“A great part of my life’s work has been spent to destroy my own illusions and those of humankind.”

“What a distressing contrast there is between the radiant intelligence of the child and the feeble mentality of the average adult.”

Over the past half century, some of Sigmund Freud’s ideas have been debunked, and he personally has been exposed as a doctor who misunderstood and harmed a good number of his patients.1 I do not take exception to this evaluation. Especially during the years when he was building his career as a doctor, the founder of psychoanalysis deceived the public, if not himself, about the evidence for his views and his ability to cure. There is, however, another side to Freud’s character and to his achievements that the critics overlook. Indeed I believe that Freud belongs up there in the pantheon of great skeptical humanists alongside Socrates, Voltaire, and Hume. Like them, Freud believed that reason could help people undo the hypocrisies and deceptions in their lives, permitting a recovery of sanity and a measure of happiness.2

As well, Freud’s critics fail to recognize the contributions made over the past century by the psychoanalytic movement that he inaugurated. To make this second point, I’ll review the accomplishments of Sigmund Freud’s daughter Anna, whose role was pivotal in developing psychoanalysis in an open-minded, evidence-based way. Her work is a telling counterexample to the broad claim that psychoanalysis is an irrational theory and ineffective practice.3 Anna Freud and her colleagues not only observed assiduously, but also subjected the very concept of “observation” to scrutiny. When adults are observing and interacting with children, Anna Freud recognized, their perceptions may be clouded by their prior expectations: observers see what they wish to see and overlook or push aside everything else.

Mistaking Our Own Motives

Although Sigmund Freud’s own professional conduct was marred by the prejudices of his time, some of his concepts do cast light on the sources and nature of human irrationality. Freud believed that the mind is influenced by unacknowledged motives and unspoken memories. And that belief informed not only his “talking cure” therapy but also his social activism on behalf of issues that ranged from free mental health care to the humane treatment of shell-shocked soldiers who had survived the First World War.

Since the early 17th century when Rene Descartes penned his Meditations, rationalist philosophy had held that the human mind is unified and transparent to itself. Freud affirmed instead—and this is the premise that still informs psychoanalysis today—that humans are inclined, by nature and by nurture, to mistake their reasons for believing and acting. That we are fallible in this manner, mentally conflicted and influenced in ways that we only partly understand, is a condition that Freud found illustrated ubiquitously in dreams, slips of the tongue, religious beliefs, sexual preferences, and the foibles of our relationships with others. And he made this “diagnosis” of the human condition the basis for doing psychotherapy in a new way.

Freud perceived himself as following in the footsteps of those who had in the past challenged the pretense that human beings stand exalted as masters of their own fate and the pinnacle of creation:

Humanity has in the course of time had to endure from the hands of science two great outrages upon its naive self-love. The first [ascribed to Copernicus] was when it realized that our earth was not the center of the universe, but only a tiny speck in a world-system of a magnitude hardly conceivable…. The second [ascribed to Charles Darwin] was when biological research robbed man of his peculiar privilege of having been specially created, and relegated him to a descent from the animal world, implying an ineradicable animal nature in him.

Human pride now has to suffer, Freud wrote, a third, “most bitter blow” from empirical inquiry, which discloses “to the ‘ego’ of each one of us that he is not even master in his own house.” This view of the mind’s internal division launched what might be called a “research program” that since the turn of the 20th century has encompassed a great deal of qualitative and quantitative study of human psychology. And much of that study has been skeptical in character, calling into question not only conventional understandings of individual pathology but also wider cultural values and practices.

Psychoanalysis as a Research Program

It’s true that not many studies conducted within a psychoanalytic framework satisfy the gold standard in medical science: the randomized controlled trial based on quantification and statistical analysis. Certainly the activity of observing a child in a clinic is quite different from that of observing a planet through a telescope or a bacterium on a petri dish. But these forms of inquiry have much in common as well. The qualitative research carried out in Anna Freud’s “laboratories”—nurseries, clinics, residential and day care centers—was guided by the same criteria of systematic observation, conceptual parsimony, and explanatory power that guide rational empirical inquiry of any kind.

At the core of the psychoanalytic research program stand not only theoretical propositions but also an ethical principle—a commitment to humane care for people suffering intense psychological distress. Against the centuries-old stigmatization of mentally disturbed people as “mad,” Freud and his followers advocated tolerance and compassion. To be sure, the psychoanalytic profession has not always lived up to these values. In some parts of the world, including the United States, during the 20th century psychoanalysis became an enterprise governed by a medical elite that was self-serving and dogmatic. And psychoanalysts, beginning with Freud himself, indulged in a great deal of unwarranted and harmful speculation: pathologizing homosexuality4, attributing women’s wishes for independence and equality to “penis envy,” positing metaphysical entities like “the death drive,” etc. When Freudianism became an entire “climate of opinion,” as Auden described it at mid-century, that climate was not universally a liberating one. On the other hand, psychoanalysis did give support to progressive movements during the 20th century that ranged from the Harlem Renaissance and civil rights struggles in the South to gay liberation and the women’s movement.5 Feminists such as Juliet Mitchell, Nancy Chodorow, and Jessica Benjamin rejected the assumptions made by mainstream psychoanalysis about women’s and men’s “normal” roles and behaviors; yet they found psychoanalytic concepts useful for understanding the childhood origins of gender differences and the devaluation of women’s lives. Perhaps psychoanalysis’ most consequential contribution, though, has turned out to be its reconsideration of the norms for raising children. The science of this subject was advanced by researchers such as Anna Freud, Margaret Mahler, D.W. Winnicott, John Bowlby, Mary Ainsworth, Selma Fraiberg, and Daniel Stern. These studies influenced Spock, Leach, Brazelton, and other authors of widely read books that give families advice about relating to children.

Another domain impacted by psychoanalysis was jurisprudence: conventional legal assumptions about human free will, responsibility, and punishment were challenged, often successfully, by considerations that pointed to the sometimes exonerating psychological and social origins of criminality. Eminent judges including Holmes, Frankfurter, Cardozo, and Frank even reflected on the possibility of unconscious prejudices entering into their own deliberations.6

In brief, as a research program interacting with medical, educational, legal, and other cultural institutions, psychoanalysis has made many important contributions.

