Today, August 18, marks the 100th anniversary of the adoption of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, guaranteeing women the right to vote. We honor that momentous event with an excerpt adapted from the chapter on women’s rights in Dr. Michael Shermer’s 2015 book The Moral Arc: How Science and Reason Lead Humanity Toward Truth, Justice, and Freedom (New York: Henry Holt).

Read the essay below, or listen to it being read by the author, Michael Shermer:

On August 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment of the United States Constitution was ratified, legally securing the franchise to women. It was the culmination of a 72-year battle that began when Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott organized the 1848 Seneca Falls conference, after attending the World Anti-slavery Convention in London in 1840 — a meeting at which they had come to participate as delegates, but at which they were not allowed to speak and were made to sit like obedient children in a curtained-off area. This did not sit well with Stanton and Mott. Conventions were held throughout the 1850s but were interrupted by the American Civil War, which secured the franchise in 1870 — not for women, of course, but for black men (though they were gradually disenfranchised by poll taxes, legal loopholes, literacy tests, threats and intimidation). This didn’t sit well either and only served to energize the likes of Matilda Joslyn Gage, Susan B. Anthony, Ida B. Wells, Carrie Chapman Catt, Doris Stevens, and countless others who campaigned unremittingly against the political slavery of women.

Things began to heat up when the great American suffragist Alice Paul (arrestingly portrayed by Hilary Swank in the 2004 film Iron Jawed Angels) returned from a lengthy sojourn in England. She had learned much during her time there through her active participation in the British suffrage movement and from the more radical and militant British suffragists, including the courageous political activist Emmeline Pankhurst, characterized as “the very edge of that weapon of willpower by which British women freed themselves from being classed with children and idiots in the matter of exercising the franchise.”1

