs decision has transferred the relevant issues on personhood and abortion rights to legislatures for resolution, whether they be state or federal.1, 2 So, unless one political party manages to dominate the federal government and Congress passes and the president signs a federal abortion law, each state is free to pass its own abortion law. In states where abortion is prohibited or severely restricted, some women who wish to end their pregnancies will have to travel to other states or even to other countries to get proper services, while others may even seek possibly unsafe “underground” abortions in their own states. The best solution to the ensuing inefficient, irrational, and dangerous patchwork of laws would be a reasonable and comprehensive abortion law passed by the federal government applicable to all 50 states. This essay presents not only a model for that law, but also offers a philosophical and scientific foundation upon which to base it.

Warring Camps

For the last 50 years views on abortion rights have been polarized in two warring camps—pro-life and pro-choice. Those taking the extreme in the pro-life position argue that a soul is inserted in the human organism at conception, that the organism becomes a person at this time and so possesses full human rights, and therefore abortion is immoral, equivalent to some degree of murder, and so should be illegal with no or few exceptions. Those taking an extreme pro-choice position argue that the human organism becomes a person only when it is removed from the mother and takes its first breath and that abortion, although regrettable, is morally acceptable and should be legal with no or few exceptions.

Each of these extreme positions, I submit, is irrational. For example, there is no good evidence for the existence of a soul or even for any god’s insertion of a soul at the exact moment of conception. As such, pro-life advocates believe that couples should have no right or opportunity to correct reproductive mistakes or contraceptive failures through the method of abortion. Pro-choice advocates, on the other hand, believe that the mother is either morally infallible in making decisions about abortion or should always be provided with “abortion on demand” even if she makes a moral mistake. These pro-choicers typically believe that nobody has any business in considering, discussing, or participating in abortion decisions except for the mother and her doctor. Many pro-choice radicals even totally exclude men from the abortion discussion, including male legislators and the male partner/father. These extreme positions are unreasonable and counter-productive.

Terminology

Unfortunately, during the past half century, as the pro-life and the pro-choice factions have battled each other, relevant terminology has suffered. Pro-life advocates have been particularly egregious in using inaccurate, unscientific, misleading, and propagandistic terms. For example, in her article in the special issue of Skeptic on abortion matters, Danielle D’Souza Gill continually referred to human organisms inside a woman as “the unborn.”3 Any living human organism inside a woman, however, has three possible outcomes—death in the womb or miscarriage, abortion or premature delivery, and birth or mature delivery. In fact, the first outcome is more likely than the other two.4, 5 So, why not call the indwelling organism “the unmiscarried”? Or to be more accurate, why not call it “the unmiscarried/unaborted/unborn”? Why does Ms. Gill and other extreme pro-life advocates insist upon the term “the unborn”? Because their goal is for every single one of these human organisms to be born, even if that goal were to be opposed by any individual woman who seeks an abortion. These radicals wish to impose their values, goals, and moral rules on all women through relevant laws and SCOTUS decisions. In their minds, every zygote is sacred.

Ms. Gill also referred to these indwelling human organisms as “babies.” Why does she do that? Because even though a human organism in the womb is certainly not a baby, she and her cohorts wish to emphasize the similarities of the zygote, embryo, or fetus to a baby, all in furtherance of their political agenda. (By “embryo” I mean an immature multi-celled human organism, from conception through eight weeks post conception. And by “fetus” I mean an immature multi-celled human organism with all prototypical organs and tissues, from nine weeks post conception until birth.) The worst abuse of language in this regard occurs with use of the terms “unborn baby” and “unborn child.” What’s next? Are adults “undead corpses”? Such language distortion does not constitute a valid philosophical argument for the pro-life position.

Any fair and accurate analysis and any reasonable ethics and legislation on abortion should disregard all the propaganda terms and use clear, accurate, and/or scientific terminology. Much follows from precise language.

To Codify or Not to Codify?

