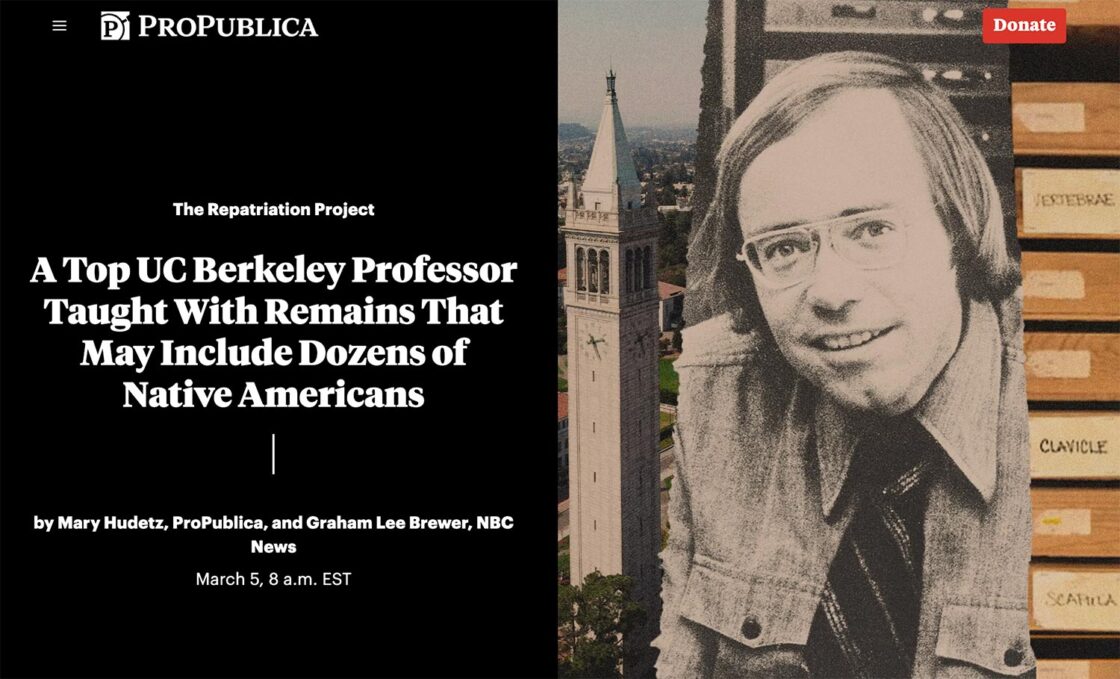

On March 5, 2023, NBC News, in conjunction with ProPublica,1 a nonprofit newsroom that investigates “abuses of power,” published what can only be described as a hit piece against the legendary paleoanthropologist Tim White, now a professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley. Other news outlets, such as the SFGATE and AOL, picked up the story.2, 3 The article revolved around Tim White’s use of a skeletal teaching collection that may contain Native American bones and teeth.

UC Berkeley has recently faced criticism for having Native American bone collections and, thus, they have changed their policies to ramp up repatriation efforts, abandoning their long-held view that teaching and research should be prioritized. Repatriation involves turning over bone and other artifacts to a Native American tribe that claims an ancestral connection to them.