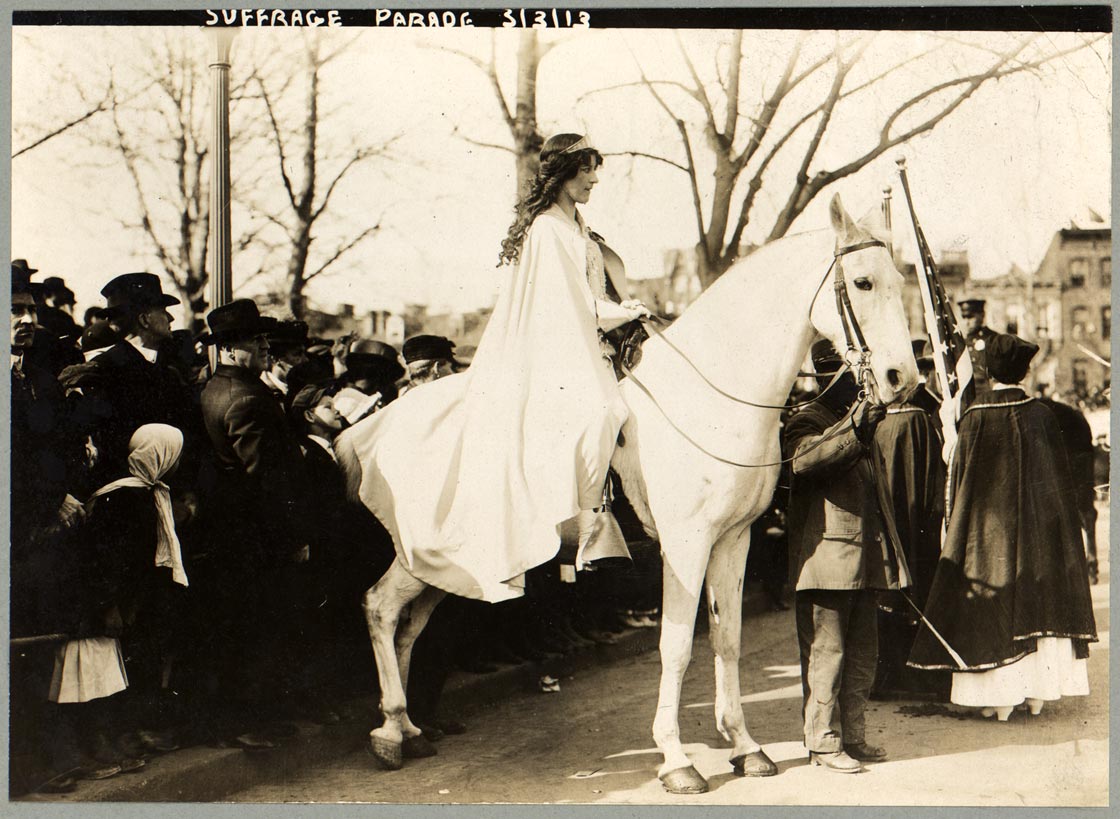

Upon her death Pankhurst was heralded by the New York Times as “the most remarkable political and social agitator of the early part of the twentieth century and the supreme protagonist of the campaign for the electoral enfranchisement of women”;2 years later, Time magazine voted her one of the 100 most important people of the century. Thus, when Alice Paul returned from abroad she was ready for action, though the more conservative members of the women’s movement weren’t quite ready for Alice. Nevertheless, in order to attract attention to the cause she and Lucy Burns organized the largest parade ever held in Washington. On March 3, 1913 (strategically timed for the day before President Wilson’s inauguration), 26 floats, 10 bands, and 8,000 women marched, led by the stunning Inez Milholland wearing a flowing white cape and riding a white horse. (See Figure 1 above.) Upwards of 100,000 spectators watched the parade but the mostly male crowd became increasingly unruly and the women were spat upon, taunted, harassed and attacked while the police stood by. Afraid of an all-out riot, the War Department called in the cavalry to contain the escalating violence and chaos.3

It was a gift. A scandal ensued due to the rough treatment of the women and suddenly, “the issue of suffrage — long thought dead by many politicians — was vividly alive in front page headlines in newspapers across the country.… Paul had accomplished her goal — to make woman suffrage a major political issue.”5

In 1917 women began peacefully picketing outside the White House but, once again, they were met with harassment and violence. These Silent Sentinels (as they were called) stood day and night (except Sundays) with their banners for two and a half years but, after the U.S. joined in the war, patience ran thin as it was seen as improper to picket a wartime president. The picketers were charged with obstructing traffic and were thrown — often quite literally thrown — into prison cells where they were treated like criminals, rather than political protesters, and were kept in appalling conditions. Many of the women went on a hunger strike, including Alice Paul, who was viciously force-fed in order to keep her from becoming a martyr for the cause.

Word of the brutality in the workhouse was leaked to the press and the public became increasingly incensed at the protestors’ horrific treatment. During what became known as the Night of Terror, 40 prison guards went on a rampage and the women were “grabbed, dragged, beaten, kicked, and choked”; Lucy Burns had her wrists cuffed and chained above her head to the cell door; another woman was taken to the men’s section and told “they could do what they pleased with her”; another woman was knocked unconscious, still another had a heart attack.6 These outrages were a grave tactical error. “With public pressure mounting as a result of press coverage, the government felt the need to act.… Arrests didn’t stop these protesters; neither did jail terms, psychopathic wards, force-feeding, or violent attacks. Their next decision was simply to let them out.”7

At long last, in 1920, the 19th amendment (originally drafted by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1878) was passed — by a single vote — thanks to 24-year-old Harry T. Burn, a Tennessee legislator who had originally intended to vote against his state ratifying the amendment (which needed ratification of 36 of the 48 states to pass), but changed his mind because of a note from his mother.

Dear Son:

Hurrah, and vote for suffrage! Don’t keep them in doubt. I notice some of the speeches against. They were bitter. I have been watching to see how you stood, but have not noticed anything yet.

Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt put the “rat” in ratification.

Your Mother.8

In the end, then, suffrage for women came down to the vote of one man, influenced by his mom. It was rumored that, “the anti-suffragists were so angry at his decision that they chased him from the chamber, forced him to climb out a window of the Capitol and inch along a ledge to safety.”9 Thus suffrage arrived in the U.S., kicking and screaming.

