We’re all intuitive dualists. It certainly seems that the world consists of two realms: the ordinary physical world of space and time and stuff; and the literally metaphysical (that is, beyond physical) world of the mind. Although this was undoubtedly everyone’s sense of things since the beginning of time, it’s now primarily associated with René Descartes, who articulated it in the 17th century, so it’s now known as Cartesian dualism. This immaterial realm is home to all metaphysical entities and forces (actually existing or not): the mind, soul, and spirit (whether or not these terms are synonymous); ghosts; God and the angels; Satan, devils, and demons; fairies, elves, and spirits; and fate, luck, destiny, and karma. Animals (according to Descartes) are purely physical beings, lacking both mind and soul, while people have both material bodies and immaterial minds.

Since the Age of Reason, however, secular, monistic materialism has become the dominant stance, in which reality (the world, the universe) consists of only one realm: the physical. (At least for the purposes of doing science. Some scientists who claim a belief in God assert that such belief isn’t incompatible with the principles of science.) Organisms, including human beings, are part of the physical world and biology is, at least in principle, reducible to biochemistry and ultimately to physics. In fact, as the science of psychology developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the mind was banished, at first only methodologically (because introspection proved an unreliable and highly suspect foundation for a science) but in time philosophically as well. Remarkably, the science of psychology (etymologically, the science or study of the psyche—the mind) was redefined as behaviorism— the science of behavior only! Even today, in academia, behavioral science (or the behavioral sciences) is essentially synonymous with psychology.

Science, apparently, requires denying or at least ignoring the mind. Even if excluded as a subject matter, mind is central to a science. It’s impossible to explain science without mentalistic vocabulary: science develops theories to explain interesting (perhaps even puzzling or perplexing) observations. Doing science requires making decisions and judgments, justifying and defending ideas, and examining and evaluating the work of others. (It has been argued that quantum physics reintroduces mind to physical reality because the collapse of quantum uncertainty occurs only when an observer—presumably one with a mind— makes an observation. This seems unlikely. Did the universe, like the forest with the falling tree without anyone to hear, get by for almost fourteen billion years without suffering any quantum collapses because there were no physicists to observe them? And does a quantum system in a state of uncertainty know that the interfering photon is there to take a measurement and not just stopping by because it was in the neighborhood?)

Behaviorism was never an entirely comfortable stance. For all the trouble that philosophers, academic psychologists, and other scientists have with mind, we ordinarily accept its reality. Reports of pain and other sensory dysfunction are central to the diagnosis and treatment of injury, disability, and disease; hallucination, dreaming, and optical illusions are studied scientifically; and pain and pleasure are understood as real. (If not, faking an orgasm would hardly be possible.)

With the science of neurophysiology came a near-universal understanding that the mind is the result of activities in the brain. But mind itself continues to be a mystery—judging by the number of books, articles, journals, websites, societies, and YouTube videos attempting to explain it. Some philosophers (and cognitive scientists, an interesting phrase in this context) simply dismiss consciousness as just (!) an illusion. This is, of course, hijacking the word illusion, leading as it does to some paradoxical notions, such as the illusion of an optical illusion. And even granting that consciousness is an illusion, the illusion is still occurring—how? Where? To what or whom?

Nonetheless, science proceeded for about 300 years in a not uncomfortably materialistic stance. Dualism had, apparently, been eradicated. Then, starting around the middle of the 20th century, a new kind of dualism arose that’s still with us today. This modern version of dualism introduces a new metaphysical realm that might be called the computational or the cybernetic. This realm embraces not the computers themselves—which are mere physical entities (like the poor animals)—but rather the programs running on them. These programs escape the material world by manipulating something entirely ethereal—information. (Or data—in the computational realm, the two words are interchangeable.)

The foundations for the modern computer were most notably laid down by Alan Turing, Alonzo Church, Claude Shannon, and John von Neumann. The fundamental idea is of a general purpose symbolic processor. (Such a device is now called a Turing Machine.) In this context, symbol doesn’t mean what it does in ordinary discourse—something endowed with significance or meaning, such as a fertility symbol, a sex symbol, a religious symbol, or a patriotic symbol. Here, symbol means an arbitrary sign that, by agreement, is understood to represent a particular idea or concept (its referent) and that can be mechanically manipulated using specified rules without regard to the meaning of that referent. For example, the numeral 0 is an arbitrary mark we’ve agreed represents the number we call zero. The numeral 1 is another mark, which we’ve agreed represents the number we call one.

