The 1933 and 2005 versions of King Kong share many rich details, and a moral. There are those who suggest that moral must be something about the power of love, but I suggest the moral is this:

“Never, ever go to Skull Island.”

Skull Island, the setting for the second act of King Kong, is an utterly nightmarish place. A steaming jungle packed with prehistoric beasts and crawling with unlikely monsters, it is a place where even the insects can drag you away for dinner.

It’s not surprising that this exotic, terrifying place awed Depression-era movie audiences. When Kong opened in 1933, no one had ever seen anything like it. The revolutionary special effects, the scope of imagination, the depth of immersion in another world — all these created a blockbuster experience that still echoes in the popular imagination today.

My story begins on another, sleepier island : Vancouver Island, off the western coast of British Columbia, Canada.

At the southern tip lies the provincial capital city of Victoria, a bustling tourist destination with a busy cruise ship port. Today it bills itself as “the City of Gardens,” but in 1933 it enjoyed worldwide fame for something altogether more mysterious — nothing less than an 80-foot sea monster, called Cadborosaurus.

According to legend, an awesome, primeval monster — a huge serpent with flippers, a mane, and a head something like that of a camel or horse — slides undetected through the frigid waters off British Columbia and Washington State. Could a living dinosaur, a monster out of time, lurk here beneath the waves?

That question hinges on a moment in history.

Imagine yourself in 1933 for a moment. The Great Depression was causing tremendous hardship at home, while daily newspaper headlines carried ever more bad news about Adolf Hitler. As tensions continued to mount between the new Nazi government of Germany and the rest of Europe, war seemed increasingly likely.

The news featured one bummer story after another, and people needed a pick-me-up. In Victoria, that came in the form of headlines proclaiming, “Yachtsmen Tell Of Huge Serpent Seen Off Victoria.”

Two civil servants, named Langley and Kemp, told the Victoria Daily Times that they’d each independently seen huge sea monsters. According to Langley, he and his wife were out sailing when they heard “a grunt and a snort accompanied by a huge hiss,” and then “saw a huge object about 90 to 100 feet off,” of which “[t]he only part of it that we saw was a huge dome of what was apparently a portion of its back.” It was, he said, only visible for a few seconds before diving.

What strikes me about Langley’s monster — and contemporary critics were quick to point this out — is that it swam like a whale, it sounded like a whale, and it looked a whale. Now, whales definitely live in the area: Humpbacks, grey whales, sperm whales, and others. Even today, boatloads of whale-watching tourists leave Victoria’s downtown Inner Harbour every few minutes. Given that we have no data here except a momentary, unsubstantiated, undeniably whale-like anecdote, the Langley sighting seems to me to be a completely trivial case.

But the Kemp case was more interesting. It was his sustained daylight sighting that fueled a Cadborosaurus media frenzy in Victoria and across the continent, inspiring a rash of copycat sightings — and launching an enduring legend.

According to Kemp’s 1933 story, he and his family were picnicking one afternoon in the previous year, on a group of tiny islands just off Victoria, when they saw something extraordinary. A huge creature swam up the channel between Chatham and Strongtide Islands leaving an impressive wake. Kemp recalled, “The channel at this point is about 500 yards wide. Swimming to the steep rocks of the island opposite, the creature shot its head out of the water on to the rock, and moving its head from side to side, appeared to be taking its bearings. Then fold after fold of its body came to the surface. Towards the tail it appeared serrated, like the cutting edge of a saw, with something moving flail-like at the extreme end. The movements were like those of a crocodile. Around the head appeared a sort of mane, which drifted round the body like kelp.”

Kemp estimated the animal was over 60 feet long. Although it was indistinct with distance — it was at least 1200 feet away, maybe 1500 — this was no fleeting sighting. According to Kemp, they watched the monster for several minutes before it slid off the rocks and swam away.

What was it? It sounds to me like a group of sea lions among the distant kelp, viewed at too great a distance and remembered with too great a dollop of imagination. But the interesting question is, “Whose imagination?”

Kemp’s description gives a clue. Despite copycat sightings describing literal “sea serpents,” and despite the serpentine image of Cadborosaurus now popular among cryptozoologists, it’s striking that neither of the original eyewitness reports described serpents at all!

Langley described something like a whale; Kemp described something like a dinosaur. His monster, he said, “gave the impression that it was much more like a reptile than a serpent….”

Responding to the Kemp sighting, one letter to the editor offered an opinion that Caddy might be a sauropod dinosaur called diplodocus. This writer noted Caddy’s long neck and long tail, and called it “probable that it has legs with webbed feet with which it propels itself.”

Kemp seized on this dinosaur idea with enthusiasm, and produced an eyewitness sketch consistent with a sauropod. He agreed, “Diplodocus describes better what we saw than anything else. My first feelings on viewing the creature were of being transferred to a prehistoric period when all sorts of hideous creatures abounded.” He said the creature’s movements “were not fishlike, but rather more like the movement of a huge lizard.”

This combination of elements — a swimming sauropod dinosaur, and the notion of being transported to a prehistoric world full of terrible monsters — sounded very familiar to me. I was reminded of another sauropod, filmed swimming in a primal environment teeming with hideous creatures: Skull Island, as depicted in the blockbuster film King Kong! Comparing Kemp’s description and sketch with stills from the film, the parallels are striking.

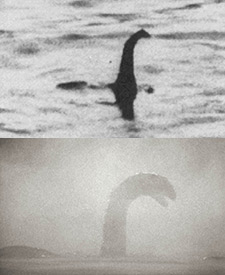

The most famous Loch Ness monster hoax photo (top) compared with a still from the film King Kong (bottom). Both images feature small models. © 1933 RKO Pictures Inc., © 2005 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Could the film have inspired Kemp’s story? The timeline certainly works: Kong, it happens, opened in Victoria just six months before Kemp and Langley created the legend of Cadborosaurus. It blew movie-goers away, scared the socks off of people, and stuck in the memories of all who saw it. (Not coincidentally, the legend of the Loch Ness Monster was likewise created immediately after the release of King Kong, and the several key Nessie sightings seem almost lifted from the film. It’s especially notable that the infamous fake “Surgeon’s Photo” looks virtually identical to a shot from the movie.)

Is this similarity between Cadborosaurus and Kong suspicious? You bet.

Kemp’s original sighting was extremely uncertain, as he admitted, because of the tremendous distance involved (well over a thousand feet). He couldn’t make out the key details. For example, the creature’s head was just a blob. It’s likely he saw a distant group of marine mammals swimming and climbing the rocks (as is entirely typical in the area), but was unable to make out what they were at that distance. Perhaps he puzzled about it for a few months before King Kong planted a seed….

When he finally met Langley, heard his sea monster story, and compared notes, Kemp’s memories were a year old, and very probably contaminated by Hollywood.

That’s a recipe for a legend — but as scientific data, it’s a disaster.

Where does this leave Cadborosaurus? As so often in the paranormal world, it seems that the entire legendary edifice, all the sightings that followed, the books and TV programs and place in pop culture, all rests on a foundation of smoke.

Smoke, and the flickering screen of a cinema.

cite this page (below is in Chicago style)

This article was published on January 1, 2008.