12-11-21

Now through Sunday

25% off everything at Shop Skeptic

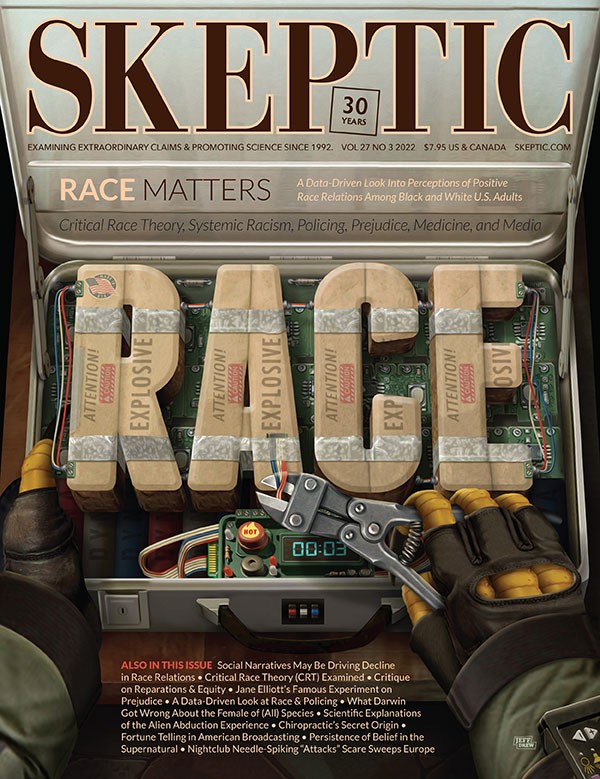

It’s our best sale of the year: the Skeptic 5-day Sale (November 21 through November 25, 2012, PST). Shop now and save 25% off everything at Shop Skeptic, including: books, DVDs, print magazine subscriptions, hoodies, t-shirts (and other cool swag), as well as back issues of Skeptic magazine.

All orders placed at shop.skeptic.com between Wednesday, Nov. 21 through Sunday, Nov. 25 (PST) will be discounted by 25% at checkout. Sale prices shown below include the 25% discount mentioned above. Digital subscriptions & digital back issues are not included in this sale; they are sold within the Skeptic Magazine App, available through Apple, Google & Amazon.

Order in time for Christmas delivery

Order by December 10 for shipments outside the US.

Order by December 19 for shipments inside the US

See our Holiday Shipping page for complete details.

T-Shirts, Hoodies

& Other Swag

Skeptic Hoodies

by American Apparel $46.00

A fitted, sporty unisex zip hoodie in luxurious Flex Fleece fabric: a unique 50/50 cotton/poly blend that offers warmth without being overly bulky. Pre-washed for minimal shrinkage. Contrasting white finished polyester drawcord, metal zipper. Kangaroo pocket. If you are not familiar with how American Apparel fits, refer to the sizing chart below before placing your order. If you don’t like a snug fit, we suggest ordering a size larger than you would normally order from other manufacturers.

ORDER hoodies

Skeptic T-Shirts

by American Apparel $18.00

Made of 100% fine jersey knit cotton, ring-spun and combed for superior softness and strength. Our unisex fine jersey short sleeve T-shirts, by American Apparel, are the softest, smoothest, best-looking T-shirts available anywhere. If you are not familiar with how American Apparel fits, refer to the sizing chart below before placing your order. If you don’t like a snug fit, we suggest ordering a size larger than you would normally order from other manufacturers.

ORDER T-shirts

Skeptic Lapel Pin $10.00

This tie-tack style metal pin has gold-colored SKEPTIC lettering with a contrasting black background. It’s a great size for a lapel or tie — about 25mm × 6mm (1″ × .25″). It comes in a classy little plastic box suitable for gift-giving. (Note: image not shown actual size.)

ORDER the lapel pin

Skeptic Bumper Sticker

1 for $4 or 3 for $8

Designed to withstand the elements, these self-adhesive bumper stickers, made from the highest quality weather resistant and laminated vinyl, are ideal for use on vehicles, windows, refrigerators, school lockers and binders, or just about anywhere you want to stick them. DIMENSIONS: 11.5″ wide × 3″ high. Want something smaller? Check out our 5″ × 2.75″ sticker. ORDER the bumper sticker

Print Subscriptions

& Back Issues

Skeptic Magazine Subscriptions

starting at $30.00

A subscription to Skeptic magazine, the definitive skeptical journal, makes a perfect gift that lasts all year. Promoting science and critical thinking, our articles explore and inform. Buy it. Share it. Help us make the world a more rational place by defending the role of science in society!

ORDER a print subscription

ORDER a gift subscription

Skeptic Magazine

Back Issues $6.00

Don’t miss this opportunity to complete your collection of Skeptic magazine by getting the back issues you’re missing in your library. Volume 17, number 1 (our Scientology issue) is one of our most popular issues. Order a copy for a friend and introduce them to skepticism. Bound with every issue of Skeptic magazine is Junior Skeptic: the skeptical movement’s most sustained and substantial educational outreach project for children. ORDER back issues

Must-Have Skeptical

Reference Guides

How to Debate a Creationist

by Michael Shermer $5.00

This 28-page booklet is perfect for anyone who wants to know how to converse with a creationist. It contains 25 creationist arguments and 25 evolutionist answers (some philosophic and some scientific); describes what the theory of evolution is and isn’t and explains why creationism is not science; provides an in-depth understanding of Intelligent Design, its pitfalls and logical fallacies, and much more.

ORDER the booklet

The Baloney Detection Kit

by Michael Shermer & Pat Linse $5.00

This 16-page booklet, designed to hone your critical thinking skills, includes suggestions on what questions to ask, what traps to avoid, specific examples of how the scientific method is used to test pseudoscience and paranormal claims, and a how-to guide for developing a class in critical thinking.

ORDER the booklet

A Skeptic’s Guide to

Global Climate Change

by Donal Prothero $5.00

Distinguish climate change skepticism from climate change denialism; get 25 answers to classic climate denier arguments; examine a summary of the scientific evidence and climate data and discover what’s behind the debate on climate change; find out why scientists think climate is changing and how we know global warming is real and human caused. This booklet has 28 pages at 8.5 × 11 inches.

ORDER the booklet

The Skeptic’s Dictionary

by Robert Carroll $19.95

The definitive short-answer debunking of nearly every thing skeptical with nearly 400 definitions, arguments, and essays on topics ranging from acupuncture to zombies. Detailed information on all things supernatural, occult, paranormal, and pseudoscientific, including: alternative medicine; cryptozoology; extraterrestrials and UFOs; frauds and hoaxes; junk science; logic and perception, and more. An invaluable reference.

ORDER the dictionary

On Evolution

Evolution: How We and All Living Things Came to Be

by Daniel Loxton $18.95

Hailed as a “tour-de-force of science writing,” Evolution was crowned in 2010 with Canada’s largest literary prize for children’s science books: The Lane Anderson Award for Best Science Book for Young Readers. Combining lavish illustrations, breezy prose, and deep science, this primer for ages 8–13 has been applauded by expert reviewers including the National Science Teachers Association, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the National Center for Science Education.

ORDER the hardback

Evolution: What the Fossils Say & Why it Matters

by Donald Prothero $30.00

This book, which has received rave reviews, is one of the best books explaining evolution and new discoveries of the incredibly rich fossil record; plus a no holds barred critique of the claims of creationism and Intelligent Design. Over 200 illustrations. Michael Shermer says of the book: “Prothero’s visual presentation of the fossil and genetic evidence for evolution is so unmistakably powerful that I venture to say that no one could read this book and still deny the reality of evolution.”

ORDER the hardback

ORDER the lecture on DVD

The Greatest Show on Earth

by Richard Dawkins $16.99

This New York Times bestseller is a fierce counterattack against proponents of “Intelligent Design.” Educators are being asked to “teach the controversy” behind evolutionary theory. There is no controversy. Dawkins sifts through rich layers of scientific evidence to make the airtight case that “we find ourselves perched on one tiny twig in the midst of a blossoming and flourishing tree of life and it is no accident, but the direct consequence of evolution by non-random selection.”

ORDER the paperback

Why Darwin Matters: The Case Against Intelligent Design

by Michael Shermer $13.00

Evolution happened, and the theory describing it is one of the most well founded in all of science. Then why do half of all Americans reject it? Historian of science, Michael Shermer, defuses these people’s fears about evolution by examining what it really is, how we know it happened, and how to test it. He examines the difference between supernatural (creationism) v. natural (evolution) design and how evolution can explain complex design.

ORDER the paperback

ORDER the abridged audio CD

Critical Thinking Classics

Flim-Flam!

by James Randi $22.00

Flim-Flam, a classic masterpiece—and the bible of the skeptical movement—is Randi’s account of dozens of his personal investigations into the paranormal that no skeptical bookshelf should be without. With an Introduction by Isaac Asimov, this book includes Randi’s investigations of the Bermuda Triangle, alternative medicine, Transcendental Meditation, ESP, PSI, and how Sir Arthur Conan Doyle got taken by fake fairy photographs (despite Houdini’s debunking of them).