Sigmund Freud’s Critique of Religion: “The Future of an Illusion”

Sigmund Freud began psychoanalysis by inquiring into individual pathology but later in his life sought to understand civilization’s “discontents” as well. Freud believed that religion is one of the domains in which human reason runs aground. In his 1927 essay, “The Future of an Illusion,” Freud not only exposes the irrationality of belief in God (others before him had done that) but he goes a step further and aims to explain that irrationality. Responding to their experiences of helplessness, Freud suggests, humans seek a benevolent, all-powerful protector who will shelter them from suffering and uncertainty and assure an orderly world. God, as conceived in most biblical traditions, is modeled after an adult authority who towers over a child, promising guidance and reward, but also severe punishment for misbehavior.7

In keeping with Daniel Dennett’s discussion later in the 20th century of the “intentional stance,”8 Freud points out that people imbue nature with subjective agency:

Impersonal forces and destinies cannot be approached; they remain eternally remote. But if the elements have passions that rage as they do in our own souls, if death itself is not something spontaneous but the violent act of an evil Will, if everywhere in nature there are Beings around us of a kind that we know in our own society, then we…are still defenceless, perhaps, but we are no longer helplessly paralyzed; we can at least react…. we can try to entreat them [supernatural beings], to appease them, to bribe them, and, by so influencing them, we may rob them of a part of their power.

In the course of the evolution of the human species as well as in the personal history of each individual, Freud argued, there occurs a kind of thinking that creates imaginary beings and narratives, dispensing with the empirical constraints that govern our everyday practical interactions with our surroundings. Religion in its traditional patriarchal forms exemplifies such thinking when it authors a story such as the one told in the Bible, Koran, or other canonical text, a story that serves the purpose of representing a well-ordered and protective world. Beginning with Freud, psychoanalysis finds a similarity between such religious stories and children’s “make-believe”—that wonderful expression in English that conflates imagining with believing. Notoriously, the inconsistencies of these narratives with everyday facts does not make them less real. A child whose imagined companion is a blue creature with five legs needn’t be fazed by an adult who points out that all animals encountered in the past have, at most, four legs. “My friend has five, I can count them!” Everything is possible for a creative imagination free of constraints imposed by reality. And for that reason, religion, which Freud believes is developmentally as well as conceptually continuous with children’s magical thinking, does not respond to evidence-based objections. “Primary process,” the name that Freud gives to thinking of this kind, is associative and metaphorical: “There are in this system no negation, no doubt, no [mere] degrees of certainty.” “Secondary process,” on the other hand, is cognition that weighs evidence and recognizes a difference between appearance and reality, and that is willing to sacrifice fantasy’s immediate gratification in favor of long-term real gains.

This distinction between two ways of thinking about the world is widely recognized today. Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow, for instance, posits a neurological difference between two kinds of cognition—“System 1” is fast, instinctive, and emotional, while “System 2” is slower, more patient and logical—that is remarkably similar to Freud’s distinction elaborated a century ago. Freud’s critique of religion anticipates as well the reasoning that would be advanced later in the century by skeptics like Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and Michael Shermer. For instance, in response to the tu-quoque argument—“Sure, religion rests upon ultimately unjustified basic premises and arrives sometimes at mistaken conclusions, but doesn’t science too?”—Freud writes:

You will not find me inaccessible to your criticism. I know how difficult it is to avoid illusions; perhaps the hopes I have confessed to are of an illusory nature, too. But I hold fast to one distinction. Apart from the fact that no penalty is imposed for not sharing them, my illusions are not, like religious ones, incapable of correction…. If experience should show…that we have been mistaken, we will give up our expectations.

Freud points out that unlike religion, science evolves in relation to its empirical encounter with reality:

People complain of the unreliability of science how she announces as a law today what the next generation recognizes as an error and replaces by a new law whose accepted validity lasts no longer. But this is unjust and in part untrue…. A law which was held at first to be universally valid proves to be a special case of a more comprehensive uniformity…. a rough approximation to the truth is replaced by a more carefully adapted one, which in turn awaits further perfecting. There are various fields where we…test hypotheses that soon have to be rejected as inadequate; but in other fields we already possess an assured and almost unalterable core of knowledge.

Freud eloquently articulates here a robust empiricism. Of course science is, as Freud recognizes, imaginative too, but, in the words of another Austrian, Karl Popper, scientific “conjecture” is subject to “refutation.” (Freud often failed to “practice what he preached,” however; he notoriously dismissed objections to his own views as psychological “resistance.”)

Freud was aware that rational considerations are unlikely to successfully challenge the grip of religion on believers: “motives based purely on reason have little effect against passionate impulses.” Those impulses, Freud submits, receive cultural encouragement that typically begins with the religious instruction of children:

Think of the depressing contrast between the radiant intelligence of a healthy child and the feeble intellectual powers of the average adult. Can we be quite certain that it is not precisely religious education which bears a large share of the blame for this relative atrophy?

The connection made here between religion and childhood “atrophy” was, not surprisingly, poorly received by civil and political authority in the country Freud was living in. Invested in the preservation of traditional “family values” and staunchly opposed to liberal reforms in education and mental health services stood the Roman Catholic Church, a bastion of reaction in Austria, Italy and elsewhere in Europe. In the 1920s, Austria’s Social Democratic Party competed for political power against the Christian Social Party, which received strong clerical support. And in Austrian schools, religious instruction and practices, including priest-administered mass, confession, and processions, were mandatory. Quite aware of this reactionary context, Freud recognized that undoing the hold of religion would require, ultimately, transforming religion’s institutional foundations.

Sigmund Freud the Social Activist

Although Freud believed that the fundamental cause of irrational belief is the individual’s wish to believe, he was acutely aware that cultural norms and practices also predispose us to view the world irrationally—not only in the domain of religion but elsewhere in our lives as well. Hence Freud came to accept the view advanced by his social democratic colleagues and friends that private life is linked to social circumstance. In 1927, the year in which Freud’s “Future of an Illusion” was published, he signed on to a public manifesto announcing support for social democratic ideals and aims. But his progressive political affiliations began long before that. Freud’s close friend and collaborator Sandor Ferenczi was a social democratic activist, as was Margarete Hilferding, the first woman member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, and many other early psychoanalysts. Victor Adler, widely regarded as the “father of Austrian social democracy,” was Freud’s lifelong friend. Under Adler’s leadership, reformist and revolutionary tendencies in Austria united following the world war to create a democratic path forward that was independent of both Russian Communism and unfettered Western capitalism. In keeping with this hopeful vision, a passion was kindled in Freud for social justice. In 1918 he gave a speech in Budapest that was radically egalitarian in its aims and advocated for a militant social welfare program:

It is possible to foresee that at some time or other the conscience of society will awake and remind it that the poor men should have just as much right to assistance for his mind as he now has to the life-saving help offered by surgery…. When this happens, institutions or outpatient clinics will be started … such treatment will be free.

