This post is the third and final in a series I began more than a year ago. The first post discussed how rationality differs from intelligence, how both may be measured, and what may keep intelligent people from behaving rationally. The second describes three of the four broad categories of factors involved in rational thinking while taking a closer look at how one thinking disposition, the need for cognition, affects decision-making and problem solving. I highly recommend reading the first two posts before continuing with this one as the background is important.

In summary, we tend to the think that people are irrational because they lack intelligence or knowledge. Both may contribute to rationality. However, intelligence and education are no guarantees of rationality because other factors such as cognitive laziness and open/closed-mindedness are just as, if not more, important. In other words, human beings tend to be irrational out of stupidity or ignorance, but also out of laziness or arrogance.

The scientific process addresses each of these factors to ensure that the answers we find are as accurate as possible. Although the scientific method itself is inherently intelligent, a good researcher must have a minimum level of intelligence in order to succeed as good research rises above bad through the process of peer review. Scientists conduct very thorough reviews of literature to produce theoretically sound hypotheses (addressing ignorance). Regarding cognitive laziness, science itself is curious; scientists would not be in the business if they were not intellectually curious and willing to do the work to find accurate answers. Finally, science is competitive and interactive, discouraging arrogance. An individual scientist may be overconfident, but the process of peer review and replication beats that arrogance down in order to produce a consensus view.

The more open-minded and flexible one is, the more rational one will be.

Science, in theory at least, is rational. People, in general, are not. Of course that’s why we need science. Unfortunately, we don’t spend our lives evaluating every choice and every belief using scientific study, so we need to be more cognizant of the things that get in the way of everyday rationality if we want to lead more productive lives.

Stanovich and West (covered in the Stanovich book cited below) have shown us that one of the most important qualities that consistently rational people demonstrate is a flexibility in thinking, and open-mindedness. Good rationality requires us to consider alternatives to the way we currently think the world is. It requires us to set our current beliefs aside long enough to objectively evaluate other views. The more open-minded and flexible one is, the more rational one will be. Hubris and narcissism often prevent intelligent people from doing this consistently, which in turn prevents rational thinking.

Overconfidence can put you in hot water a number of ways. Take our example (discussed in Part I) of Paul Frampton, the accomplished physics professor who fell for a “honey trap” and was arrested for drug smuggling in Buenos Aries. Frampton begged the police to read his text messages, sure that they would exonerate him by showing that the bag that he was transporting was not his own. However, the messages also demonstrated clearly that Frampton knew that the bag contained cocaine and that he chose to transport it anyway. Frampton believed that he was innocent and that the person he had been exchanging text messages with for weeks was a bikini model 35 years his junior who loved him. He was so sure that his judgement was correct that he could not imagine how the situation might look from someone else’s point of view. It should be no surprise that two psychologists testified that Frampton had traits of narcissistic personality disorder. Frampton’s downfall was overconfidence.

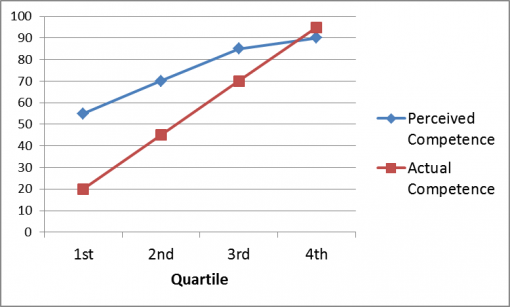

Being overconfident in some situations can put your life in danger, but the most damage is probably done through everyday choices and behaviors which chip away at our quality of life. The Dunning-Kruger Effect is a phenomenon that many skeptics might be aware of, namely it is an inverse correlation of competence and overconfidence. The people who are the least competent in a given domain tend to overestimate their competence the most.

The vast majority of people overestimate their competence in any given domain due to a set of biases we use to protect our self-esteem. For example, almost everyone rates themselves as above average in most ways. In the case of judging competency in an area such as reading comprehension, those who score in the lowest quartile (below the 25th percentile) tend to rate themselves above the 50th percentile. Those who rank just below average tend to rank themselves a little bit higher at, say, the 70th percentile, and so on. The more competence one has, the less they overestimate. The most competent people actually tend to underestimate.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect: the less competent one is, the more one over-estimates one’s competence.

