In mid-2020, the Skeptics Society launched the Skeptic Research Center1 (SRC) —a collaboration between the Skeptics Society and qualified researchers. The SRC was created to better understand what misconceptions most divide our society, and to empower the public with the knowledge necessary to think critically about current events. In the December 2020 issue of Skeptic, we reviewed the reports released from our first collaboration. In this article, we will review the findings from our second collaboration.

The Skeptic Research Center collaborated again with the Worldview Foundations Research Team,2 composed of sociologist Kevin McCaffree, psychologist Anondah Saide, and research assistant Marshall McCready. For this second collaboration, called the Civil Unrest and Presidential Election Study (CUPES), the team examined Americans’ social and political attitudes in light of the substantial social and economic unrest of Summer 2020. CUPES investigated how events such as the presidential election, the George Floyd protests, and the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the attitudes of fourteen hundred Americans regarding a variety of topics.

Our findings were released across nine reports published by the SRC between November 2020 and March 2021. The reports, as well as detailed supplementary statistical information, are freely accessible on the Skeptic Research Center website. The titles of these reports reflect the study’s key topics:

- Did Political Disunity Change in 2020? (#1)

- Intolerance Is Lower Than You Might Think (#2)

- Inequality and the Economy: Pandemic Tradeoffs (#3)

- Trust in Institutions (#4)

- Censorship Attitudes and Voting Preferences (#5)

- Outside of Politics, What Else Predicts Attitudes

- Towards Censorship? (#6)

- How Informed are Americans about Race and

- Policing? (#7)

- Why Are People Misinformed About Fatal Police

- Shootings? (#8)

- Has Time Spent with Family and Friends Declined? (#9)

Volunteers Needed

The Skeptic Research Center could use some help with a variety of tasks. If you are interested in volunteering with us, please fill out this form.

Below, we will discuss six central themes we identified across our findings. We’ll refrain from commenting about the potential implications of what we found because we elicited the interpretations of these findings from Skeptic readers such as yourself. These reader responses can be found at the end of this review.

Theme 1: Intra-Party Unity

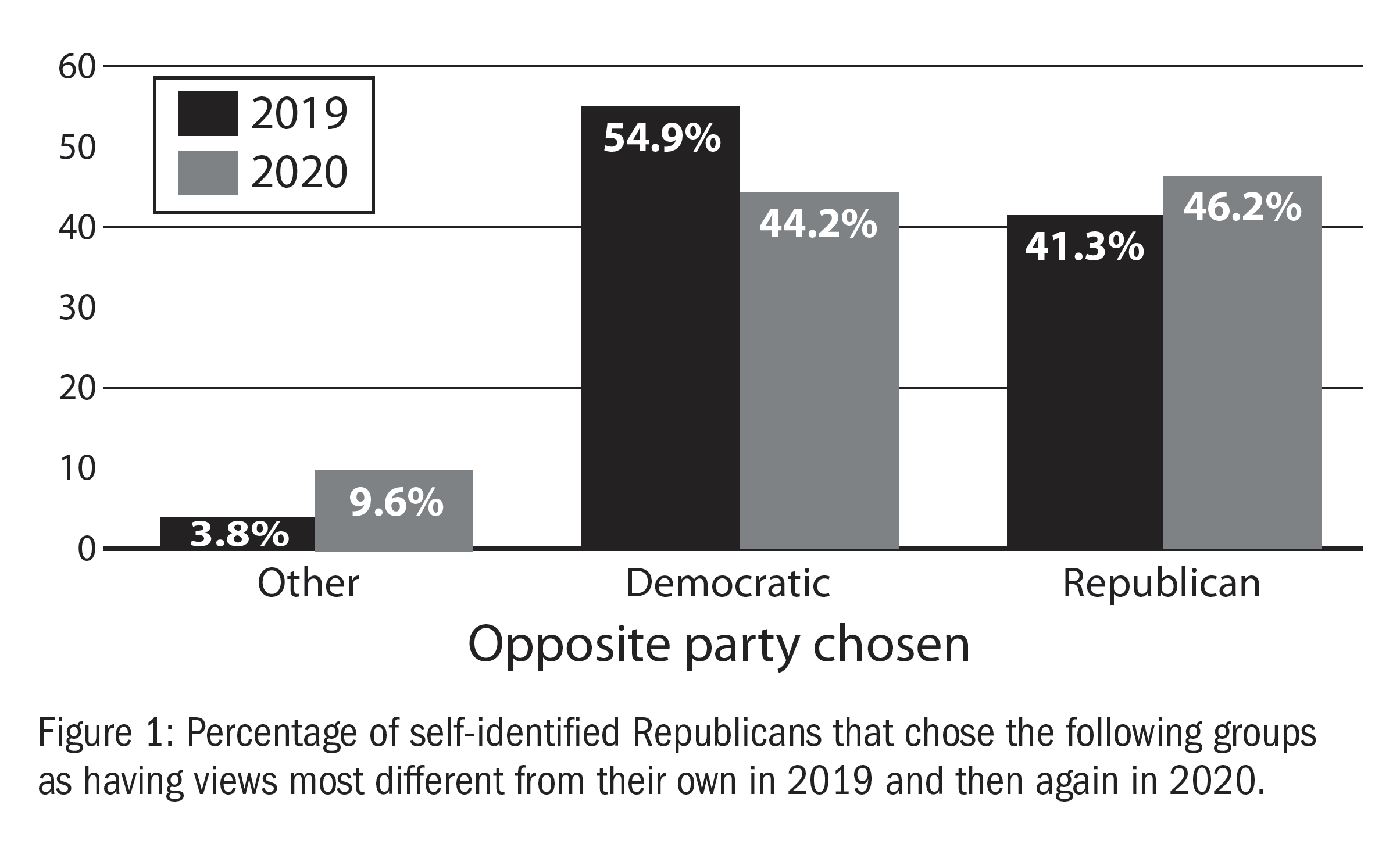

In a study we conducted in 2019, we found greater political disunity among Democrats than Republicans.3 In response to the question, “If you had to choose, which political group do you think is most different to your own political views, currently?” Democrats were statistically as likely to select the Democratic Party as they were to pick the Republican Party. However, in our follow-up study, we found that this in-group bickering amongst Democrats had begun to reverse. Between 2019 and 2020, it seems that the Republican Party became less unified, while Democrats became more unified.4 For example, from 2019 to 2020 there was a 5 percent increase in Republicans choosing their own party as being opposed to their political views, along with a 11 percent drop in Republicans choosing Democrats (see Figure 1 below). In contrast, the percentage of Democrats who reported greater political disagreement with their own party dropped about 10 percentage points during the same period.