Europe’s psychoanalytic community welcomed this initiative. In cities such as Budapest, Vienna, Berlin, and London, clinics were set up that provided mental health services on a sliding scale and that, in Vienna for example, reached out to counsel the poor whose neighborhoods were distant from the wealthy and glamorous Ringstrasse at the center of the city.

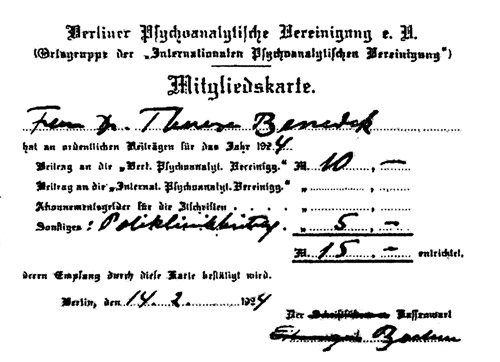

Therese Benedek’s membership card for the Berlin Psychoanalytic Society, including a 5 Kronen fee for support of the Society’s free Polyclinic. (Danto, Elizabeth Ann Danto. 2005. Freud’s Free Clinics: Psychoanalysis and Social Justice, 1918–1938. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 148)9

Among those whom the free clinics served in Austria and Germany were veterans returning from the First World War, many suffering from what we call today Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): terrifying flashbacks, chronic insomnia, tremors, loss of speech, inability to work, loss of affection for family and friends. These soldiers became scapegoats, accused by politicians and physicians alike of faking their symptoms and shirking their duties off as well as on the battlefield. Right-wing leaders and the popular press believed that Germany and Austria had lost the war because of a “Dolchstoss” (stab-in-the back) by domestic “enemies” who included not only social democrats but also these psychologically injured soldiers, whose symptoms were attributed to weakness of will and poor moral character. The standard treatments for these traumatized soldiers included solitary confinement, straight jackets, electrotherapy, and even brain surgery, aiming allegedly to restore them to sanity.

Freud and the first generation of psychoanalysts in Vienna took strong and public exception to these treatments. Freud wrote the introduction for the 1918 book Psychoanalysis and the War Neuroses, authored by four of his colleagues, which disputed the conventional victim-blaming account of war trauma. Then in 1920 Freud provided written and oral testimony in a court case involving mistreatment of war veterans. His judgment was unequivocal: Military doctors, not the foot soldiers, were the “immediate cause of all war neurosis.” During the war, Freud said, psychiatrists had “allowed their sense of power to make an appearance in a brutal fashion.” They had “acted like machine guns behind the front lines, forcing back the fleeing soldiers.” Freud did not shy away from the wider political implications of his public testimony: he vigorously supported Vienna’s progressive public health agenda and allied psychoanalysis with the wider social democratic movement that moved the city leftward in the post-war years.

Anna Freud’s Critique of Child-Raising Practices

Education as well as psychotherapy fell within the purview of the psychoanalytic movement Freud founded. His psychoanalytically-minded colleagues in the 1920s set out to reform all of the institutions in Vienna that were involved in raising and educating children. Among these activists was Freud’s own daughter Anna. From 1922 to 1927 she taught in an elementary school, and then followed in the footsteps of her father and became a psychoanalyst. With a declared commitment to serving Viennese families of all ethnic origins and class backgrounds, Anna Freud and the psychoanalytically minded community to which she belonged participated in the cultural revolution that became known as “Red Vienna.”

![Bebelhof apartment complex in Vienna, Photo by Buchhandler [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.skeptic.com/eskeptic/2017/images/17-12-13/Bebelhof_1930_Rondeau2-2x.jpg)

In the 1920s, Vienna’s municipal government became the largest landowner in the city and funded a massive project to provide public housing for the poor. Among the 370 so-called “people’s palaces” that were built, this one, Bebelhof, contained 301 apartments. Its interior courtyard, shown above, encouraged cooperative activities. Some of those served by the Psychoanalytic Association’s free clinic lived here. (Photo by Buchhändler [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

In 1925 Anna Freud co-founded an institute for the preparation of teachers in Vienna whose mission was to replace authoritarian methods of education with psychoanalytically-informed, more permissive ones. While Anna Freud was an admirer of educational reformers such as Maria Montessori, her psychological perspective went a step further: she took into account that, as her colleague D.W. Winnicott famously put it, “there is no such thing as a baby, there is always a baby and someone.” Anna Freud recognized the distorting influence of “countertransference” in adult-child relationships: parents, counselors, and teachers bring into their interactions with children their own unmet needs and anxieties.

In 1927 Anna Freud started a nursery for impoverished or neglected children under the age of three. Its mission was to learn directly from the children themselves and to develop humane, effective methods of treatment. Such treatment required, she believed, careful observation to confirm and disconfirm assumptions, staying alert to preconceptions about “what children need,” empathizing with children to understand their experience, and defending them when necessary against state, religious, and even parental authority. For over a decade Anna Freud was a leader in a “Children Seminar” in Vienna that discussed clinical cases and tested psychoanalytic theory against them. Although she remained largely loyal to her father’s language—language that did sometimes narrow her vision—she used that language more empirically, disregarding metaphysical implications of the orthodox terminology.

![A collage of Der Struwwelpeter illustrations [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.skeptic.com/eskeptic/2017/images/17-12-13/Heinrich-Hoffmann-Struwwelpeter-collage.jpg)

In “Lectures for Teachers,” Anna Freud referred to “Struwwelpeter” (Slovenly Peter), a children’s storybook immensely popular in Austria and Germany, to illustrate conventional ideas about raising children. (Heinrich Hoffmann [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons: 1, 2, 3)

First in Vienna and then in London where she relocated in 1938, Anna Freud moved psychoanalytic theory and therapy in new directions. She took into account the wide diversity of circumstances that shape human lives and disagreed with the view that all psychopathology originates in early sexual experience. Her approach to working with children was, of course, not unique. During the first half of the 20th-century, progressive education became in Europe and America a social movement embraced not only by teachers but also by psychologists, psychoanalysts, social workers, and parents. Although psychoanalytic principles, including an emphasis on family circumstances that influence children’s capacities to relate and learn, were not universally accepted within that movement, they contributed a great deal to the revolution.