ORDER the paperback

The Faith Healers

by James Randi $25.00

This book is Randi’s greatest investigation and exposé of Peter Popoff, W.V. Grant, Pat Robertson, and Oral Roberts, as seen on the Tonight Show. Steve Martin’s Leap of Faith was based on this book and Randi won a MacArthur “Genius Award” for this work. The Toronto Sun calls it, “A fascinating look at a world of misplaced faith and blind trust that seems more appropriate to the Dark Ages than to the end of the 20th century.”

ORDER the paperback

The New Age: Notes of a Fringe Watcher

by Martin Gardner $26.00

This book is a classic of skeptical literature filled with thirty-three diverse chapters: a bountiful offering of the delightful drollery and horse sense that has made Martin Gardner the undisputed dean of the critics of pseudoscience. It is also a quick way to get up to speed on many topics.

ORDER the paperback

Scientific Paranormal Investigation

by Benjamin Radford $16.95

“An excellent primer on how any reasonably observant person interested in looking into paranormal claims can do so without having to invent the art from scratch. The real paydirt here is Ben’s own detailed accounts of events he’s personally looked into… Ben Radford knows his calling. Read, consider, and learn. It’s all here.” —James Randi

ORDER the paperback

Great for Kids!

The Magic Detectives

by Joe Nickell $15.00

Encourage scientific awareness in children and have them see it as challenging, interesting, and just plain fun! Nickell presents 30 brief mystery stories with clues embedded in each story. At the end of each mystery, the reader can turn the book upside down and see if they have come to the same conclusion reached by the professional ‘magic detectives.’ Included are examinations of the ‘mummy’s curse’, Bigfoot, haunted stairways, walking on fire, ancient astronauts, the Reverend Peter Popoff, the Amityville Horror, the Loch Ness monster, poltergeists, and more.

ORDER the paperback

Maybe Yes, Maybe No

by Dan Barker $16.00

A good book to inspire discussion with your children about religious belief systems. This book encourages children to ask questions and suggests ways to apply the scientific method to reach conclusions. In addition to religion, the book provides examples from other topics such as UFOs, prophesy, out of body experience, dowsing, levitation, astrology, horoscopes, ESP, telepathy, and telekinesis. Simple straightforward text in a cartoon style. Kids learn how to listen and ask questions; how to seek a simple explanation; what tools and rules a scientist uses to check things out. For ages 7–10 years.

ORDER the paperback

Sasquatches From

Outer Space

by Tim Yule $15.00

A nice beginning book written in a chatty cheerful style to develop future critical thinkers. Covers astrology, Bigfoot, the Bermuda triangle, ESP, corp circles, the Loch Ness Monster, Vampires, and UFOs and aliens. Teaches basic critical thinking skills that will help young people who are bombarded by fantastic claims to distinguish between fact and fiction. Plenty of common sense examples of how to examine paranormal mysteries the way a scientist would. A “Try This” section encourages hands on thinking skills. For ages 10–15 years.

ORDER the paperback

Test Your Science IQ

by Charles Cazeau $20.00

Using a question-and-answer format that is fun to read and easy to understand, Dr Charles Cazeau takes you through more than 450 of the most intriguing science questions, from the profound to the amusingly trivial, overing both science and pseudoscience. Clear, well written, yet sophisticated enough for adults. Very strong on why science is important. The perfect book for the junior skeptic in your family which will teach how science works and why it is so important to understanding the world. Fascinating and fun. For ages 12 to adult.

ORDER the paperback

By Michael Shermer

The Believing Brain

by Michael Shermer $15.99

In this, his magnum opus, Dr. Michael Shermer presents his comprehensive theory on how beliefs are born, formed, nourished, reinforced, challenged, changed, and extinguished. We form our beliefs for a variety of subjective, personal, emotional, and psychological reasons in the context of environments created by family, friends, colleagues, culture, and society at large; after forming our beliefs we then defend, justify, and rationalize them with a host of intellectual reasons, cogent arguments, and rational explanations. Beliefs come first, explanations for beliefs follow.

ORDER the paperback

ORDER the harback

ORDER the unabridged audio CD

Science Friction

by Michael Shermer $10.00

Shermer pretends to be a psychic for a day…and fools everyone; as a psychologist and bicycle racer, he reveals the science behind sports psychology; as a historian and evolutionary theorist he considers what was truly responsible for the mutiny on the Bounty; and as a son, he explores the possibilities of alternative and experimental medicine for his cancer-ravaged mother. And as a skeptic, he turns the skeptical lens onto science itself. In each of the essays, he explores the very personal barriers and biases that plague and propel science, especially when scientists push against the unknown.

ORDER the hardback

ORDER the unabridged audio CD

On Religion & Society

The Bible Against Itself

by Randel Helms $7.98

Before the Bible was the Bible it was a lot of little books written by many writers with many different viewpoints. With depth and clarity Dr. Helms shows that, throughout the history of their formation, the Jewish and Christian scriptures developed as the by-products of ongoing theological debates. Far from expressing the unity of thought and doctrinal accord that would reflect divine inspiration, the scriptures represent a series of furious and unrelenting disputes between authors supporting often bitterly divided dogmas.

ORDER the paperback

ORDER the hardcover

ORDER the lecture on DVD

Collapse: How Societies Choose To Fail Or Succeed

by Jared Diamond $17.00

What caused some of the great civilizations of the past to collapse into ruin, and what can we learn from their fates? The Pulitzer Prize-winner traces the fundamental patterns of social catastrophe and physical collapse to a combination of environmental degradation, resource depletion, draughts, political upheaval, economic disaster, and war. Diamond employs the comparison method to test his hypotheses about the history of civilization, comparing different collapses at different times in different places around the world.

ORDER the paperback

ORDER the lecture on DVD

The Particle at the End of the Universe:

How the Hunt for the Higgs Boson Leads Us

to the Edge of a New World

How the Hunt for the Higgs Boson Leads Us

to the Edge of a New World

Scientists have just announced an historic discovery on a par with the splitting of the atom: the Higgs boson. The key to understanding why mass exists has been found. In The Particle at the End of the Universe, Caltech physicist and acclaimed writer Sean Carroll takes you behind the scenes of the Large Hadron Collider at CERN to meet the scientists and explain this landmark event. What is so special about the Higgs boson? We didn’t really know for sure if anything at the subatomic level had any mass at all until we found it. The fact is, while we have now essentially solved the mass puzzle, there are things we didn’t predict and possibilities we haven’t yet dreamed. A doorway is opening into the mind boggling, somewhat frightening world of dark matter. We only discovered the electron just over a hundred years ago and considering where that took us—from nuclear energy to quantum computing—the inventions that will result from the Higgs discovery will be world-changing.

TAGS: Higgs boson, physics, universe12-11-14

Celebrating 20 Years

of the Skeptics Society & Skeptic magazine

THANK YOU for over two decades of your continued support. We couldn’t have done it without you! We’re geared up and energized for the next 20 years and we hope you will support us in our mission of promoting science and skepticism.

We started Skeptic magazine in the garage of Michael Shermer’s home with volume 1, number 1, a tribute to Isaac Asimov. By volume 1, number 3, we were in a few isolated bookstores. By volume 2, we were being carried by hundreds of bookstores, and by volume 4, it was available in thousands of retail outlets.

We’ve reached over 100 million people,

and there’s more work to be done

We estimate that your support has helped our Executive Director, Dr. Michael Shermer, reach approximately 100 million people in 20 years of skeptical outreach through the 50,000 readers of Skeptic magazine each quarter, the nearly one million readers of his Scientific American column each month, the several million readers of his dozen books, the tens of thousands of people who follow our social media sources and YouTube channel, the tens of millions of viewers of his countless appearances on talk shows and television series such as The Colbert Report, 20/20, Dateline, Charlie Rose, Larry King Live, Oprah, Tom Snyder, Donahue, Lezza, Unsolved Mysteries, and other shows as a skeptic of weird and extraordinary claims, as well as interviews in countless documentaries aired on PBS, A&E, Discovery, The History Channel, The Science Channel, The Learning Channel, and on the 13-hour Family Channel television series, Exploring the Unknown, for which Dr. Shermer co-hosted. In addition there have been hundreds of opinion editorials in major newspapers, science reviews in national publications, university and college lectures and countless radio interviews, and millions of visitors and page views on skeptic.com.

Michael Shermer, in grad school in 1977, recalled Carl Sagan’s words of wisdom about the importance of science education. Those words were the candle in the dark that guided him for 15 years until he formed the Skeptics Society in 1992.

A Note from Michael Shermer

Executive Director of Your Skeptics Society

I cannot believe that it’s been 20 years since we founded the Skeptics Society and Skeptic magazine in 1992. It seems like only yesterday I was teaching at Occidental College and gearing up for a comfortable life in academia. Then I remembered something Carl Sagan said at a lecture I attended: “We live in a society exquisitely dependent on science and technology, in which hardly anyone knows anything about science and technology.”

It was a clarion call to me to forego a life of comfortable security as a college professor and venture into the business of being a public intellectual and expand the size of my classroom to the world. If you want to change the world you have to reach a lot of people—not a few hundred students, but a few hundred million people. I recalled that years before, when I was a graduate student in psychology when Uri Geller was all the rage, thinking maybe there was something to psychic power and ESP. But then I saw James “The Amazing” Randi on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show, duplicating all of Geller’s feats with simple sleight of hand. I suddenly realized that it’s not enough to be trained in science; you have to understand skepticism as it is practiced by professionals like Randi, who serve as a consumer advocate for rational thinking.

