Over the weekend of august 12–14, 2001, I participated in an event entitled “Humanity 3000,” whose mission it was to bring together “prominent thinkers from around the world in a multidisciplinary framework to ponder issues that are most likely to have a significant impact on the long-term future of humanity.” Sponsored by the Foundation for the Future—a nonprofit think tank in Seattle founded by aerospace engineer and benefactor Walter P. Kistler—long-term is defined as a millennium. We were tasked with the job of prognosticating what the world will be like in the year 3000.

Yeah, sure. As Yogi Berra said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” If such a workshop were held in 1950 would anyone have anticipated the World Wide Web? If we cannot prognosticate fifty years in the future, what chance do we have of saying anything significant about a date 20 times more distant? And please note the date of this conference—needless to say, not one of us realized that we were a month away from the event that would redefine the modern world with a date that will live in infamy. It was a fool’s invitation, which I accepted with relish. Who could resist sitting around a room talking about the most interesting questions of our time, and possibly future times, with a bunch of really smart and interesting people. To name but a few with whom I shared beliefs and beer: science writer Ronald Bailey, environmentalist Connie Barlow, twin research expert Thomas Bouchard, brain specialist William Calvin, educational psychologist Arthur Jensen, mathematician and critic Norman Levitt, memory expert Elizabeth Loftus, evolutionary biologist Edward O. Wilson, and many others, all highly regarded in their fields, well published, often controversial, and always relevant.

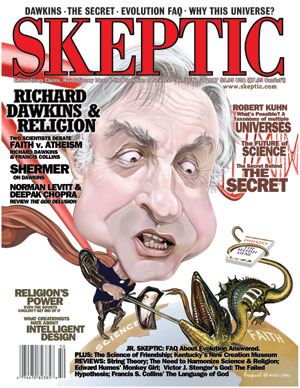

Also in attendance, there to receive the $100,000 Kistler Prize “for original work that investigates the social implications of genetics,” was the Oxford University evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins. (Ed Wilson was the previous year’s winner and was there to co-present the award, along with Walter Kistler, to Richard.) Dawkins was awarded a gold medal and a check for his work “that redirected the focus of the ‘levels of selection’ debate away from the individual animal as the unit of evolution to the genes, and what he has called their extended phenotypes.” Simultaneously, the award description continues, Dawkins “applied a Darwinian view to culture through the concept of memes as replicators of culture.” Finally, “Dr. Dawkins’ contribution to a new understanding of the relationship between the human genome and society is that both the gene and the meme are replicators that mutate and compete in parallel and interacting struggles for their own propagation.” The prize ceremony was followed by a brilliant acceptance speech by Richard, who never fails to deliver in his role as a public intellectual (the number one public intellectual in England, according to Prospect magazine) and spokesperson for the public understanding of science.

This is not what most impressed me about Richard, however, since any professional would be expected to shine in a public forum, especially with a six-figure motivator hanging around his neck. It was during the two full days of round-table discussions, breakout sessions, fishbowl debates, and (most interestingly) coffee-break chats, where Richard stood out head-and-shoulders above this august crowd. Despite his reputation as a massive egotist, Richard is, in fact, somewhat shy and quiet, a man who listens carefully, thinks through what he wants to say, and then says it with an economy of words that is a model for any would-be opinion editorialist. In one session, for example, we were to debate “Conscious Evolution—Fantasy or Fact?” After about 20 minutes of discussion of a topic none of us had carefully defined, Richard spoke up:

I wanted to listen around the table to see if I could make out what conscious evolution is. I still haven’t. It seems to be a mix-up of two, or three, or four very different things. There is the evolution of consciousness; there is what Julian Huxley would have called “consciousness of evolution” or, the way he put it was “man is evolution become conscious of itself.” But entirely separate from that…forget about consciousness and just talk about deliberate control of evolution, and then we bifurcate again into two entirely different kinds of evolution. That is genetic evolution and cultural evolution. I am not going to utter the “m” word [memes]; everybody else keeps saying it and then looking at me, and I am going to duck out of that. I used not to think this, but I am increasingly thinking that nothing but confusion arises from confounding genetic evolution with cultural evolution, unless you are very careful about what you are doing and don’t talk as though they are somehow just different aspects of the same phenomenon. Or, if they are different aspects of the same phenomenon, then let’s hear a good case for regarding them as such.

The first response was from the futurist Michael Marien, who said: “I would like to start back at the point where Richard Dawkins honestly said he had never heard the term conscious evolution. Sometimes a statement of ignorance can be very illuminating.” Indeed it can be, and Richard’s candid comments throughout the weekend illuminated the conference like no one else’s.

