12-07-11

In this week’s eSkeptic:

The Latest Episode of Mr. Deity: Mr. Deity and the Hitch

WATCH THIS EPISODE | DONATE | NEWSLETTER | FACEBOOK | MrDeity.com

About this week’s eSkeptic

Scientists are edging closer to providing logical and even potentially empirically testable hypotheses to account for the universe. In this week’s eSkeptic, Michael Shermer discusses 12 possible answers to the question of why there is something rather than nothing.

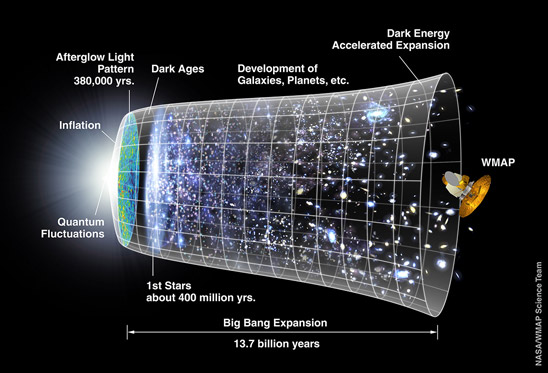

About the image below

Timeline of the Universe — A representation of the evolution of the universe over 13.7 billion years. The far left depicts the earliest moment we can now probe, when a period of “inflation” produced a burst of exponential growth in the universe. (Size is depicted by the vertical extent of the grid in this graphic.) For the next several billion years, the expansion of the universe gradually slowed down as the matter in the universe pulled on itself via gravity. More recently, the expansion has begun to speed up again as the repulsive effects of dark energy have come to dominate the expansion of the universe. The afterglow light seen by WMAP was emitted about 380,000 years after inflation and has traversed the universe largely unimpeded since then. The conditions of earlier times are imprinted on this light; it also forms a backlight for later developments of the universe. (Credit: NASA / WMAP Science Team)

Nothing is Negligible

Why There is Something Rather than Nothing

by Michael Shermer

Why is there something rather than nothing? The question is usually posed by Christian apologists as a rhetorical argument meant to pose as the drop-dead killer case for God that no scientist can possibly answer. Those days are over. Even though scientists are not in agreement on a final answer to the now non-rhetorical question, they are edging closer to providing logical and even potentially empirically testable hypotheses to account for the universe. Here are a dozen possible answers to the question

The Definitive Dozen

1 GOD. The theist’s answer to the question is that God existed before the universe and subsequently brought it into existence out of nothing (ex nihilo) in a single creation moment as described in Genesis. But the very conception of a creator existing before the universe and then creating it implies a time sequence. In both the Judeo-Christian tradition (along with the Babylonian pre-Judeo-Christian cosmogony) and the scientific worldview, time began when the universe came into existence, either through divine creation or the Big Bang. God, therefore, would have to exist outside of space and time, which means that as natural beings delimited by living in a finite universe, we cannot possibly know anything about such a supernatural entity. The theist’s answer is an untestable hypothesis and thus amounts to nothing more than a god-of-the-gaps argument.

2 WRONG QUESTION. Asking why there is something rather than nothing presumes “nothing” is the natural state of things out of which “something” needs an explanation. Maybe “something” is the natural state of things and “nothing” would be the mystery to be solved. As the physicist Victor Stenger notes in his book, The Fallacy of Fine Tuning: “Current cosmology suggests that no laws of physics were violated in bringing the universe into existence. The laws of physics themselves are shown to correspond to what one would expect if the universe appeared from nothing. There is something rather than nothing because something is more stable.”

3 GRAND UNIFIED THEORY. In order to answer the question, we need a comprehensive theory of physics that connects the subatomic world described by quantum mechanics to the cosmic world described by general relativity. As the Caltech cosmologist Sean Carroll notes in his book From Eternity to Here: “Possibly general relativity is not the correct theory of gravity, at least in the context of the extremely early universe. Most physicists suspect that a quantum theory of gravity, reconciling the framework of quantum mechanics with Einstein’s ideas about curved spacetime, will ultimately be required to make sense of what happens at the very earliest times. So if someone asks you what really happened at the moment of the purported Big Bang, the only honest answer would be: ‘I don’t know.’” That grand unified theory of everything will itself need an explanation, but it may be explicable by some other theory we have yet to comprehend out of our sheer ignorance at this moment in history.