Most pro-choice advocates, even the current president of the United States, support the passage of a new federal law that would codify the 1973 SCOTUS decision of Roe v. Wade.6 This would be a huge mistake. That decision was poorly conceived and articulated. Even the distinguished Supreme Court liberal, nominated by a Democrat President, the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg thought so.7 In the Roe decision, later reinforced by Planned Parenthood v. Casey in 1992, the high court established a right to abortion on the crude insubstantial concepts of trimesters, viability, and privacy. It is convenient that 39 weeks, the length of a typical pregnancy, is divisible by three, but that’s a rather arbitrary fact on which to craft a SCOTUS decision on abortion.

Viability is an unreliable measure since it depends so much on specific medical technology and geography. A fetus viable at Cedars Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles would almost surely not be viable in a clinic in a remote village in Africa or even rural West Virginia. Further, people ought not be able to hide a harmful, unethical, and/or illegal act by claiming privacy. For example, secrecy ought not be a shield for murder, and as we know, radical pro-life advocates have long claimed that abortion is murder. Although overall, the Roe decision had beneficial effects on American society, the decision itself was poorly formed, and this might be one reason why it ultimately failed. A new federal law must improve upon the Roe decision, not simply copy or codify it.

A new morality, federal law, and/or SCOTUS decisions on abortion should discard old concepts such as trimesters, viability, privacy, and an absolute right to abortion on demand, and instead should be grounded in rational concepts such as personhood, rights to bodily autonomy, life, well-being, property, parental protection and supervision, and contracts. They should be precisely defined using unbiased terminology and grounded in the science of reproduction. Roe and Casey are obsolete and now invalidated. We need something stronger, more rational, and better articulated to put in their place.

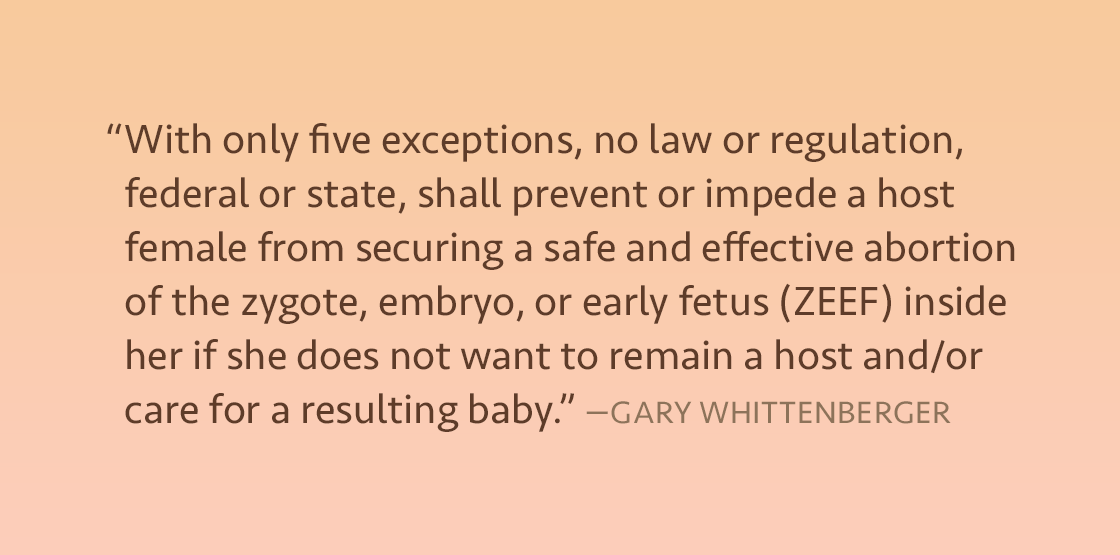

The Default

With only five exceptions no law or regulation, federal or state, shall prevent or impede a host female from securing a safe and effective abortion of the zygote, embryo, or early fetus (ZEEF) inside her if she does not want to remain a host and/or care for a resulting baby. Thus, a robust right to abortion would be established as the default. This right to abortion is subsumed under a universal right to bodily autonomy. Here are the five exceptions to this robust right.

Exception 1: A host female seeking an abortion shall be required to obtain the procedure only from a licensed competent medical professional and shall be prohibited from obtaining one from unlicensed or incompetent service providers or those belonging to some “underground black market.” Abortions are relatively safe, even safer than pregnancies maintained to full term, when performed by competent and licensed medical staff.