Dunning and Kruger attribute this effect to knowledge. In other words, the more we know, the more we understand how much we do not know. Conversely, those with the least competence don’t know what they don’t know.

At this point you might be wondering what this has to do with rationality. Well, when overconfidence is combined with inflexibility, rationality is nearly impossible and the potential damage is boundless. Stubborn overconfidence is arrogance and arrogance is blinding.

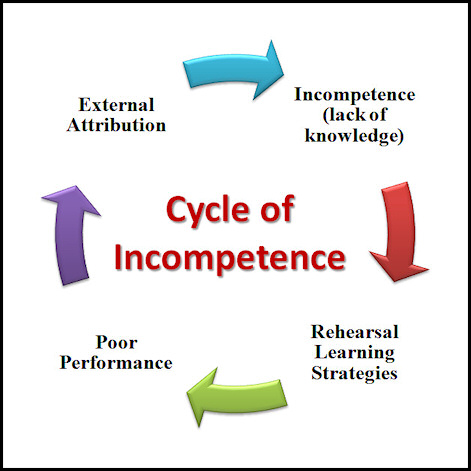

A few years ago a student and I noticed a correlation between entitlement attitudes, study habits, and academic performance. We hypothesized that students who used poor study strategies (e.g., rote memorization or “rehearsal” of conceptual material) felt entitled to do so and resisted the conclusion that poor grades were a result of those strategies. We conducted a study to test that hypothesis and learned that students with high entitlement attitudes were the most overconfident, were the least competent (this is the Dunning-Kruger Effect), and tended to attribute academic performance to forces outside of their control (the teacher, the system). These students also tended to use poor study strategies such as flashcards and memorizing bullets on lecture slides.

This creates what I call a “Cycle of Incompetence.”

Students perform poorly because they don’t understand the material and they don’t know that they don’t understand it. They reject feedback (such as low grades) as related to their study habits because they attribute performance to outside forces. Feedback therefore does not cause them to change their behavior. This is correlated with feelings of entitlement, superiority, and narcissism, so they feel entitled to continue with poor study strategies (and receive high grades), so they do. Those poor strategies do not lead to greater competence, hence they remain in a cycle of ignorance and incompetence.

If you think that you are competent or right, if you don’t know that you don’t know and you won’t accept criticism as feedback, it’s unlikely that you will make the changes needed to become competent.

This problem affects more than learning. It is a factor in everything from voting to interpersonal relationships to deciding which peanut butter to buy. When we are unable to set aside our beliefs and opinions, unable to accept the possibility that those beliefs are wrong, we are unable to objectively evaluate arguments and evidence. When we are unable to be objective, we are unable to be rational. And when we are unable to be rational, we risk forming beliefs and making choices which do not lead us to our goals.

Open-mindedness, humility, and flexibility are cornerstones of rationality. Science—the best means of acquiring knowledge—is humble, open, and flexible for that reason. You may be reasonably certain of a conclusion, but the moment you close the door on the possibility that you are wrong, you become irrational.

So being smart is not enough. Being smart and educated is not enough. We must be smart, educated, curious, and open-minded, and this last one is perhaps the most important of them all.

References

For those looking for more to read on this subject, I highly recommend the following books. They are all written by respected researchers and cover the literature in relevant fields:

- Stanovich, K. E. (2010). What Intelligence Tests Miss: The Psychology of Rational Thought. Yale University Press

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Ariely, D. (2009). Predictably Irrational. Harper

- Tavris, C. & Aronson, E. (2007). Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me): Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Twenge, J. M. & Campbell, W. K. (2008). The Narcissim Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement. Atria Books

Did you enjoy this post? Read the previous two installments in this three-part series, “Why Smart People Are Not Always Rational” and “More On Why Smart People Are Not Always Rational.”

Good read, but a question.

You spoke of several reasons for irrational thinking. How does addiction or addictive behavior fit into irrational decisions for most people?

Being open minded and aware that the more we know, the more there is to know, how do we reach an actionable conclusion on a topic. At what point do we get to apply the heuristic (pardon my ignorance but I can’t recall whether to credit Randi, Martin Gardner or …) that we should strive to keep as open a mind as possible, but not so open that our brains fall out.