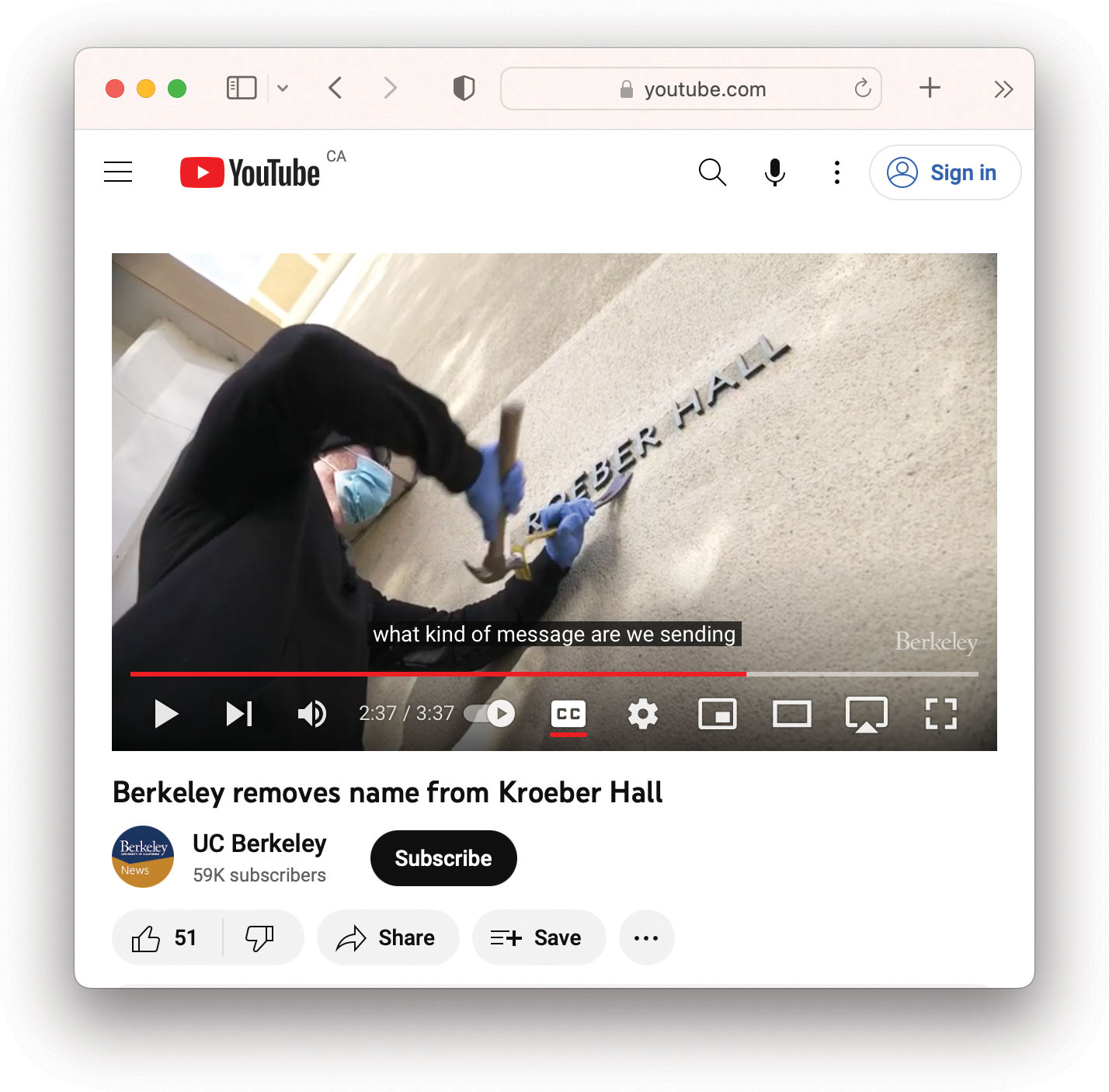

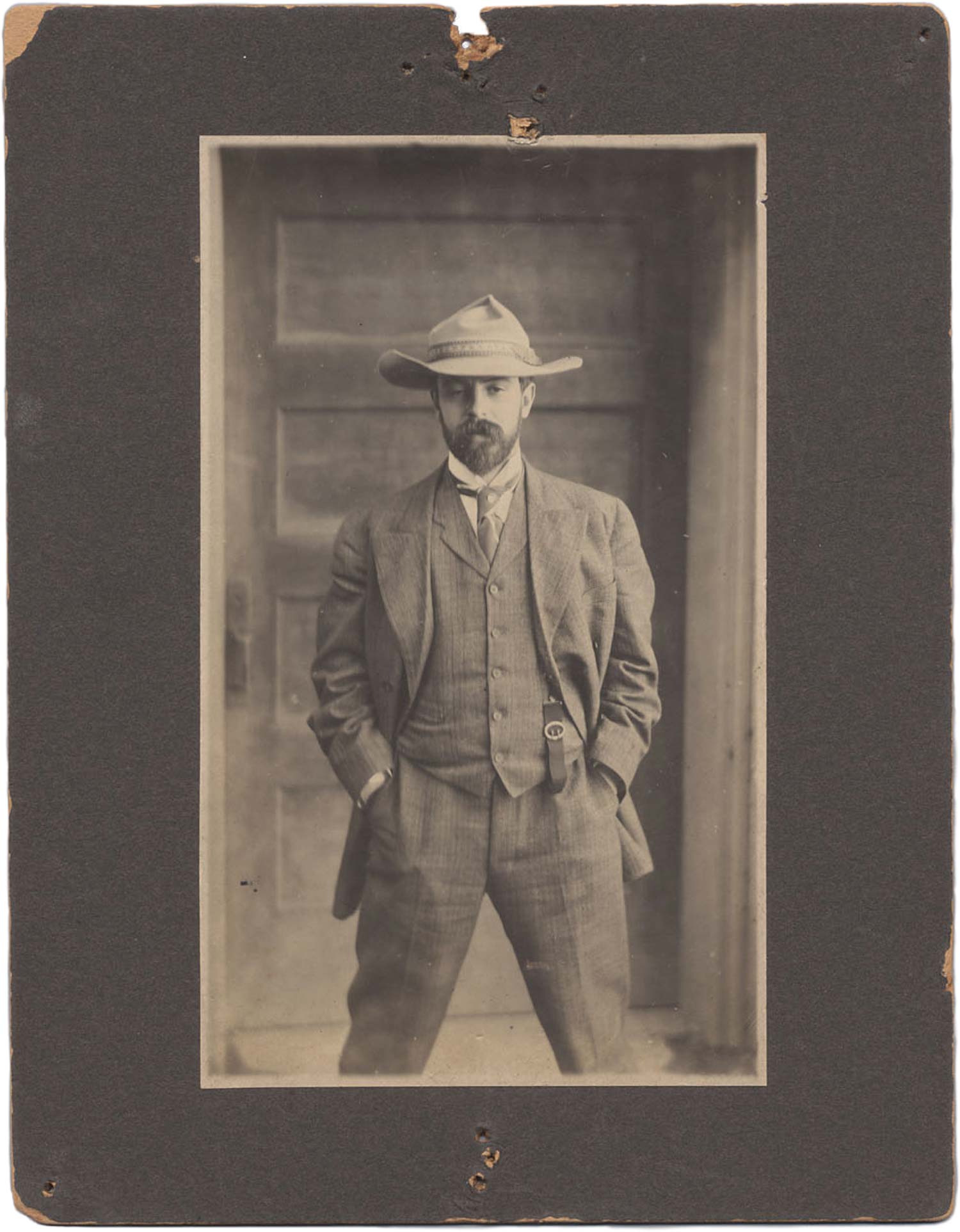

Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) and similar state laws were intended to unite human remains, sacred objects, associated funerary objects, and items of cultural patrimony with their lineal descendants and culturally affiliated tribes. Teaching collections, which are of unknown origin and have been used to train the next generation of osteologists— from forensic anthropologists to orthopedic doctors—were not intended to be included in these laws. Yet, repatriation activists are attempting to claim these collections, and they are also attacking those who have used the collections. University administrators, including anthropologists working to repatriate remains, are helping this latest phase in the repatriation compromise. Repatriation activists have already successfully campaigned to remove the name of the first anthropology professor at UC Berkley, Alfred Kroeber, from the anthropology building.4 Tribes have also successfully claimed artifacts that have no affiliation to Native Americans, such as a 16th century Spanish breastplate.5

Alfred Kroeber was the first professor of anthropology at UC Berkley. In 2021, the university removed his name from the anthropology building. (Credit: Screenshot of UC Berkeley video by Roxanne Makasdjian and Clare Major)

Let us now return to Tim White. As one of the world’s most influential paleoanthropologists, he shaped the field on multiple levels. He discovered two species of over 4-million-yearold early human ancestors from Ethiopia: Ardipithecus kadabba and Ardipithecus ramidus. These two species are close to the base of the human evolutionary family tree. They are the best contenders for the first early humans, over a million years older than Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis. White is also the author of the best-selling textbook, Human Osteology,6 a beautifully illustrated work that helps guide students in learning bone anatomy and contains fascinating case studies of forensics, human evolution, and archaeology. White revived research on cannibalism, and in 1992 put forth a rigorous method to ensure that sites where cannibalism was indeed practiced, are correctly assessed.7