Anna Freud became involved in legal reform as well: her writings on child custody issues, for example, which distinguish between a biological parent and what Anna Freud calls a “psychological parent” (an adult who is raising a child in a loving, thoughtful way and whom the child regards as a parent) were influential in revising family law in England and the United States.

An atheist like her father, Anna Freud confirmed his view in “Future of an Illusion” that humans can live fulfilling, altruistic lives without needing guidance from religion. She provided moral as well as intellectual guidance to her colleagues and students, and was considered by those who worked with her the warmest heart a child could ever hope to meet.

Anna Freud the Scientist

In Vienna’s Jackson Nursery, which opened in 1937 and was directed by Anna Freud, new staff members received not only a uniform but also pencil and paper which they were to use to record observations of the children they encountered: how they reacted to separations from their parents or other caretakers, how they related to other children, how they dealt with staff, how they coped with disappointment and anger, etc. These observations were then pooled and discussed by workers in the clinic—during breaks when the children were napping, for example. Gathered into case histories, these observations formed a basis for reflecting on explanatory constructs and for revising nursery policy.

When Anna Freud moved to London and administered the Hampstead War Nurseries and Clinic, she continued to emphasize direct and systematic observation. (Methodical child observation was pioneered as well by psychoanalyst Esther Bick, working at the Tavistock Clinic in London. Like Anna Freud, she was a Jewish refugee who came to England from Vienna.) The result was what we would today call a “database” consisting of thousands of individual case histories, broken down into distinct data fields and indexed by subject matter. Anna Freud explained:

What we hope to construct by this laborious method is something of a “collective analytic memory,” i.e., a storehouse of analytic material which places at the disposal of the single thinker and author an abundance of facts gathered by many, thereby transcending the narrow confines of individual experience and extending the possibilities for insightful study, for constructive comparisons between cases, for deductions and generalizations, and finally for extrapolations of theory from clinical therapeutic work.

Although Anna Freud recognized that observation is always theory-laden, she worked under the assumption that it is possible to suspend belief in one’s own views sufficiently to describe human situations in experience-near terms that are neutral between competing hypotheses. And in the Hampstead War Nurseries and Clinic, the detail in such observational description was sometimes quite fine-grained. For children impacted by “Blitzkrieg” air-raids during the London war years, for example, the observational protocol distinguished five kinds of anxiety, ranging from fear of a “real danger” to feelings that derived from other causes, including the emotional responses (calm/panicked, caring/self-centered) of parents to their children’s and to their own vulnerability. Beginning in the 1940s, many researchers made use of evidence provided by Hampstead clinical data. Anna Freud joined with Dorothy Burlingham in writing, for instance, War and Children (1943) and Infants Without Families (1944)—books that draw on Hampstead research and that refute common misconceptions about children’s responses to violence and loss.

Anna Freud on Human Irrationality

Like her father, but not captured as he was by metaphysical ideas about the nature of the mind, Anna Freud sought to understand the psychological mainsprings of reasoning gone awry. In 1936 she published The Ego and The Mechanisms of Defense, which elaborated ways in which people deny and disavow evidence they do not wish to see. Such machinery of the mind helps to explain collective as well as individual behavior. The concept of denial, for example, is exemplified today in the refusal to recognize the dangers of global warming and climate change. Projection and displacement are common in the scapegoating of immigrants. Anna Freud’s discussion of another defense, “identification with the aggressor,” is relevant to the popular appeal of fascist ideology. “By impersonating the aggressor,” she writes, “assuming his attributes or imitating his aggression, the child transforms himself from the person threatened into the person making the threat.” For example, a child who gets a shot in a doctor’s office goes home and, pretending to be the doctor, gives a shot to a doll or stuffed animal. By becoming the powerful agent who inflicts pain, the child masters feelings of smallness, fear, and anger.10

Such a dynamic, reproduced politically, can lead adults who feel victimized and powerless to identify with a charismatic, reassuring leader. Anna Freud’s book was published just as the forces of the extreme right were taking over in Austria. Her analysis of aggression would later be incorporated into psychoanalytic studies of “the authoritarian personality,” and it enters as well into the work of George Lakoff on the psychological origins of liberalism and conservatism. In such contemporary efforts to understand how deep fears and longings motivate political allegiances, the influence of the psychoanalytic tradition is unmistakable.

The Moral Arc

The voice of reason is a soft one,” wrote Sigmund Freud, “but it does not rest until it has gained a hearing.” The European skeptical tradition has for centuries exemplified that voice and stood against false hope and illusion, recommending instead a clear-minded encounter with reality that is capable of grasping and changing the circumstances of our lives. Since its invention at the turn of the 20th century in Vienna, psychoanalysis at its best has advanced this humanist project. And if certain cities in the past have been stars in a historical “moral arc” that “bends toward truth, justice, and freedom,”11 then Vienna in the years 1918–1934 must be counted as one of the most brilliant.

That star was extinguished when the Nazis came to power in Austria. But at the end of the Second World War, social democracy rose from the ashes and once again became influential in Europe. Psychoanalysis evolved too. Ironically, the dispersal during the 1930s of Vienna’s psychoanalytic community, which included many Jewish refugees, helped to distribute the theory and practice of “the talking cure” worldwide. In the many countries where these exiles settled, psychoanalysis developed in new directions. A fair evaluation will recognize the failings, but also the insights and accomplishments, of the research program that Sigmund Freud launched over a hundred years ago. ![]()

References & Notes

- Schaefer, Margret. 2017. “The Wizardry of Sigmund Freud.” Skeptic, Vol. 22, No. 3. http://bit.ly/2BrO9Cb

- There is indeed something of a Dr. Jekyll-Mr. Hyde character to Freud, who eloquently espoused ideals of human reason and scientific method, but then often failed to apply them. His life illustrates a basic psychoanalytic principle: human beings are apt to misperceive their own motives, powers, and prejudices.

- Although this article focuses on the contributions made by Anna Freud, the broad case against psychoanalysis is contradicted also by the achievements of other “pioneers” of psychoanalysis: Karen Horney, D.W. Winnicott, and Margaret Mahler, for example.

- The psychoanalytic tradition is shot through with contradictions on the subject of homosexuality. Anna and Sigmund Freud viewed homosexuality as deviant. Yet she, with the at least tacit approval of her father, lived with her partner Dorothy Burlingham for over five decades.