We’re all so familiar with these symbols and how they’re used we overlook that they aren’t actually the numbers themselves but only their representations. But, for example, the arrangement of the numeral 1 followed by the numeral 0 can represent the number we call ten (in our familiar decimal number system), the number two (in the binary number system), eight (in the octal system), or sixteen (in hexadecimal). Conversely, we can represent the number ten using the numeral 1 followed by the numeral, the figure X (in Roman numerals), the letter A (in hexadecimal), and so on.”

In the physical, material world, there’s no inherent relation between a symbol and its referent—any more than that there’s a relationship between a Voodoo doll and the person it represents. The relationship is entirely a matter of social reality—our common cultural agreement. The information being processed by the computer doesn’t exist in a metaphysical realm any more than there’s an immaterial realm of football with entities like first downs and extra points. This is just as true when the numbers are represented by voltage levels in a computer as when they are represented by marks on paper or stone. That a voltage level in a computer file is carrying a bit of information is simply not an inherent physical property like charge, mass, or momentum. Like beauty, information is in the eye of the beholder.

To perform arithmetic or any other computation, we follow a set of rules that specify how to manipulate arbitrary symbols to achieve certain results. Because these rules can be followed mechanically— without any understanding of what they mean or why they’re being performed—they can be executed by a machine, such as a mechanical calculator or a computer. What’s happening in a computer is simply that a physical system in the material world is changing state. (And generating a lot of heat. As one wag suggested, a space alien visiting our planet might conclude that our computers were nothing more than heaters. The problem faced by space aliens examining our computers would be similar to that of SETI scientists: Whether an apparent signal is an actual one can be answered definitively only in the negative—by demonstrating a natural explanation for it.)

The notion of a cybernetic realm of reality separate from material reality has another metaphysical aspect: the computer program itself—not merely the information it’s understood to be processing—floats free of any physical reality, because it can be run on any computer, and so consists not in its material realization but in its ideas.

Although implicit from the very beginning of the computer era, the field of artificial intelligence (a coinage of computer scientist John McCarthy in 1956) introduced the notion that the mind wasn’t inherently a function of the brain, but simply information processing (the mathematical formula for this is brain/mind :: computer/program). In the early, heady, hubristic days of good old-fashioned artificial intelligence (GOFAI)—when the achievement of humanlevel artificial intelligence was said to be just around the corner (usually a little after, if not during the lifetimes of the people making the argument, at least their academic careers)—the position known as Strong AI held that a computer program passing the Turing Test would actually have a mind and would experience consciousness in the same way you and I do. (Interestingly, arguments for Strong AI were sometimes made by the very same people who asserted that, since there’s no way to observe consciousness directly, we don’t actually know that anyone but ourselves is really conscious. Then how could anyone tell whether a computer was?) Others (the connectionists) believed that a suitable computer simulation of the brain (implemented with artificial neural nets) would achieve liftoff. (But would it have free will?)

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 22.4

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Either way, this reintroduces a metaphysical realm beyond mere physical reality. Information— whether processed by the meat machine of the brain or the drier and far more elegant computer—resides in the realm of pure thought. (This has led at least one computer scientist to assert that the entire universe is a computer program, and another to propose that it’s likely we are living in a computer as simulations— the nerd’s version of the belief that we’re nothing more than ideas in the mind of God.)

The brain is not a computer and the mind is not a computer program. If you examine the neurons and the synapses of a living brain, you’ll find no bits—no arbitrary symbols with referents assigned by common assent. And neither the mind nor the computer program— an invention of that very mind—justifies a return to dualism. ![]()

About the Author

Peter Kassan, over the course of his long career in software, has been a programmer, a software technical writer, a manager of technical writers and programmers, and an executive at a software products company. He’s the author or coauthor of several software patents. He’s been a skeptical observer of the pursuit of artificial intelligence and other matters for some time. He’s a regular contributor to Skeptic magazine.