Theme 2: Gender and Politics

Men and women differed systematically across several dimensions in our 2020 study (CUPES). Gender was related to support for freedom of speech and freedom of thought such that women, regardless of partisan affiliation, expressed significantly lower support than did men.5 We also found gender to be related to changes in socializing during the COVID-19 pandemic. We asked how often respondents spent time with friends and family in 2019 and 2020. Compared to their male counterparts, women of both political parties reported significantly greater reductions in time spent with friends.6

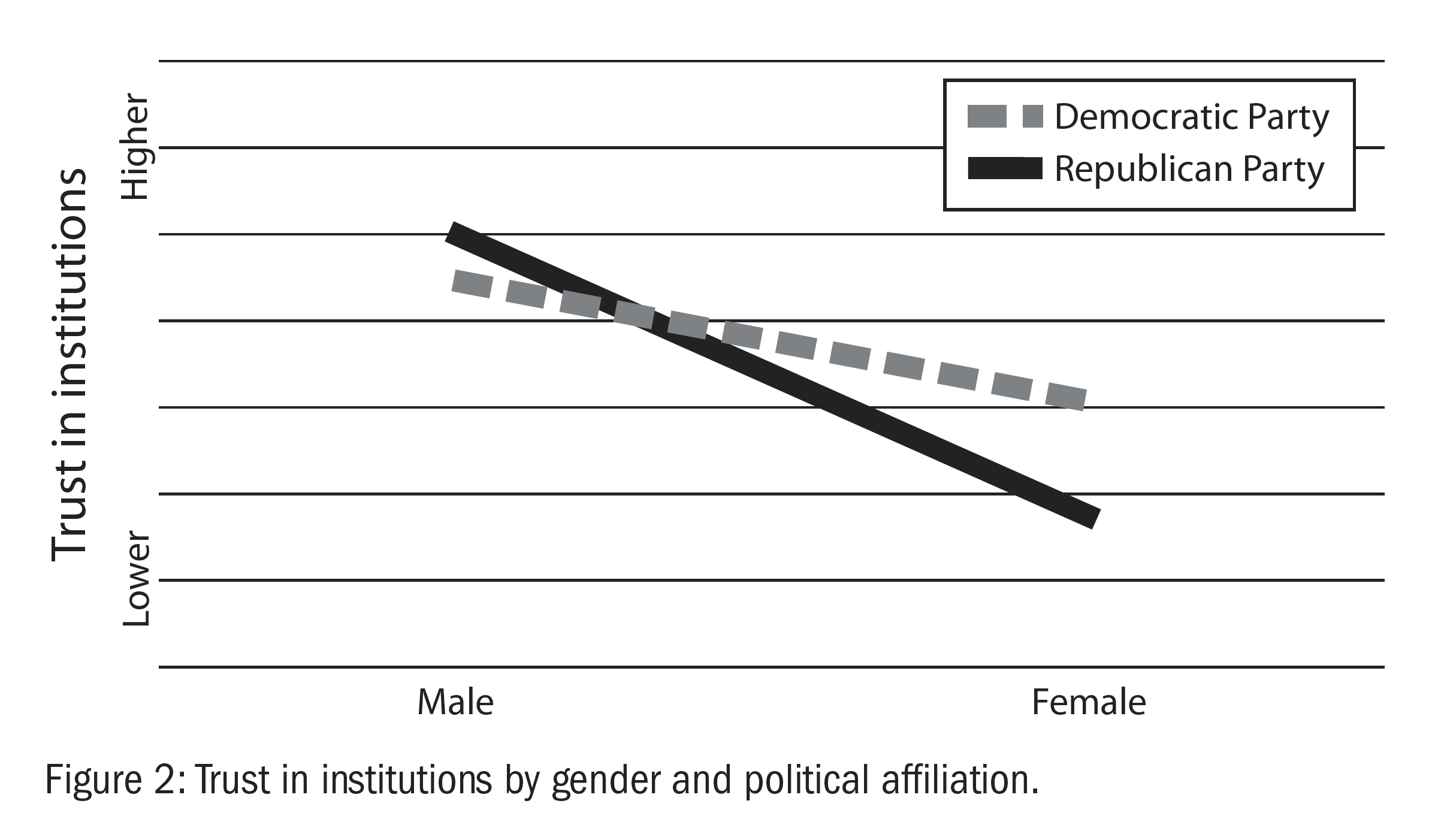

Republican women and Democrats of both genders reported similar reductions in time spent with family. In fact, only Republican men reported no decrease in time spent with family from 2019 to 2020. Finally, we found that women reported significantly lower levels of trust in institutions than men.7 Republican women, in particular, reported the lowest overall trust in the news media, political officials, hospitals and doctors, and educational institutions (see Figure 2).

