“Hoover’s strengths lay not in any great instinct for media manipulation or press management, but in the areas that had always served him well: the ability to learn quickly, to adapt to new situations, and to deliver what he believed his bosses wanted.” (G-Man, 168)

“The Bureau was on the side of law and order, that is, God’s side… Breaking the law was permissible, as long as it was for the greater glory of God.” (Gospel, 58)

Skepticism involves doing the hard work of both acknowledging thought distortions and researching more nuanced explanations based on additional data. Studying the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is, perhaps surprisingly, relevant to skepticism, partly because of the Burueau’s involvement in controversial claims. G-Man offers new evidence about how the FBI skirted the limits of the law in its investigations, and that there was a real conspiracy to cover up any evidence of this in the first days after Hoover died. Given the FBI’s controversial involvement in national politics, both books are well-timed as once-classified documents are released and make headlines.

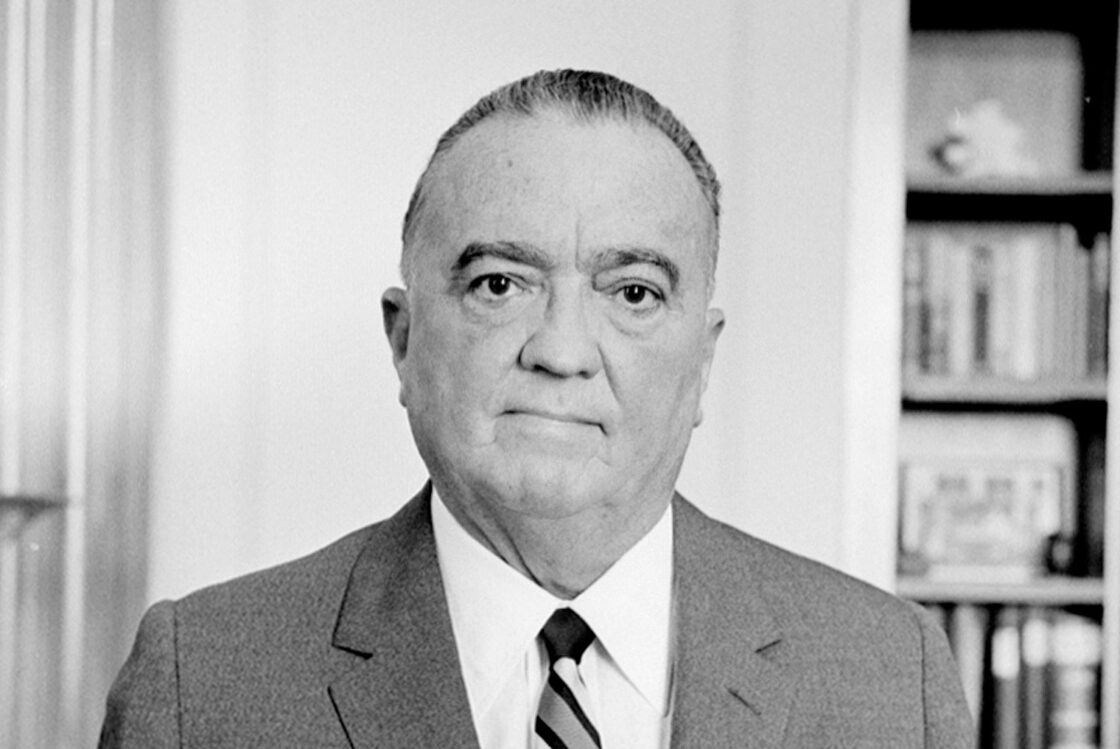

John Edgar Hoover was instrumental in the formation of the FBI as we know it today. The agency was less than a decade old when Hoover was hired in 1917, and he became Director just seven years later at the remarkably young age of 29, a position he held until his death in 1972. The FBI gained its current name (and the ability of agents to carry guns) battling gangsters in the 1930s, which launched Hoover and the Bureau into the headlines. The FBI became even more respected as the country’s defender against espionage. The Bureau’s response to the Civil Rights movement generated some controversy and divided opinion, and Hoover died days before the Watergate Hotel break-in that would ultimately lead to the fiercest criticism of the Bureau since before Hoover’s directorship.