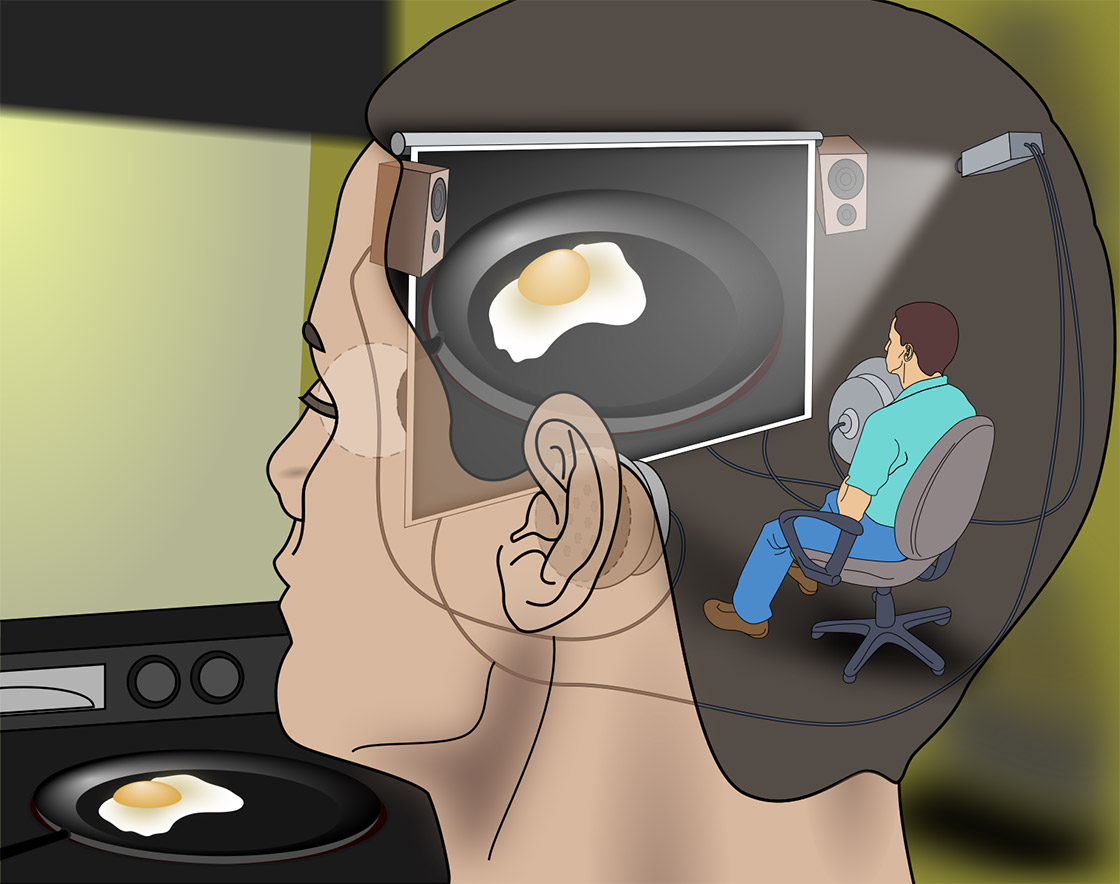

About the image at the top

An illustration of the Cartesian theater. A tiny person sits in a movie theater inside a human head, watching and hearing everything that is being experienced by the human being.

This article was published on July 9, 2018.

“Pretty sure a fly does not have consciousness”.

I have a looser definition of consciousness, I guess. I would say that even the heliotropism of a plant is a (admittedly rudimentary) form of consciousness. It’s a reaction to the environment, to enhance the probability of survival.

The distinguishing capability of humans seems to me to be the ability to record, transfer, and communicate information. That is the ability to take notes and share them with others, across space and time. No other species can do that, as far as I know, though DNA does a pretty good job of it.

The comments I’ve read so far, seems to me, miss the essential challenge in understanding consciousness. To say “The mind is what the brain does.” Falls far short. The brain of a fly does a lot that is pretty amazing, such as dodging my hand when I try to swat one, yet I’m pretty sure a fly does not have consciousness.

I describe consciousness as “knowing what it feels like to be me, and further, what it feels like to know that.” In other words, I have qualia about my own existence and qualia about that as well.

I suspect that consciousness is an emergent phenomenon stemming from self-reflective processing loops in our brains. If that’s so, will computers ever have consciousness in that sense. I don’t see why not.

I remember reading a science fiction story about a computer virus that would show up on peoples’ screens in the form of the sentence displayed, “What is my fundamental algorithm?” Turns out is was caused by a self-reflexive algorithm that went rogue, evolved consciousness in the sense I propose, and got curious about where it had come from.

Nuts on my memory, but authors L. Mlodinow & D. Chopra in their book “You are the Universe” have the similar theme and put it something like this: the beauty of the universe is in the eye of the beholder. The designer does not enter into the opinion.

Fascinating topic! I do take issue with this and related statements, and perhaps the entire thesis:

“Like beauty, information is in the eye of the beholder.”