Alfred Louis Kroeber, regarded as the founder of the study of anthropology in the American West, shown here circa 1907. In 1901, he began his more than 40-year career at UC Berkeley’s Department of Anthropology, and was Director of the university’s anthropology museum from 1909 to 1947. (PIC 1978.128 courtesy of UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library)

Because he understands how valuable bones are in telling us about the past, White has also been conscientious in following repatriation laws, such as NAGPRA.8 He played a key role in the repatriation debate, rightly arguing that repatriation of remains needs to be made on a preponderance of evidence, scientific and otherwise, that shows an affiliation between the human remains and the modern-day tribal claimants. In one case, White, along with Robert Bettinger of UC Davis and Margaret Schoeninger of UC San Diego, sued the University of California for access to study 9,000-year-old Paleo-Indian remains found on the campus which could help us understand the First Americans. The researchers lost the lawsuit on the grounds that the tribes claiming the remains (who were not parties to the suit) would have to be made parties to the suit to adjudicate adequately the claims of the plaintiff-anthropologists, and that therefore the plaintiffs’ suit would be dismissed.9 The remains were transferred to the La Posta Band of Digueño Mission Indians based on a geographic link coupled with oral creation myths. At UC Berkeley, White was, for many years, part of the university’s repatriation committee in which he served in an advisory role (professors don’t make repatriation decisions; chancellors do) and strictly adhered to the law, which calls for a balancing of scientific proof along with other evidence.

Tim White started teaching at UC Berkeley in 1977; for decades, he has taught osteology to thousands of students. Human osteology is learned by anthropology students who plan to go into human evolution research, archaeology, and forensics, but it is also a class for future orthopedic doctors. These students were taught to identify human remains, understand bone biology, and determine basics such as the sex of the remains. There is no way to teach someone osteology correctly without using a skeletal collection as reference.

Teaching collections are distinct from research collections, which have information of provenience (origin), and documents regarding excavation history, and can be assessed for details including antiquity, number of individuals, culture, and much more. Research collections ought not to be used for teaching (so that research collections stay intact), and one of the first changes that I (EW) made when I got to San José State University was to properly separate teaching and research collections, including ensuring that others followed the new stricter guidelines.

Teaching collections are in place to teach, but they also help the maintenance of research collections by allowing osteology to be taught with remains that are of unknown provenience. As I (EW) explain to my students, the “UK” marks on the bones in our teaching collection do not stand for “United Kingdom” but for “unknown.” In other words, they cannot be affiliated with any tribe.

In the ProPublica/NBC article, Tim White was accused of poor storage of human remains because there were drawers of bones that were sorted by bone, e.g., a drawer of femora (thigh bones) or a drawer of humeri (upper arm bones). This is an appropriate storage method for teaching collections; every university that I (EW) have visited—from the U.S. to Canada and across the Atlantic in Europe down to Kenya in Africa—uses a similar sorting method for their teaching collections. Accusing White of mishandling remains for this practice is absurd; further absurdity ensued when the authors attempted to paint this as some house of horrors that evokes an evil professor standing over his past victims.

In addition, the university and the journalists acted as if White had hidden this collection from repatriation efforts. But there was no clandestine action at all on White’s part. He followed both the legal requirements of NAGPRA and the university policy. NAGPRA requires federally funded institutions, such as universities, to repatriate human remains when they can be affiliated to an existing tribe. The law was designed to be a compromise. It allows for the continuation of research on unaffiliated collections as well as the continuation of maintaining teaching collections. It is not a law about reburying Native American skeletal remains; it is intended to repatriate ancestral bones to culturally affiliated tribes.