Theme 3: Complexity of Political Tolerance

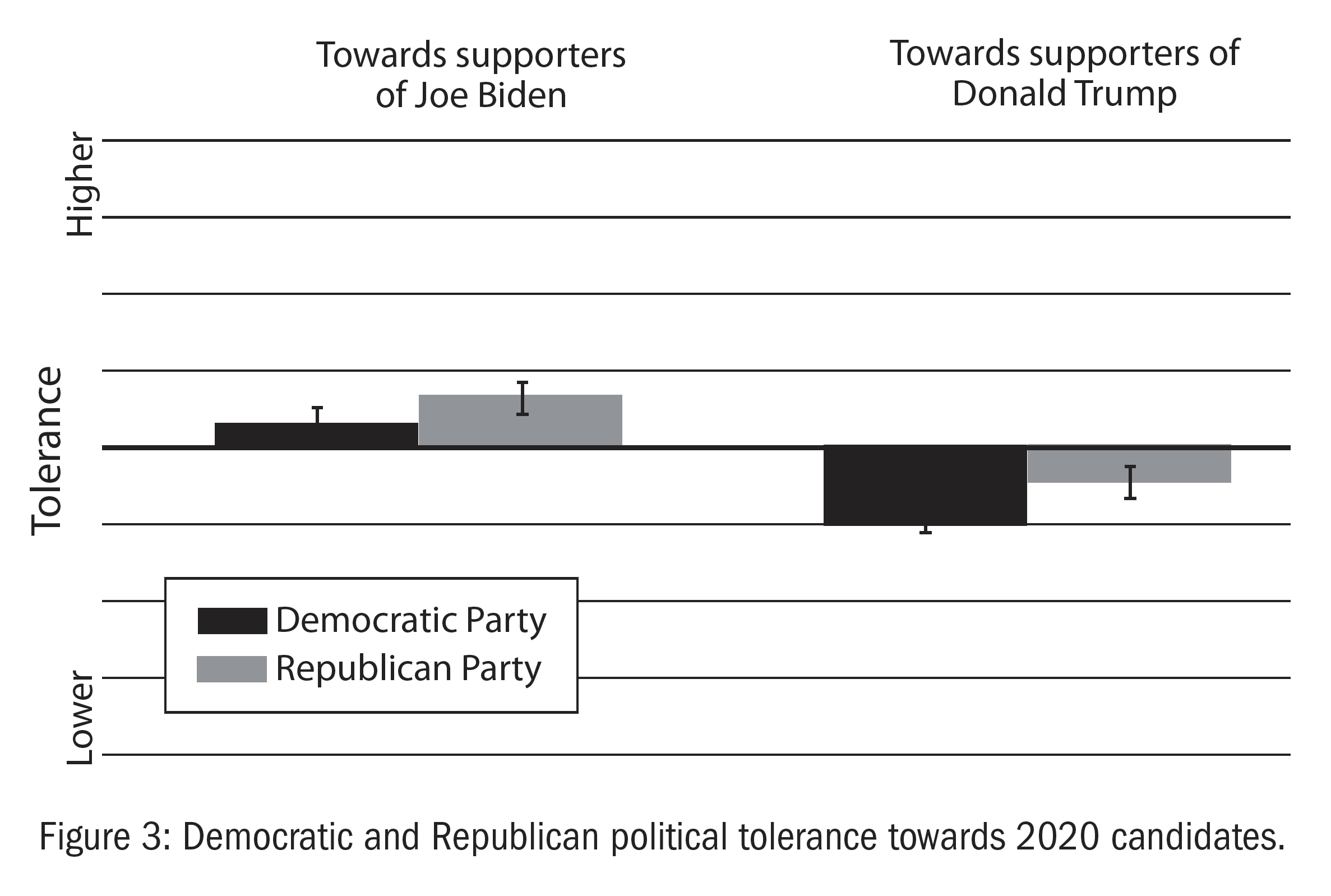

In the study we conducted in 2019 on political attitudes, Republicans and Democrats were both generally tolerant towards members of the political party they most opposed.8 On average, people in both parties told us that they would not be irritated if a member of the oppositional party was their neighbor, co-worker, local elected official, or the romantic partner of a family member. Findings from the 2020 follow-up study seem to confirm that a general tendency towards political tolerance has survived the recent civil unrest and public health crises —Republicans and Democrats reported tolerant views towards political rivals and did not differ significantly from each other in their level of tolerance.9

Even though the average American expressed tolerance for members of the opposite political tribe, they did not express similar levels of tolerance towards supporters of both major 2020 presidential candidates. Members of both parties who reported that Joe Biden holds views contrary to their own tended to report neutral or tolerant attitudes towards Biden supporters. On the other hand, Republicans and Democrats who reported disagreement with Donald Trump’s political views tended to express somewhat intolerant attitudes towards Trump supporters (see Figure 3).