Information, though immaterial, is absolutely real and matters as much as matter (and energy) does, and perhaps more so. For example, whatever you may think defines “you”, it is certainly not the atoms and molecules of your body, not one of which was present when “you” were born.

“The beauty of a living thing is not the atoms that go into it, but the way those atoms are put together.” — Carl Sagan

“The difference between life and non-life is a matter not of substance but of information.” — Richard Dawkins

On the whole, I thought ACW had it right in his comments. I wonder, however, at his disparagement of Descartes. Sure, he looks a little silly in retrospect, with his attempt to doubt everything and then resolve the doubt with what ACW calls a mock profundity. But we tend to forget that in taking that tack he was throwing off the shackles of centuries of authoritarian thinking, primarily Scholasticism, in favor of attempting to find an answer within ourselves. We are still trying, so “Thanks, Rene.”

If you enjoyed this article (as did I), I recommend Daniel Dennett’s From Bacteria to Bach and Back.

In the section in which the symbols for numbers was discussed, it may be wise to suggest that some of the people who contribute to the information presented in these responses do not have English as a first language. Anyone who has ever studied a second language knows that translation is not as simple as replacing a word with another. We must consider history, literature, religion, and many other things before we can truly understand what another person is saying.

The area os semantics is also important,. We write a word and expect everybody else to know exactly what we mean by it.

Artificial Intelligence apears to be a dead end. It cannot exceed its programming. At best, it is only a servant of real intelligence. We are searching space for intelligent life, but find precious little of it here. Even with all of human knowledge at our fingertips, we must still know what is useful and what should be ignored.

ACW: Good analogy using mind and movement–

…”Consciousness’ is really not that stupefying. ‘Mind’ is what ‘brain’ does, just as, for instance, ‘movement’ is what ‘muscle’ does. ..”

RH

I almost didn’t bother with this at all because it led off with Descartes. French philosophers in general are frankly junk thought; Voltaire is an exception, as is Camus and possibly also de Beauvoir and bits of Sartre. Otherwise, merde. Descartes is a bit better than, say, Foucault, who is almost entirely worthless, and not quite up to Rousseau or Diderot, who occasionally at least got off a good one. But ‘cogito, ergo sum’ is mock profundity at best; and Descartes, like most philosophers or at least most Frenchmen, needs to get over himself.

Fortunately there is more to the essay than Descartes, though alas, not much more.

‘Consciousness’ is really not that stupefying. ‘Mind’ is what ‘brain’ does, just as, for instance, ‘movement’ is what ‘muscle’ does. You don’t think of ‘running’ as a Platonic entity existing (except perhaps as a concept) separate from the limb and muscles that generate the action, do you? Of course not. So why would ‘self’ and ‘mind’ exist separately from the organ whose electrical activity and structure generate the action?

All creatures that have brains or sensory structures that respond to environmental stimuli — i.e. all living things from viruses up to the most complex multicellular organisms — have some degree of consciousness (and of free will, but let’s leave that can of worms sealed for now). H. sapiens has developed a further quirk, of self-consciousness, or awareness if you prefer; and like a male toddler who has discovered his penis, he just can’t get over himself. However, we are an experiment, if you will, in nature’s Darwinian scheme (merely a metaphor, I don’t wish to impute ‘intelligent design’ to nature, which kind of throws everything against the wall and what sticks, sticks). The collection of kludges which is ‘man, this quintessence of dust’ omits a lot of advantages other creatures have – compared to most other species, our senses are far duller, and our ‘magnificent brain’ *hah* is a sort of consolation (or booby?) prize. It remains to be seen if we can survive. I suspect the microbes, or the cockroaches, will win in the end, though, and they will mourn us only as a vanished cheap source of food.

In a vastly simplified nutshell, what we think of as “self” emerges from the unification of interactions between stored mental schematics and input from our various sensory systems. In newborns, there appears to be two dominant processing systems. One, builds neural representations of the environment wherein incoming sensory perceptions that align with genetically determined neural arrays (instincts) create early scaffolding on which concepts form. The other, is a system for identifying the source of nurture (the so called “mother/infant bond”). Without this ability to recognize the parent, life and thus the species would be short. This is an ancient program found in many organisms including most mammals and birds. Even some insects show signs of a similar but separate mechanism. As a rule this quality is out grown as an organism matures.

Humans, however, having many aspects of neotonous apes, retain this juvenile quality (as well as many others) into adulthood. The absent nurturer is now replaced with other protectors – gods, spirits of ancestors, etc. The feedback system between these two dominant neural assemblages, gives rise, once language is acquired, to the internal voice that represents, “one’s self.” In essence, the duality is not body/mind, but rather two, “minds” conversing. Of course there are many other factors far too complex to include here at work.