Thus, the collection White used to teach classes from 1977 to 2018 was never subject to NAGPRA, as the remains are of unknown origins and cannot be affiliated to any specific tribes. Indeed, the remains may not even be Native American! As Tim White explained about teaching collections: “There’s nobody on this planet who can sit down and tell you what the cultural affiliation of this lower jaw is, or that lower jaw is. Nobody can do that.” The articles criticizing White do not dispute that assertion or provide any basis for disputing it. Furthermore, the UC Policy10 that was in effect from 1985 through 2020, and only changed in 2021,11 stated that:

…the University’s collections of human remains and Cultural Items serve valuable educational and research purposes important to the enhancement of knowledge in various disciplines. The University maintains these collections as a public trust and is responsible for preserving them according to the highest standards while fulfilling its mission to provide education and understanding about the past and present through continued teaching, research, and public service.

Further, regarding teaching collections, the policy statement included the following:

Given the importance of the study of human osteology in archaeology, paleontology, and comparative morphology, and the importance of skeletal material in training students at the lower division, upper division, and graduate level, campuses normally retain the discretion to use such items in teaching. Campuses are encouraged to take into consideration the views and concerns of Native American and Native Hawaiian representatives when making decisions regarding the teaching and research use of Native American and Native Hawaiian skeletal materials.

This policy even allowed for culturally affiliated collections to be maintained and utilized, but left the decision up to the tribe rather than the university:

In circumstances in which cultural affiliation (or cultural association) has been established or other repatriation requirements have been met but in which an affiliated (or associated) tribe has chosen not to request repatriation, an affiliated (or associated) tribe may request that the affiliated (or associated) remains or Cultural Items not be used for teaching or research. The decision of the affiliated (or associated) tribe as to whether the remains and cultural items can be used in teaching or research shall normally be accepted as final by the University, subject to exceptions provided by federal law.

These policy statements were written in anticipation of NAGPRA’s passing. The policy, which balanced Native American concerns with those of the university’s education and research mission, was replaced by a policy that abandoned this balance and called for a cessation of research and teaching on all collections until it can be determined they do not fall under NAGPRA, or California’s equivalent CalNAGPRA.12

In 2019, the University of California’s president called for reporting of all skeletal collections on all ten campuses, which went beyond simply looking at anthropology department research collections. It was at this point that White notified Hearst Museum Director Lauren Kroiz and NAGPRA Liaison Tom Torma of the teaching collection. Thus, all along the way, White scrupulously followed the rules of the University of California and never broke state or federal repatriation laws.

The teaching collection White used was created before his arrival; it is over a century old. Teaching collections usually contain remains from a variety of sources. At San José State University where I (EW) teach, the teaching collection predates not only my arrival but also that of my predecessor; it contains remains from medical donations, remains likely purchased from India when it had a thriving skeletal trade, and remains likely from historical and archaeological sites. The collection at UC Berkeley, from descriptions found in letters to the Native American Heritage Commission13 (the nine-member body administering the California Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) written by Dr. Sabrina Agarwal, the University’s Chair of the NAGPRA Advisory Committee, seems similar to the collection at San José State University and to many teaching collections around the globe.

Repatriation of remains needs to be made on a preponderance of evidence, scientific and otherwise, that shows an affiliation between the human remains and the modern-day tribal claimants.

Upon examination of the collection Sabrina Agarwal noted that 22 individuals were not Native American; these likely came from medical donations, as determined by writing on the bones. However, she also stated that there was a minimum of 95 individuals who could be Native American.14 It is difficult to fathom how she came to this conclusion. Minimum number of individuals (MNI) is a technique used to determine the minimum possible number of individuals from a site of commingled burials; it cannot be used for a collection that has been built from an accretion of materials over decades and which contains many fragments. For instance, in a site where there are 15 left femora and 9 right femora, the assumption is that if you can match 9 of the left femora with the right femora, then the MNI is 15.

However, if you had the same number of femora and some were of an unknown side, you may get a very different MNI—for instance, with 7 left femora, 9 right femora, and 8 un-sided femora, the MNI is 12. The 7 left femora and two of the un-sided femora can be paired with the 9 right femora, the remaining 6 un-sided femora could be paired to give three more individuals; thus, the number is 12. There are other methods that use landmarks, require that each bone be at least 50 percent complete, or look at zones of bones rather than sides. Regardless of the specific method used, the techniques further take into account bone size and the individual’s estimated age at death. Considering that the teaching collection was described by Agarwal as represented by “thousands of smaller disarticulated and commingled skeletal and dental remains,” there is no way to determine MNI in such a collection.