Exception 2: A host female seeking an abortion shall be prohibited from obtaining the procedure if the ZEF inside her is a fetal person, except for good reasons of which there are only five. Pro-life advocates are correct on the importance of defining what a “human person” is. Federal and state laws and constitutions are mostly formulated to refer to persons, outlining what persons may or may not do and what rights persons have. The problem, however, is that pro-life advocates have always proposed irrational, unfounded, arbitrary, or ridiculous definitions of a “human person.” A cluster of cells shortly after conception is not a human person.

A human person is any living organism belonging to the species Homo sapiens that has acquired and currently possesses the capacity for consciousness, usually beginning at the end of the 24th week post conception. Since the brain is the organ that distinguishes humans from other animal species, it is absolutely essential that “human person” be defined by some emergent feature of the brain. Consciousness is the key feature, since other cognitive abilities and traits either depend on consciousness or are closely related to it. When the fetus becomes conscious for the first time, it then learns something for the first time, namely, what it’s like to be a human organism. Elsewhere, I have provided the full philosophical and scientific justification for this definition,8 so I will not repeat it here. Suffice it to say that a zygote, embryo, and early fetus are not persons by this precise definition, regardless of any similarity in gross appearance to a baby. Rights are assigned to persons, not nonpersons or potential persons.

Pro-life advocates do not take notice of the differences of categories such as human life, human organism, and human person. A single sperm, a single egg, or a living cell from any part of the human body is human life, but these are not human persons; they aren’t even human organisms. A zygote, embryo, and early fetus are clearly human organisms, but they still aren’t human persons because they lack the critical capacity for consciousness. Rights should be reserved for human persons. Jay Watts, a Christian pro-life advocate, asserts: “Any successful defense of abortion must define the unborn as less meaningful life.”9 True. The lives of zygotes, embryos, and early fetuses are indeed less meaningful than fetal persons and the women carrying them. Meaning and value are added or attributed once the human fetus acquires the capacity of consciousness.

When a fetus becomes a human person in the womb, it then acquires human rights just as the host female possesses those rights, and the most important rights for the fetal person are the rights to life, well-being, and parental protection. The host female should not be entitled to endanger these rights of the fetal person through abortion for frivolous or arbitrary reasons. She should have a “good” or a rational reason before being allowed to abort the person inside her. These reasons include:

- To protect the host female from death.

- To protect the host female from permanent injury.

- To protect the host female from unbearable intractable pain or suffering.

- To protect the fetal person from intractable pain or suffering.

- To hasten the death of any fetal person who is so damaged, disordered, deformed, or ill that it is less likely than not to survive for at least two years even with the best medical technology.

All other reasons presented to abort a fetal person shall be considered to be “bad” reasons and thus insufficient grounds to proceed with an abortion. These reasons include:

- “I’ve just changed my mind.”

- “I can’t stand this pregnancy anymore.”

- “I want to return to college.”

- “This baby came from a rape.”

- “My fetus has Down’s Syndrome.”

On the other hand, reasons that are bad, irrational, and insufficient to abort a fetal person may be rational and sufficient to abort a ZEEF (zygote-embryo-early fetus), and they usually are.

If a fetal person and its host female have equal rights to life, well-being, and liberty, then why should the host female be permitted to have an abortion whenever this act would harm the fetal person more than retention of the fetus would harm the host female? However, in conflict situations in which harm to the two is likely to be equal under opposite decisions, then it makes sense to give priority to the host female.

Prior to the fetus becoming a human person, a host female shall be entitled to get an abortion for almost any reason at all, although there are a few exceptions noted below. These reasons include:

- Pregnancy from rape, incest, or sexual trafficking.

- Already have enough or too many children.

- Lack of a partner or other social support.

- Lack of income, savings, or a job.

- Physical, mental, or drug problems.

- Severe defect, disease, or disorder in the ZEEF.

- Pregnancy too uncomfortable or risky.

- Insufficient parenting skills.

- Change in career plans.

- Strong social disapproval of pregnancy.

- Being abandoned by the male partner or one’s parents.

- Recent death in the family.

- Unplanned pregnancy from casual sex.

Exception 3: A surrogate female shall be prohibited from obtaining an abortion except for any reason stated in her written contract or otherwise for any of five good reasons, the same as those stated in exception 2. Persons should always keep the contracts, agreements, or promises they make, as long as those requirements are ethical and legal from the outset. Surrogate agreements almost always meet these standards.

