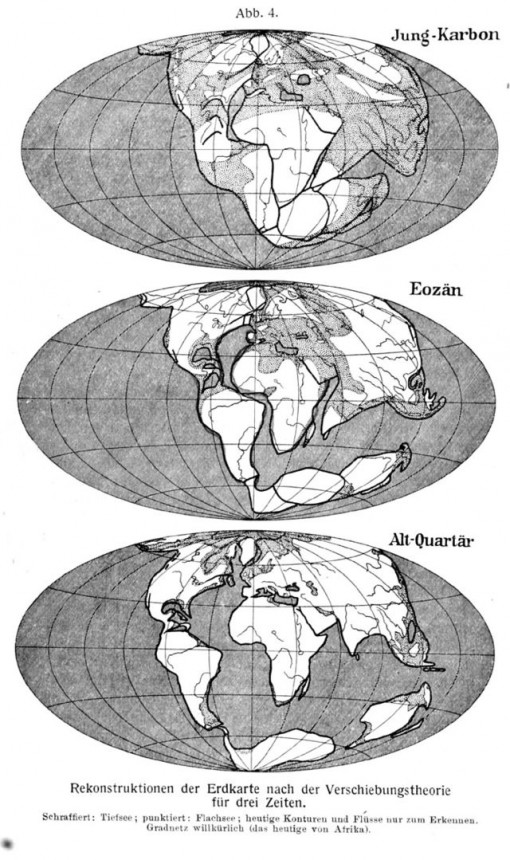

Alfred Wegener’s 1915 reconstruction of the drifting of the continents from a supercontinent of Pangea to today. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons).

Every year of the 20th century included many scientific breakthroughs and achievements, but few years were as important as the year 1915—one hundred years ago this year. It seems odd that it stands out as such a watershed. World War I had broken out the previous August with the rapid German advance through the Low Countries and northern France and almost to Paris, then been beaten back by an Allied counteroffensive. By the beginning of 1915 the Allied and Axis lines across Belgium and northern France were deeply entrenched, and they would barely budge for three more long years of pointless slaughter. Yet despite these horrific events, science marched on. In physics, Einstein published his theory of general relativity, which gave us the concepts of space-time and warped space. His theory also successfully explained the peculiarities in the apparent motions of Mercury. (However, the paper was not widely read for a while because of wartime restrictions on circulating scientific publications). Ada Hitchins established the first radioactive decay series, showing that radium was a decay product of uranium. Pluto was photographed for the first time, although not yet recognized as a planet. Thomas Hunt Morgan demonstrated non-inherited genetic mutations in fruit flies, undermining the foundation of eugenics. The Nobel Prize in Physics went to the Braggs for their development of X-ray crystallography, which became important not only in geology but also was the key to unlocking the structure of the DNA molecule and many other scientific discoveries.

But 1915 was truly revolutionary in the geological sciences. Not only did that year see the publication of some of the first radiometric dates establishing that the earth was many billions of years old, but perhaps the most important scientific achievement of all: the publication of Alfred Wegener’s Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane (The Origin of Continents and Oceans). This work was the beginning of a true scientific revolution that transformed geology right down to its core, although the final stage of the revolution was not completed until the 1950s and 1960s. And like many revolutionary works, it was ahead of its time, and widely scorned and rejected by those who were in scientific power.