An interesting article, but leans to the metaphysical a bit too much for me.

Not so explicit here, but many philosophers seem to have “advanced” by replacing Earth as center of the universe with the human brain. This seems to me to be a most peculiar approach.

So many articles discuss the human brain in context of something more than a particular type of organ a tiny bit more impressive for the moment than many of billions of other animals possess on a tiny planet among many billions of other planets which that animal has named Earth. After deeming it and himself the center of the Universe, some of those human animals have moved on, some not.

I don’t believe that concept of “mind,” if that is taken to mean “brain process,” is central to reality and hard science any more than its place as the best tool that an insignificant creature of the universe has had available. But, its the best we can do, at least while we are learning how to build more powerful thinking machines.

Also, the concept of human “observation” in the quantum world has nothing to do with anything more than the fact that we humans can not know the exact state of a quantum system (or any system) until we observe it. It does not mean that event/s did not take place and states have changed, it simple means we can only guess until we see (observe/detect) a confirmation of that change.

Schroedinger’s Cat was his sarcastic example of exactly that. An example of how silly it was to claim the cat was both dead and alive until we observed it .

Be it cats or subatomic particles, we simply have no way of knowing until we somehow can confirm the state, by “observing” it directly or indirectly. The “observation” is just our necessary “peek into the box” to detect a state and remove our ignorance. In quantum cases (not cats in a box) perhaps it is a wave function our detector did in fact force it to collapse, so in that case it was our observation triggered the outcome. In that regard it would be a bit more like the opening of the box being set to either kill or not kill the cat. Other than that silly case, the cat was dead or alive completely independent of whether we ever looked into the box, and wave functions have been collapsing since billions of years before humans were around.

I do not believe there are many quantum physicists who do not understand the meaning of “observation” and that requirement in determining states in the quantum sense, or for that matter any other.

Kassan writes, “In the physical, material world, there’s no inherent relation between a symbol and its referent—any more than that there’s a relationship between a Voodoo doll and the person it represents. The relationship is entirely a matter of social reality—our common cultural agreement. ” which is true as far as it goes. But he has stopped without asking why there is common cultural agreement about the referents of words. Obviously its the folk version of epistemic philosophy. “Voodoo doll” is defined ostensively by pointing to one and giving the story about it’s supposed relation to a person. All language is ultimately grounded in shared, physical experience. It becomes mysterious when people think only of definitions in words.

…”information. (Or data—in the computational realm, the two words are interchangeable.)”

Not quite! Data are the lists of facts, observations, items etc from which connections may be made (more quickly, and often only, by a computer) and conclusions drawn, ie information. That my cactus flowered today may be an interesting fact, to me at least, whereas a record of its flowering over several years imparts useful information when allied to concurrent weather conditions and climate zone.

Perhaps physics has slightly muddled meanings by referring to signals as information in its contemplation of black holes and the speed of light.

Nice article, going against the tide of the “everything is information” crowd. Still I think that the conclusion at the end is too pessimistic.

If I were an alien trying to figure out how a computer does certain things (like presenting a particular display), I could spend an incredible amount of time studying the physical properties of the components, starting from the lowest quantum perspective and going up to the higher levels of description consisting of wires, lumps of silicon, etc. Maybe, just maybe, in the end I would figure out that what really matters and can completely explain the particular behavior I am interested in are the voltage ranges existing at very particular points of the entire circuitry. That particular knowledge I acquired I can call “information” and it gives me a powerful tool for understanding a particular behavior (but not others – for instance, it does not help at all in calculating the amount of heat the computer is generating).

We could say that computers are a particular case: they were designed by men to be, among other things, understandable by us. Nature and evolution did not have any need to create living organisms that are completely understandable by us. On the other hand, we have discovered that evolution created something like the DNA, which is a pretty good example of natural “bits of information” and gives us a very powerful tool for studying development, inheritance, etc. (within limits, of course – the old belief “one gene, one trait’ is laughable in most cases, and the environment can also play an essential role).

In the case of the brain it would certainly be great if we could identify some “bits of information” that would allow us to describe in a compact and powerful way how our thoughts develop. But these bits might be extremely difficult to identify, and they might not have anything to do with the obvious targets of investigation like the synapses and their connections (the same way I could not understand a computer just by looking at the wiring connections, if I had no idea of the little “voltage level trick”). Or it might be impossible to find the bits because we are not smart enough, or because the brain operates according to some exotic non-computable physical phenomenon. We just do not know right now.

