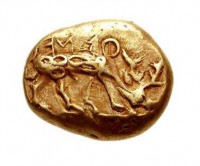

Coins entered the world of ancient Greece by the 6th century BCE, shortly followed by the first material philosophers. (Image by Classical Numismatic Group, Inc., via Wikimedia Commons, used under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.)

Precisely when the guttural croaks and screeching hoots of ancient humans became words is a mystery. We do know language can be measured in hundreds of thousands, if not millions of years—that is, humans have been physiologically capable of sharing observations about their surroundings for a long time. For most of history, the stories we shared have described a universe that is personal, emotional, and whimsical.

Then, about two and a half thousand years ago, something different happened. On the coast of modern day Turkey in a city called Miletus, a man named Thales wondered what everything in nature was made of. His answer was almost mundane: water.

It’s unlikely Thales of Miletus was the first to consider this question, nor the first to suggest an answer. Since none of his writings have survived the ages we are forced to rely on writers like Aristotle and Herodotus to speculate on the thoughts of this so-called ‘first philosopher’. But Thales represented the emergence of a way of thinking new in human history, where the universe emerges from a single system of impersonal qualities.

The demarcation problem makes it impossible to define the boundaries of science, yet it undoubtedly comprises a complex variety of behaviours such as measuring, discussing, modelling and predicting. Crucially, science involves seeing the universe as if it’s governed by unchanging rules rather than personal intentions. These rules are symmetrical in time and space, existing independently of the desires of some supernatural force.

This simple concept opened the way for groups of people to openly hypothesise on the fundamental nature of everything, on properties such as change, time, and matter. The question is, why did it take so long for humans to consider this?

Biologically, the brain in Thales’ head was little different to those in the skulls of ancestors dating back tens of thousands of years. At least, not different enough to account for a sudden spark of insight. To gain some understanding of why humans started to think about the universe in terms of rules rather than supernatural intentions so recently in our past, it pays to ask what impedes us from thinking of a rule based universe, and then look at what was significant about the Turkish coast in the 6th century BCE.

The Tribal Brain

Comprising of tissues and cells and an array of organic chemicals, subject to variation under the control of genes, the chunk of meat called a brain is little different to any other organ in the living world. Its ability to give rise to a mind is a neat trick, but biologically it holds no privileged position as an accident of evolution.

It doesn’t seem unreasonable to think a brain would help create mental models of reality to solve problems. After all, the human species has spread across the globe—and beyond—thanks to this feature. Yet the features of our remarkable intelligence, reflected in our ability to use language, temporal reasoning, and creativity, appear to have more to do with understanding other people than understanding nature.

There are a number of hypotheses explaining human intelligence, but perhaps one of the more compelling arguments focusses on social interactions as an evolutionary pressure. Proposed by British anthropologist Robin Dunbar—he of the famous ‘Dunbar’s number’—the social brain hypothesis suggests larger collectives facilitated an advantage in more complex communication, and an ability to empathise or predict the intentions of competitors within a social hierarchy.

The tools we use to mentally model the behaviour of other people can easily be applied to non-humans. Indeed, most religions imbue objects and environments in our surroundings with human-like intention and sentiment, described as animism among less structured religious cultures.

It’s arguable whether religious thinking has itself offered an evolutionary advantage, but it’s clear its place in our history hasn’t been detrimental enough to seriously compromise the advantage of having a social brain. Indeed, it’s possible that the perception of being allied with non-human features of the universe has particular social advantages. Nobody would want to piss off the guy who is best friends with thunder and lightning, for example.

There’s no reason to suspect this innate bias prevented any individual from speculating on non-animistic systems of nature. But for any such speculation to develop beyond some fleeting flight of fancy, it would require a number of conditions. One would be for the thought to develop into a structured model. Another would be for it to be shared among peers, horizontally across the social group or vertically down through time.