Theme 4: Concern about the Pandemic

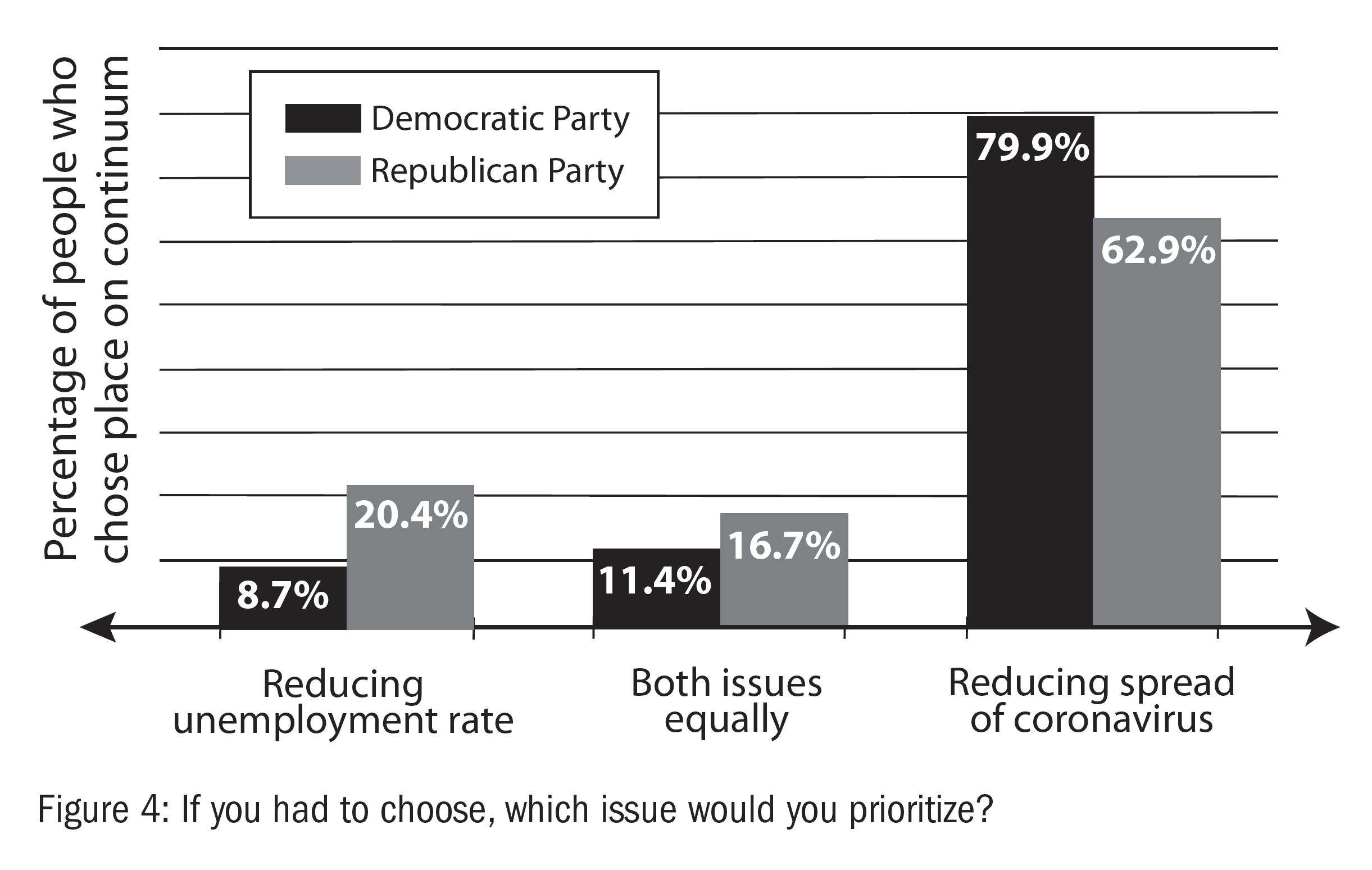

Overwhelmingly, both Democrats and Republicans prioritized reducing the spread of COVID-19 over other important issues, such as protesting racism and reducing unemployment. Almost 70% of Democrats and over 80% of Republicans reported they would prioritize reducing the spread of the Corona-virus over protesting against racism. While Democrats expressed greater concern about protesting racism and Republicans worried more about reducing unemployment (for example Figure 4 below depicts our findings reguarding unemployment), most respondents agreed that the pandemic should be prioritized.