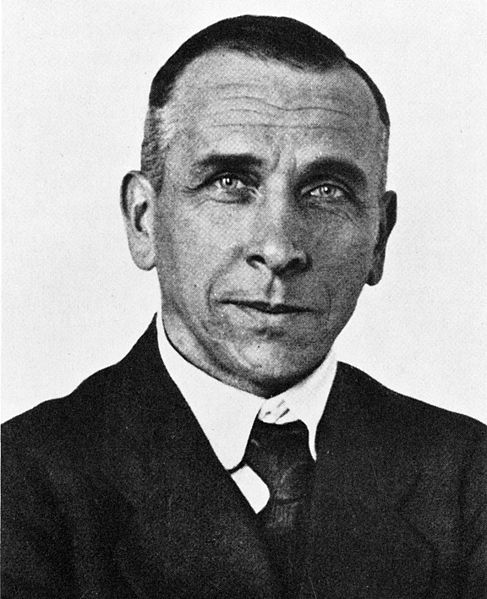

Wegener was an unlikely revolutionary for the geological sciences. Born in Berlin in 1880, he was the son of a clergyman, not a scientist. He initially studied Classics before switching to astronomy, meteorology and climatology, but never had much formal training in geology. By 1905 he was working at an meteorological observatory, and in 1906 he organized and led the first of four expeditions to Greenland to understand climate in polar regions. He was an instructor in meteorology at the University of Marburg by 1908, where he worked with the legendary climatologist Wladimir Köppen (whose climate classification scheme is still used today, as I taught my Meteorology class last semester), and in 1913 married Köppen’s daughter. That same year he ran his second Greenland expedition and spent the winter on the ice, and nearly starved to death before he and his companion were rescued.

When war broke out in 1914, he was drafted, as was nearly every able-bodied young man in Germany at the time. After being wounded twice (once in the neck) in the infantry at the start of the war, the German High Command decided he was unfit to be trench fodder. They sent him to the army weather service, where he traveled between weather stations all over Axis-held Europe. Despite all this traveling and army work, he managed to finish writing his book (which he had started in 1912) while he was serving in the army, and it was published late in 1915. The book had little impact because of the wartime restrictions, but Wegener published another 20 papers in meteorology and climatology before the war ended.

After the war, he obtained a position at the German Naval Observatory in Hamburg, then at the University of Hamburg, and finally accepted a secure post at the University of Graz. During this time, he wrote an an influential book with his father-in-law on the climates of the geological past. But his ideas about drifting continents were not widely read or accepted yet, especially not in the geological community in Europe and the U.S. In 1926, he presented his ideas at the meeting of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists in New York City, where he was rejected by everyone except the chairman who had invited him. His ideas continued to be scorned by geologists, but Wegener was still working hard, gathering data in Greenland in 1929. In 1930, he led his fourth and last big expedition to Greenland, the largest he had ever mounted, with propeller-driven ice sleds and much innovative equipment. In November 1930, he and a partner were returning from a supply run to their remote camp in the center of the Greenland ice sheet when they ran out of food and got into bad weather. Wegener died at age 50, and was buried on the Greenland ice sheet, where his body still rests today under many feet of ice. He never lived to see any support for his revolutionary ideas, which would not come for another 25 years.

Wegener’s book was a masterful compilation of all the evidence available at the time. Since the first decent maps of the Atlantic Ocean in the 1500s, people had speculated whether Africa and South America fit together, but Wegener showed the fit also included India, Madagascar, Australia and Antarctica as well. As a climatologist, he was particularly impressed by the way certain deposits are strongly controlled by climate and latitude: ice caps on the poles, rain forests on the tropics, and desert deposits in the mid-latitude high-pressure belt between 10° and 40° north and south of the equator. But when you went back to the Permian Period (250–300 m.y. ago), those deposits made no sense on a modern globe. The south polar ice sheets extended from South America and Africa and apparently stretched across the equator to India, which is a climatological absurdity. Only if you put the continents back into their Permian configuration as part of a single supercontinent, Pangea (“all lands”), did they make sense. If the continents had not moved, then the bedrock scratches that ran from Permian glaciers in Africa and matched those in South America would require the glacier to jump into the Atlantic, flow in a straight line from Africa to Brazil, and then jump out of the ocean! Likewise, all the ancient Permian desert deposits and coal swamps of tropical Permian rain forests only made sense if they were put back in their Pangea locations, not their modern latitudes. Even the ancient Precambrian bedrock in South America and Africa matched precisely like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Clinching all this was the evidence from the Permian fossils. There were distinctive extinct seed ferns known as Glossopteris found on all the continents of the southern landmass known as Gondwana. There were small reptiles like Mesosaurus, found in lake beds in Brazil and South Africa, and protomammals like the bulldog-sized beaked herbivore Lystrosaurus and the bear-like predator Cynognathus, that could never have swum across the modern Atlantic Ocean. To Wegener (and to the modern geologist), this evidence should have been clear and conclusive: the continents drift apart like the ice floes Wegener knew so well.

If the evidence was so solid, why was he despised and rejected? Why did geologists treat his ideas as fringe, and call him a crackpot for another 45 years after his book was published?