The best way to reach the wider public is through the popular media—magazine publishing (Skeptic magazine and my monthly column in Scientific American), books (from Why People Believe Weird Things to The Believing Brain—I’ve written 12 now), newspapers (I write regular opinion editorials and book reviews for the Los Angeles Times, Wall Street Journal, Science, Nature, and many others), radio and television interviews and talk shows, YouTube videos, blogging, Facebook, Twitter, and others.

If you have appreciated 20 years of the Skeptics Society and would like to see us continue for another 20 years, please make a tax-deductible donation to your Skeptics Society now. We have some special donation premiums that you can enjoy along with the knowledge that you have helped make the world a more rational place to live.

Our science lectures have gone global

The Skeptics Society’s Distinguished Science Lecture Series at Caltech features top science writers lecturing on controversial and cutting edge science. We have now gone global by live streaming our lectures to anyone, anywhere in the world with an Internet connection. Now, instead of hundreds of people attending events, potentially millions can watch our lectures broadcast live from Caltech, thereby expanding the international reach of skepticism.

If you’ve ever seen our Executive Director Michael Shermer being interviewed on television, chances are you’ve seen the Skeptics Society’s office and library.

The media now asks for the

skeptical viewpoint by name

At the time we founded the Skeptics Society there was a great deal of debate about the wisdom of using the term “skeptic.” Was it too negative? Did it sound to much like “cynic”? There are basically three options when choosing a name: you can find something that means exactly and only what you want it to (not likely); you can invent a word and spend millions on advertising to define it, like corporations do (too expensive); or you can doggedly redefine an existing term to make it mean what you want it to mean.

We have had a great deal of success redefining “skeptic” with the later strategy. One of the great frustrations when being interviewed by the media is trying to convince producers that the reality behind the myths and the reasons for critical thinking errors are just as interesting as the fantastic claims. They admit they know the psychic, bigfoot, or ancient alien stuff is bunk, but argue that it is what the public wants.

But we’ve noticed a change after 20 years. Now calls from the media usually start with the explanation, “We want to get the skeptical viewpoint.” If you’ve ever donated to the Skeptics Society you can take a bow for lighting this little candle in the dark. The idea that evidence, common sense and rational analysis should be sought out when presenting an extraordinary claim to the public is slowly taking root.

Skepticism is hitting the mainstream

There are other indications that “Skeptics” have become a part of the larger culture. We first noticed cartoons popping up in the national media featuring gags about a “Skeptics Club,” a “National Society of Skeptics,” or a “Skeptics Headquarters.” We began to get requests to use Skeptic magazine as set dressing on TV and movie sets. This fall an ABC TV conspiracy series will star an “expert on debunking the supernatural who writes a regular column in Scientific American, and who has spent “20 years as the editor of a skeptic magazine.” (Coincidence? You decide!) You know you’ve really made a dent in the public consciousness when a skeptic journalist/investigator (again, who writes a regular column in Scientific American) is featured as the hero in a romance novel—written by best selling author Nicholas Sparks, no less! Rumor has it that the screen play adaption has been sold. We breathlessly await the casting call.

We continue to educate Junior Skeptics—

our hope for the future!

Junior Skeptic magazine, bound within every issue of Skeptic magazine, is the skeptical movement’s most sustained and substantial educational outreach project for children— and it needs your support. With its clarity, focus, and commitment to in-depth research on classic paranormal mysteries, its content speaks to the heart of scientific skepticism. Help share that rare and beautiful tradition with a new generation of skeptics.

Junior Skeptic does more than teach the knowledge of the past. It regularly breaks new ground with original research—expanding and refining the skeptical literature, teaching the methods of skeptical investigation, and breaking cold cases wide open.

We’re proud to be recognized for the

quality and depth of our work

Hailed as a “tour-de-force of science writing,” the quality and depth of Junior Skeptic material was recognized in 2010 and 2011 with multiple award nominations for Daniel Loxton’s children’s book Evolution: How We and All Living Things Came to Be, based upon Junior Skeptic material. We thank Skeptics Society donors whose support helped to bring that vitally important educational content into the world.

We keep science at your fingertips

with our magazine and podcast apps

Get our official podcasts apps for Skepticality and MonsterTalk and enjoy your science fix and engaging interviews on the go!

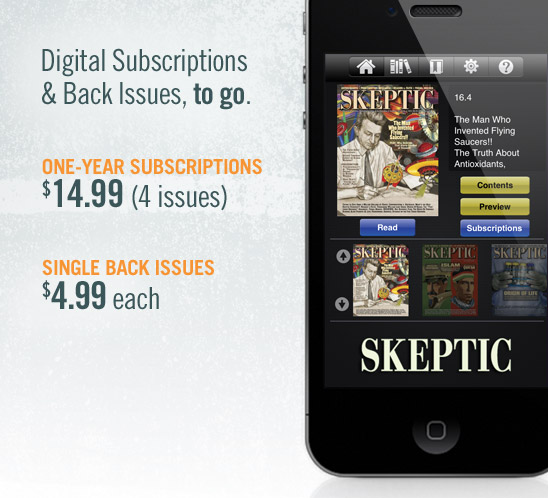

Our newest addition launched last week—The Skeptic Magazine App—brings digital subscriptions and back issues to your iPad, iPhone, iPod Touch, Android smartphone or tablet, PC, Mac, Kindle Fire, Kindle Fire HD, and BlackBerry PlayBook. Download the free app and explore your favourite magazine like never before, wherever you happen to be! It comes with a free 44-page Preview Issue!

We promote thinking like scientists

Skepticism 101: The Skeptical Studies Curriculum Resource Center is one of the most important projects we’ve ever launched. Students are the decision makers of tomorrow. Evaluating extraordinary claims, and understanding the scientific method should be part of every classroom experience. Last year’s highly successful fundraising campaign enabled us to develop webpages which now offer course syllabi, reading lists, articles, essays, lectures, PowerPoint/Keynote presentations, YouTube videos, book recommendations, as well as educational and entertaining demonstrations that illustrate key points of skeptical thinking for students, teachers, and anyone interested in science to use and share. The enthusiastic response by thousands of educators to our initial offerings indicate that this a valuable resource that deserves your support. The Skeptical Studies Curriculum Resource Center is just the latest in our 20 year campaign to make the world a better place through science, reason, and skepticism. If you teach a skepticism class and have curriculum materials you would like to share, please contact us to contribute.

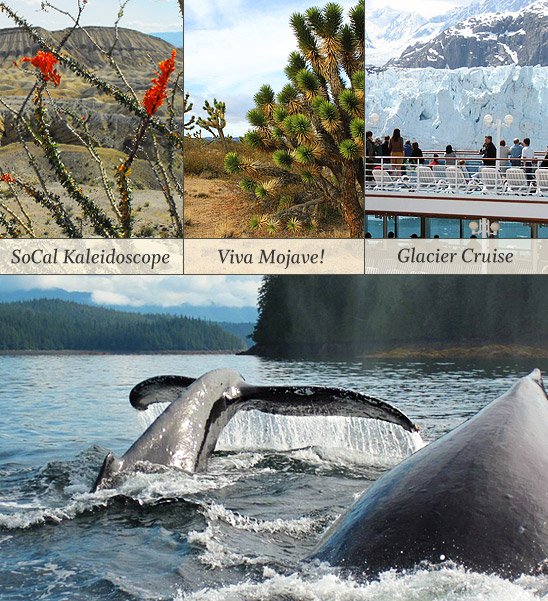

Whales dive next to an excursion zodiac on our Alaskan Glacier Cruise. No telephoto lens was used to take this spectacular photo!

Geology tour fundraisers

While much of our mission deals with pseudoscience, our supporters are passionate about science itself. Our famous geology tours are fundraisers that provide an opportunity for members to enjoy top notch geology lectures and spectacular scenery in the company of other science enthusiasts. Sign up for priority notice of future geology tours and we’ll let you know by email in advance.

We’re in this together.

We need your support.