- Zaretsky, Eli. 2004. Secrets of the Soul. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Dailey, Anne C. 2017. Law and the Unconscious: A Psychoanalytic Perspective. Yale University.

- Freud considers religion only in its mainstream forms. He has little to say about theology—Spinoza’s pantheism, for example—that dispenses with a “God-the-Father” conception of the divine.

- Dennett, D. C. 1987. The Intentional Stance. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Benedek exemplified the unorthodox paths that, from the very beginning, women psychoanalysts would take. When Benedek was criticized for being too informal with those she saw in therapy (she said hello and goodbye and shook hands with them), she replied, “If I did not do that I would not be myself and that would not be good for my patient.” She wrote books on personality, depression, parenthood, and women’s sexuality.

- In the television series Breaking Bad, Walter White explains to his wife: “A guy opens his door and gets shot, and you think that’s me. No, I am the one who knocks!”

- Shermer, Michael. 2015. The Moral Arc: How Science Makes Us Better People. New York: Henry Holt.

About the Author

Raymond Barglow has a doctorate in philosophy from UC Berkeley and doctorate in psychology from the Wright Institute in Berkeley. He has taught at UC Berkeley and Trinity College and writes on science, ethics, and political issues.

This article was published on December 13, 2017.

Interesting article; thanks. But really, it does nothing to salvage psychoanalysis. What it shows is that Freud, father and in particular daughter, acted in an original, compassionate and enlightened way; and in so doing helped many. But this activity was minimally informed by psychoanalytic ways of thought. It was mirrored by many other individuals who hadn’t a psychoanalytic orientation at all. Which serves to show a psychoanalytic background is irrelevant to behaving like a compassionate, decent human being! Tho of course such a background isn’t inconsistent with compassionate actions. Simply unnecessary to them.

Marx surely would have been appalled by Stalin. But one can hardly think of a stronger reason to abandon a socio-economic theory than it failing horribly every time anybody actually bases a society’s economics on it, however noble the theory fonder’s intention were.

Instead, Marxists declare that the fault could not *possibly* be in Marxism itself. It was, yet again, “perverted”. They insist that, when reality does not fit with their theory, it is reality, not the theory, that has to be rejected and explained away.

Nothing shows that Marxism is not really an economict theory, but rather an unfalsifiable religious dogma, better than this.

>>>>Freud and Marx are similar in a way: some great insights, but some major oversights too.

That is true for most psychological and economic views, from Plato’s view of the mind to Sen’s current economic theories. It is hard to find out the truth about these subjects, and even the greatest thinkers in both fields make mistakes along with their insights.

But Marx and Freud were not great thinkers. They were dogmatic gurus. As Karl Popper pointed out, what made Freud and Marx in particular so popular is that their theories effortlessly – no yucky math, experiments, or data collection needed! – explain *everything* about *anything*.

This made them the 20th century’s replacement for revealed religion, the same role the imponderable German idealists’ psychological and social theories played in the 19th century. In fact, Marx *was* a German idealist; Marx’s theory is in effect a “secularized” version of Hegel’s abstruse philosophy of history, which goes a long way toward explaining its failure.

Popper pointed all this out in the early 20th century; today, after another (almost) 100 years of both Marxists’ and Freudians’ failure – Hegelians didn’t contribute much to historical research in the meantime, either – it is surely time to put to rest the massively inflated reputation of these frauds.

Dr. Small –

I’ve went to your interesting web site. Your recurring dream about wanting to urinate but finding no place to seems to me quite easy to solve, as I myself, and doubtless numerous others, have often had the same dream.

When our bladder is full, we often dream about wanting to urinate. But unless we are incontinent (or small children) we usually do not urinate in our sleep. So, naturally, we dream about wanting to urinate but not being able to, since that is precisely what we physically feel at the time. It is recurrent in my case due to me constantly drinking too much coffee too late at night.

What did Freud add? the “latent content” nonsense, where dreaming about wolves means you saw your parents having sex. No doubt Freud would have said that me having such a recurring dream is proof of an anal fixation I have with urine, due to overly-severe toilet training. I can make up such stuff as easily as Freud did. Anybody can.

Rhe problem with trying to analyze the human mind is that each one is different. An analogy is that the mind is the drive of the car while the brain is the car. If the car is not operating properly, it may be the fault of the drive or the car. Modern medicine is needed to determine which is at fault. It may, indeed, be a combination of both.

We all have dreams where our wishes or fears comes true; in fact, they are quite common. Freud’s free-association “latent content” dream interpretation, on the other hand, is based on nothing except his wild guesses.

Take the the wolf man’s dream, one of the two which launched dream interpretation, together with Irma’s injection. What the dream means – what Freud called the “manifest content” – is obvious. Little children are afraid of big, scary animals, and offen have nightmares about them. It would not at all surprise me if the child was read a fairy tale that had big bad wolves in it shortly before.

So what does Freud do? Declares that the “latent content” is – Surprise! – that the dreamer saw his parents having sex (Freud also adds the specific sexual position they used.) This is absurd nonsense, based on nothing more than Freud’s imagination, as are all his “latent content” “solutions” to dreams.

Besides, it isn’t even remotely new. Numerous cultures had seers who would solve and interpret dreams using free association, from the biblical Joseph onwards.

During 45 years of psychiatric practice I never found any of Freud’s theory useful. However I found dreams to be the royal road to the unconscious and have written about it on my website, hsmallmd.com. Thanks for a very useful paper and discussion.

Excellent piece, Dr. Barglow. A fine retort to the recent skeptic.com article touting Crews’ hatchet job on Freud. And your gentle, rational retorts to the instances of denial, aggression and subconscious motivation by your critiquers above are truly admirable. Kudos, sir.

Dr. Bargllow:

Einstein noted that instead of one set of physical quantities (space, time) being constant in all inertial reference frames, *another set* of physical quantities (the speed of light, the spacetime interval between events) are truly constant. Einstein’s physics is no more “relative” than Newtonian physics. It just has different invariants – which he used because, as you corretly note, it describe objective reality better.

But the analogy with cultural relativism is spurious. It is based only on the unfortunate name of his theory. Allegedly, Einstein was sorry later in life he named his view the “theory of relativity” instead of something like “on a new set of invariants”, because people used the misleading name of his theory to “prove” relativism in anything from logic to sociology.