Another issue is that Agarwal wrote in her letter to the Native American Heritage Commission that “no in-depth or destructive analysis was made”; yet, she could somehow detect that the majority of the teaching collection could have come from Native American remains. How could this be determined? Even with close examination and in-depth analysis of the remains, determining ancestry requires nearly complete skulls or DNA. Even if she is correct in her assumptions, this still leaves the fact that repatriation laws are not acts to rebury Native American bones; they are to repatriate remains to affiliated tribes. I (EW) reached out to Agarwal asking how she concluded that there was a minimum of 95 individuals and how she concluded that these remains were Native American; no reply was received.

It is likely that UC Berkeley’s teaching collection will be lost, and tribal repatriation activists will bury the remains, even if they are not Native American. This will open the door for more losses of teaching collections. Once research collections are slated for repatriation, tribal activists will come for teaching collections believed to be Native American; then they will come for all human bones. And it’s worse than that—I (EW) have been told that even images of skeletal remains (Native American or not) may cause “harm” to tribal members. Even X-rays are already a target, as we have written about in the journal Regulation.15

Such procedures that harm science in general and anthropology and archaeology in particular won’t end there. In the ProPublica/NBC article we mention in the opening paragraph, the cultural director of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, lamented that, “The university housed recordings and items that ethnographers and anthropologists had previously collected from Chumash elders.” And, she said: “They stole those items.” Don’t be surprised if they come for ethnographic materials next.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 28.3

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

The scandal-promoting news reports, with their expressions of anguish, anger, horror, and shame, accompanied by accusations of desecration, stealing, looting, lying and grave robbing, ignore the question of why Tim White, or anyone else, would legitimately want to study bones. The answer is that they provide unique information and insight—not available from any other source—into human history and prehistory. These include disease, injury, occupational activities, diet, DNA relationships, the presence of certain alleles with known adaptive value, the age and sex structure of the population, population size and density, and cultural practices associated with disposition of the dead. In Europe and Asia, where such research is not suppressed, scientists are making huge strides in pursuing such inquiries.

The same scandal-promoting reports ignore the complexity of NAGPRA, which requires evidence of cultural affiliation for repatriation to occur. In many cases, repatriation activists offer as evidence oral traditions that have no temporal or geographical grounding, but rather consist of tales of supernatural creatures and events that would not be accepted as evidence if offered by any other racial group in the United States.

If public schools cannot teach Biblical creationism (as courts have so ruled, including the United States Supreme Court in the Louisiana creationism case), it is difficult to see why Native American animist creationism should be accepted as proof in American legal proceedings. ![]()

About the Author

Elizabeth Weiss, professor of anthropology at San José State University, has spent over two decades studying skeletal remains to try to understand past peoples’ lives. Weiss has written over 100 articles in journals ranging from the American Journal of Physical Anthropology to Quillette. You can find more of her work at: elizabethweiss74.wordpress.com.

James W. Springer is a retired attorney and anthropologist based in Peoria, Illinois. He is the co-author, with Elizabeth Weiss, of the book Repatriation and Erasing the Past (University of Florida Press, 2020), which takes a critical look at laws that mandate the return of human remains from museums and laboratories to ancestral burial grounds.

References

- https://bit.ly/40fTPuu

- https://bit.ly/40cVam7

- https://aol.it/3K3agEV

- https://cnn.it/3lzyM7n

- https://bit.ly/3TJU6mZ

- White, T. D., Black, M. T., and Folkens, P. A. (2011). Human Osteology: Third Edition. Academic Press.

- White, T. D. (1992). Prehistoric Cannibalism at Mancos 5MTUMR-2346. Princeton University Press.

- https://bit.ly/3JJ2rD8

- White v. University of California, 2012 WL 12335354 (N.D. Cal. 2012), aff’d, 765 F.3d 1010 (9th Cir. 2014), cert. denied 136 S. CT. 983 (2016)

- https://bit.ly/3LQbrc5

- https://bit.ly/3K9cfrv

- https://nahc.ca.gov/calnagpra/

- https://nahc.ca.gov/

- https://bit.ly/42RHcb5

- https://bit.ly/3FLzbdt

This article was published on November 22, 2023.