Theme 5: Race and Policing

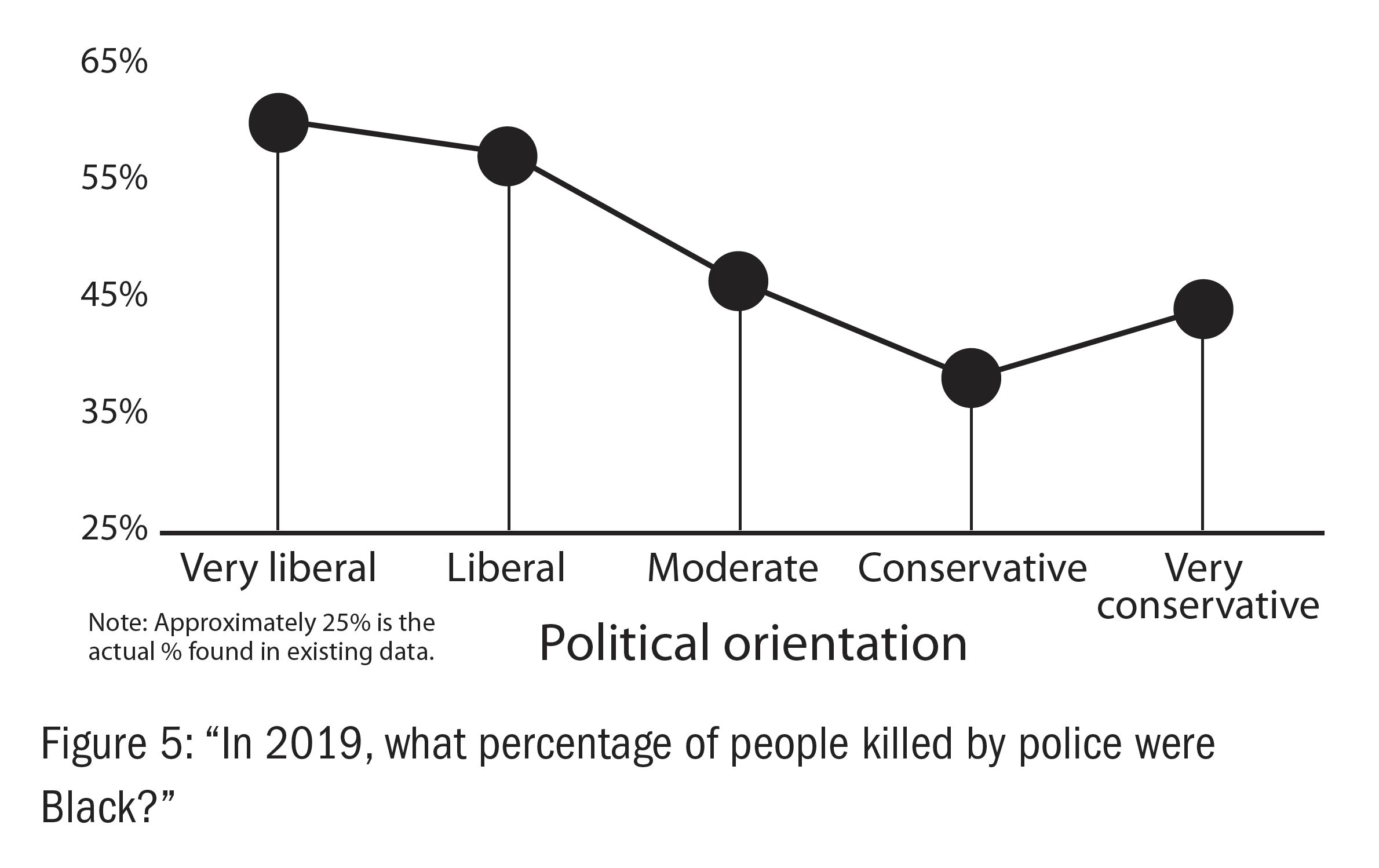

An important set of results emerged when we attempted to assess peoples’ knowledge about fatal police shootings and race. This topic was highly salient in 2020 due to the George Floyd and Black Lives Matter protests as well as formal efforts to defund the police. To examine how informed respondents were about the facts, we asked them to guess: (1) how many unarmed Black men were killed by police in 2019 (option categories ranged from “about 10” to “more than 10,000”); and (2) what percentage of people killed by police in 2019 were Black. Available evidence suggests the correct answers to these questions range between 13-27 and 23.4-26.7%, respectively.10

Respondents across the political spectrum overestimated their answers to the second question.10 However, accuracy for answers to the first question differed significantly by political orientation. Political liberals tended to answer much less accurately than conservatives. Over half of those reporting “very liberal” political views estimated that 1,000 or more unarmed Black men were killed by police, a likely error of at least an order of magnitude. Interestingly, participants with “very conservative” views were relatively less likely than those with “conservative” views to provide accurate answers to either question. The “very conservative” respondents tended to overestimate their answers more than their “conservative” peers.

Another finding of note was the effect of media on peoples’ perceptions of police violence. Our data revealed that the individuals most prone to estimation errors also reported high levels of trust in news media. Perhaps even more disconcerting, those in the sample with a graduate or professional degree reported the highest levels of trust in news media.

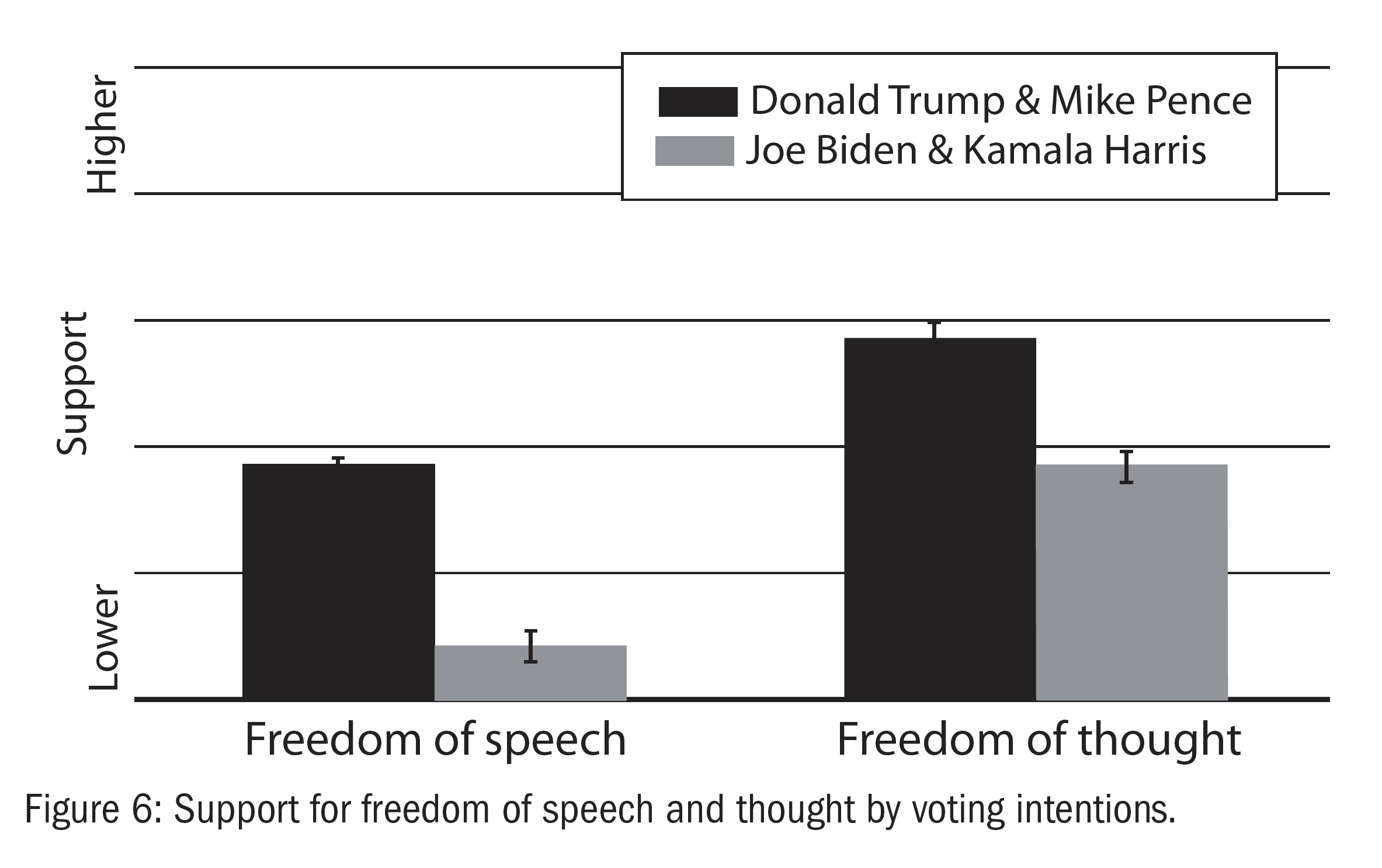

Theme 6: Censorship

To assess attitudes about censorship of speech and thought, we asked survey respondents to state how much they agreed with the following statements: “People should be allowed to say whatever they want, even if others think those words are harmful” and “People should be allowed to believe whatever they want, even if others think those beliefs are harmful.” For the most part, both those intending to vote for Donald Trump and those intending to vote for Joe Biden in the 2020 election expressed support for these statements. Support for freedom of thought exceeded that for freedom of speech among both groups. Trump voters, however, were more vehement in their support for freedom of thought and speech compared to Biden voters (see Figure 6). The lowest levels of agreement for either statement came from Biden voters, who expressed significantly less support for freedom of speech than those intending to vote for Trump.