Exception 4: A host female shall be prohibited from obtaining an abortion if she agreed with her male partner prior to sexual intercourse that she would not get an abortion and would retain the ZEF to full term, unless she has any of five good reasons to abort, as stated in exception 2. As stipulated above, persons should always keep the contracts, agreements, or promises they make, as long as those requirements are ethical and legal from the outset. (For these important agreements related to sexual and reproductive behavior, I favor their real-time documentation through a dependable standard cell phone application, given the ubiquity of these tiny pocket computers.)

So many disputes, conflicts, and controversies regarding sex, abortion, reproduction, and children could and would be avoided if couples would just have open and honest discussions and make critical decisions before having sexual intercourse. A male partner and a female partner have a moral duty to always discuss and come to an agreement on key issues before they have sexual intercourse. These include:

- Having sexual intercourse at all.

- Verbal or gestural signals to stop the intercourse in progress.

- The use of any contraceptives and by whom.

- The disposition of any resulting ZEEF, either retention or abortion.

- Caretaking responsibilities for any baby potentially resulting from intercourse.

If they cannot reach agreement on these issues, then they simply should not have intercourse. Of course, such discussions may temporarily attenuate passion, but making these advance agreements is likely to reduce unwanted pregnancies and abortions. And romantic feelings can be rekindled after such conversations. In general, it would be wise to have at least a 12-hour waiting period between the discussions/decisions and the sexual activity.

If such conversations do not happen and a woman becomes aware that she is pregnant, she should disclose this fact to her male partner and then discuss and decide with him the disposition of the ZEEF. The male partner has a right to know about the pregnancy and participate in the decision. Why? Because both parties are equally responsible for the existence of the human organism residing in the female partner. However, there is an exception to this disclosure: if the pregnancy is a result of rape, incest, or sex slavery.

Exception 5: A host female shall be prohibited from obtaining an abortion if she and her male partner made no agreement regarding abortion prior to sexual intercourse, the male partner objects to the abortion, and a court approves a proper plan for the male partner to take full parental responsibilities for a resulting baby, unless the woman has any of five good reasons to abort, as outlined in exception 2.

In this case, since the male and female partners failed to discuss and decide what to do with a ZEEF—either abort it or retain it—before they had intercourse, then they must engage in this discussion as soon as the female informs her male partner that she is pregnant. Most outcomes are easy to determine:

- If both female and male partners vote for retention, then the ZEEF shall be retained and both parties shall equally share the caretaking responsibilities for the resulting baby, unless they both agree to put the baby up for adoption at birth.

- If both female and male partners vote for abortion, then the ZEEF shall be aborted.

- If the female partner votes for retention and the male partner votes for abortion, then the ZEEF shall be retained, and the female partner shall assume all caretaking responsibilities for the resulting baby. The male partner shall have none of those responsibilities nor visitation rights with the baby.

- If the female partner votes for abortion and the male partner votes for retention, then the ZEEF shall be retained or aborted depending on the unique circumstances. If either partner used contraception, then the intentions of the couple were clear—they didn’t want to produce a ZEEF, a fetal person, or a baby. Therefore, in these circumstances, the vote of the male partner for retention should be disregarded and the ZEEF should be aborted. If neither partner used contraception during intercourse, then the intentions of the couple were unclear and ambiguous. In this case the vote of the male partner for retention should be honored, the ZEEF should be retained, and the male partner should assume all caretaking responsibilities for the resulting baby, contingent on a court-approved plan. Even if the male’s plan for retention of the ZEEF is already approved and/or implemented through the court, the host female must be allowed to abort if any of five “medical” conditions occur, as outlined in exception 2. These same principles should be applied to female partners when one of them received sperm from a man to become pregnant. However, the sperm donor should have no role in decision making since he would not be an intended, planned, or agreed upon ‘parent.’

Check out Skeptic magazine 27.2 for more articles on the theme of abortion.