I agree with everything you say here, Avital. The only point I was making in referring to Einstein is that the similarity or affinity of a view (in psychoanalysis as in physics) to a cultural fashion does not invalidate the rationality/justification for that view.

Freud’s psychoanalytic framework interacted with and was influenced by the turn-of-the century cultural Zeitgeist. Sexuality, hidden motivations, hypocrisy were very popular obsessions at that time, and they inform and misinform Freud’s work. That contextualization neither proves nor invalidates the core proposition of psychoanalysis: that people are often driven by unacknowledged motives and distant memories. Perhaps you will agree with that moderate degree of separation of conjecture (e.g. in physics or psychoanalysis) and culture.

That said, Einstein’s theory is of course VERY different in its scientific character and supporting evidence from that of Freud! I didn’t mean to suggest otherwise.

One final observation. Freud idea of “resistance” or “denial” itself often becomes just a psesudo-sophisticated way of denial: we hold *our* political and social views rationally, of course; *they* hold *their* views irrationally, due to their unaware mind, which therapy will cure. This amounts to the same thing as saying that they are possessed by the devil, and we should pray that St. Freud will show them the light.

In the old USSR, for example, dissidents were put into mental institutions – not to punish them, but to cure the “denial” and “resistance” that made them hold the delusional belief that Marx might have been wrong about something. Similarly, in the USA, the seasonal moral panics about anything from communists to domestic sexual abuse are inevitably accompanied by claims that those who do not join the hysteria are “in denial”.

Whenever one believes that one holds a rational, justified view and that someone else is mistaken, there is the risk of being dead wrong about that: we “pray,” as you say, that they will one day see “the light,” but it turns out that we are the ones in darkness! Freud was often mistaken, and too quickly and easily attributed views contrary to his own as “resistance.” Point well taken.

With regard to the USSR and Marxism, I agree with you there also. Well … not entirely. Karl Marx would, I believe, have shuddered at the twisted interpretations of his views that Stalinists gave. Freud and Marx are similar in a way: some great insights, but some major oversights too. Of course, that’s easy for us to say, looking back historically and noting the craziness that has been done in the names of both of these Founders.

Freud “theory of dreams” was summed up nicely by Piet Hein in one of his “grooks”:

Everything’s either

Concave or convex

So whatever you dream

Will be about sex.

Hello Avital. Thanks for your multiple responses. I find much to agree with in them. But not everything. With regard to sexuality in dreams, yes, Freud is obsessed with that, and it warps his view of dreams. On the other hand, out of the hundreds of dreams he discusses in his classic work, “The Interpretation of Dreams,” many of them – most of them, I dare say – have nothing to do with sex at all. The wish they express, if there is one, is not a sexual one. For example, the most discussed dream in the history of psychoanalysis – Freud’s so-called “Irma Dream” – expresses the wish to hold himself blameless for the failure of a treatment he administered to a patient. Sex enters into that dream hardly at all. Now, it may be that Freud is repressing or suppressing themes in the dream that are sexual in nature. But the anxieties and aims and references of the dream don’t appear to be sexual ones, and Freud does not represent them as such.

As for Szasz’s denial of mental illness, Prof. Sidney Morgenbesser quipped, “He thinks mental illness is all in our head”.

As for Freud, theproblem with Freud is that his theories were good and original, but the original part was not good and the good part wasn’t original.

That humans are often controlled by passions or often self-deluded is an ancient observation, going back at least to Plato if not to prehistorical times. So is trying to discover hidden truths about ourselves by dialogue, the famous division of the mind into three parts, or the view that realizing our irrationality is important.

But Socrates or, say, Epictetus, would never have suggested to someone who came to them for wisdom that their source of unhappiness is an unconscious desire to kill their father and have sex with their mother. Not would they have bothered with the patient’s dreams, at least not using Freud’s absurd attempts to make all dreams “really” about sex.

To be sure, modern psychology can do therapy better than the ancient stoics or other philosophers, because we know more about the mind than they did, empirically. But Frued just retarded the progress.

As I see it now: The folk concepts of mental experience of the pre-industrial ages had become inadequate to describe common experience…Freud supplied new folk concepts such as “ego” and “unconscious mind” and “transference” much of which were able to gradually enter the folk-world. Most Western concepts are framed as nouns, things, rather than verbs, functions. These memes propagated as they were more in tune with the times, not because they were accurate. Now in the Info Age the descriptive concepts are changing again…and hopefully will be more useful!

Hello Valerie, Your comment illustrates the way in which “folk concepts,” as you call them, evolve. And often, as you also say, they changed over time because they were “more in tune with the times, not because they were accurate.” But sometimes explanatory concepts evolve because they ARE more accurate then those of the past.

Consider the concept of relativity in physics. Einstein replaced absolute space, time, and velocity with relative counterparts of these concepts. And yes, this was “more in tune with the times”: Absolute moral standards, artistic standards, social norms were also challenged at the turn of the past century. Cultural relativism deemed such standards and norms valid only relative to a particular society. Similarly, space, time, and velocity could exist, thought Einstein, only relative to a particular frame of reference. But this parallel between cultural relativism and relativity in physics shouldn’t obscure the fact that Einstein’s theory represented an objective advance over that of Newton.

The same can said of some of Freud’s ideas – about “unconscious” motives, “transference,” and the like. Yes, these ideas were “more in tune with the times,” as you say. But they also advanced human understanding of the mind. And that had big consequences. One example that I give in the article is the raising of children. Our “folk” understanding today of what children need in order to flourish is very different, and reflects a deeper understanding, than conventional (Western) child-raising concepts a century ago. The punitive regimen back then was not optimal for children.

To be sure, not all parents treat their children better today than parents did in the past. But we have made some progress. Although that improvement didn’t result just from the psychoanalytic tradition, people like Anna Freud did contribute to a much needed re-evaluation of parent-child relationships.

I entirely agree, Raymond. Progress, while not inevitable, is quite likely when it is intended. But I know many people who still explain everything within Freud’s “weltanshaung”. Thank you for responding to your commenters, it is kind and thoughtful. I have other relevant thoughts floating around in my “mind,” but I have let this go too long as it is and need even more time to articulate. For instance, many writers use the words ‘mind’ and ‘brain’ interchangably, whereas there are neurons in other areas that influence those in the brain. I observe this just beginning to be culturally accepted!

What about the criticism of Thomas Szasz on Freud? How do you rate that ?