4 BOOM-AND-BUST CYCLES. Sean Carroll also suggests that our universe may be just one in a series of boom-and-bust cycles of expansion and contractions of the universe, with our universe just one “episode” of the bubble’s eventual collapse and re-expansion in an eternal cycle, and therefore “there is no such thing as an initial state, because time is eternal. In this case, we are imagining that the Big Bang isn’t the beginning of the entire universe, although it’s obviously an important event in the history of our local region.”

5 DARWINIAN MULTIVERSE. According to the cosmologist Lee Smolin, in his book The Life of the Cosmos, our universe is just one of many bubble universes with varying sets of laws of nature. Those universes with laws of nature similar to ours will generate matter, which coalesces into stars, some of which collapse into black holes and a singularity, the same entity out of which our universe may have sprung. Thus, universes like ours give birth to baby universes with those same laws of nature, some of which develop intelligent life smart enough to discover this Darwinian process of cosmic evolution.

6 INFLATIONARY COSMOLOGY. In his 1997 book The Inflationary Universe, the cosmologist Alan Guth proposes that our universe sprang into existence from a bubble nucleation of spacetime. If this process of universe creation is natural, then there may be multiple bubble nucleations that give rise to many universes that expand but remain separate from one another without any causal contact between them.

7 MANY-WORLDS MULTIVERSE. According to the “many worlds” interpretation of quantum mechanics, there are an infinite number of universes in which every possible outcome of every possible choice that has ever been available, or will be available, has happened in one of those universes. This many-worlds multiverse is grounded in the bizarre findings of the famous “double-slit” experiment, in which light is passed through two slits and forms an interference pattern of waves on a back surface (like throwing two stones in a pond and watching the concentric wave patterns interact, with crests and troughs adding and subtracting from one another). The spooky part comes when you send single photons of light one at a time through the two slits—they still form an interference wave pattern even though they are not interacting with other photons. How can this be? One answer is that the photons are interacting with photons in other universes! In this type of multiverse you could meet your doppelgänger, and depending on which universe you entered, your parallel self would be fairly similar or dissimilar to you, a theme that has become a staple of science fiction (see, for example, Michael Crichton’s Timeline).

8 BRANE UNIVERSES. A multi-dimensional universe may come about when three-dimensional “branes” (a membrane-like structure on which our universe exists) moves through higher-dimensional space and collides with another brane, the result of which is the energized creation of another universe.

9 STRING UNIVERSES. A related multiverse is derived through string theory, which by at least one calculation allows for 10500 possible worlds, all with different self-consistent laws and constants. That’s a 1 followed by 500 zeroes possible universes (12 zeroes is a trillion!). In his book The Unconscious Quantum, Victor Stenger published the results of a computer model that analyzes what just 100 different universes would be like under constants different from our own, ranging from five orders of magnitude above to five orders of magnitude below their values in our universe. Stenger found that long-lived stars of at least 1 billion years—necessary for the production of life-giving heavy elements—would emerge within a wide range of parameters in at least half of the universes in his model.

10 QUANTUM FOAM MULTIVERSE. In this model, universes are created out of nothing, but in the scientific version of ex nihilo the nothing of the vacuum of space actually contains the theoretical spacetime mishmash called quantum foam, which may fluctuate to create baby universes. In this configuration, any quantum object in any quantum state may generate a new universe, each one of which represents every possible state of every possible object. This is Stephen Hawking’s explanation for the fine-tuning problem that he himself famously presented in his 1996 book (co-authored with Roger Penrose) The Nature of Space and Time: “Quantum fluctuations lead to the spontaneous creation of tiny universes, out of nothing. Most of the universes collapse to nothing, but a few that reach a critical size, will expand in an inflationary manner, and will form galaxies and stars, and maybe beings like us.”

11 M-THEORY GRAND DESIGN. Stephen Hawking has continued working on this question, and this month, he and the Caltech mathematician Leonard Mlodinow present their answer in a book entitled The Grand Design. They approach the problem from what they call “model-dependent realism,” based on the assumption that our brains form models of the world from sensory input, that we use the model most successful at explaining events, and that when more than one model makes accurate predictions “we are free to use whichever model is most convenient.” Employing this method, they write, “it is pointless to ask whether a model is real, only whether it agrees with observation.” The dual wave/particle models of light are an example of model-dependent realism, where each one agrees with certain observations but neither one is sufficient to explain all observations. To model the entire universe, Hawking and Mlodinow employ “M-Theory,” an extension of string theory that includes 11 dimensions and incorporates all five current string theory models. “M-theory is the most general supersymmetric theory of gravity,” Hawking and Mlodinow explain. “For these reasons M-theory is the only candidate for a complete theory of the universe. If it is finite—and this has yet to be proved—it will be a model of a universe that creates itself.” Although they admit that the theory has yet to be confirmed by observation, if it is, then no creator explanation is necessary because the universe creates itself. I call this auto-ex-nihilo.