The ingrained belief in dualism– that a non-physical realm exists which is home to gods and all manner of magical, miraculous things–probably had survival value in early man and so would have been selected for in evolution. However, anything you can think of that actually exists can be traced back to its physical roots. The most common error in thinking about this is mistaking the abstract for the non-physical. For example, the word “relationship,” an abstract word (as opposed to, say, a concrete word like “computer”) has been used as an example of something non-physical, but there is nothing non-physical about it–the word and it’s definition and concept can be traced to its physical roots in the brain areas that store words and their meanings and concepts. Before the dawn of man, physical “relationships” existed among the stars and planets, there were just no sentient brains around to invent and physically house the word and its meaning and concept. As one noted neuroscientist has said, If you don’t get that the mind and everything else that exists is physical, just try harder.

A very well argued essay about the difficulties of understanding the brain/mind duality. My only comment would be that, IMHO, said duality is a gross oversimplification. Scientists tend to use too much reductionism – Occam’s Razor – in my view. But the material/mental world is much more complex and interactive than a binary analysis can address.

The conscious and subconscious mind have been likened to an iceberg. The conscious is the part that sticks out of the water, but the much bigger mass of the iceberg is below the surface. For example, Britannica.com’s coverage of information theory includes this observation; “ . . . the human body sends 11 million bits per second to the brain for processing, yet the conscious mind seems to be able to process only 50 bits per second.” (https://www.britannica.com/science/information-theory/Physiology) So, what happens to the other bits? And that’s just one second!

Complicating this further, I’ve come the view our mental evolution as the sum of our histories – both individually and socially. As human beings, that history has been cumulative for about 300 thousand years – give or take. But as life forms, that history goes back about 3.8 billion years. And as parts of the universe, our histories cover some 13.8 billion years! As the late great Carl Sagan once said: “If you want to make an apple pie, you must first invent the universe.”

On that note, I would just say that the 7.4+ billion of us now on the planet have 13.8 billion years of history in our brains; a teeny-tiny itsy-bitsy portion of which is in the conscious and subconscious mind.

I got goosebumps reading Kassan’s article. It resonates with what I wrote here in Comments about “What is the weight of a thought?”

I want to address the eternal problem of dualism raised by Kassan, but in a way from “left field.” Or, perhaps right brain hemisphere perception?

Decades ago I was a dancer. I knew nothing much about the mind, human anatomy or physiology at the time. But one day I was standing by myself with my eyes closed and I noticed that my whole body swayed slightly. I became curious as to where this sway originated. My ankles? Knees? Pelvis? Spine? I never found out. But, in what was actually a form of meditation, I found out something really goosebumpy….

As I payed attention to this swaying, I noticed what can only be called an energy moving up my spine and down the front of my body. It pulsated gently. If you visualize the shape of the spine from the side, you will see it is shaped like a wave, a snake, and apparently meant to move like one. My spine was undulating with this pulsating energy….

I believe what I perceived was what Traditional Chinese Medicine calls “qi” and Dr. Wilhelm Reich called “orgone” or the life energy….

I eventually became able to feel a field around my body and around others’ bodies. I called this a “feeld” because it was like a second nervous system: both sending and receiving sensory information. My students and I were, for example, able to send simple messages across a distance via our “feelds.”

Now, the connection with what this article is addressing:

The article is about dualism or non-dualism–a subject that is, itself, an historic dualism occupying the history of philosophy, religion, psychology and neuroscience. The trend has been to eliminate the problem by denying dualism or by denying one half of the duality–there is no mind, only electro-chemical impulses in the brain. But what I discovered was this….

Energy (this life energy) is the source of thinking, feeling, moving and perhaps being.

I perceived my energy BECOMING thinking, BECOMING emotion, BECOMING sensation, BECOMING movement!

I realized that the attempt to integrate mind and body, or to somehow resolve apparent duality between mind and brain–is happening because these people do not experience this energy and the fact that it is the SOURCE of thinking-feeling-moving-being.

To conclude: there is no duality because what seem to be mind and brain are, as it were, left hand and right hand JOINED, CONNECTED by the rest of the body!

Duality is only present when this connection is not perceived.

A lot of familiar history here, but it goes nowhere. (Hardly surprising, given the deep difficulty of the subject.) The final sentence is classic example of “It didn’t follow, it just came in last”.

Woo!