Make the world a more rational place and defend the role of science in society. Please make a tax deductible donation now…

12-11-07

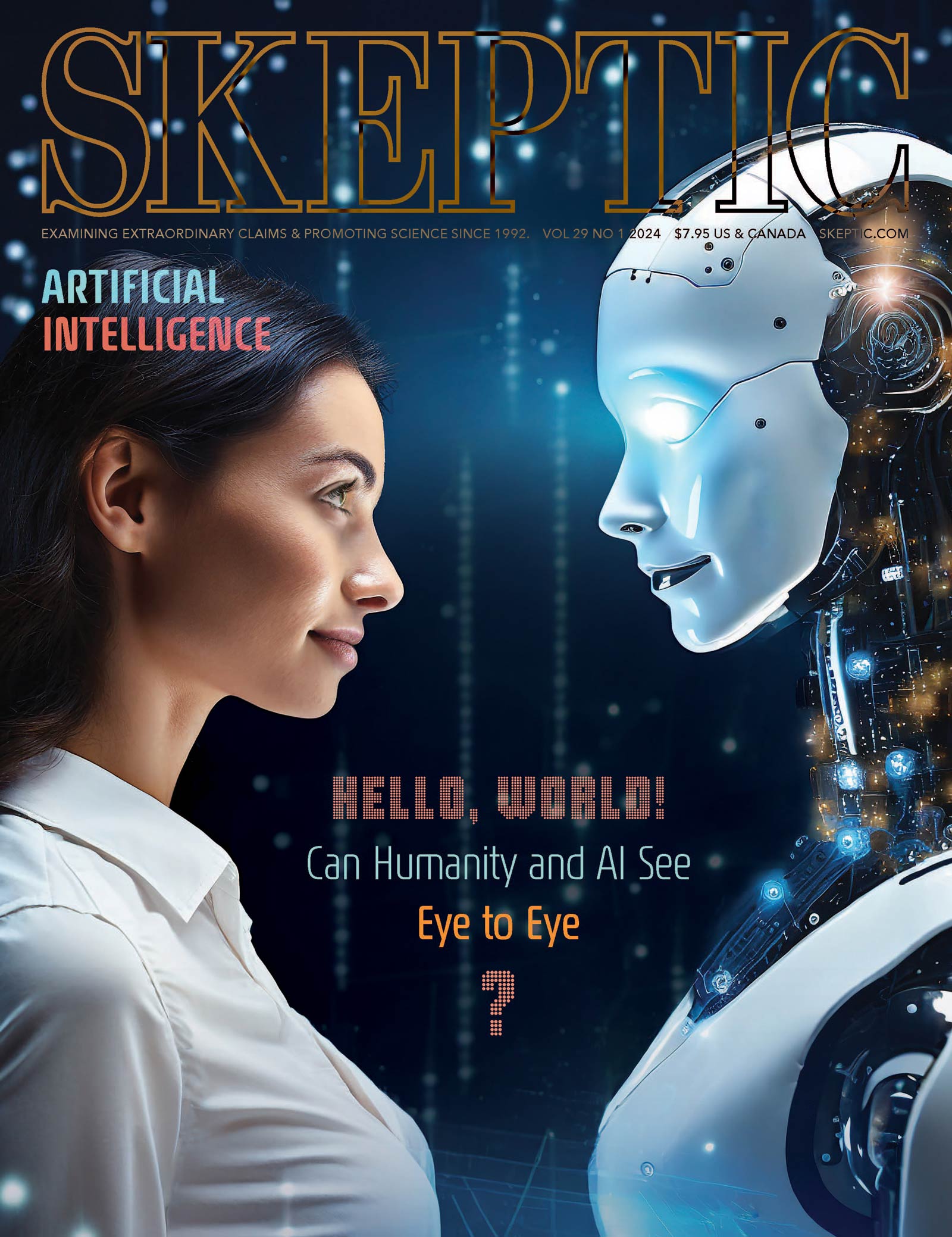

Introducing the Skeptic Magazine App

Some things are worth waiting for, and we think you’ll agree that this is the best thing to happen to the magazine since we started printing it 20 years ago.

Your Favorite Magazine

Like Never Before!

Enjoy your favorite magazine like never before! Get the FREE Skeptic Magazine App and enjoy digital subscriptions and back issues on the go. One-year digital subscriptions are $14.99 US (4 issues). Single back issues are $4.99 US each.

Fits in your pocket and on your PC

iPad, iPhone, iPod Touch, Android smartphone or tablet, PC, Mac, Kindle Fire, or BlackBerry PlayBook—we’ve got you covered! The Skeptic Magazine App goes where you go.

Happiness is …

Getting the Latest Issue Instantly!

Forget about waiting for the magazine to arrive at your door. Digital subscribers enjoy the latest issue of the magazine before it even leaves the presses!

Download the app for free.

Get the Preview Issue for free!

Download the FREE Skeptic Magazine App and enjoy the free 44-page Preview Issue.

Download to your Apple (iOS) device

Download to your Android device

Download to your Kindle Fire

For Kindle Fire users within the United States, United Kingdom, France, Italy, Germany, and Spain, download the branded Skeptic Magazine App from the Amazon Appstore. Kindle Fire users within the UK can also simply launch the Newsstand and search for “Skeptic” to download the app.

For Kindle Fire users outside the US, UK, France, Italy, Germany, and Spain (or if the above instructions do not work on your Kindle Fire) please follow these alternate directions to install the PocketMags App directly onto your device. Once the PocketMags App is installed on your device, search for “Skeptic” within the app.

Download to your BlackBerry PlayBook

For BlackBerry PlayBook users, the digital version of Skeptic magazine is available within the PocketMags App. Once the PocketMags App is installed on your device, search for “Skeptic” within the app. Download the PocketMags App from the BlackBerry App World.

Download to your PC or Mac

For those of you who don’t have a smartphone or tablet device, you can still subscribe to the digital version of Skeptic magazine and purchase individual back issues on your PC or Mac via PocketMags.com.

NOTE: PocketMags.com is based in the United Kingdom and prices for digital subscriptions and single back issues are shown in British Pounds.

For more information, visit skeptic.com/magazine/app

12-10-31

In this week’s eSkeptic:

The Science of Sociopaths

The Wisdom of Psychopaths: What Saints, Spies, and Serial Killers Can Teach Us About Success

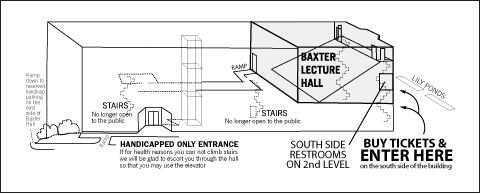

RECORDED LIVE: Sunday, October 28, 2012

Baxter Lecture Hall, Caltech

Rent this lecture on Vimeo On Demand

Watch Dr. Sean M. Carroll for free online,

broadcast live from Caltech!

New Admission Policy and Prices

Please note there are important policy and pricing changes for this season of lectures at Caltech. Please review these changes now.

SINCE 1992, the Skeptics Society has sponsored the Skeptics Distinguished Science Lecture Series at Caltech: a monthly lecture series at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, CA. Most lectures are available for purchase in audio & video formats. Watch several of our lectures for free online. Our next lecture is…

The Particle at the End of the Universe: How the Hunt for the Higgs Boson Leads Us to the Edge of a New World

Sunday, November 18, 2012 at 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

Scientists have just announced an historic discovery on a par with the splitting of the atom: the Higgs boson. The key to understanding why mass exists has been found. In The Particle at the End of the Universe, Caltech physicist and acclaimed writer Sean Carroll takes you behind the scenes of the Large Hadron Collider at CERN to meet the scientists and explain this landmark event. What is so special about the Higgs boson? We didn’t really know for sure if anything at the subatomic level had any mass at all until we found it. The fact is, while we have now essentially solved the mass puzzle, there are things we didn’t predict and possibilities we haven’t yet dreamed. A doorway is opening into the mind boggling, somewhat frightening world of dark matter. We only discovered the electron just over a hundred years ago and considering where that took us—from nuclear energy to quantum computing—the inventions that will result from the Higgs discovery will be world-changing. Order the book from Amazon.

Followed by…

- DR. DONALD YEOMANS

Near-Earth Objects: Finding Them Before They Find Us

Sunday, December 2, 2012 at 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

A Good Death: Interview with Caitlin Doughty

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 194

It is All Hallows’ Eve once again, the time of year when all things creepy and terrifying seem to be highlighted. This week on Skepticality, Derek embrace the time of year in this interview with mortician Caitlin Doughty, from Los Angeles, California who attempts to educate society about the reality and science of death, and hopefully remove some of fear and uncomfortable feelings that are associated with it.

Get the Skepticality Podcast App

for Apple and Android Devices!

Get the Skepticality App — the Official Podcast App of Skeptic Magazine and the Skeptics Society, so you can enjoy your science fix and engaging interviews on the go! Available for Android, iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch. Skepticality was the 2007 Parsec Award winner for Best “Speculative Fiction News” Podcast.

The Latest Episode of Mr. Deity: Mr. Deity and The New Testament

WATCH THIS EPISODE | DONATE | NEWSLETTER | FACEBOOK | MrDeity.com

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, Apurva Narechania takes an inside look at how astronomers are searching for extrasolar planets. This article was published this year in Skeptic magazine (17.3).

Inside the dome at Mt. Palomar (photo copyright Ben Oppenheimer, used with permission)

The Glare of Other Suns

An inside look at how astronomers

are searching for extrasolar planets

by Apurva Narechania

The main road on Palomar Mountain ends at a cottage called the Monastery. The Monastery houses sleeping astronomers during the day so they can look into the sky at night. Opening a Monastery blackout shade in midday is like emerging from a matinée. The light of Southern California hurts when training to bear the night.

At around 4 pm on a clear day in December, I rolled out of bed to eat an early dinner prepared by Dipali Crosse, an earnest woman who makes tasty food from the kind of enormous boxes and cans that weigh down the shelves at Costco. Her food is fit for lumberjacks. This is our one good meal of the day. At the oak table, astronomers are already sitting shoulder to shoulder, some chairs angled around inconvenient corners. The Monastery has 12 rooms. On a normal observing run, only a few are occupied. But this week, the place is full. A few even had to shack up at the reservation casino a couple thousand feet down Palomar Mountain. Everyone is in town to see planets. Around stars hundreds of light years away, we now know there are other worlds. But they are impossibly faint, ghosts around the already dim suns that sustain them. On this trip, the light of those stars will be collected and then pared to find the planets in their orbit.