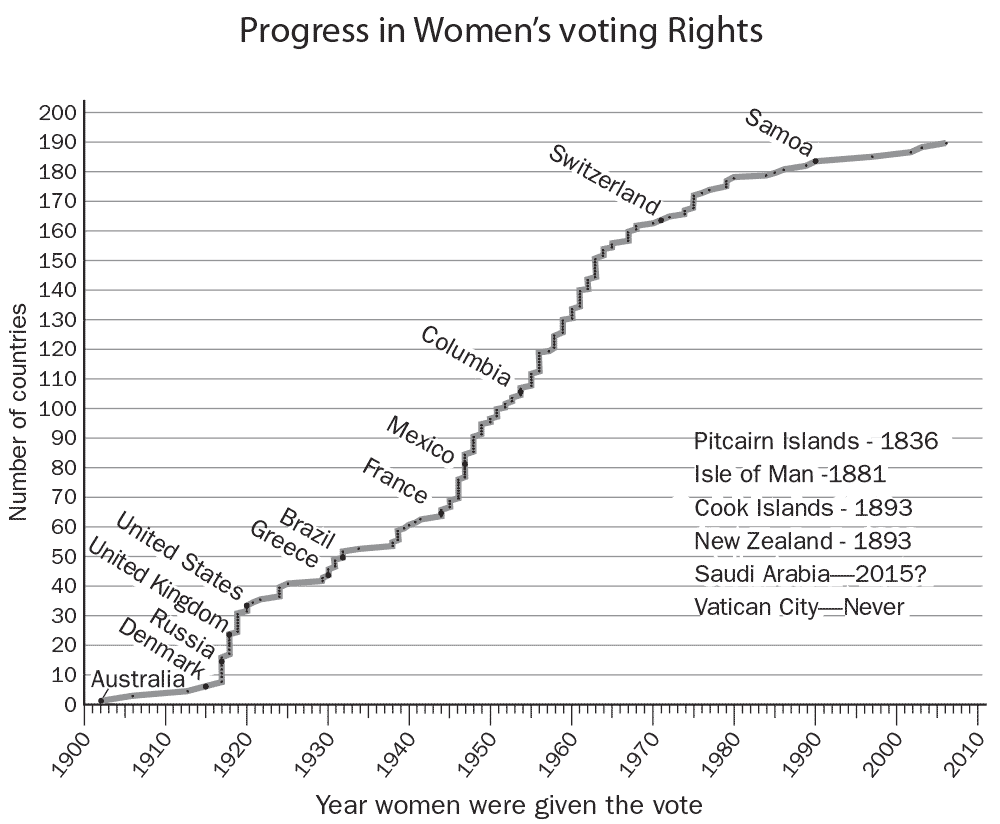

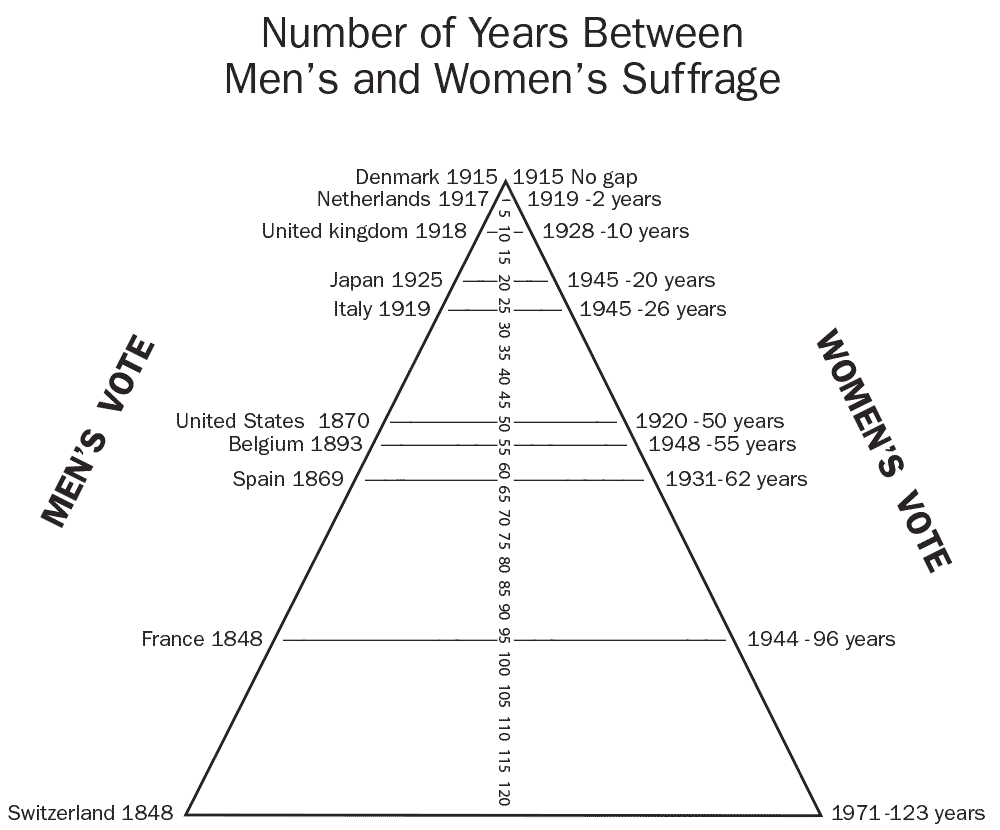

It was a right that women in a number of other countries had already won years before, but one that others would have to wait for. Figure 2 (below) tracks the moral progress of women’s suffrage, while Figure 3 (below) tracks the gaps between when all men versus all women were granted the franchise, from Switzerland’s 123-year gap between 1848 and 1971, to Denmark’s 0-year gap in 1915. By comparison, the 50-year gap in the United States between 1870 and 1920 lies mid-way in this history.