Re: Mensa, I have an amusing anecdote:

I was invited by a Mensa group in the Sacramento area to give a talk on my book “Secret Origins of the Bible,” which is about the mythic origins of much of the biblical text. My talk was in the afternoon. At the evening banquet a scientist gave a talk on the extraterrestrial origin of the basic molecules of life, i.e. that they were delivered to the primordial earth, along with water, by comet and asteroid strikes.

After the meal, an excited young Mensa member came up to me and said that, hearing my talk in the afternoon and hearing the dinner speaker’s talk about the extraterrestrial origin of the building blocks of life that, “. . . this book is true!” He held up a book by “Rael,” founder of a flying saucer cult that claims benevolent space aliens called the Elohim (the intensive / plural of “El,” the Hebrew word for “God”) created life on earth 250,000 years ago, that life didn’t evolve.

The young Mensa member’s filter for interpreting information to fit his beliefs was obviously quite sophisticated.

Regarding ancient UFOs, back in 1968, when I first read Erich von Daniken’s book, “Chariots of the Gods?” I was impressed by what seemed a massive amount of evidence. I was much more credulous back then in my feckless youth. Fortunately, I was only reading a library copy. I was equally fortunate to read Timothy Ferris’ “Playboy” interview of von Daniken, in which Ferris confronted von Daniken with multiple examples of the man’s lies.

This, I think, highlights another possible source of rational breakdown: We are, to some degree, programmed toward credulity and an assumption that most people we deal with will be truthful. I was fortunate not to have had my youthful credulity overly victimized by con artists trying to directly take my money. For all that, bitter experience can be a cure.

Thank you Ms. Drescher for a very informative series of articles. Here’s a question: You say that “Open-mindedness, humility, and flexibility are cornerstones of rationality.” Very few people are introspective enough to admit they lack the aforementioned qualities. Do you know a narcissist who is aware of it? And pretty much everyone thinks they are humble, flexible, and open-minded. (With the exception of Clarence Thomas, the Supreme Court justice who stated “I ain’t changing”)

Is this irrational?

Colin Powell uses the 40%/70% rule of thumb for making tough decisions. Tough decisions gone wrong could unnecessaryly increase the death toll. He says you can make the tough call on as little as 40% good intel – he calls it a gut decision – any thing less and, he says, you’re shooting from the hip. By the time you have more than 70% good intel, it’s likely too late to do anything.

The notion is that intuition is what separates the great leaders from the average ones, by recognizing and accepting that during a battle, certainty is not possible, so trust your gut.

Do you know off hand the odds for Powell knowing that aluminum irrigation tubing, travelling to farming areas of Iran, was just for farm irrigation use?

If the Universe came with an instruction manual, it would come with the product at delivery, therefore it would be found in the CMB data.

Yet the CMB data is being delivered at all times, in the form of polarized light, coincidentally perhaps quantum entangled, as would be the case with any possible long-distance intelligence communication scheme.

Giving muse to that one has managed to live ONCE, discounts all theories espousing ‘never to have existed”. This too would bolster credence to the scenario of living more than one time.

In this manner, the intelligent can be misinterpreted as lazy, when really they are in no hurry for credentials nor rushed advancement of a regimented enquiry process.

This provides MORE PROOF of my thesis that 99.99999999% of the population IS IGNORANT, STUPID, ILLITERATE and MENTALLY SICK!!!

Now I’ll wait for all the STUPID replies.

I would sure like to read that paper if you have it available.

Two comments (hopefully I won’t be charged extra):

1) I suspect cognitive laziness may be the greatest problem our society is faced with. But where does the notion of short cuts or cognitive simplifications come in? In many areas we use simplifying assumptions to streamline investigations and decision-making. If every investigation began with the re-derivation of every tool/principal/formulation used nothing would ever get done. So we use assumptions, trust previous research, and experience, to progress. If something goes awry laziness is blamed when often it is simply trusting simplifying assumptions that were wrong or misapplied, or experience that was poorly understood. Perhaps the respondents in the liver survey were in fact splitting the difference since they were skeptical of the simplifying assumption baked into the survival probabilities, and allocating 50% to the probability assumption, and 50% to other-assumptions-not-presented. I would be interested in understanding how rational thinking uses assumptions to shortcut or streamline thinking without erring on the side of laziness. Perhaps this is a distinction without a difference.

2) What is this about flashcards being a poor study tool? I use them all the time. Maybe you have helped explain why I am having trouble learning Spanish!