I had first seen the instrument that does the paring at Ben Oppenheimer’s lab at the American Museum of Natural History (I also work at the AMNH as a biologist in the Genomics Department). Oppenheimer is an astrophysicist and his is one of only three ground-based systems designed to visualize extrasolar planets. With its cover off nearly 19 optical surfaces sat exposed, each beaming light to another, and ultimately to a coronograph, a device that functions as an occulter, and is at the heart of any astronomical instrument designed to see things other than stars. Oppenheimer and his colleagues have been working on this instrument for nearly six years. Dubbed Project 1640, the technology uses adaptive optics to calm the distortions inflicted by atmospheric turbulence, and speckle suppression to dampen the residual diffractive light that remains from the star even after it has been occulted. Twentythree computers automate the synergy of nearly 4,000 movable parts. On a five night observing run on the 200-inch Hale telescope—the largest at Palomar and one of the largest in the world—the detector will collect 500GB of data. But most of the data, most of the light, is useless. The instrument must cut through the glare of the nighttime sky to image shy planets. Light from a star saturates its satellites. The starlight itself is extraneous, annoying even. “Once you’ve taken the best picture your technology will allow,” said Oppenheimer, “you have to delete it.” One photon in ten million comes from the world Oppenheimer most wants to see. It’s like staring into the light of a thousand suns or searching for Venus at noon. Oppenheimer deletes his way to clarity.

We end dinner with obscene amounts of coffee, and head to the telescope at dusk. Sasha Hinkley, a postdoc in astrophysics at Caltech and one of Oppenheimer’s former students, is already there, suspended from the end of the telescope in the Cassegrain cage. The cage is a metal enclosure that cradles the fivemeter mirror, forming a giant cup with access to the Hale’s key optics and Project 1640’s instrument. The telescope dwarfs the cage. It rises nearly 13 stories wrapped in a white dome of precious steel borrowed from the industrial machine of WWII America. On the outside about three quarters of the way up, a catwalk skirts the dome and moves as the telescope slews so that astronomers catching a quick smoke might see the lights of Temecula give way to the steady glow of LA County without lifting a foot. The dome is otherworldly whether you’re in it, on it, or looking at it in full moonlight as I did on my first night. Against the dark sky it stands in blanched relief, a functional monument, every part of its interior and exterior curvature accessible and working. Climbing around the telescope, I realized how reassuring corners are. There are no right angles at Palomar. The dome, the mirror, the ingenuity of out-of-the-box people past and present: it’s a giant bowl of light and thought.

I climbed into the cage with Hinkley a fraction of a second after being invited. The telescope was parked, its mirror facing straight up and its body at a right angle to the ground. We were resting on our backs against the cage’s metal, suspended a dozen feet above the ground. Around us in the semi-darkness, cables spilled out of instruments like vines from a metal canopy. Almost immediately above us, the primary mirror lies in its steel bed and the telescope extends as if from our bellies, hundreds of feet up. The mirror is a monolithic piece of glass polished to near flatness, never deviating more than two millionths of an inch. It pivots on a horseshoe mount and glides along oil pads so frictionless that a 1.5 horsepower motor turns its vast bulk. If you’re alone in the dome at night while the telescope slews, it can feel like sharing a cave with a careful giant. Though the Hale telescope has been called the Big Eye, nobody looks directly at the light it collects. A few stories up, towards the crowning secondary mirror, there is a snug, one-man compartment with controls like the cockpit of an old fighter. Its single leather seat is cracked and the spongy cushion cratered. Astronomers used to sit there alone, at prime focus, looking into the galaxy though an eyepiece. Now the Big Eye directs all its light to the instruments that hang above us, open, with their delicate optics exposed. After an hour against the cage, its pattern was etched into our skin even through sweaters and jackets.

Hinkley was trying to focus the instrument using an artificial white light source, moving mirrors and lenses back and forth a few microns at a time. He would tighten a bolt with a twenty-degree turn of an Allen wrench and Oppenheimer would yell at him for going the wrong way or not going far enough. “You ever try to put a Christmas tree up with your wife?” asked Hinkley. His voice went up a register. “‘Rotate it’, she says. ‘Which way? Clockwise. No, wait, counter-clockwise. Don’t put that ornament there! What are you doing?’ ” A wrench in his mouth and another in his hands, he said, “Well this is kind of like that.” The work put the notion of manual focus in entirely new perspective. Modern astronomy is as much about instrumentation as observation, as much an engineer’s field as a scientist’s. “In our engineering, we do things just well enough. Out here things are never going to be perfect,” said Oppenheimer. Observational astronomers are mechanics. No one else could know how to fix their singular machines. “Ben, do you want to come out here and take a look?” asked Hinkley. “In astronomy we have to build this stuff from scratch.”

Oppenheimer joined us. He found a tight spot and squatted in a pile of cable that had collected in the cage. The adaptive optics system alone has nearly 600 pounds of the stuff, snaking around your ankles, coiled against most of the walls. “Cable management if done properly can save you many days of sitting on your ass undoing other people’s knots,” said Oppenheimer, twisting a nut. “I think that should do it. Let’s go check.” As we climbed down the ladder to head into the control room, he caught sight of his knuckles. They were bleeding. In the dry mountain air, most people slough their skin and shrivel, but Oppenheimer, his hands constantly in tight spaces threading metal edges, bleeds. “You bleed into these things. You put your life into them. Look at my knuckle. I don’t know how that happened.”

***

51 Pegasi B was the first exoplanet discovered around a main sequence star. Before its announcement, exoplanetary science was an astronomical backwater. Cosmology, with its emphasis on the origins of the universe, its boundaries and the constancy of its physical laws, still dominated astrophysical research. 51 Pegasi B brought exoplanets into focus. It’s enormous, nearly 150 times the size of the Earth, about half the size of Jupiter. But unlike Jupiter, 51 Pegasi B orbits its star at distances that would set your hair on fire. Imagine a planet of that size whipping around the sun inside the orbit of Mercury. 51 Pegasi B screams around its star completing one full orbit in four careening days. It’s a Hot Jupiter: a gaseous planet with a scalding surface. Its period of rotation mirrors its period of revolution, so only one side faces its star, an arrangement astronomers call tidal locking or synchronous rotation. Some artists’ renditions situate the planet at the flaring edge of its star’s corona: a giant world of baked gas unfurling in its speed. Prior to its discovery, most theorists thought that gaseous planets could exist only in the farthest orbits of stars. 51 Pegasi B probably did form in the further reaches, but then migrated inward, stopping just short of falling into its sun. In 1995, when 51 Pegasi B was discovered, the only planets known were those in our solar system, where gas giants operate in distant orbits. 51 Pegasi B turned planetary science on its head.

The last ten years of exoplanetary study have outstripped any narrative. There are planets believed to be the consistency of Styrofoam, ocean worlds with nitrogenous atmospheres, carbonaceous planets that might be studded with diamonds. Planets that circle two suns, and rogue planets presumably flung from their parent stars to wander the galaxy alone. And we are on the cusp of detecting planets that sit in their star’s habitable zone where liquid water and a shielding atmosphere coexist to perhaps nest extraterrestrial organics. Science like this buries science fiction. When 51 Pegasi B was first discovered, it inspired a renewed wave of thinking about our place in the universe. Exoplanetary science was clearly no longer the soft pocket of astrophysics, filled with careless futurists and their philosophers. It was real. If there are planets and we can detect these planets, how many are there and are there others with Earth’s chemistry? The notion of life elsewhere went from whimsy to hypothesis. SETI, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, garnered a bit more cachet. NASA formalized its Astrobiology program. Astronomers dedicated more telescope time to the search for giant planets. A Time magazine cover ran with the headline, “Is Anybody Out There?” For science and astronomy magazines, the question is a trope that never fails to pique its core, warp-powered audience. But because there was finally data, young scientists were listening. Oppenheimer’s early work as a graduate student at Caltech was juiced by these discoveries. 51 Pegasi B was remarkable not because it existed, but because it was so exotic, so unexpected in its size, composition, and proximity to its star. Theorists build models on what they know, but space is vast and the configurations of things unseen are manifold. We just don’t know what to expect. So why not expect life to be out there? And why not look for it?

51 Pegasi B is located only fifty-one light years from Earth, a next-door neighbor. In comparison, the Milky Way is 100,000 light years in diameter. The light we now see from its opposite edge was first emitted as modern humans were leaving Africa. That’s old light, but at least we have a chance to see it. The universe is large on another scale altogether. Light from events in its past may never reach us. Astronomers call this the past horizon, a limit on the most distant objects we can see. In the same way, light from us may never reach its outer rim. This is called the future horizon. Bound by horizons past and future, we occupy a corner of the universe we can observe and affect, and there are things about it we can never know. But it’s this sense of vastness that is most compelling to exoplanetary scientists. The universe is likely filled with as many if not more planets than stars. And because planets are cool and exist at various distances from their suns, their chemistries are more complex. If you know a star’s mass and composition, you can predict its lifespan and its life’s work. Planets are the dark horses of the universe. Its art resides within them. The question is, just how creative has the universe been?