Figure 2: Women’s Right to Vote Over Time The stair-step progress of women’s suffrage is tracked over time from 1900 to 2010, showing two big bursts, the first after World War I and the second after World War II. Tellingly, the expected date for the sovereign nation of Vatican City to grant women the right to vote is “never.”10

Figure 3: The Gap Between the Franchise for Men and Women. The spasmodic nature of moral progress is reflected in the shrinking time in years between the dates that men’s suffrage and women’s suffrage was legalized, from 123 years for Switzerland to 0 years for Denmark. Such change is contingent on many social and political variables that differ from country to country.

Carving Women’s Rights: A Personal Story

The trend over the past several centuries has been to grant women the same rights and privileges as those of men. Political, economic, and social advances, enabled by scientific, technological, and medical discoveries and inventions have increasingly provided women not only greater amounts of reproductive autonomy and control, but have also driven an expansion of their rights and opportunities in all areas of life, leading to healthier and happier societies across the globe. As with the other rights revolutions there is much progress that remains to be realized, but the momentum now is such that the expansion of women’s rights should continue unabated into the future.

In these ways — the rational justification for including women as full rights-bearing persons no less deserving than men, the interchangeability of women’s perspectives with that of men, the scientific understanding of the nature of human sexuality and reproduction, and the continuous thinking that enables us to see and comprehend the difference between a woman’s and a fetus’s rights — science and reason have led humanity closer to truth, justice, and freedom.

As an example of how far we’ve come in just the last two generations (and how oppressed women were as recently as the early 20th century), I close with the story of two women — mother and daughter — both named Christine Roselyn Mutchler. The mother was born in Germany and passed through Ellis Island in 1893 with her parents, who then moved to Alhambra, California. Mother Christine married her husband Frederick and gave birth to baby Christine in 1910 (and a second daughter three years later), but their lives were shattered shortly after that when Fred told his wife he was going out for a loaf of bread and never returned. Abandoned by her husband, left with no money or food to care for herself and her two small children, mother Christine was forced to return to her father’s home.

Unknown to her at the time, Fred had wandered off into the county jail with delusions that his father-in-law was after him. After being examined by a physician he was sent to a mental hospital for over a year. During this time, with his delusions in remission, Fred wrote heartbreaking letters to his wife asking about her and the children, but Christine’s father kept the letters from her and she continued to believe that she had been abandoned. In time she found work as a housemaid for a friend of a successful motion picture executive named John C. Epping, whose wife had recently died. Desperate for a daughter and enamored by three-year old Christine, Epping talked Christine’s father into forcing her to allow him to adopt the child. Young, poor, scared, and intimidated by her father, Christine reluctantly agreed to the adoption, although a series of articles in The Los Angeles Times show that a probation officer on the case opposed the adoption, declaring “she believed Epping saw possibilities of a future Mary Pickford in the little girl, and that the child should have a home in some private family where home life and education would be the principal features.”11 Based on the false information provided by Christine’s father that Fred had abandoned them, the judge granted the adoption.

Epping promptly changed the name of his newly adopted daughter to Frances Dorothy Epping, addressed her by her middle name, and (unbelievably) told her she was born in Providence, Rhode Island and that his deceased wife was her true mother. Now age four, Christine/Dorothy apparently did not accept the fictional story and rebelled — or perhaps Epping changed his mind about raising a daughter as a single Dad — because he shuffled her around through a series of surrogate parents, including sisters at the Ramona Convent in Alhambra and caretakers at the Marlborough Preparatory School in Los Angeles, before shipping her back east for a year to live with his sister in the Catskills, and then on to Germany where she lived with Epping’s relations. During that period Dorothy discovered that she had a talent for the arts, in particular sculpture.

She then returned to Los Angeles and finished her secondary education, after which she was reunited with her original family and told the truth about the adoption. She went on to college at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C. and the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, Germany in the 1930s under the tutelage of Joseph Wackerle who, at that time, was the Third Reich Culture Senator and received praise from both Goebbels and Hitler. (She later recalled being stunned by the hypnotic pull Hitler had on an audience of one of his speech’s she attended.) In the meantime, Dorothy’s real mother, Christine, was instructed by her father to divorce her husband Fred, after which she met and married a vegetable cart vendor in Los Angeles, left her father’s oppressive rule, and began to rebuild her life and new family. But the tragedy of being forced to give up her first-born child haunted her the rest of her life. As the world changed and Christine saw how women became more empowered in the second half of the 20th century, she continually asked herself why she didn’t speak up and oppose the adoption.

