The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs, by Robert T. Bakker, illustrated by Luis V. Rey (New York: Golden Books, 2013); 64 pages; reviewed by Daniel Loxton.

This review also appears in the current January–February 2015 issue of the Reports of the National Center for Science Education (Vol. 35, No. 1). See the table of contents, or download a PDF copy of this article here.

The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs, by Robert T Bakker, illustrated by Luis V Rey

I’ve always loved books about prehistoric animals. Nothing brings back the glow and wonder of childhood like opening my dog-eared, loose-paged copies of Golden Books’ 1977 Dinosaurs, with its old-school tail-dragging creatures painted by legendary fantasy artists Tim and Greg Hildebrandt, or Happytime Books’ 1979 Dinosaurs, lovingly illustrated by Bernard Herbert Robinson—and lovingly inscribed “This book belongs to Danny” on the frontispiece. I spent more happy hours with those books than I could possibly tell you, curled up on my grandma’s couch. Did it matter that the animals were often inaccurate even by the standards of the time, or sometimes mislabeled altogether? Did I love such books less for presenting the whole of the geologic past as a jumbled Lost World where Jurassic Stegosaurus might have challenged Cretaceous T. rex, or perhaps even have grazed beside mammoths? Of course not—but with better books I might have loved these vanished creatures in deeper, truer ways.

Science and children’s nonfiction have both come a long way since then. And yet, in some ways you’d hardly know it from the dinosaur books you see in your local bookstore. As a father of young children, and as a children’s dinosaur writer and paleoartist myself, I’m honestly a bit horrified by the ceaseless churn of low-end, low-brow dinosaur schlock. (It’s a particular pet peeve to see the exact same cheap, off-the-shelf commercial computer- generated dinosaurs on the face-out covers of multiple books in the same aisle at the same time.)

The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs is a nostalgic re-imagining of another kids’ dinosaur classic, Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Reptiles: A Giant Golden Book (1960). It’s a pleasure to say that it is a stronger offering in many ways than either the naive books of my youth or the shallow commercial clutter on modern store shelves. Written by paleontologist and author Robert T. Bakker, and illustrated by paleoartist Luis V. Rey, The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs is more ambitious than its title suggests. Dinosaurs and their relatives and contemporaries are the focus, but this is no mere collection of dinosaur factoids. Every page of this book aims to provide context, placing dinosaur discoveries within a history of scientific sleuthing, and the prehistoric animals themselves within a geologic and evolutionary history. The first seven spreads are devoted to helping us understand that dinosaurs “were just one part of a great family tree of animals with backbones” and “not even close” to being the first prehistoric giants. Readers are taken on brisk tours of the Devonian, Carboniferous, Permian, and Triassic periods and introduced to the lineages that predated and led to the rise of the dinosaurs. “Whenever we want to unlock the mysteries of who is related to whom, we go back to the skull holes” (page 20), Bakker writes, describing how skull fenestrae distinguish archosaurs from other diapsid reptiles.

As Carl Sagan once said, “There is a danger of underestimating the intelligence of kids. Kids can understand some pretty deep things.”

If this sounds a bit challenging for the “3–7 years” age group recommended by Golden Books’ parent publisher Random House Children’s Books, I have to agree that it is. Having written for that age group myself (Tales of Prehistoric Life), my sense is that The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs is better suited for older kids of perhaps 7–10 years of age.

All the same, as Carl Sagan once said, “There is a danger of underestimating the intelligence of kids. Kids can understand some pretty deep things.” Bakker clearly agrees. He offers young readers a chance to reflect on many weighty ideas—change over time, branching lineages, evolutionary arms races, contingency, and sexual selection among them—and weaves those into an accessible, energetic text. He seeks kid-friendly language (“veggie-saurs,” “furball,” or much less helpfully, “dactyl” or “pterodactyl” as folksy but inaccurate synonyms for “pterosaur”). He crafts colorful flourishes (“Fwump. Crrrunch. Yum”), clear descriptions (“kept their ankles high off the ground like ballet dancers”), and crisp explanations. Parents will appreciate the species pronunciation guide, which also functions as an index.