***

I first met Ben Oppenheimer at his office in AMNH. He sat at a neat desk in front of a wall bathed in bluish-purple light, as if peeking out from a nebula. I introduced myself as a fellow scientist completely naïve to astronomy, but fascinated by early life on this planet and the possibility of life on others. Try making this admission in an astrophysicist’s office. I knew that Oppenheimer was a new breed of astrophysicist who no longer thinks exoplanetary science and habitability is fantasy. But it’s still hard to shake the self-consciousness inherent in legitimizing your Sci-Fi childhood. I timidly suggested that any article on his work should deal with the search for habitable planets. I must have sounded apologetic because he looked amused. “I think the issue of life is, in the end, where this is all going. It has to. I think people want to know. If there is an earthlike planet out there, what is it like?” His eyes flickered beneath stylishly framed glasses. I asked him if we could ever hope to perceive, let alone conceive, life as we don’t know it. “It’s important to keep the parameter space for whatever you’re doing as open as you can,” he said. Translation: I have no idea, but be openminded and prepared. “I think this is one of the deepest philosophical questions people have had for ages. Is there anything else out there?”

But what do you look for? How do you start? At a glance, through any telescope, 51 Pegasi B and its star, 51 Pegasi are a single body. The planet is in so close an orbit that its own light is blanched. But you can still infer its existence. Almost every exoplanet discovered so far has been detected through inference. 51 Pegasi B exerts a gravitational effect on 51 Pegasi causing the star to either inch toward or away from an observer. This quiver is detectable as shifts in the color of the star’s light. The effect is Doppler in nature. An approaching object either shines or sounds with quickening frequency. That same object’s frequency abates as it recedes. The technique is called radial velocity: the change in velocity of the star given its planet’s gravitational influence. Jupiter causes a 12.7 m/s change in the sun’s radial velocity. 51 Pegasi B clocked in at 70 m/s. Earth causes a 9 cm change, a number that puts into perspective our galactic insignificance.

But Oppenheimer believes that inference is not enough. The problem with inferential techniques like radial velocity is that they are information poor. You can get a sense of the mass of a planet and its orbit, but if you can’t see it, if you can’t gather any light from it, you are blind to its true nature. Still, inferential techniques are mature and proven. Radial velocity is only one in an arsenal of inferential methods. The fabulously successful Kepler mission has uncovered more planets in the last year than had ever been detected before. So far, 2300 planet candidates have accumulated in its three years of operation. Kepler is a space-based telescope tasked with staring at the same set of 100,000 stars for seven and a half years. If a solar system is arrayed edgewise with respect to Kepler, any planets that cross in front of the system’s star would register as diminished starlight. Like the radial velocity technique, the change is beyond subtle. A typical planet might reduce the light of its star by 1 to 10 parts in a million. Signals are so faint, and the opportunities for observation so erratic and evanescent, even firm observations are never infallible. An Earth-like planet would produce this weak signature once a year. Kepler requires at least three such passes before elevating the observation to a planet candidate. If a given star’s dimming is due to a planet, the change will be periodic, revealing size and trajectory. But many of the finer details of the planet remain a mystery.

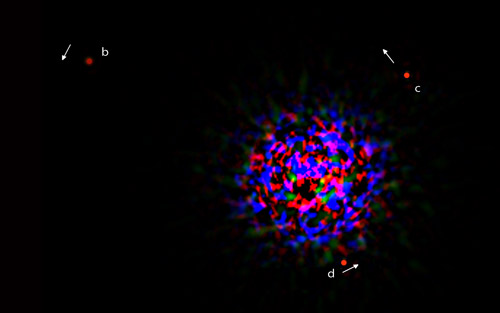

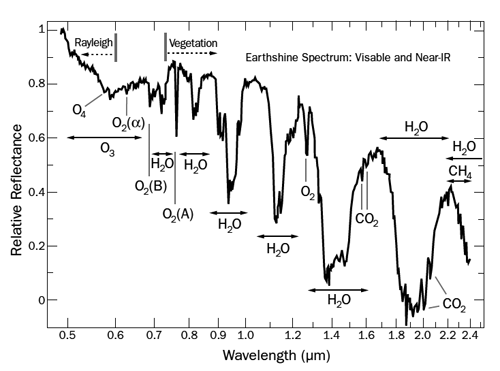

Figure 1: Three large planets (b, d, and c) around the star HR 8799. (Science. November 28th 2008. Volume 322, Page 1348.)

Exactly thirteen years after the existence of 51 Pegasi B was published, a new technique called direct observation yielded its first success: three large planets around the star HR 8799. Direct observation dispenses with inferential data. Instead, light from planets is separated from the star and concentrated with long exposures. The known system is shown in Figure 1 (to the right).

In this image, the planets are nearly 100,000 times fainter than the star. Without starlight suppression, the entire frame would render as a block of impenetrable light. The remnants of the star are visible as a collection of iridescent speckles, and around this ball of muted light orbit three small, red dots: HR 8799 b, c and d. Speckles are such a notorious problem in optics of this kind that a whole subfield has been spawned to invent ways to contain them. Fortunately, HR8799 has a giant solar system with distant planets that aren’t consumed by the speckles. Our own system would sit squarely within the cluster. Neptune is about as far out as HR8799 d. The most distant planet in the HR 8799 system is 68 astronomical units away from its star, or 68 times the distance of the Earth from our Sun. It takes 450 years to complete one orbit.

HR8799 is a young star. It’s so young that its visible planets are still hot and generate their own light. Earth-based direct observation can only detect hot planets. The imaging technology is not yet capable of detecting reflected light. It’s too faint. But a spacebased telescope could do the job. In May of 2002 NASA funded a feasibility study for the Terrestrial Planet Finder (TPF), a proposed orbital telescope devoted to planetary imaging and the cancellation of starlight. The TPF’s angular resolution would make detecting a Jupiter-like planet a cinch and an Earthsized planet a genuine possibility. In 2004, the TPF’s architecture was approved for construction at a cost that engineers estimated at $10 billion. By 2009, after the dramatic depths of the recession had worked its way through the budget, NASA’s share had shriveled and the TPF’s completed schematics were bound and shelved, a worked but unrealized solution. Oppenheimer has no patience for the government’s misallocation. “NASA’s budget in the scheme of things is ridiculous. It’s like a drop in the bucket. We could choose to do so much more, but we don’t,” said Oppenheimer. “If you want to understand the Earth, you need something to compare it to.”

HR8799’s currently visible planets could never sustain Earth-type life. But rocky worlds in its habitable zone may be buried in the morass of speckles. While transiting and radial velocity excel at the detection of Hot Jupiters and planetary bodies close in on their stars, ground-based direct observation is limited to the detection of gas giants at glacial distances. Coronography has succeeded in making the light of distant planets accessible, but starlight is a pesky thing. It diffracts around the optical stop, it leaves ghosts of its deleted self. The speckles can be dimmed but never removed. The exoplanetary sweet spot, the habitable zone, a narrow ring around each star, is ironically the most elusive band for detection of any kind.

The technical challenge is immense. Project 1640 consists of four homegrown instruments that relay light from the sky to a computer screen. The optics are so complex that only 10% of the non-occulted, impinging light survives the process. First, the adaptive optics system compensates for the atmosphere. The coronograph then tempers the target star’s light. An integral field spectrograph, which Oppenheimer simply calls the science camera, records 30 images of the star across 30 different colors simultaneously. A calibration wavefront sensor (CAL) measures and compensates for the defects in the optics. Images from the science camera are stacked, one slice per color. Oppenheimer calls this 3D image The Cube. It’s not three-dimensional in space. The image of the star is flat. Here, depth is devoted to color. The location of a speckle is dependent on the color observed. If you trace a single speckle through the cube, you’ll notice that it radiates out from the star’s center. The cube is the star’s pop-up book, telling its story in three dimensions with slices through the electromagnetic spectrum. The images are beautiful when animated, as if the star were a multi-chromatic geyser of its own occulted remnants. Planets are points of light that drill through the cube, motionless through every section as the speckles scatter.

Of all the instruments currently used at the Hale telescope, project 1640 is the most complex. In all, the project has one hundred nights of observing time. When the sun goes down, a clock starts ticking in Oppenheimer’s head. If it rains, if it’s cloudy, if the seeing is lost in swirls of misbehaving air, he goes home with nothing. There are no allowances for bad luck. The Monastery has a guest book where scientists and visitors can formalize their paeans to Palomar. When Oppenheimer signed this book four years ago, he did not mince his ambition with customary homage. Instead he wrote a declaration. “June 24th, 2008. Project 1640 has arrived from NYC. We shall see whether it works in short order.”

***

Three and a half years later, Tom Lockhart was sitting on the toilet seat in the control room’s bathroom. The temperature in the dome had dipped below freezing, unusually cold even for December on the mountain. Lockhart designs and runs the software controlling the CAL system. He wore a hat with earflaps and was warming a motherboard against the radiant coils of an old heater. “I don’t know. The thing just started beeping,” he said. Computer hardware fails when it’s hot. Everyone knows that. But the motherboard in the CAL started talking to Lockhart when it got too cold. “It slowed to a fraction of its normal speed and then told me it was shutting itself off. You ever hear of anything like that?”