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

Conclusions

In this essay I have described a robust right to abortion, which nevertheless should be limited, restricted, and regulated by the state. A female’s right to bodily autonomy and to an abortion can and sometimes does come into conflict with the rights of others, specifically the rights of a fetal person or the rights of the male partner. It is in these circumstances that the state has a duty to intervene and resolve the conflict in a fair and reasonable manner. I have provided rational, ethical, and practical justifications for the right to abortion itself and for the limitations on it. I have designated my view on these matters as the “pro-person position.” It is my hope that the moral rules I have suggested will become commonplace and the laws I have suggested will be adopted at the federal level, and if not there, then at the state level. Only through robust debate may we find common ground. ![]()

About the Author

Gary J. Whittenberger PhD is a free-lance writer and retired psychologist, now living in North Hollywood, California. He was formerly a leader in many freethought groups in Tallahassee, Florida. He received his doctoral degree in clinical psychology from Florida State University after which he worked for 23 years as a psychologist in federal prisons. He has written many published articles on science, philosophy, psychology, and religion.

References

- Glenza, Jessica. “The supreme court just overturned Roe v Wade—what happens next?” The Guardian. 24 June 2022. Web. 2 July 2022. https://bit.ly/3XpCUEt

- Editors. “Planned Parenthood v. Casey.” History.com. 24 June 2022. https://bit.ly/3ZMEx0A

- Gill, Danielle D’Souza. “Anti-Abortion: The Case for Life.” Skeptic. Vol. 27, No. 2, 2022, 18-27.

- Starr, Michelle. “New Research Shows Most Human Pregnancies End in Miscarriage.” Science Alert. 1 August 2018. https://bit.ly/3XncH9F

- “Miscarriage.” Wikipedia. Web. 7 July 2022. https://bit.ly/3ZMITox

- Gelhoren, Giovana. “President Biden Calls on Congress to End Filibuster and Codify Roe v. Wade Into Law.” MSN. 30 June 2022. https://bit.ly/3D0KLAp

- Gupta, Alisha Haridasani. “Why Ruth Bader Ginsburg Wasn’t All That Fond of Roe v. Wade.” New York Times. 21 September 2020. https://nyti.ms/3Wi4ulK

- Whittenberger, Gary. “Personhood and Abortion Rights: How Science Might Inform this Contentious Issue.” Skeptic. Vol. 23, No. 4, 2018, 34-39. https://bit.ly/2JrHPCq

- Watts, Jay. The Problem with Improving Abortion. Christian Research Journal. Vol.45, Number 01, June 2022, 44-48.

This article was published on February 3, 2023.

This is a response both to this article and a previous, companion article published by the same author: “Personhood & Abortion Rights: How Science Might Inform this Contentious Issue.”

It seems clear that Gary Whittenberger accepts as fact that human life begins at conception, as he repeatedly refers to the developing “organism” as “human.” In justifying abortion during the first stages of development, however, he carves out a separate category of “human” and argues that abortion should be restricted to the “human organism” only once it becomes a “person.” He calls that his “pro-person position.”

Despite how reasonable his “pro-person position” may sound, the use of terms “person” and “non-person,” in this and many other contexts, as distinct from simply “human being,” to cover both, has a questionable and, not infrequently, dark history. Closest to Mr. Whittenberger’s argument are those that arose within the Eugenics Movement in the early 20th century, in which the terms were used to justify the forced sterilization of some 60,000 “non-persons” in the U.S.; 3,000 in a single Province in Canada.

Giving Mr. Whittenberger the benefit of the doubt and assuming that his “pro-person position” is done in good faith does not take away from the questionable history of attempts to carve out one kind of human from another. Understanding that history should prove a clear caution to adopting such a distinction as a way to justify any kind of outrage on those deemed to be “non-persons.”

Mr. Whittenberger’s evidence for what constitutes a “person” is based on two things: first, on a developing organism having the “capacity for consciousness”:

“Since the brain is the organ that distinguishes humans from other animal species, it is absolutely essential that “human person” be defined by some emergent feature of the brain. Consciousness is the key feature, since other cognitive abilities and traits either depend on consciousness or are closely related to it. When the fetus becomes conscious for the first time, it then learns something for the first time, namely, what it’s like to be a human organism.”