Excellent discussions, for which thank you. Seems to me that “effective” and “effective behavior” could nicely stand in for the terms “rational” and “rationality”. The word “rational” by itself has only to do with logic and reason, not to do with fact, while “effective” brings real-world fact into the picture. One can have a crazy counter-factual goal yet be utterly rational in pursuit of it, and vice-versa. Most laws – No Child Left Behind, for example – have practical or noble goals, but many if not most laws are ineffective in leading to achievement of their stated goals. Other laws – Prohibition, for example – have unachievable goals yet might still have highly rational approaches to enforcement.

About prohibitions in general, what may seem like “highly rational approaches to enforcement” may seem that way because we are persuaded by the arguments of the “Baptists” when those making the arguments may actually be the “Bootleggers”

Most irrationality is caused at least in part by cultural factors, religion being the best-known example. A person raised in a religious system may be unable to think rationally about topics that that system has strong convictions about, regardless of how intelligent he may be on other subjects.

This applies to scientific convictions too. Most scientists have blind spots because their scientific training includes far too much slavish respect for scientific superstars and their alleged accomplishments and not enough willingness to disrespect the established thinking. One example is that anyone who disagrees with the Darwinian Hypothesis on how biodiversity came about is automatically regarded as a Christian Fundamentalist and given no chance to present any of the several alternative, scientific, non-religious, non-Darwinian explanations for evolution.

Wow. I thought the relentless peer review within the scientific community was, well, pretty relentless in trying to disprove any new hypothesis that come their way. Perhaps you have a study that show otherwise?

I would recommend reading Dan Airely’s research. Part of the problem is that educational institutions do not encourage students to be good crap detectors; that is one of the reasons ponzi schemes keep on attracting a new generation of suckers (some have been caught more than once!)

The other problem is the notion that my opinion is as good your opinion; this basically devalues rational discourse if a person’s opinion that the moon landing was an elaborate hoax is as good as my opinion that it was a genuine event then we do not even have the basis for rational discourse.

You are so right. The one that really gets my goat is when someone says “I am entitled to my own opinion. This is a free country.” That basically ends the conversation. I am often tempted to retort: “Of course, you are entitled to your own flawed opinion, but you’re not smart enough to distinguish between right and wrong.” I have that script in my head, but when confronted with an actual encounter, I shut up for the sake of peace. I’m dying to say that, for example, to a family member or an opinionated acquaintance. Yes, many “smart” people are not smart enough not to be stupid.

Right. It often sounds like, “I guess we both must agree to disagree.”

I went right to my Kindle to order Kahneman’s book. What can I conclude about the fact that there were over twenty of the “brief summary” books available? Should I just enjoy the irony?

This text is the best birthday gift I could get. It made me rethink and analyse again a lot of things about the world in general and me myself as well. It’s a kind of (I don’t know whether it’s a proper word) reminder for me, that I should at least try to be more humble, less lazy and not fall into this horrible intelectual stagnation. Thank you again.

Thank you Barbara – a truly insightful set of articles. I had recently started to doubt open-mindedness because judgements, i.e. closing certain doors, I believed, help us learn, advance and hence reach our goals quicker (cognitive lazyness, if you will). Your argument has taken me back from those beliefs which I think was necessary.

I am wondering though, whether emotions don’t play a bigger role. You mention narcissism, for example, but isn’t that in the end an emotional connection? Similarly, regarding the children example in your second article, wouldn’t it be that a group as a whole triggers a more emotional process, whereas a numerical list breaking down the chance of survival partly prevents this trigger and allows for more rational decision making?

While more rationally minded people don’t have to be less emotional, I believe they are able to exercise a higher level of control of said emotions, at least initially, which then enables a more objective perspective, but please correct me if I’m wrong.

Barbara,

Excellent set of articles…

Thanks for posting these three articles, I have just read them at one sitting. At the moment I am working on helping take Carol Dweck’s ideas about Growth Mindset to the business world. Carol simplifies her top line message (I think) and appears to focus only on ‘intelligence’ however when looking under the covers at the detail, her finding are pretty much aligned with the case you make. However what she hasn’t done is call out ‘rationality’ explicitly. So, your argument has allowed me to organise my thinking and make sense of her position, this is not trivial, I have been on this for about 50 hours, so far. (so a big thank you, again)