The telescope was pointed at HR 8799. Oppenheimer wanted to see whether the new instrument could pick up known planets. “Can you people please clam down? Where’s Tom?” Oppenheimer asked.

“He’s in the bathroom having a good time with the CAL’s processor,” Gautam Vasisht said. Vasisht is the CAL’s hardware designer. He and Oppenheimer shared an office when they were graduate students at Caltech. Vasisht is the small, ironic subtext to Oppenheimer’s volubility. “So much for the romance of astronomy.”

“I feel like I’m doing the same thing over and over again. Like I’m in some kind of nightmare,” Oppenheimer said. Trouble with the CAL’s processor meant less time on sky. “In a way, it’s good there’s bad seeing.” The stars were translucent behind a high, thin sheet of clouds. “Where the fuck is Tom? Seriously. Is the CAL going to work? It might clear any second.”

The room was filled with physicists. Mike Shao, honored with the 2010 Michelson prize for his pioneering work on ground and space based interferometers, asked if there was a resistor lying around. “If we plug in a resistor and put it directly on the computer’s enclosure, would that heat it up enough?”

Shao’s suggestion was like asking an astronaut whether duct tape could hold together a splintering spacecraft (which worked for Apollo 13!). After years of engineering precision starlight control, in unanticipated cold, the resistor was the kind of kluge you have to dig deep for: high school physics rounding out the rough edges on Palomar Mountain.

“There might be something downstairs. Hold on,” said Kajsa Peffer, one of the telescope operators.

Lockhart stood up, turned off the bathroom heater, and closed the door behind him. Satisfied with the roasting he gave the CAL’s motherboard, he went into the dome to reinstall it. He took with him some duct tape and the resistor Kajsa had dug up from the spare parts room. Lockhart strapped the resistor to the instrument, and turned off the computer’s cooling fans, so the work of imaging other worlds could proceed

“We’ve tried to image this system eight times and the conditions have been bad every time,” said Oppenheimer. “Now the conditions are bad and all the instruments are screwed up. It’s like the aliens are trying to hide their planet from us.”

“Imaging exoplanets: an exercise in fucking futility,” said Vasisht.

“Seriously man. I hate this fucking star. We haven’t recorded a single science frame tonight. This star hates this project. Kajsa, how long can we stay on this piece of shit?” asked Oppenheimer of the telescope’s operator.

“Two hours.”

“Two more hours? Oh god. You people need to calm down.”

When you can get it, light from a planet is a rich source of information. A few collected photons can betray an entire atmosphere’s chemistry. Chemical species absorb particular frequencies of light leading to dips in reflectance along certain points in the spectrum. In 1961, James Lovelock, an independent scientist and inventor, was contracted by NASA to determine what could be seen from a planet’s light, from these spectra. Lovelock reasoned that if a planet were alive, its atmosphere would contain highly reactive compounds—oxygen, methane, hydrogen— at high concentrations despite their tendency to react with one another. From afar, a spectrum of our planet’s atmosphere would betray chemical disequilibrium. Oxygen and ozone cooccur with methane. Water vapor lubes the mix. On a dead planet, molecular oxygen and fully reduced carbon (like methane) would be unlikely to co-exist. Life keeps these biosignatures at high concentrations as raw material for our fundamental processes: respiration and growth.

We only know of one planet with life. With this in mind, Carl Sagan devised an experiment to peek at Earth from space. In the early 1990s, as the Galileo spacecraft swung around Earth in a gravitational shot towards Jupiter, Sagan turned its camera back towards our planet. In the paper describing this effort (Nature 365, 715–721, 21 October 1993), Sagan imagined the Earth was extraterrestrial, deriving “conclusions from Galileo data based on first principles alone. He found an “abundance of gaseous oxygen” and “atmospheric methane in extreme thermodynamic disequilibrium.” The spectrum also highlighted a “widely distributed surface pigment with a sharp absorption edge in the red part of the visible spectrum.” Chlorophyll: plants. Of course, the experiment was a conceit. The light Sagan collected, its luminosity and detail, is a pipe dream given the scraps Oppenheimer collects from other worlds. The question is what would Earth look like if you could only scavenge a few photons? What would it look like well beyond our solar system?

It turns out you can look back at the Earth, as if from deep space, while standing on your roof. Our planet is reflected back to us every night by the moon. During its crescent phase, the moon’s brilliant edge cradles an ashy wisp of the rest of its body. The crescent reflects the Sun while the darker whole reflects the Earth. This phenomenon is known as earthshine: our light returning to us from our moon. Because the moon is an imperfect reflector, the Earth’s light is homogenized, mimicking its appearance from great distances well beyond our solar system, even from neighboring stars. Earthshine is our best guess at what the light from a living, breathing planet might look like when viewed from other parts of the galaxy. Above is a picture of Earth from the moon, our proxy for light years away (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Measuring earthshine as reflected by the Moon is our best guess at what the light from a living, breathing planet might look like. (Redrawn from The Astrophysical Journal, Volume 644, Issue 1, pp. 551–559.)

This is a spectrum. The x-axis plots a narrow section of wavelengths in the visible and near infrared. The y-axis is an index of reflectivity: lower reflectivity at a given wavelength implies an absorbing entity, a molecule cutting into the light. The signatures of life on this planet are coded into the peaks and dips of this graph: the oxygen respired by animals, the carbon dioxide absorbed by plants, the methane emitted from geological activity like volcanoes and biological activity like flatulent cows, the ozone that protects DNA from ultraviolet radiation, the water that supplies electrons for building complex sugars in plants, and the signature of pigments used by the light-harvesting biomolecular machines that energize this planet. A living planet’s vitality informs its chemical constituency and life is dissolved into an atmosphere of its own creation. This thin shell of gas is a message from the planet; light can signal whether it’s alive or dead. Pictures like these are what Oppenheimer and the Project 1640 crew want from faraway worlds. But the spectra will be fingerprints, detailed, distinct. If it exists, life elsewhere will likely be very different, but still optically and chemically accessible.

The CAL’s processor was back up and only one hour remained before HR8799 would set. Now that everything was finally working, the stars hid behind a new set of thin clouds. “Of course that would happen,” Oppenheimer said. “It’s like we can’t win with this crap. Why don’t we do something easy like banking? We’d make a lot more money.”

“In Monopoly, my daughter’s realized that if she’s the banker, she always wins,” Vasisht said.

“If I wanted to make money then I wouldn’t be here,” said Douglass Brenner, a programmer, physicist, and Oppenheimer’s right hand for the last five years. The group refers to him as The Doug. The Doug thinks he looks like Steven Spielberg with long hair. The Doug likes to talk about Peak Oil and signal processing.

Postdocs Justin Crepp, Laurent Pueyo, Sasha Hinkley, and myself were also in the control room, a safe distance from the actual controls. Crepp wrote the software that achieves speckle reduction. It’s a work in progress known as the Justin Program. “At my Caltech reunion all my old classmates had hedge funds,” Vasisht said. “They have a lot more money then me. One of them asked me to invest so I put in a hundred.”

“A hundred what?” The Doug asked.

Pueyo was listening in. “Banking? Well, at least we’re not bored.”

The sky was sealed. Crepp fiddled with the Justin program. Hinkley read papers. Pueyo skyped with his Mom in France about his upcoming wedding in San Francisco. By the time the clouds cleared HR8799 was gone, so the telescope was trained on anther star, FU Ori in the constellation Orion.

Oppenheimer set the instrument to take fiveminute exposures before heading to the catwalk. With every iteration, a woman’s voice would mark data capture. “Image processing complete. Awaiting instructions.” The voice is sultry, receptive, and almost expectant. Oppenheimer had programmed her as a joke. She sounds like HAL’s humanizing mate. But unlike Arthur C. Clarke’s HAL, whose creepy conversation betrays progressive hints of malfunction, the woman’s words are unchanged even as Oppenheimer’s system faults in subtle ways, even as everyone’s head is buried in their hands. At one point earlier in the evening, sometime after the CAL’s hardware had warmed and before its software had failed, Oppenheimer lost his cool. He is intense, but rarely out of control. The night’s failures were too much. “There’s no tomorrow in optical astronomy,” he said. “The rotation of the Earth doesn’t care about your apologies.” He said it to no one in particular. He might as well have said it to himself. Project 1640 is a lose conglomeration of parts that barely fit, and people that fit together almost too well.

At 5am our brains were fried. I looked around and saw the same blank look in everyone’s eyes. Night lunches were strewn about. A Christmas tree was edging off its table. The smell of stale coffee rose from a dozen cups. The long night had removed key modules from our heads. As dawn lightened the sky and bodies felt the abuse of sleepless exhaustion, I could almost hear HAL in my head: “I’ve still got the greatest enthusiasm and confidence in the mission. And I want to help you. But my mind is going. I can feel it.”