If the evidence was so solid, why was he despised and rejected? Why did geologists treat his ideas as fringe, and call him a crackpot for another 45 years after his book was published? Part of it had nothing to do with evidence, and everything to do with the sociology of science. First of all, Wegener was not a formally-trained geologist, and there is natural reluctance to accept ideas from outside your community that appear to violate your basic assumptions, such as the fixity of continents. I myself have blogged about a number of amateurs who propose crackpot ideas, like the expanding earth or crazy notions about the earth’s magnetic field, clearly ignorant of geology and unable to see why their ideas have been rejected based on good evidence. Even more importantly, Wegener’s evidence came mostly from the Southern Hemisphere, yet almost all the world’s geologists back then lived in Europe or North America, and relatively few had ever traveled to South Africa or Brazil. Naturally, the evidence is much more persuasive if you can see it in person, rather than read it in type and crummy black-and-white photos that were normal for journals back then. Indeed, Wegener’s biggest boosters, such as South African geologist Alexander du Toit, were mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, and could see the evidence firsthand. Another supporter was British geologist Arthur Holmes, known as the “Father of the Geological Timescale” for his pioneering work in radiometric dating in 1913–1915. He embraced Wegener’s ideas—but then he had worked as a geologist in Africa before returning to England. Holmes boldly published diagrams showing drifting continents and mantle convection for the first time in his widely used geology textbooks in the 1920s, 40 years before the geological community came to accept the notion.

But it was not all due to sociology. Wegener had no mechanism to explain how continents drifted, and the ideas he proposed (such as centrifugal force) weren’t very plausible. Geologists argued that if the continents had plowed across the ocean basins, there should be huge areas of oceanic crust crumpled up on their leading edges like the snow on a snowplow blade—and such deposits did not exist. Meanwhile, they dismissed the matches in rocks across the continents as inconclusive, and concocted fantastic land bridges to explain how animals could have gotten across the Atlantic Ocean. They continued to denigrate Wegener and hold his ideas up for ridicule for decades. In 1949, the leading American paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson had published numerous papers arguing that the fossils did not require continental drift. His institution, the American Museum of Natural History, held a big symposium dismissing all the evidence of moving continents (published in 1952).

Ironically, as this heap of scorn reached its acme, evidence was coming from an unexpected direction: the bottom of the ocean. Both Wegener and his critics were totally ignorant of what the oceanic crust was really like, and the answers did not come until after World War II, when modern marine geology was born. By the late 1940s and 1950s, several oceanographic institutes had vessels routinely criss-crossing the world’s oceans, getting detailed surveys of seafloor depth, seismic reflection profiles of seafloor structure, gravity and magnetic profiles, and routinely collecting sediment cores everywhere they went. By the late 1950s, we had our first real glimpse of what 70% of the earth’s surface actually looked like, thanks to the detailed seafloor maps by Marie Tharp and Bruce Heezen. Meanwhile, paleomagnetic data gathered on land showed that the continents had moved with respect to the poles, and established the flip-flops of the earth’s magnetic field, which allowed the final nail in the coffin: the proof of seafloor spreading by Fred Vine and Drummond Matthews in 1963. It turned out that Wegener’s critics were wrong: the continents do drift around the globe, but they don’t crumple up the oceanic crust ahead of them because most of it is subducted beneath the plates.

I feel fortunate in having lived to witness this scientific revolution. It began about the time I was born, and when I was an undergraduate in 1972–1976, geology instruction around the country was just beginning to make the transition from old ideas to plate tectonics. In graduate school at Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory and Columbia University, I was taught by many of the pioneers of plate tectonics: Neil Opdyke, who developed magnetic stratigraphy in ocean cores; Lynn Sykes, who confirmed plate tectonics through seismology; Bill Ryan, pioneer of marine geology who helped discover that the Mediterranean was a desert 6 m.y. ago; Walter Pitman, who figured out the complex pattern of magnetic stripes on the Pacific sea floor; Wally Broecker, who coined the term “global warming” and was a giant in both oceanography and climate change; Jim Hays, who helped discover the causes of the Ice Ages; and Bruce Heezen and Marie Tharp, who single-handedly mapped the entire ocean floor. They were the generation that pushed the scientific revolution to its conclusion. But it all began a century ago with Wegener.

