Is psychotherapy effective? Which of the many types is best? Are certain therapies better suited to treat certain problems? How can you rationally choose a therapist? Is it better to pick a psychiatrist, a psychologist, or some other type of counselor? There is a veritable cornucopia of individuals offering advice about mental health issues, from celebrities to life coaches to pastors to concerned friends, some with formal training and some with no credentials at all. Does psychotherapy ever make patients worse? What is the risk-benefit ratio?

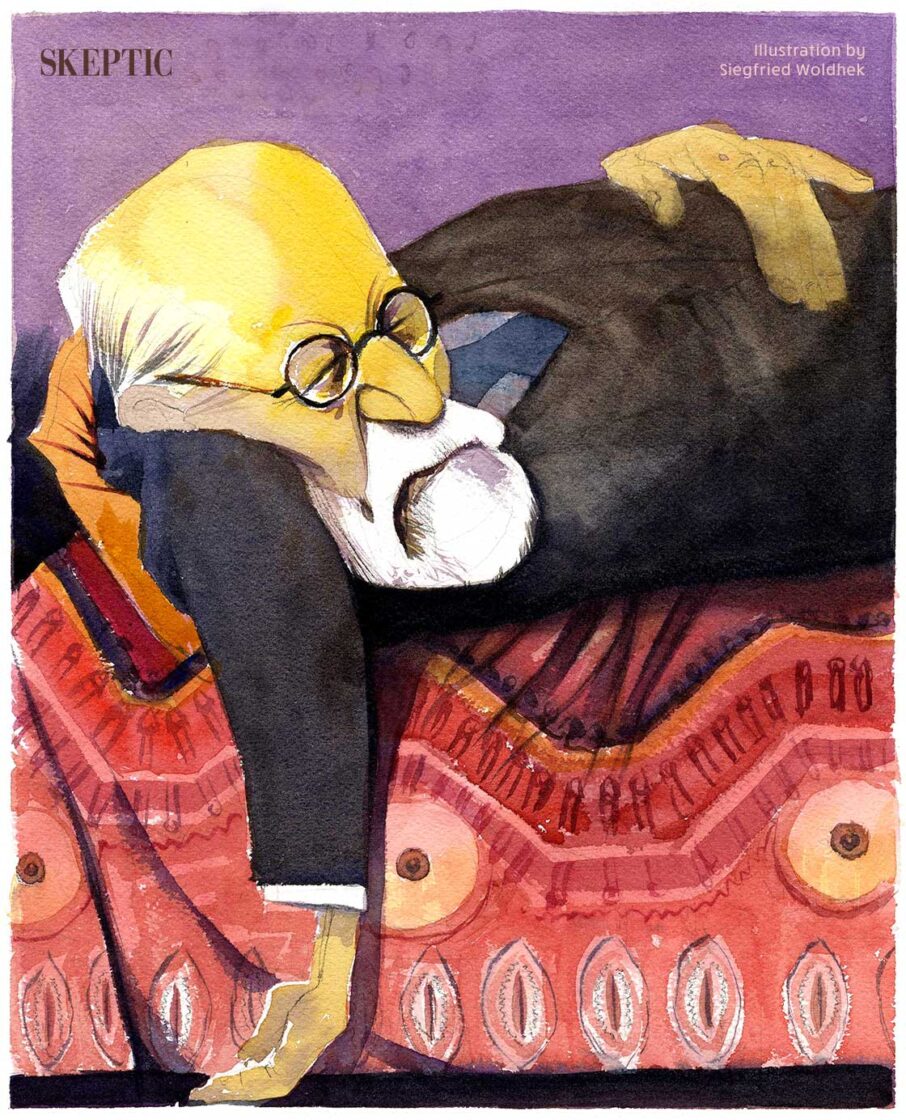

We are handicapped by a lack of information. In his recent book Fads, Fakes and Frauds, the Polish psychologist Tomasz Witkowski likens the current situation to the old Indian fable of the blind men trying to describe an elephant. One feels the trunk and says an elephant is like a snake, another feels the knee and says an elephant is like a tree, a third feels the tail and says an elephant is like a rope, and so on. They only knew about the part they had touched, and they couldn’t accept the conflicting reports of the other blind men, so they remained ignorant of the full picture of the animal.