The length of Hoover’s reign is often attributed to “politely delivered” blackmail, but Gage persuasively argues that Hoover’s longevity as Director had more to do with the FBI’s exemption from Civil Service hiring rules for agents, his underappreciated genius as a bureaucrat, and a few strokes of random chance that went in his favor.

Gage, a historian at Yale, uncovered the unredacted version of the anonymous letter that the FBI wrote to Martin Luther King Jr., urging him to commit suicide, truth being stranger than fiction. However, social norms change, and this is part of Gage’s thesis in G-Man: instances of Hoover’s antisemitism, racism, and sexism were, in fact, reflective of the mainstream a century ago; he mirrored most of the society in which he lived. Perhaps not coincidentally, when Hoover went to law school, civil liberties theory barely existed, having been birthed largely out of the events of World War I. Despite finding other evidence as to Hoover’s racism, Gage documents that Hoover opposed the race-based mass internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Although Hoover has been praised for most of his early reforms professionalizing FBI policy and practice, he also fired most Jewish employees and Black agents when he became the Director. When later criticized for having so few African American agents, he inflated their numbers by having his Black chauffeur go through the motions of becoming an agent, though his only assignment remained that of driving the Director. The FBI did not have any Black men working as Special Agents until 1962.

Also part of Gage’s thesis is that Hoover’s FBI was more central to mid-20th century America—and to the rise of conservatism—than has previously been understood. This begins with Hoover’s underappreciated early career role as the underling in charge of the post-World War I Palmer Raids (named for Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer) on American radicals. It continues with Hoover’s Depression-era moralism, his difficulty distinguishing action from speech in spy hunts of World War II and the early Cold War, and culminates with Hoover’s increasingly outspoken views on religion and the Bureau’s interference with the 1960s Civil Rights movement.

G-Man’s narrative of biography and discussion of the FBI is seamlessly interwoven. While this is partly due to Gage’s considerable ability as a writer, the task is made easier because of the unusually high degree of overlap between them. The Bureau was Hoover’s full-time job for his entire adult life, and the author provides new evidence that most of Hoover’s off-hours socializing were spent with other FBI agents, partially in groups he created as Director. Gage even discovered that Hoover’s college fraternity was his preferred source from which to hire, including for FBI leadership positions. During his tenure, the FBI’s responsibilities and staff both exploded, which gave him an outsized influence on the development of bureau culture.

Much of G-Man’s history is based on applying existing scholarship to the study of the FBI, and Gage is masterful in her ability to cover a vast number of topics concisely without slowing the narrative, while also being able to underscore important points without ever seeming repetitive. G-Man is that rare gem of a book that can be enjoyed by the novice while also being appreciated by the scholar.

For example, while Gage makes a strong case that Hoover’s near half-century as FBI Director was due to his skill at both the job and at navigating political bureaucracy, his relationship with President Kennedy may be an exception: although Gage denies that Hoover blackmailed the President into unexpectedly keeping him on as Director, she does provide evidence for the plausibility of blackmail in this case. Ironically, Hoover’s reputation might be better if he had stepped down then: his approach to organized crime conflicted with that of Attorney General Bobby Kennedy, the President’s brother and Hoover’s boss. Although Gage states that Hoover lied to the Warren Commission investigating Kennedy’s assassination, she makes clear that he only did so to save the FBI from embarrassment, and that Hoover strongly believed in Oswald’s guilt as the lone assassin.

One of the secondary sources used by Gage is R. Jeffreys-Jones’s The FBI: A History. It forms a solid complement to Gage’s book, filling in the history of the FBI before and after Hoover. Similarly, Gage’s discussion of Hoover’s sexuality brought to mind D.M. Charles’s book Hoover’s War on Gays. Gage offers new evidence that Hoover was gay, which is relevant, even for an academic historian, for two reasons. First is the probable hypocrisy of the FBI’s “Sex Deviates” program and the FBI’s central role in the anti-gay “Lavender scare” of the early Cold War. More interesting, perhaps, is Gage’s documentation that in the inner circle of the Washington DC social world, his same-sex partnership was more accepted in the 1930s than in the 1950s, and a reminder that historical change is not entirely unidirectional. Hoover’s dual stance on homosexuality illustrates another theme that Gage’s research highlights—Hoover succeeded by adapting when it was necessary to further his career.