As might be expected, we found that the more people expressed support for freedom of behavior, the less interested they were in censoring speech or thought.6 However, another finding, much more difficult to account for, surprised us: self-reported levels of loneliness and happiness each positively correlated with support for freedom of speech. Why might both lonelier and happier people be more supportive of free speech?

Additional Details

We summarized some of our key findings above, but there is much more to CUPES than we can convey here. We encourage you to review the nine reports on the SRC website for a complete list of our findings as well as a more detailed reporting of the results. There you can also find supplementary information about our methods of data analysis.

Implications and Skeptic Reader Commentary

What can we make of these finding? Over the last year, many of you have emailed [email protected] to share your thoughts on the reports summarized above. We thought it would be interesting to share the perspectives of some Skeptic readers. We asked some of you to share your thoughts on the findings presented in this article and below are the perspectives shared with us by five people, in no particular order. We are always looking for new perspectives on this work, if you have thoughts about future reports, be sure to email us.

Commentary 1

by Dr. Chris Ferguson, Professor of Psychology

Let me say at the outset that I believe our criminal justice system would benefit from many reforms, such as an end to the War on Drugs, more accountability for officer misconduct, the inclusion of mental health providers in some calls for service (but not “defunding” police which almost certainly will escalate violent crimes), and an end to “warrior training” programs for police which encourage them to be more aggressive. The murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer began a massive societal debate about police killings of Black men, but the actual data on race and policing are complex and defy simple narratives. At present, the news media appear locked in a pattern of highlighting police shootings of unarmed Black individuals but failing to report shootings of unarmed individuals of other ethnicities. This can create an availability heuristic, wherein news consumers overestimate the frequency of shootings of Black individuals, and underestimate the frequency of shootings of White, Latino and Asian individuals.

The results of the analysis of the public’s understandings of police shootings demonstrates that the public has been misinformed of the frequency of such shootings. Worryingly, this misinformation is associated with political affiliation, with those on the political left particularly likely to overestimate the frequency of shootings of unarmed Black men, which in fact remain rare (as are shootings of men of other ethnicities). This is not to suggest innocence on the part of right-aligned media which may simultaneously gin up polarization and xenophobia among right-aligned consumers.

In a country of 330 million people, even rare events will happen often enough to create a steady news media narrative. If the mainstream news media outlets (e.g., NYT, CNN, MSNBC, etc.) fail (as I believe they have) to properly inform the public of the complexities of the actual data (e.g., in some studies, social class indicators tend to predict shootings better than race), availability heuristics can create a mob mentality ruled by emotion that can push the public to support policies that will do far more harm such as defunding/abolishing police.