Part of it had nothing to do with evidence, and everything to do with the sociology of science. First of all, Wegener was not a formally-trained geologist, and there is natural reluctance to accept ideas from outside your community that appear to violate your basic assumptions, such as the fixity of continents.

A more recent example of this tendency is the reluctance of paleontologists to accept the hypothesis that an asteroid collision was responsible for the extinction of the dinosaurs because it was proposed by a physicist, Nobel Laureate Luis Alvarez.

Actually, it was more complex than that. The evidence was discovered by a geologist, Walter Alvarez (Luis’ son), whom I knew before he was famous. And the reluctance was not just professional inertia, but also the fact that the end-Cretaceous was a complex time, with the Deccan volcanics (2nd largest in earth history) erupting before and during the extinction. In addition, there was a complex pattern of land extinctions and marine extinctions that don’t match the “asteroid did it all” hypothesis very well. Today, the momentum has shifted, and most geologists and paleontologists agree that it was a complex extinction with multiple causes. The simplistic “asteroid did it all” model has been rejected based on evidence, not based on sociology. See my chapters on the topic in my books “After the Dinosaurs” (Chapter 2) and “Greenhouse of the Dinosaurs”.

I really appreciate the article. I’d like to add another name – J. Tujo Wilson – who along with Alfred Wegener & Harry Hammond Hess I have included on my poster which I entitled “The Pieces of the Evolution Puzzle”. And I’d also like to add that nothing in geology makes any sense except in the light of plate tectonics.

“It seems in the name of consistency we ought to either condemn the geologists or cut the Christians some slack.”

I do not recall reading that Wegener had to recant his hypothesis, was forbidden to publish or was threatened with torture. He was also able to continue with research, did not have to endure house arrest and had to call himself lucky to escape with his life and not experiencing Brunos punishment. He also did not have to endure imprisonment while on any trial.

I really resent your accommodationist nonsense comparing the actions of an utterly vile and inhumane institution that is infested with crime with the workings of scientistsand their organizations. You in doing this are as vile as the institution you are seemingly trying to defend in some misplaced sense of balance.

Great stuff! Really enjoyed the article and the comments. As a Christian I can’t help but note the similarity of the treatment of Alfred Wegener by the geologic community and the treatment of Galileo by the church establishment of his day. The treatment of Galileo is hung like an albatross around the neck of the Christian community but the treatment of Wegener is just acknowledged as history without corporate guilt being heaped onto modern geologists. It seems in the name of consistency we ought to either condemn the geologists or cut the Christians some slack.

Nice article and complemented by useful comments/corrections. I am glad Dr. Prothero came with this instead of going about the still open theory of catastrophic anthropogenic global warming. There is at least another interesting unproven theory about the Earth, concerning the origin of oil. Thomas Gould, of important scientific accomplishments, has it explained in “The deep hot biosphere”.

The proponents of mysterious land bridges couldn’t show any evidence for that hypothesis either, and they were wrong. Many of this group who rejected Wegener’s hypothesis pretty well dismissed it out of hand, which is not good science either. A good review of this issue for the non-scientist (like me) is the book “Four Revolutions in the Earth Sciences” by James Lawrence Powell. These four revolutions were : (i) Deep time, (ii) Continental Drift and Plate Tectonics, (iii) Meteorite Impact and (iv) Global Warming. According to the book’s author, the early rejection of each of these hypotheses followed a similar pattern to the pattern referred to here. In the end, the sciences needed to more fully investigate these hypotheses were developed and settled the main elements of these ‘revolutions’. In my opinion, ‘Good science’ involves includes putting forward an hypotheses that challenges the status quo (hopefully with some evidence that shows the possibility of being correct) and letting the evidence decide.

“Part of it had nothing to do with evidence” – and part of it had everything to do with evidence.

The maps show one problem: Wegener claimed the continents move a lot faster (two orders of magnitude) than they do. When scientists repeated his measurements they found nothing, since their equipment wasn’t precise enough.

Other problems are described in the article. All in all, his hypothesis wasn’t much better than the hypothesis of many bridges. The honest scientific standpoint would be that the issue was unsolved.