Hoover’s imposing his (at least professed) morals on the FBI, which amplified the acceptance of that Manichean view on the whole country, is just one of many themes of G-Man. In contrast, The Gospel According to J. Edgar Hoover places that issue front and center.

Both authors agree that only family circumstances prevented Hoover from choosing the ministry as his career, but his Pastor claimed that he imparted Christian values to the Bureau. Hoover opposed the imposition of Christianity as a state religion, but consistently said, publicly and privately, that “godlessness” was the country’s greatest threat.

As Director, Hoover could enforce these beliefs on the Bureau. In the 1930s, he instituted an annual Catholic spiritual retreat for agents, regardless of their religious belief, which Martin suggests was promoted so heavily in the bureau that it felt mandatory, to the point where lack of attendance could damage an agent’s career. For religious balance, as well as a chance to proselytize to non-agent employees, “The FBI initiated an annual Mass and Communion Breakfast in 1950,” eventually subsidizing it so that lower-salaried employees could not use its cost as an excuse not to attend. Martin supports all of this with primary source documents and first-person interviews. Black FBI agents were prohibited from attending the annual Catholic spiritual retreat. When the annual prayer breakfast and mass were so successful that agents organized a more frequent semi-official group attendance at a Protestant Vesper service, the church chosen was said to be the most racist one in the region.

From 1960 until his death, Hoover wrote essays for the magazine Christianity Today, which were so popular that, in one year, requests for reprints exceeded the circulation of the magazine. They were available, at taxpayers’ expense, from the FBI.

Hoover may have overstepped when, upon being enraged by the new Revised Standard Version of the Bible, he ordered the FBI to open an official investigation of it in January 1953. All of Hoover’s pro-Christian work did not go unnoticed among the religious. Although Presbyterian, many Americans believed he was Catholic, since he publicly praised that denomination and spoke before Catholic groups so frequently. He was publicly lauded by Christian organizations of many types, including The Chicago Bible Society, the National Religious Broadcasters, the Jesuits, the Pentecostals, and the Billy Graham Evangelical Association.

Unlike Gage, Martin extends his analysis beyond Hoover’s death, noting that as of 2021, only four percent of Bureau agents were Black, despite repeated lawsuits. He mentions that a woman who was the FBI’s Personnel Director in the early 2000s believed that evangelicals were the best group from which to hire. More recently, the FBI has been criticized for monitoring Muslim or Black extremists far more closely than racist White extremists.

At the least, the FBI has had a history of discriminating against any would-be employee who is not a conservative White Christian man, with conformity necessary for acceptance within the Bureau. Potentially more dangerous is the message, often implied and sometimes stated outright, that when laws and conservative Christian values are in conflict, conservative Christian morals must prevail.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 28.3

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

Both books have minor faults. When Gage cites books solely by author, it is important that they be listed in the bibliography. The one by Jeffrey Stone isn’t. I was expecting more historical context in Martin’s Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover, which is closer to being a monograph than a narrative, and what context he does give is more theological than historical. Martin does not provide a significant discussion of White Christian conservatism outside of the FBI, which I view as a missed opportunity.

Gage’s book places the FBI as a shaper as much as a reflector of U.S. values. Martin underscores that for the FBI, the value of law and order is seen as embedded in a dangerous overlap of racism and a Christian belief in the goodness of God. Gage documents in greater detail than Martin how Hoover absorbed these values as a youth, while Martin details more than Gage how he infused these values into the FBI strongly enough that they survived until today, 50 years after his death. The two books complement each other well, and I highly recommend both. ![]()

About the Author

Michelle Ainsworth holds an MA in History and she is currently researching the cultural history of stage magic in the United States. She is a humanist and lives in New York City.

This article was published on November 29, 2023.