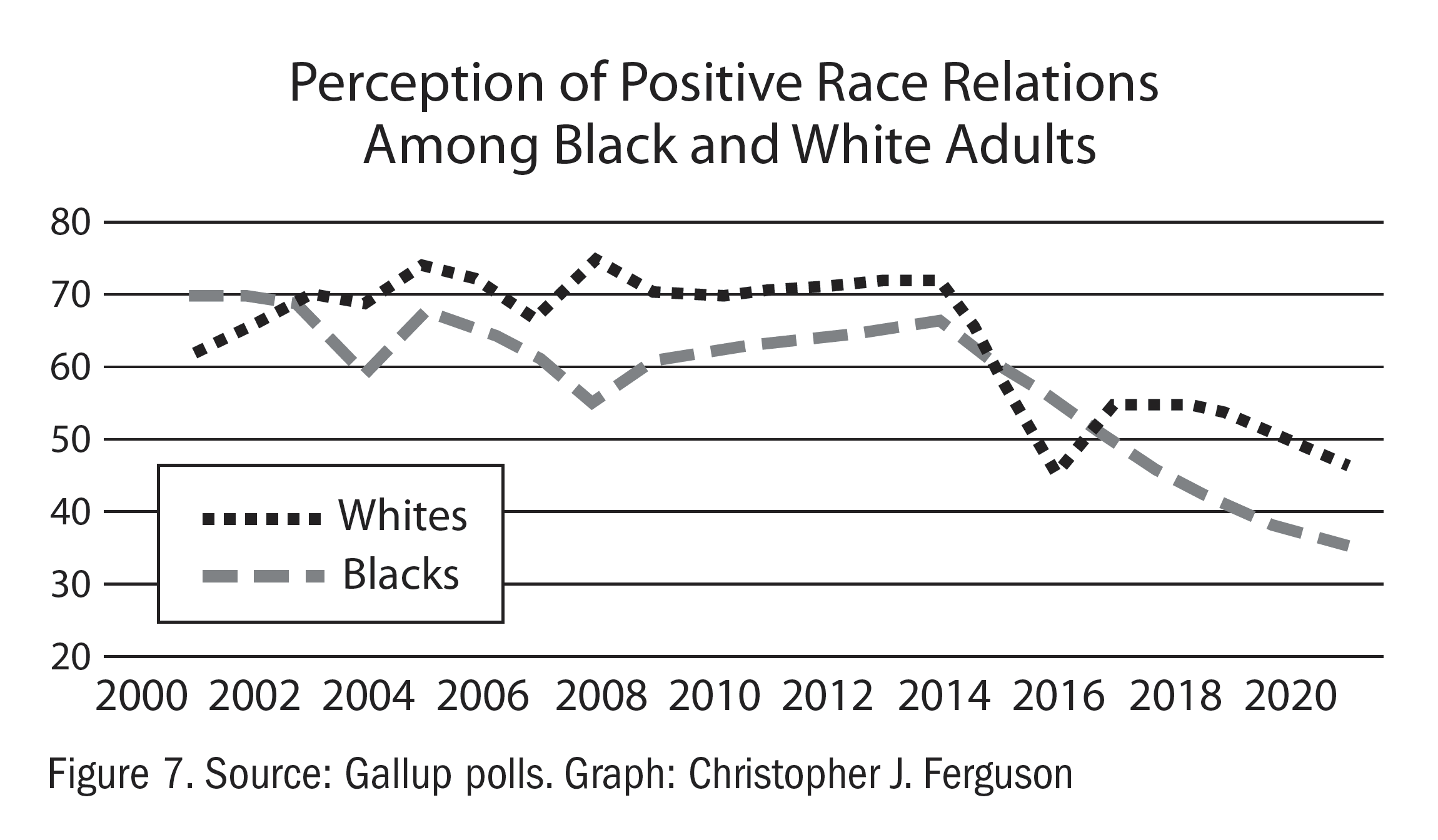

One last point: As Figure 7 above shows, we’ve seen a massive decline in race relations beginning in 2014. Before this, most Black and White people agreed that race relations were progressing positively. We need to understand why this changed. Undoubtedly, the reasons are complex, including increased focus on race and identity issues on both the left and right. But I believe the above study highlights a fundamental failure of the news media to properly inform the public.

Commentary 2

by Dave Porter, Former Professor of Behavioral Science and Leadership

To paraphrase Mark Twain, “It’s not the things we don’t know that cause problems; it’s the things we know that just aren’t so.”

Broadly, the CUPES Report results suggest things are not as bleak or polarized as many believe. This becomes more apparent as one focuses on the size of the reported differences rather than their statistical significance. Results suggested that 1 in 10–20 individuals have shifted their opinions over the previous year (CUPES-001). While statistically significant, this involves only a small subset of the population.

It was gratifying to see that we are still generally tolerant of those with whom we disagree (CUPES 002). However, the finding that intolerance is greatest against those we assume to be intolerant (i.e., supporters of the former president) is somewhat ironic. Extreme ideologies such as the much bandied-about trio of postmodernism, intersectionality, and Critical Race Theory incorporate ideas such as Herbert Marcuse’s11 that those identified as privileged (often former oppressors) do not warrant tolerance or equal protection under the law. This is worrisome as well as being basically unconstitutional.

Another worrying set of findings related to public and news disinformation/misinformation. The misconception that the killing of unarmed African Americans by police is common (i.e., liberals estimate that tens or even hundreds of thousands of African Americans are killed each year) demands more radical changes than are appropriate when one realizes the actual number of such deaths is less than 30. Similarly, a local survey study12 suggested that women’s heightened concern about hostile work or learning environments was associated with decreased support for freedom of speech and academic freedom as found in CUPES 006. This is not to excuse any single wrongful death or hostile environment or to deny the disproportionate danger that young African American men face. However, authentic and enduring improvements in the human condition are likely to continue only with a commitment to start with the facts and acknowledge what is working as well as what needs fixing.

Commentary 3

by Mark Newbrook, British Skeptical Linguist

It strikes me as strange that Democrats might be statistically as likely to select the Democratic Party as the political group most different from their own political views as they were to pick the Republican Party (or the equivalent for Republicans). I am not aware of any similar studies conducted in the UK or elsewhere, but I would certainly not expect such a pattern in the UK.

I suppose this pattern might arise if there had been a dramatic change of leadership (for instance, many “Old Left” Labour voters were unhappy with Tony Blair’s more “ecumenical” style when he became Prime Minister in 1997). Is this a result of some feature of American politics that is obscure to me? Of course, in countries like the UK, political commitments are less polarized. There are a number of minority parties which attract considerable levels of support and indeed have some candidates elected to represent constituencies.

I wonder if women, regardless of partisan affiliation, expressed significantly lower support than men did for freedom of speech and thought, and less trust in institutions, because many women are persuaded that —given inherent biases in the prevailing system and in various institutions —support for “freedom” often amounts in practice to support for the (perhaps covert) programs of already privileged groups (straight white males, etc.)

The issue of attitudes about police killings of African-Americans has been somewhat muddled by the relative lack of attention to the question of the higher frequency at which African-Americans come into contact with the police in the first place. Having said that, it is interesting, but perhaps not especially surprising, that political liberals (in the American sense of the word liberal) tended to overestimate, often seriously, the number of unarmed African-Americans killed by police. I suppose, as the “allies” of those killed, liberals have much more of an “axe to grind” in this respect. I find it much more surprising that many “very conservative” respondents also overestimated the number of African-Americans killed by police. I also find it surprising —and worrying —that respondents with a graduate or professional degree reported the highest levels of trust in news media (while also providing the least accurate estimates).

Finally, I wasn’t surprised that Trump voters were more vehement in their support for freedom of thought and speech than Biden voters, although this is an unfortunate situation for most skeptics, who generally combine support for freedom of thought and speech with “liberal” (American sense) or “moderate libertarian” political stances.

Commentary 4

by Ed Kreusser, Retired Medical Doctor

What was most astonishing to me in “The Trump Era” is not that someone like him maneuvered his way into the Oval Office but that, in spite of his many unmistakable inadequacies, so many Americans remain loyal to him. But then, “give the devil his due.” Trump has been nothing short of brilliant in identifying and dangling irresistible enticements to attract his minions.