***

The Drake equation looks like this: N = R* × fp × ne × fl × fi × fc × L

Where N is the number of civilizations in the galaxy with which we might communicate. N is directly proportional to R*, the average rate of star formation per year in our galaxy because, presumably, any habitable world will need a parent star. Then there are the whittling terms. What fraction of those stars have planets (fp)? How many of those planets are similar to earth (ne)? What fraction of these demonstrate signatures of life regardless of complexity (fl)? What fraction of the planets with life generate intelligent life, self aware and capable of formulating long, inscrutable equations (fi)? What fraction of planets with such beings communicate the signals of their technology in ways we can detect (fc)? And how long do these civilizations persist before they go extinct (L)? The Drake equation is like a confident man who stands tall before he is cut down to size. There are billions of stars in the galaxy, but successive fractionation can make astronomical numbers seem terrestrial. Frank Drake conceived the equation in 1960 after making the first attempts at detecting radio signals from extraterrestrial civilizations. Shortly thereafter, Drake organized a meeting on the detection of extraterrestrial intelligence, which ultimately seeded SETI. The equation was devised as talking points for an agenda. “I wrote down all the things you needed to know to predict how hard it’s going to be to detect extraterrestrial life.” Drake factorized each hurdle.

Some of the scientists on Project 1640 are shy about this notion of life on other planets. Others won’t shut up about it. If their willingness to speak on the subject were itself a spectrum, Oppenheimer would anchor the forthcoming believers. Mike Shao is far more reticent. When I asked him his thoughts on habitability, I pushed him on the potential momentousness of such a discovery. With a faint grin, he deflected my enthusiasm without being mean or unsupportive. “Yes, finding planets that can support life is a little bit different than finding a normal planet.” Really? A little bit different? Gauthum Vasisht is similarly evasive. “Frankly, I’m more interested in the architecture of planets. Fools like me get excited by any little thing. I guess some people are better at looking at the big picture.” Shao and Vasisht deployed the measured tones of science to diffuse the science fiction. The Doug, a self-anointed skeptic, was less willing to let a journalist run away with the idea of life on other worlds. “Astrobiology is a complete waste of time. The habitable zone is just a way to keep the public interested. There’s so much out there. We really don’t have a clue. I think it’s more bullshit than poetry.” Against the cynic, many of the students stood out in optimistic relief albeit tempered by their first few tastes of fiscal reality. At one point, while in the cage talking to Sasha Hinkley he got into a fit about our nation’s commitment to science. We were in the dark turning Allen wrenches a few millimeters one-way, and a few less back. “Americans spent $500 billion on gambling last year. Do you know how many more candidates we could generate with that kind of cash? It’s a real shame, man.”

Perhaps the most balanced of the astronomers I met was Charles Beichman, the Executive Director of the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute at Caltech. Chas, as he’s known to everyone on Project 1640, has been instrumental to the development of direct observation and isn’t shy about the work’s implications or its difficulties. “Astrobiology is part of the program. Biologists are part of our program. What do we mean by life? How much is specific to Earth, how much is based on universal principles? I’ll bet that life is abundant, but the thing is, I’ll probably never have to make good on that bet.” Beichman illustrated how far he was willing to go by hopping along the Drake equation. “We have an estimate for the number of stars in our galaxy, we know that each star has at least one planet, and we’re starting to get spectra that may nail down the fraction of these that are habitable.” But Beichman won’t touch the later terms. “The search for intelligent life is a search for electrical engineers.” If SETI is successful, we will know of at least one technological civilization capable of communication, but the discovery is not a quantity that can be factored back into the Drake. It’s one instance, one world with no statistical heft. It might be the most important discovery ever, but it would draw a line between two technological civilizations and dispense no clues as to whether the line is just one strand in a larger web.

Oppenheimer believes we have to look for life, simple or otherwise. In a review he wrote detailing the state of direct observation, Oppenheimer concluded with an impassioned mission statement, the kind you don’t see in the scientific literature. “Given the immensely compelling nature of the science involved in detecting places that might host life outside our Solar System, there is no question that, barring the annihilation of Homo sapiens, people will, and in some sense must, conduct such missions. We know how to do them now” (Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Volume 47, pages 253–289). The passage is both a goad and an admonition: Get on it! Why haven’t we done it yet? It’s a directive, a call to arms. I’m surprised he got away with it.

Oppenheimer’s personality is often in conflict with the inherent passivity of his craft. Astronomy is almost wholly observational. We are not in conversation with the cosmos, and it is this unidirectional flow of information that makes astronomy our purest and in some ways, most frustrating science. We cannot affect the product. The universe just sort of happens to us. You wait for light and it arrives with a message from the past, long after the source emitted it, perhaps long after the source has died. We have no capacity to affect the universe in any significant way. And because astronomy is so much a science of soaking things in, of waiting for information to come to you, we have built larger and larger telescopes to make sure nothing is missed of the light the universe bathes us in. The reward is deep astronomical vision.

But not yet deep enough. If we want to image other Earths, we need to do it from space. We can’t sift the light the way it needs to be sifted from the ground. The Terrestrial Planet Finder would have at least had a chance. “When you first think of a new idea, it’s like digging in topsoil, but with each technique you end up hitting bedrock,” said Beichman. The bedrock could be the limits of our technology or current understanding, it could be the realization of an engineering nightmare, or it could be political unwillingness. “So you get another shovel and dig somewhere else.” We live in a nation more attuned to our terrestrial messes than our larger place in the cosmos. We’re all about warming ice, warped economies, and war. To a dreamer with the long view on space and time, quotidian upkeep of our planet is both an afterthought and a black hole—so minor in the grand scheme but a sink for all of our collective energy.

***

Shortly before our trip to Palomar, Oppenheimer and I had lunch around the corner from the museum. While we were walking back, the sky opened over the Upper West Side and it began to pour. Stuck on Columbus Avenue, we ducked under an awning and stood around for a bit, waiting for the worst of it to pass. “Do you like rain?” Oppenheimer asked. We had been walking in silence for a few seconds, and I was asking all the questions, so I was a bit startled. I told him I didn’t mind as long as I wasn’t caught without my umbrella. His eyes lit up. “I prefer the rain,” he replied. “The sun can be so brilliant it blocks all the color.” I had never thought of color in this way. Everything seems so much more radiant in the sun. But to Oppenheimer the sun has a dulling effect. “I can see so much more clearly when it isn’t out.”

Whether it’s this planet or one 50 light years away, Oppenheimer quenches the glare of suns. Our exchange got me to thinking more about coronography. Project 1640 blocks starlight using a physical occulter and digital subtraction. But there are more fantastic, space-based notions as well. Mike Shao told me that when you build a one of a kind machine in space, “the cost is what the person writing the check is willing to pay.” So imagine a space-based telescope trained on a star whose planets are thought to be rocky and in close orbit, like our own. Now imagine that this telescope is equipped with its own shade, a giant piece of circular material two football fields in diameter that unfurls between the star and the telescope’s aperture. The edges of the shade gently oscillate around its center, the projection of a sunflower in interstellar space (Nature 2006 442(7098): 51–53). The star shade blocks a sun’s light before it enters the telescope. All that remains are the tiny specks around it, now in relief, amplified.

The dream is of amplitude. In both the astronomical and figurative sense, amplitude is what we want from these great eyes to the sky. We want to brighten the dim and we want to see with greater depth planets within the horizons of our perception. In one of our earliest conversations, Oppenheimer told me that when he sits down to think, all he has is the light. This insight is so clean and exhilarating. Light rains into a million backyard telescopes and a handful of engineering monuments. The universe transmits information in tight little beams. There’s nothing else. Large mirrors collect this information with great acuity. Large shades block the most obvious rays. But in the end all we want is the light from what we know must be there—hope is there—but can’t yet see. ![]()

The Wisdom of Psychopaths: What Saints, Spies, and Serial Killers Can Teach Us About Success

University of Oxford research psychologist Dr. Kevin Dutton reveals that there is a scale of “madness” along which we all sit. Incorporating the latest advances in brain scanning and neuroscience, Dutton demonstrates that the brilliant neurosurgeon who lacks empathy has more in common with a Ted Bundy who kills for pleasure than we may wish to admit, and that a mugger in a dimly lit parking lot may well, in fact, have the same nerveless poise as a titan of industry. Dutton argues that there are “functional psychopaths” among us—different from their murderous counterparts—who use their detached, unflinching, and charismatic personalities to succeed in mainstream society, and that shockingly, in some fields, the more “psychopathic” people are, the more likely they are to succeed. Dutton deconstructs this often misunderstood diagnosis through bold on-the-ground reporting and original scientific research as he mingles with the criminally insane in a high-security ward, shares a drink with one of the world’s most successful con artists, and undergoes transcranial magnetic stimulation to discover firsthand exactly how it feels to see through the eyes of a psychopath.

TAGS: Kevin Dutton, psychopathy, transcranial magnetic stimulation12-10-24

In this week’s eSkeptic:

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, Michael Shermer remembers Paul Kurtz, who died October 20, 2012 at the age of 86. Kurtz was one of the founders of the modern skeptical movement, and he embodied the principle of skepticism as thoughtful inquiry.

Paul Kurtz & the Virtue of Skepticism

How a Thoughtful, Inquiring, Watchman

Provided a Mark to Aim at

by Michael Shermer