Hello Innaiah,

Thomas Szasz makes the telling point that mental disability is not best viewed as just a MEDICAL illness. Also spot-on are some of his other criticisms of orthodox psychoanalysis and psychiatry. As I mention in the article, “In some parts of the world, including the United States, psychoanalysis became during the 20th century an enterprise governed by a medical elite that was self-serving and dogmatic.”

But Szasz went way overboard, claiming that the very idea of mental illness is a hoax, or rather a “myth,” as he indicates in the title of his most famous book, The Myth of Mental Illness. People who live with or treat people with severe mental pathology know that such a claim is not only false but dangerous. There are people so troubled that they desperately need help. They aren’t just expressing themselves in a way that is “unusual,” or “creative.” Talk therapy works effectively to help some of them. Medication may help as well. But Szasz’s dismissal of such efforts is no help at all.

Barglow thinks he has an answer for everyone. He is more interested in protecting Freud’s reputation than in arriving at truth.

Has psychoanalysis now been established “in an open-minded, evidence-based way”? It never has been, yet it continues to be practiced as therapy. Allowing mentally disturbed people to talk about their problems may be helpful, but this is not unique to Freudian psychoanalysis. If it forces them to construct false memories to conform to dogma it may do more harm than good. Nor is the dependence on the analyst constructive.

To move past the false path that Freud set psychology on it is probably necessary to demythologize the person. There has probably been more scientific progress when Freud’s non-scientific path was simply disregarded.

Hello Skeptonomist,

I appreciate that you speak in a more cautious tone than the totally dismissive Freud critics.

You do speak of psychoanalysis, it seems to me, as if it were a single unified doctrine. You refer, for example, to “the false path that Freud set psychology on.” But Freud inaugurated a framework that informed diverse and often divergent paths! Melanie Klein and Anna Freud were at loggerheads. Wilhelm Reich was quite an outlier. Heinz Kohut and Otto Kernberg disagreed radically. But from the many controversies that belong to the psychoanalytic tradition, we have learned a lot, I believe. I mentioned some of these advances in the article. They have deepened our understanding of the mind, it seems to me.

From footnote #7:

“Freud considers religion only in its mainstream forms. He has little to say about theology—Spinoza’s pantheism, for example—that dispenses with a “God-the-Father” conception of the divine.”

It’s not just Freud who clings to this particular consideration. Shermer, the various writers appearing on these pages, self-proclaimed skeptics, proud atheists alike all appear to be afflicted with this particular form of blindness. By “mainstream” I assume a rather narrow, Judeo-Christian, authoritarian, patriarchal form is meant, or so it seems when “religion” is frequently condemned here. Many here would do well to open their minds a little bit, broaden their views and understanding of all that may be conveyed by the term “religion”.

Hello Joe,

I consigned to a footnote a comment about Freud’s view of religion that merits more consideration. Religion has many forms, as you say.

An excellent discussion of parallels between psychoanalysis and Buddhism is offered by Mark Epstein in his book, Thoughts Without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective.

For decades Freud was a good friend of Oskar Pfister, a Swiss Protestant pastor whom he respected a good deal. (They exchanged letters with one another for 30 years!) In Freud’s “New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis,” he acknowledged that “certain mystical practices” might provide deep insight into the mind.

Thank you, Raymond, for taking the time to respond (and for your generally polite and engaging mode of response to other commenters). I appreciate you elaborating a bit on Freud’s views of religion, and am glad to know that he thought “certain mystical practices” might have value.

I have not heard of the Epstein book but its title suggests I might find it appealing. Thank you for that recommendation and your thoughts.

It is very easy to speak ill of Freud today. Thanks to the Crews exposé, we know even more than ever about Freud’s failings as a scientist and human being. He was indeed a liar and a fraud. He did harm to his patients. He was a misogynist. The list goes on. One maddening thing about Freud is his hypocrisy and inconsistent standards for himself and other people. He decried Jung’s occultism but harbored his own occult ideas. He could psychoanalyze other professionals, but for him a cigar was just a cigar. One could not criticize him without being accused of being a father-murderer.

It is much more difficult to find anything positive to say about Freud. I therefore appreciate Raymond Barglow’s efforts to balance the negative with some positives.

Human beings, including Freud, are neither totally good nor totally bad. Any portrayal of Freud in totally black and white terms is almost guaranteed to be inaccurate.

Unbelievable. RAYMOND BARGLOW—a true believer.

There is a big difference between the THEORIES of Freud about human mental processes and the TECHNIQUE of treatment Freud developed. His THEORIES are of vast importance to the understanding of human motivations, but his METHODS of treatment are almost useless. This distinction should be kept in mind in any critique of his work.

The task of psychological science should be to figure out how these theories relate to known biophysical facts of the human organism. From that, someday, an effective form of treatment may possibly be developed. Without taking Freud’s theories into account, that will never happen.

Hello Tzindaro,

You recognize the possible value of Freud’s ideas but add that “his METHODS of treatment are almost useless.”

I take it you’re referring to “the talking cure.” It seems to me that the kind of talking that goes on in therapy of this kind can be of value. Sometimes, in the absence of conversation, when we only dimly, if at all, understand our own hopes, fears and feelings about others and ourselves, we act in irrational, destructive ways. Now, one remedy may be to take a medication. And yes, that can help a lot! But Freud and the psychoanalytic tradition explored a different kind of remedy: listening to a person, and doing so with understanding and empathy. That’s not a “cure” for everyone in every situation, to be sure. But it does work very well sometimes.

You may reply that this idea is commonplace — by no means unique to Freud and psychoanalysis. But this non-stigmatizing, non-medicalizing approach to understanding and treating mental problems was much more controversial in Freud’s day.

Perhaps you are referring in your criticism to the “self-fulfilling prophecy” character of some psychoanalytic interpretation: Objections to such interpretation may be dismissed as psychological “resistance.” That is a problem, and it is one that many psychoanalysts themselves have drawn attention to and sought to correct. In psychoanalysis as in any field of empirical inquiry, we may read our own prejudices into the information given by observation. But many psychoanalytically minded teachers and therapists today are aware of such confirmation bias. It even has a technical name: “counter-transference.”

I’m also not a fan of the idea that we glorify one person’s work or viewpoints and call it science. As Obi Wan would say “Who’s the more foolish, the fool, or the fool that follows him” (Yes, I know Old Ben ain’t real ? but the quote works).