Regarding the study results, it seems so ironic and inconsistent that “Trump voters are more vehement in their support for freedom of thought and speech…” In my view, their rigid loyalty to Trump reflects an indictment of our public educational system. That they claim to value and support freedoms of speech and thought suggests that they have only a very superficial understanding of these terms, perhaps only as patriotic mantras without actually having learned to appreciate their full meaning and how to utilize them as existential civic tools.

Freedom to write and think one’s thoughts is quite different and should be distinguished from deliberately lying to manipulate the opinions of others, especially now, using the awesome power of social media and the Internet. It has become all too obvious that a huge percentage of people are exceptionally poor at critical thinking and evaluating evidence, rendering them susceptible to causing terrible social damage (e.g., the unshackling of racist sentiments or the insurrection of January 6th).

The notion of “freedom of speech” has become sacrosanct in our culture. So much so that it often eclipses any associated sense of accountability, or consequences or responsibility for truthfulness. When originally penned by James Madison in 1791, it was a very different world with less potent forces at play. The original framers could not have anticipated today’s environment and how this ideal can now be distorted and weaponized to have very negative and destructive effects. Accordingly, the unfettered concept of freedom of speech is now dangerously obsolete and should be recast with appropriate restrictions. As S ren Kierkegaard said: “People demand freedom of speech as a compensation for the freedom of thought which they seldom use.”

Commentary 5

by J. Doe, Police Officer

As a cop, “based on my training and experience” is a phrase I frequently use in my reports and when presenting probable cause for arrest and search warrants. Americans’ opinions of police shootings and policing in general are also based on their training and experience. Unfortunately, much of that experience is from cable news, TV dramas, movies, and the occasional traffic stop.

With regard to these findings on officer involved shootings, it’s no surprise that respondents’ political leanings affected their opinions. Our divided (and often fictional) news media landscape caters to, and reinforces, each team’s perspective on the issues at hand. Another significant factor is a lack of any general public understanding of policing. To demonstrate my point, see if you can answer these basic law enforcement-related questions:

- What is the difference between reasonable suspicion and probable cause?13

- Per your state’s general statutes, when is an officer justified to use deadly force?14

- Under what conditions should an officer read a person their Miranda rights?15

People’s overestimation of their personal expertise frequently shows up when police use-of-force is involved. I hear comments questioning the number of officers needed to restrain a suspect, why de-escalation wasn’t used with an active shooter, or even why an officer didn’t shoot a weapon out of someone’s hand. These kinds of comments suggest a view of reality utterly distorted by action movies and lacking in any experience with violent people.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 26.3 (2021)

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

If I watched video from 10 heart surgeries in which the patient died, I’m not sure I could attribute any single death to malicious intent, error or negligence by the surgeon. Based on my training and experience in surgery, I think I could spot a doctor dropping a Junior Mint in a chest cavity. But beyond that, I would make no judgments; I have no real or perceived expertise in surgery.

Critics correctly point out that because police are entrusted with tremendous authority and responsibility, a shooting by an officer needs special attention. I agree, but this point is often made from the perspective that all officer-involved shootings were made in error, and it often ignores the function officers are responsible for in society. When a crime involving a gun occurs, the police are tasked with responding first. In many circumstances officers are expected to prevent future shootings by arresting violent offenders or through patrols in hot spots. We can’t separate America’s officer-involved shootings from American gun culture and gun crime. Overall crime rates are down, but gun and drug-related crime is concentrated in lower income areas. This is likely a factor in the divided opinions based on education level, since higher education generally indicates higher income/wealth. It’s easy to maintain a negative view of police when you don’t need their services. ![]()

Volunteers Needed

The Skeptic Research Center could use some help with a variety of tasks. If you are interested in volunteering with us, please fill out this form.

About the Authors

Dr. Anondah Saide has a Ph.D. in psychology from the University of California, Riverside. She is a visiting assistant professor at the University of North Texas and co-directs the Worldview Foundations Research Team.

Dr. Kevin McCaffree has a Ph.D. in sociology from the University of California, Riverside. He is an assistant professor at the University of North Texas and co-directs the Worldview Foundations Research Team.

Marshall McCready is a sociologist and market researcher. He earned his master’s degree from the University of North Texas.

References and Footnotes

- https://www.skeptic.com/research-center/

- https://worldviewfoundationslab.wordpress.com

- SPAS-001

- CUPES-001

- CUPES-006

- CUPES-009

- CUPES-004

- SPAS-002

- CUPES-002

- CUPES-007

- Marcuse, H. 1965. “Repressive Tolerance.” In A Critique of Pure Tolerance, Wolff R.P., Moore, B., and Marcuse, H. (eds.) Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Porter, D. 2020. “Identity, Belief, Perceptions, and Judgments of Hostile Environments and Academic Freedom on a Liberal Arts College Campus.” Kentucky Academy of Sciences, Annual Conference, 7 Nov. (Presentation available at https://davesfsc.com)

- Reasonable suspicion that a crime has occurred, is occurring, or will soon occur allows an officer to temporarily detain an individual to investigate. This is a low bar of evidence. Probable cause is required to make an arrest and requires a higher bar of evidence —facts must suggest it is more probable than not that the suspect committed a violation of the law.

- Every state’s use of force laws are different. Have you read yours? You may be surprised.

- Custody (not free to leave) and questioning about the crime. Incriminating statements sans questioning, and questioning sans custody aren’t protected by Miranda.

This article was published on January 31, 2022.

Some comments to the authors of this paper.

1. Figure 2 should be a bar graph, not a line graph, which implies a within subjects design and a relationship that does not exist in those data.

2. When presenting your findings, it is better science writing to avoid adjectives when evaluating your results.

Case in point:

“Perhaps even more disconcerting, those in the sample with a graduate or professional degree reported the highest levels of trust in news media.”

Why do you need to express your feelings here? Report the data and let the reader experience their own feelings.

Dr. Kreusser is substantially correct. The “huge percentage of people who are exceptionally poor at critical thinking, etc.” and the demagogues who manipulate the ignorant were the nightmare of the U.S. founding fathers.