Theoretical models rarely (if ever) spring fully formed into human consciousness. Even in modern science, scientists tend to evolve existing models to explain new phenomena, relying on a similar idea as a metaphor for an otherwise inchoate theory. A complex, teleological model of nature has a ready made analogy in our social brain, unlike a monistic, rule-based one. What’s more, sharing such a radically new model with peers means risking vital social bonds with a personal universe.

The Ionian coast in the 6th century BCE was a far cry from our ancestral tribal lifestyle. By then, diverse human social groups were associating in civilisations fed by an industry of agriculture, where oral tradition had been replaced with written works and the universe could be mapped and measured using complex number systems. This brave new world wasn’t exactly novel to ancient Greece, however. So what was so novel that Thales and friends could revolutionise human thinking forever?

A Melting Pot of Ideas

Many things could conceivably pressure new systems of thinking. Being forced to consider alternative belief systems, for example, could evolve new cultures. Miletus and its surrounds was indeed a multicultural melting pot.

There are two problems with this pathway. For one thing, mixing with different cultures wasn’t new. Phoenicia had been trading with the far reaches of the Mediterranean, journeying as far as the British isles for centuries prior to Greece becoming a maritime power. For another, there seems to be a greater tendency for people to polarise their beliefs when encountering alternative systems, reinforcing ‘us and them’ rather than creating completely new models of thinking.

Another entirely plausible possibility is the development of a new form of government—democracy. Phoenicia concentrated wealth and power, funneling their resources up through a hierarchy into a monarchy. As such, it benefits individuals to subscribe to a central way of thinking and provides limited opportunity to consider new models of nature.

Yet within a democracy, opportunity for a redistribution of wealth exists. Risks can be taken to change allegiances, and more freedom in sharing and debating ideas exists within select social groups. Where else could you chew on a crazy concept except in a democracy?

As appealing as this hypothesis might be, it struggles for lack of strong evidence. The pre-Socratic, materialist philosophers that include the likes of Thales and big names such as Anaximander, Heraclitus, Parmenides, and Zeno weren’t known for favouring rhetoric quite in the same way as their philosophical descendants. If democracy presented a way to criticise old authorities in favour of new ones, the value didn’t seem to be reflected in the pre-Socratic tradition.

Nonetheless, the kindling could well be laid by factors of cultural diversity and democratic freedoms. The spark could have come in the form of one other novelty: the coin.

A Penny for Your Thoughts

As a token of exchange or recording transactions, money has been around a long time—a lot longer than 2500 years. But in a modern sense, the coin represents a lot more than a token of value.

According to historian Professor Richard Seaforth, the nature of the coinage developed in Ionia around the 6th century BCE implied something different to the more ancient exchanges of tokens or of bartering. Emerging from an existing system of redistribution of wealth from sacrificial offerings, it developed into the first true system of communal faith in a value. It was the first time society was monetised.

The consequences of this development aren’t difficult to imagine. For one thing, as with democracy, individuals can take greater risks with the established values of liquid wealth than they can with the personally subjective values of bartered goods. Society becomes more fluid, so to speak. Yet according to Seaforth, the very concept of money also provided a model for thinking differently.

“The universe is no longer imagined as controlled by a monarch but by what may seem to be an all-powerful, all pervasive impersonal substance, and the first and only such substance in history is money,” says Richard.

Coins provided a metaphorical scaffold for considering an economics of nature; one that—like money—was consistent and agreed upon. There was still a role for animism and mythology, one which persisted through the poetic treatises of many pre-Socratics such as Parmenides. But this notion of nature being grounded within a single, impersonal structure seeded a radical new way of looking at the universe.

Looking around at our technologically advanced modern world, it’s easy to take the culture of science for granted. It seems so obvious in hindsight! Why did it take us hundreds of thousands of years to come up with it? The appeal in the coin hypothesis for the generation of material philosophy—and from that, the long road we eventually think of as science—is that it provides a cultural stepping stone from one social behaviour to another.

Very interesting! We follow with awe the Greek beginning in mathematics and science and today I learned another important factor in the birth of rationality. Thanks!