I see that the article was attempting to include the work of others along with both Freuds but I still think they are given more credit than they are due. Some of their deeply flawed or distorted thought processes have remained unchallenged and taken for granted as truth.

Good morning Jennifer MacDonald,

All I’m asking is that skepticism be balanced by consideration of the contributions that the psychoanalytic tradition has made.

You write: “I see that the article was attempting to include the work of others along with both Freuds but I still think they are given more credit than they are due. Some of their deeply flawed or distorted thought processes have remained unchallenged and taken for granted as truth.”

For the most part I find Anna Freud’s work empirically based and illuminating. In some ways, our understanding of children, including what they need to grow up creative and healthy, has improved over the past century. And people like Anna Freud contributed to that improvement.

Women have been very prominent in the psychoanalytic tradition from the beginning. I mentioned some of them in the article, and there are many more. They criticized what was crazy in Freud — all the stuff about “penis envy” and the like. I suggest in the article that “Feminists such as Juliet Mitchell, Nancy Chodorow, and Jessica Benjamin rejected the assumptions made by mainstream psychoanalysis about women’s and men’s ‘normal’ roles and behaviors; yet they found psychoanalytic concepts useful for understanding the childhood origins of gender differences and the devaluation of women’s lives.”

We’ve seen that devaluation highlighted in recent news about the mistreatment of women by men in positions of power. (Just yesterday, Roy Moore was defeated in Alabama.) Feminist contributions drawing upon and elaborating psychoanalytic insights can help us to understand human sexuality better.

A truly disgusting polemical attempt to rescue Freud, a fraud for the ages. When you invoked Kahneman , and said that Freud anticipated “Thinking Fast and Slow,” I felt sick to my stomach. Psychology with its non-empirical and constantly shifting theories, has infected our schools, our courts, and our businesses. IQ tests, personality tests, and “clinical expertise” are all irrational and do not hold up under skeptical inquiry.

That was my fast thinking reaction to your article. Slowing down, I can see that you want people like Frederick Crews and me to slow down in our criticism of the psychanalytic movement. You might be right about that.

But I don’t think so. The poisoned fruit created by that Cocaine addict, Freud, has infected all of us. What if there is no such thing as an ego? What if the unconscious mind doesn’t exist? These are proper questions for skeptics like us to be asking.

Thank you for sharing that. I appreciate it because I’ve always had a vague idea that there is something not quite sound about that entire psychoanalysis and therapy method based on Freud’s work. As more people become willing to challenge the ideas of Freud and the impact it has had on at least, the western culture, the more we gain freedom from the ridiculous concepts of what it means to be human. Yes, what if the ego isn’t real? And I have yet to find the quality of trying to uncover the secrets of my subconscious because quite likely there are none. Whew!

Good morning Dr. Hall,

As I mentioned in a previous comment, I too have read Crews’ book. Crews focuses on the first half of Freud’s life, before he was appointed professor in 1902. But I believe Freud did “clean up his act” considerably thereafter. You say that “he got almost everything wrong.” I’m glad you said “almost.” Consider the essay he wrote, “Future of an Illusion,” which I discuss in the article. His understanding of religion is illuminating, it seems to me. And for all of his faults, Freud did elaborate the idea that is fundamental to psychoanalysis in all of its forms, namely that “humans are inclined, by nature and by nurture, to mistake their reasons for believing and acting … we are fallible in this manner, mentally conflicted and influenced in ways that we only partly understand. ” This idea wasn’t original with Freud, to be sure, but he did draw attention to it, illustrate it with many and diverse examples, and it became the basis for doing psychotherapy in a new way. (Yes, some of his examples have been debunked — but others do accurately exemplify the way the mind works.)

So I don’t entirely disagree with your negative evaluation of Freud. As I mention in a footnote: “His life illustrates a basic psychoanalytic principle: human beings are apt to misperceive their own motives, powers, and prejudices.

Hello Michael Strauss,

You conclude your comment by saying, “What if there is no such thing as an ego? What if the unconscious mind doesn’t exist? These are proper questions for skeptics like us to be asking.”

I agree with you that these are good questions. “Ego” is something of a mistranslation of the German word that Freud used, “Ich,” which is simply the first person singular pronoun “I.” When we use that pronoun, it seems to me that there is SOMETHING we are referring to.

Now, was Freud’s view of “I” false? I don’t believe there is a simple yes or no answer. The school of “ego psychology” that was inspired by Freud’s work did make significant contributions, it seems to me, to understanding human rationality and irrationality.

Does the “unconscious mind” exist, you ask. Certainly there is mental processing going on in us that is not — or at least not entirely — conscious. I believe you will agree to that. What Freud was getting at is that, as I say in the article, “humans are inclined, by nature and by nurture, to mistake their reasons for believing and acting…. he made this ‘diagnosis’ of the human condition the basis for doing psychotherapy in a new way.”

In brief, we are inclined (not always, but quite often, it seems to me) to mistake our own motives — are you willing to go this far with Freud?

I would recommend that Dr. Barglow read the recently published book (Freud: The Making of an Illusion” by Fred Crews. It is a comprehensive and devastating critique of both the man and the theory. In my view, the psychoanalytic movement was responsible for keeping psychological theory in the dark ages. It is entirely empirically unsupportable and built upon failed clinical experiences.

john S Searles, Ph.D.

I reviewed Crews’ book for Science-Based Medicine just yesterday.

https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/freud-was-a-fraud-a-triumph-of-pseudoscience/

It exposes Freud as a fraud, a misogynist, and a liar. And he believed in numerology, the paranormal, and occultism. He was anything but a skeptic. His ideas were very influential, but he got almost everything wrong.

Good morning Dr. Searles,

I have indeed read the Crews book, and my essay was prompted in part by what he has to say. While his critique is a telling one, it seems to me one-sided. Within the “dark ages,” as you call them, there is also some light, and I wish to draw attention to that.

I have documented in the article the commitment of Anna Freud, for example, to scientific method. She was quite unlike her father in that respect. And in large degree she practiced what she preached. Or so it seems to me. Do you disagree.

By the way, I very much appreciate the many contributions you have made to helping us understand and respond to alcoholism.

As I recall, Crews documents Anna Freud’s efforts to suppress much of the work that showed that her father was an ineffective and occasionally iatrogenic therapist. While I appreciate your attempt to “find the pony” in the pile, I remain skeptical (how appropriate!).