Of course, many people believed that the continents had moved, but very far ago, until the crust solidified. That would explain e.g. the African/South American symmetry. Wegener’s idea was that the continents are still moving.

Wegener’s reputation as a geological Galileo is, on the whole, unfounded. He was right but couldn’t show it, which doesn’t qualify as good science.

You seem to dismiss the paleontological evidence and the paleo-climatological evidence that supported his hypothesis, as well as geological evidence.

Your argument “He was right but couldn’t show it, which doesn’t qualify as good science”

seems to not take that evidence into account.

“Wegener’s assessment sticks out for two reasons. The first reason Wegener’s hypothesis holds weight is that Wegener used geological evidence to back his claim that Africa and South America were at one time connected. The collection of maps, rock formations, and fossil records provided the evidence Wegener needed to connect South America to Africa.”

“Next, Wegener used geologic and fossil records to further support his claim. Wegener noticed that fossils from a small lizard from the Paleozoic Era (approx. 270 million years ago) appeared in only two places on Earth. Fossils for the Mesosaurus are found only in southern Africa and eastern South America. The Mesosaurus was a freshwater animal and would be incapable of crossing the Atlantic Ocean. This would lend credence to the belief that Africa and South America were connected 270 million years ago when the Mesosaurus roamed the Earth.”

“1.) Alfred Wegener observed the apparent wandering of earth’s magnetic pole. Wegener attributed this to the movement of the

poles followed the approximate path of the movement of his continents. Not only did this discovery provide evidence of continental drift, it also was an early example of the study of paleomagnetism.”

“2.) Wegener also used paleo climatology to help prove his theories. He used fossil records to study climate change through geologic time. Paleoclimatology is currently a hot field in science, as scientists attempt to determine the potential effects of greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activity.”

https://www.e-education.psu.edu/earth520/content/l2_p10.html

I think your assessment is way out to lunch.

I see you mention Alex du Toit. I mapped an area in 1970 for my Masters Thesis previously mapped by Alex du Toit in 1905. (reference: du Toit A.L., 1905, Geological survey of Glen Gray and parts of Queenstown and Wodehouse. Tenth Annual Rept., Cape Geological Commission). His work was done before the Cape Colony became part the Union of South Africa in 1910. My point is that despite his study being a regional one, the quality of his maps was outstanding. The information I have is that he did most of this work on his own. His book “The Geology of South Africa” first published in 1926 but with a number of subsequent editions is a masterpiece.

Dear Mr. Prothero,

some corrections to this otherwise excellent article: Wegener didn’t lead the 1906-1908 and 1912-1913 expeditions – the leaders were Mylius-Erichsen and Johan P. Koch, respectively. Though Wegener was co-organizer of the Koch expedition, both it and the Mylius-Erichsen expedition were under Danish flag.

The third photo shows him on the 1912-1913 expedition, not the 1930 one, which becomes evident if you compare it to the previous photo of 1924, showing a much older Wegener supposedly 6 years prior.

And a nit to pick: In the sentence

“That same year he ran his second Greenland expedition and spent the winter on the ice, and nearly starved to death before he and his companion were rescued.”

it should read “companions” since they were four people on that trip.

Source: Wegener, A., Tagebuch eines Abenteuers. Eberhard Brockhaus, Wiesbaden 1961.

Yours in peer,

Robert Seidel.

A nit to pick: The Axis powers were WWII, not WWI. The side opposite the Allies in WWI is properly referred to as The Central Powers

Alfred Wegener – one of my earth science heroes… thanks, Dr. Prothero.

I grew up in Germany, but I remember in high school in the mid sixties we already talked about Wegener and continental drift as an explanation why the continents fit together.

Maybe pride of “ownership” needed after the hammering in WW2?

Two major early advocates for seafloor spreading as a mechanism for continental drift were Harry Hess at Princeton University and Robert S. Dietz at the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey (and later at Arizona State University).

Dietz later moved from marine geology to the study of meteorite impacts. At ASU he was the first campus advisor for the Phoenix Skeptics and was an outspoken critic of creationism. After his death in 1995, the Robert S. Dietz Memorial Lectures were established at ASU; in 2006 the Dietz Memorial lecture was given by Eugenie Scott of the National Center for Science Education.