Outside of additional specifics of what Richard said, here is my overall impression of that weekend in Seattle, an observation with broader implications for Dawkins’ impact on science and culture: a discussion would ensue over some issue, such as “the factors most critical to the long-term future of humanity,” and most of us panelists would jump in with our opinions, banter some particular theme back and forth for awhile, then leap to another topic, hammer that into the faux-mahogany table, and so forth round and round. Richard would sit there listening, processing our long-winded verbosities, select his moment to lean forward and make a short observational remark or inductive inference, then sit back and collect more data. It was what happened after Richard spoke that I came to realize this is a man on a different plane, above even these stellar minds. The conversation changed, bifurcated in a new direction, with references to its source. “You know, Richard has a point…” “I’d like to comment on Richard’s observation…” “Going back to what Professor Dawkins said…” And so on. Richard Dawkins changed the conversation. He has been changing the conversation ever since 1976, when his book The Selfish Gene changed the way we look at ourselves and our world.

* * *

Humans are a hierarchical social primate species who, despite centuries of democratic rule, still long to sort themselves into pecking orders within families, schools, peer groups, social clubs, corporations, and societies. We can’t help it. It is in our nature, courtesy of natural selection operating in the social sphere. As an intellectual social movement with which I am intimately involved, skepticism is subject to the same hierarchical social forces. As such, we scientists and skeptics look up to and model ourselves after our alpha leaders. In my own intellectual development there have been several who served me well in this capacity, including Carl Sagan, Stephen Jay Gould, and Richard Dawkins. They are, in fact, candles in the darkness of our demon-haunted world (in Carl’s apt phrase from his skeptical manifesto). Lamentably, we lost Carl and Steve too early. How I long for one more poetic narrative on our pale blue dot in the vast cosmos, or one more elegant essay on life’s complexity and history’s contingency.

But thank the fates and his hearty DNA that we still have Richard, who stands as a beacon of scientific skepticism and a hero to skeptics around the world. Dawkins’ work has touched the skeptical movement in three areas of common concern: pseudoscience, creationism, and religion.

Dawkins’ primary work on pseudoscience is Unweaving the Rainbow, a collection of essays centered on “Science, Delusion and the Appetite for Wonder” (the book’s subtitle). Here we see almost no limits to the breadth of Richard’s interests, as he skeptically analyzes astrology, coincidences, conjurors, eyewitness accounts, fairies, flying saucers, the Gaia hypothesis, gambling fallacies, hallucinations, horoscopes, illusion, imagination, intuition, miracles, mysticism, paranormalism, post-modernism, psychic phenomena, reincarnation, Scientology, superstition, telepathy, and even The X-Files. Richard’s analysis of these and other delusions is not debunking as such, but more positively directed toward helping us better grasp what science is by looking at what science isn’t; and how we can recognize good science by seeing bad science for what it is. Deeper still is the take-home message embodied in the book’s title from Keats, “who believed that Newton had destroyed all the poetry of the rainbow by reducing it to the prismatic colours. Keats could hardly have been more wrong.” In his stead Richard offers us this insight: “I believe that an orderly universe, one indifferent to human preoccupations, in which everything has an explanation even if we still have a long way to go before we find it, is a more beautiful, more wonderful place than a universe tricked out with capricious, ad hoc magic.”

Creationism is a form of pseudoscience, and the connection here is an obvious one for an evolutionary biologist who holds the job title of “Professor of the Public Understanding of Science.” In America, at least, there is no more public misunderstanding of science than creationism, and Richard has written broadly and deeply on the subject, and he minces no words (and it is with creationists especially that Richard does not “suffer fools gladly,” as he has been accused). After the May, 2005, hearings in Kansas on the proposed introduction of “Intelligent Design” into the public school science curriculum, Dawkins fired off an opinion editorial in The Times (London) on May 21, entitled “Creationism: God’s Gift to the Ignorant,” that included this poignant observation that cut through yards of creationist verbiage with clarity and wit:

The standard methodology of creationists is to find some phenomenon in nature that Darwinism cannot readily explain. Darwin said: “If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down.” Creationists mine ignorance and uncertainty in order to abuse his challenge. “Bet you can’t tell me how the elbow joint of the lesser spotted weasel frog evolved by slow gradual degrees?” If the scientist fails to give an immediate and comprehensive answer, a default conclusion is drawn: “Right, then, the alternative theory, ‘intelligent design’, wins by default.”

At least three of Richard’s books—The Blind Watchmaker, Climbing Mount Improbable, and River Out of Eden—are direct challenges to creationists’ arguments, although presented not as straight debunking works, but as science advancing treatises on evolutionary theory. And Richard’s latest book, The Ancestor’s Tale, is one long answer to creationists’ demand to “show me just one transitional fossil.” Dawkins traces innumerable transitional forms, or what he calls “concestors”—the “point of rendezvous” of the last common ancestor shared by a set of species—from Homo sapiens back four billion years to the origin of heredity and the emergence of evolution. No one concestor proves that evolution happened, but together they reveal a majestic story of process over time. Richard is the Geoffrey Chaucer of life’s history, and our most articulate public defender of evolution.