Meanwhile, as Dorothy came of age she soon discovered that family law and the adoption courts were not the only worlds ruled by men. Her chosen profession of sculpture was a heavily male dominated one, so to be taken seriously she began using a truncated version of her first name Frances — Franc — and that gained her entrée into the German academy and subsequent galleries and museums (even now one can find references to “his” work). She later recalled that when the professors at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich found out “Franc” was a women, she had to listen to lectures from the hallways because only men were allowed inside. From the early 1930s through her death in 1983 — by which time it was acceptable for women to shape clay, wood, and stone with their hands — Franc Epping’s work was shown in numerous exhibits throughout the United States, including the prestigious Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. One of her works, “The Man with a Hat,” even appeared in an episode of the original series of Star Trek. I know because I own that piece, along with many other sculptures of hers, which I inherited from my mother.

Franc Epping’s work, “The Man with a Hat,” appeared in an episode of the original series of Star Trek (The Original Series, Season 1, Dp. 24 A Taste of Armageddon, at 17 minutes, 25 seconds). That sculpture, along with many other Epping sculptures, were inherited by Michael Shermer from his mother. Franc Epping was the author’s Aunt.

You see, Franc Epping was my Aunt, her real mother Christine was my grandmother, and I am proud to be related to such a resilient and determined woman.12 Aunt Franc’s sculptures portray strong women with muscular features in empowering poses — allegories for what women for generations have had to rise to in order to gain the recognition and equality that is rightfully theirs. This book was written in the inspiring presence of those carved stones. ![]()

Figure 4: Sculptor Franc Epping, born Christine Roselyn Mutchler and given the adopted name Frances Dorothy Epping, started using the masculinized version of her adopted name — Franc — in order to be taken seriously in the male-dominated world of sculpture.

Figure 5: Among Franc Epping’s many sculptures are strong women with muscular features in empowering poses.13

About the Author

Dr. Michael Shermer is the Founding Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of the Science Salon Podcast, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University where he teaches Skepticism 101. For 18 years he was a monthly columnist for Scientific American. He is the author of New York Times bestsellers Why People Believe Weird Things and The Believing Brain, Why Darwin Matters, The Science of Good and Evil, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His new book is Giving the Devil His Due: Reflections of a Scientific Humanist.

References

- Purvis, June. 2002. Emmeline Pankhurst: A Biography. London: Routledge. 354.

- Ibid., 354.

- Stevens, Doris. Edited by Carol O’Hare. Originally published 1920; 3 revised and edited 1995. Jailed for Freedom: American Women Win the Vote. Troutdale: New Sage Press. 18–19.

- Source: Library of Congress. George Grantham Bain Collection. Original caption reads: Inez Milholland Boissevain, wearing white cape, seated on white horse at the National American Woman Suffrage Association parade, March 3, 1913, Washington, D.C. LC-DIG-ppmsc-00031 (digital file from original photograph) LC-USZ62-77359 http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/97510669/

- Ibid., 19.

- Adams, Katherine H. and Michael L. Keene. 2007. Alice Paul and the American Suffrage Campaign. Illinois: University of Illinois Press. 206–208.

- Ibid., 211.

- http://www.tennessee.gov/tsla/exhibits/suffrage/beginning.htm

- Ibid.

- The Wikipedia entry for “Women’s Suffrage” has a complete list of every country and when they legalized the franchise for women: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women%27s_suffrage

- “4-Sided Battle in Court for Child.” 1914. Los Angeles Times, October 31.

- Most of this story has been carefully documented by Ann Marie Batesole, a private detective and my cousin — our grandmother was Christine, Aunt Fanci’s mother.

- Source: Author’s collection.

This article was published on August 18, 2020.

Nice to see Australia at the front of the women’s suffrage graph but I think our New Zealand cousins would point out they got there first in 1893. Though Australia was also early in letting women stand for Federal Parliament in 1902.

Great, informative and thoughtful essay. If you want to see the visual history check out the PBS American Experience series on the subject. Really dramatic, especially the final vote for ratification at Nashville. Truly heroic, dedicated women facing unbelievable odds including physical abuse and jail.

Alice Paul is my heroine.

Hugh