Similarly, proponents of each modality of psychotherapy give us their subjective impressions about the success of their chosen method. No one has the whole picture; no one can provide an objective report about the whole field. There aren’t even any basic numbers. No one knows how many therapists there are, or how many patients consult them, or what the actual outcomes are, or what happens to the patients who leave therapy for one reason or another, or how many are harmed by therapy. No therapist knows whether their method is more (or less) effective than the methods of others.

By the most recent account, there were over 600 types of psychotherapy. There may be more. Some are no longer used and some have changed their names, but new ones are constantly appearing. Most of them have never been tested for efficacy, and only a few have been demonstrated to be effective and then only for certain problems. Wikipedia has an alphabetical list of psychotherapies.1 To give just one example, each from the first half of the ABCs: attachment therapy, biofeedback, cognitive behavioral therapy, dreamwork, emotional freedom technique, Freudian psychoanalysis, Gestalt therapy, hypnotherapy, interpersonal reconstructive therapy, journal therapy, logotherapy, Morita therapy. Where would you begin to choose? Life isn’t long enough to try them all or even to understand them all, much less put them to the test.

What if there were a similar situation for other treatments? What if there were 600 different ways of treating a hip fracture? What if 600 different antibiotics were being used to treat strep throat? How could doctors rationally choose? They would look for the scientific evidence. There would be clinical studies that used control groups. Outcomes would be meticulously tracked. We would have objective data. Why should psychotherapy be exempt from the usual methods of scientific investigation?

When conflicting data emerge from different studies, meta-analyses and systematic reviews of all the published data can help resolve the conflict. A 2017 review found that while most of the studies favored psychotherapy, effectiveness was confirmed in only seven percent.2

A 2021 review of over 400 studies3 found that mindfulness-based and multi-component interventions showed some efficacy and singular positive psychological interventions, cognitive and behavioral therapy-based, acceptance and commitment therapy-based, and reminiscence interventions “made an impact.” However, effect sizes were moderate at best, and the quality of the evidence was low-to-moderate.

Not very impressive after a century of research.

In his book, Tomasz Witkowski revealed that some therapists who are aware of the efficacy studies say they are following evidence-based methods; but in practice, they fail to do so, thinking the methods are not appropriate for their patients. And he says some of them consciously discard crucial information.

When Psychotherapy is Harmful

Anything that has effects can have side effects, and yet 79 percent of effectiveness studies failed to mention negative effects. It’s hard to determine how many patients are harmed. Only about two percent of psychologists are sued for malpractice and it has been estimated that up to 80 percent of liability cases are won by the therapists. If they lose, the punishment is usually trivial: from reprimands to expulsion from an organization they belong to. Afterwards, they are usually free to continue practicing.

Disproportionate power exists in the provider/patient relationship. Patients tend to feel helpless and have poor self-esteem. They trust the therapist as a knowledgeable expert who will know how to solve their problems. However, that may not be true. Jeffrey Masson, an experienced psychotherapist, wrote a book titled Against Therapy: Emotional Tyranny and the Myth of Psychological Healing. In it, he confessed that many times he was acutely and painfully aware of his inability to help, felt bored, uninterested, irritated, helpless, confused, ignorant, and lost. When he could offer no genuine assistance, he never acknowledged this to a patient. And he believed that everything he experienced was felt by other therapists as well.

Adverse effects of psychotherapy can be anything from crying during a session to attempted suicide. Harms may be caused by the therapist or by the therapy. According to psychologist Noam Shpancer, estimates for the incidence of negative outcomes from psychotherapy have varied from three percent to 20 percent.4 Accurate numbers are hard to come by, for several reasons that he explains.

Unscrupulous therapists may prioritize their own needs (exploitative, voyeuristic, narcissistic) over those of the patient. Some may indulge in inappropriate sexual behavior. And even well-meaning ethical therapists who adhere to standard practices can do harm. For example, therapy may lead to excessive self-absorption, adopting a victim role, and reduced capacity to make independent judgments. Becoming dependent on a therapist may impair the development of coping skills.