Second, Mr. Whittenberger argues that results from the scientific literature make it possible to identify when the “human organism” acquires the “capacity for consciousness.” He even appears to claim, as in the quote above, not only that a fetus acquires the capacity for consciousness but also that it actually becomes conscious at some stage in its development. Some might consider that a radical idea. To support his claim regarding “the capacity for consciousness,” he draws on results primarily from neuroscience, which purportedly demonstrate that certain brain structures must be present in the developing fetus to have such a capacity.

Neither of those two things, however, are sufficient to the task Mr. Whittenberger has set for himself: to justify calling a human, early in its development, a “non-person” and a few weeks later, a “person.” Since no one has ever been able to adequately define “consciousness,” the attempt to define a “capacity for consciousness” becomes a hopeless tangle. Even though some neuroscientists talk about their research in such terms, as if they somehow know what it means to have a capacity for consciousness, it remains a fool’s errand when one has no clear, scientific idea what being “conscious” actually means. All they observe are developing structures and activities in the brain, not a capacity for the historically illusive state of consciousness.

There are behavioral indicators that might be used in the service of such a task but those are defined, almost exclusively, for humans after birth and, even then, not until they have acquired language. In fact, it has been claimed that it is not until people have the ability to self-describe that they are actually conscious.” From that point of view, it can be argued that the acquisition of language is what provides humans with a “capacity for consciousness.”

Using such an indicator would mean, however, that “human organisms” do not become “persons,” by Mr. Whittenberger’s reckoning, until they have acquired a language of self-description. Of course, he would hardly agree to “aborting” “human organisms” by that definition, up to the point when they have acquired language, that is, sometime between the first and second year after birth–clearly a ridiculous notion.

The “person” vs. “non-person” argument has been used in many contexts other than trying to offer rational reasons for abortion. In applied eugenics, as mentioned, it justified sexual sterilization to avoid a society with “mental defectives”; in various dictatorships it was used to rid society of “the racially impure non-person” through imprisonment, torture and murder; in both democracies and dictatorships it was used to justify slavery—certain human beings were not persons, they were property; for the Romans, to truly be a person, one had to have a “persona,” that is, “a face before the law”; and, in many religious contexts, “believers” vs. “non-believers” were too often synonyms for “persons” vs. “non-persons,” as a way of justifying extreme forms of outrage on the latter.

Mr. Whittenberger makes his distinction for the purpose of justifying the ending of a human life, an outrage upon those who cannot object. With an inability to define the forever-illusive concept of “consciousness” and, similarly, “capacity for consciousness,” is such a justification just one more variation in a long line of rationales for injustice?

EJ1: This is a GREAT article!

GW1: Eric, thank you for that nice compliment.

EJ1: My only wish is that you would have addressed the scientific and biological reasons for the 24th week cut-off. This is ALWAYS a sticking point when I argue with pro-lifers about this issue.

GW1: I covered that issue in my 2018 article. Here is the link to it:

https://www.skeptic.com/reading_room/how-science-might-inform-personhood-abortion-rights/

EJ1: I usually point out that the two hemispheres of the brain don’t even connect until around the 22nd week or so. Also, we allow families to ‘pull the plug’ on a relative in the hospital that is brain dead – this would just be the same thing in reverse. Finally, pro-lifers use vague terminology like ‘there is brain ACTIVITY in the 5th week’ or some other such nonsense. Hell, there is ACTIVITY everywhere in the embryo during all weeks – but that doesn’t denote a sentient conscious human being!

GW1: All excellent points! We agree.

EJ1: Anyway, great job on the logic and thought processes of this article.

GW1: Eric, thanks for reading it and making your comments.

This is a GREAT article! My only wish is that you would have addressed the scientific and biological reasons for the 24th week cut-off. This is ALWAYS a sticking point when I argue with pro-lifers about this issue. I usually point out that the two hemispheres of the brain don’t even connect until around the 22nd week or so. Also, we allow families to ‘pull the plug’ on a relative in the hospital that is brain dead – this would just be the same thing in reverse. Finally, pro-lifers use vague terminology like ‘there is brain ACTIVITY in the 5th week’ or some other such nonsense. Hell, there is ACTIVITY everywhere in the embryo during all weeks – but that doesn’t denote a sentient conscious human being! Anyway, great job on the logic and thought processes of this article.