Creationism, of course, is nothing more than thinly disguised religion masquerading as science, in order to attempt an end-run around the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment prohibition on government establishment of religion. Richard’s views on religion, particularly when it intersects with science, are so public and controversial that they have even inspired a book by the Oxford University professor of historical theology, Alister McGrath, Dawkins’ God (Blackwell, 2004), a book I reviewed in Science (8 April 2005, 205–206). According to Dawkins the connection between science and religion runs like this: Before Darwin, the default explanation for the apparent design found in nature was a top-down designer, God. The 18th-century English theologian, William Paley, formulated this into the infamous watchmaker argument: If one stumbled upon a watch on a heath, one would not assume it had always been there, as one might with a stone. A watch implies a watchmaker. Design implies a designer. Darwin provided a scientific explanation of design from the bottom up: natural selection. Since then, arguably no one has done more to make the case for bottom-up design than Dawkins, particularly in The Blind Watchmaker, a direct challenge to Paley. But if design comes naturally from the bottom up and not supernaturally from the top down, what place, then, for God?

Although most scientists avoid the question altogether, or take a conciliatory stance along the lines of Stephen Jay Gould’s non-overlapping magisteria (NOMA), Dawkins unequivocally states in The Blind Watchmaker: “Darwin made it possible to be an intellectually fulfilled atheist.” And in River Out of Eden: “The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind pitiless indifference.”

Herein lies the crux of the issue, and Dawkins brooks no theological obfuscation. For example, after debunking all the quasi-scientific and pseudoscientific arguments allegedly proving God’s existence, scientists are told by theologians like Alister McGrath that we should come to know God through faith. But what does that mean, exactly? In The Selfish Gene, Dawkins wrote that faith “means blind trust, in the absence of evidence, even in the teeth of evidence.” This, says McGrath, “bears little relation to any religious (or any other) sense of the word.” In its stead McGrath presents the definition of faith by the Anglican theologian W. H. Griffith-Thomas: “It commences with the conviction of the mind based on adequate evidence; it continues in the confidence of the heart or emotions based on conviction, and it is crowned in the consent of the will, by means of which the conviction and confidence are expressed in conduct.” Such a definition—which McGrath describes as “typical of any Christian writer”—is what Dawkins, in reference to French postmodernists, calls “continental obscurantism.” Most of it describes the psychology of belief. The only clause of relevance to a scientist is “adequate evidence,” which raises the follow-up question, “Is there?” Dawkins’ answer is an unequivocal “No.”

* * *

Does a scientific and evolutionary worldview such as that proffered by Richard Dawkins obviate a sense of spirituality? I think not. If we define spirituality as a sense of awe and wonder about the grandeur of life and the cosmos, then science has much to offer. As proof, I shall close with a final story about Richard, and a moment we shared inside the dome of the 100-inch telescope atop Mt. Wilson in Southern California. It was in this very dome, on October 6, 1923, that Edwin Hubble first realized that the fuzzy patches he was observing were not “nebula” within the Milky Way galaxy, but were separate galaxies, and that the universe is bigger than anyone imagined, a lot bigger. Hubble subsequently discovered through this same telescope that those galaxies are all red-shifted—their light is receding from us and thus stretched toward the red end of the electromagnetic spectrum—meaning that all galaxies are expanding away from one another, the result of a spectacular explosion that marked the birth of the universe. It was the first empirical data indicating that the universe had a beginning, and thus was not eternal. What could be more awe-inspiring—more numinous, magical, spiritual— than this cosmic visage of deep time and deep space?

Skeptic magazine 13.2 (2007)

Available digitally only

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Since I live in Altadena, on the edge of a cliff in the foothills of the San Gabriel mountains atop which Mt. Wilson rests, I have had many occasions to make the trek to the telescopes. In November, 2004, I arranged for a visit to the observatory for Richard, who was in town on a book tour for The Ancestor’s Tale. As we were standing beneath the magnificent dome housing the 100-inch telescope, and reflecting on how marvelous, even miraculous, this scientistic vision of the cosmos and our place in it all seemed, Richard turned to me and said, “All of this makes me so proud of our species that it almost brings me to tears.”

I can only echo the same sentiment about the works and words of Richard Dawkins. ![]()

This article was published on March 26, 2021.

Thank you Professor Richard Dawkins, for your book The Selfish Gene and others rescued me from religions delusions

Wow!