The book’s evolutionary emphasis is a real point of strength. Various forms of the word “evolve” occur more than twenty times in the book’s fifty-two pages of primary content. This should come as little surprise. Bakker has argued elsewhere that “We dino-scientists have a great responsibility” to champion that evolutionary perspective because “our subject matter attracts kids better than any other, except rocket-science.”

Bakker has been described as “controversial” and “an iconoclastic figure,” but writing nonfiction for young readers is by its nature a conservative enterprise.

I enjoyed this book, but it is not without problems. Bakker has been described as “controversial” and “an iconoclastic figure,” but writing nonfiction for young readers is by its nature a conservative enterprise. Reading through, I found myself thinking that speculations, unconfirmed likelihoods, or Bakker’s preferred sides of scientific controversies were sometimes matter-of-factly presented as though they represented a firmly established consensus. Similarly, Bakker downplays ideas of which he’s less fond. For example, he gives as much space (four lines) to an idiosyncratic hypothesis that the non-avian dinosaurs were annihilated by disease as he does to discussion of the asteroid impact hypothesis. While he discusses the strengths of the former, he mentions only weaknesses of the latter—and neglects to make any mention whatsoever of the fact that, whatever its role in extinction, a very large impact is known from physical evidence to have indeed taken place.

Bakker’s long-time collaborator Luis Rey is something of a radical himself. His unusual, intensely colorful approach to paleoart has been described as “a style not to everyone’s taste” or even “divisive.” Rey works in a loose, impressionistic photomontage style that combines digital painting, photographs, and models. Though I, like Rey, come out of acrylic painting and now do most of my work on computers, I find his current work difficult to embrace. This is largely a matter of personal taste (his unapologetically patchwork approach diverges philosophically from the seamless effect I aspire to in my own computer-generated dinosaur art), but there are artistic decisions in this book which I find distractingly weird. For example, animals and elements are frequently cut-and-paste duplicated in the same poses in the same picture. The extensive use of off-the-shelf, digital faux-paint filters in backgrounds and elsewhere is sometimes baffling, as when The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs processes several pictures of fossil-hunter Mary Anning to somewhat resemble paintings—including one Anning portrait which already was a famous painting!

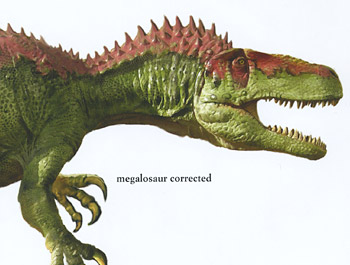

“Megalosaur corrected” llustration detail from The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs

Nonetheless, there’s much to like about Rey’s contributions to this book. His anatomy appears accurate and up-to-date. This is as rare as hens’ teeth in children’s dinosaur products. The impressionistic style forthrightly emphasizes the artist’s hand, aesthetic intuitions, and speculations in reconstructing these animals—a kind of honesty that can be lost in images that look photographic but are not. Some pictures, such as his “megalosaur corrected,” are downright beautiful. Also, critically, the book’s art passes the eight-year-old test. My young consultant praised the dynamism of the pictures, and particularly admired some color choices that seemed far too psychedelic for my own tastes. Well, so be it. I’m not the book’s intended audience.

In the end, I have mixed feelings about The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs. I feel that it calls for a certain amount of caution, but I long to recommend it for its energy, and the depth of its ideas, and the poetry of its storytelling. Kids could do much worse than to dig into a book that so eloquently describes the place of the dinosaurs in the broader tapestry of animal life and geologic time—a book which reminds us that “the dinosaur story is really our story, too.”

I had, among other things, the _little_ golden book, as described at http://chasmosaurs.blogspot.com.au/2013/05/vintage-dinosaur-art-dinosaurs-little.html (possibly a later edition).