One example of well-documented harm from psychotherapy is that of recovered memory therapy, once controversial and now scientifically discredited. Its practice is no longer recommended by any mainstream organization. Practitioners believed that memories of childhood traumas such as sexual abuse could be repressed and forgotten but were retained in the subconscious and could still affect adult behavior. This claim is not supported by any evidence. Therapists offered to help patients remember the forgotten trauma, using treatments that included psychoanalysis, hypnosis, journaling, past life regression, guided imagery, and even the use of sodium amytal for interviews.

What these procedures were really doing was creating false memories. Research by Elizabeth Loftus and others has shown that it is easy to create false memories which can sometimes seem more real than true memories. The False Memory Syndrome Foundation was created to assist those falsely accused of abusing children. Some individuals were jailed and families were destroyed because of “memories” of abuse that never happened. The only way to determine that a “recovered” memory is true is to find external confirmation.

Studies have found other harms to patients.5 The Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) program was counterproductive: it increased drug use. At-risk adolescents in the Scared Straight program were more likely to offend. Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) has been shown to worsen symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety scores. In a small study of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD in young children, 10 percent of patients experienced a negative event such as fear of the dark, even enuresis or encopresis (urinary or fecal incontinence, respectively). Some experienced cognitive therapists suggest that Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) can be toxic6 to some individuals, particularly those with obsessive personalities, by increasing worry and introspection, fueling rather than relieving anxiety and depression.

Some psychotherapies are brief; others, like Freud’s psychoanalysis, go on interminably. Freud behaved more like a witch doctor than a scientist. He has been discredited for fabrication and making claims that can’t be tested. Psychoanalysis is controversial and its effectiveness has been contested, but it continues to be widely taught and practiced. Albert Ellis has documented the many ways that psychotherapy is frequently harmful to patients.7

The FDA requires that the side effects of drugs be listed along with the benefits. Unfortunately, there are no such warnings required for psychotherapy. Isn’t this a double standard? Robyn Dawes, in his book House of Cards,8 writes a scathing critique of psychology and psychotherapy as a being such a precarious structure built on myth rather than science:

the rapid growth and professionalization of my field, psychology, has led it to abandon a commitment it made at the inception of that growth. That commitment was to establish a mental health profession that would be based on research findings, employing insofar as possible well-validated techniques and principles… Instead of relying on research-based knowledge in their practice, too many mental health professionals rely on “trained clinical intuition.”

Dawes is particularly incensed by professionals who make assertions in commitment hearings and sexual abuse cases based on psychological techniques that have proven to be invalid. He says there is a real science of psychology; however, it is being ignored, derogated, and contradicted by the very people who should know better.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 28.1

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

Some psychotherapeutic interventions have been shown to be no better than talking with a friend. Pilot programs in underserved areas are showing that brief training can enable laymen and non-specialist health workers to provide effective psychotherapy.

In Goa, Wellcome-funded MANAshanti Sudhar Shodh (MANAS),9 led by Professor Vikram Patel, trained non-specialist health workers to deliver psychosocial interventions, including psychoeducation, yoga, and interpersonal therapy. They ran a trial of 2,796 people having common mental disorders and found 65.9 percent of those who were treated with a collaborative care approach, including psychosocial interventions, recovered after six months, compared to just 42.5 percent in the control group.

The bottom line: psychotherapy works to help some patients, but we have no idea why. It is not based on solid science and there is, at present, no rational basis for choosing a therapy or a therapist. ![]()

About the Author

Harriet Hall, MD, the SkepDoc, was a retired family physician, former flight surgeon, and retired Air Force Colonel who writes about medicine, pseudoscience, alternative medicine, quackery, and critical thinking. She was a contributing editor and regular columnist for both Skeptic and Skeptical Inquirer magazines and an editor at ScienceBasedMedicine.org, where she wrote an article every Tuesday since its inception in 2008. She wrote the book Women Aren’t Supposed to Fly: The Memoirs of a Female Flight Surgeon. The full texts of all her many hundreds of articles can be read on her website www.skepdoc.info. This was the last column Harriet wrote for Skeptic before she died in January 2023.

References

This article was published on April 14, 2023.