12 NOTHING IS UNSTABLE, SOMETHING IS NATURAL In his 2012 book, A Universe From Nothing, the cosmologist Lawrence M. Krauss attempts to link quantum physics to Einstein’s gravitational theory of general relativity to explain the origin of something (including a universe) from nothing: “In quantum gravity, universes can, and indeed always will, spontaneously appear from nothing. Such universes need not be empty, but can have matter and [electromagnetic] radiation in them, as long as the total energy, including the negative energy associated with gravity [balancing the positive energy of matter], is zero.” And: “In order for the closed universes that might be created through such mechanisms to last for longer than infinitesimal times, something like inflation is necessary.” Observations have revealed that, in fact, the universe is flat (there is just enough matter to eventually halt its expansion), its energy is zero, and it underwent rapid inflation, or expansion, shortly after the Big Bang as described by inflationary cosmology. Thus, Krauss concludes, “quantum gravity not only appears to allow universes to be created from nothing—meaning…the absence of space and time—it may require them. ‘Nothing’—in this case no space, no time, no anything!—is unstable.”

Putting Something to the Test

Many of these dozen explanations are testable. The theory that new universes can emerge from collapsing black holes may be illuminated through additional knowledge about the properties of black holes. Other bubble universes might be detected in the subtle temperature variations of the cosmic microwave background radiation left over from the Big Bang of our own universe. NASA recently launched a spacecraft constructed to study this radiation. Another way to test these theories might be through the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) that is designed to detect exceptionally faint gravitational waves. If there are other universes, perhaps ripples in gravitational waves will signal their presence. Maybe gravity is such a relatively weak force (compared to electromagnetism and the nuclear forces) because some of it “leaks” out to other universes. Maybe.

After a column I wrote in Scientific American on this topic (“Much Ado About Nothing,” May, 2012), I received an email from the Columbia University theoretical physicist Peter Woit cautioning me not to put too much emphasis on any one of these hypotheses/answers to the question of why there is something rather than nothing, noting that even these proposed tests probably themselves lack validity, if they could ever be conducted in reality. He explained that his skepticism came not out of religious conviction: “I’m as much of an atheist as anyone, and I’m really disturbed to see arguments being made that are going to end up discrediting skepticism and atheism.” He then posted a blog commentary on my Scientific American column, noting that my “authority here is the Hawking/Mlodinow popular book, but he’s also convinced that WMAP and LIGO are somehow going to provide evidence for multiverses, something that even the most far-out theorists in this field aren’t claiming.” Regarding my comment that perhaps gravity “leaks” out to other universes Woit responds: “Nobody seems to have told Shermer that this is not an idea taken seriously by a significant number of theorists, or that LHC data has shot down the hopes of the one or two such theorists.” Woit was prescient in that the prominent Intelligent Design creationist William Dembski did highlight Woit’s skepticism at his blog Uncommon Descent (“Serving the Intelligent Design Community”), quoting Woit and commenting: “Don’t nobody tell Shermer. It’s more fun this way.”

Given the fact that I appreciated Peter Woit’s skeptical book on string theory (Not Even Wrong: The Failure of String Theory and the Search for Unity in Physical Law), I queried my sources. Physicist Victor Stenger responded: “The multiverse is not nonsense. It is based on good theory, but only theory. It is, in principle, detectable by measuring an anisotropy in the cosmic background radiation. That’s why I did not rely on it in The Fallacy of Fine-Tuning. I agree with Woit on M-theory, though.” Caltech physicist Leonard Mlodinow said he doubts that either he or Woit knows what “most physicists” think about the multiverse, and then opined that “most cosmologists certainly believe it,” recalling that Brian Greene “outlined the general thinking (as opposed to, say, Hawking’s particular views) very well in his book on it” (The Hidden Reality). Finally, Caltech physicist and cosmologist Sean Carroll noted: “You are completely correct, the multiverse is an idea that pops out of inflation (and string theory), not one that is put in out of desperation. Here is a column of my own making exactly this point. Carroll then cautioned: “Obviously the entire set of ideas is controversial and speculative, and should be presented as such, but it’s taken very seriously by a large number of extremely smart and respectable people.” For example: Leonard Susskind, Alex Vilenkin and Alan Guth (on the pro-multiverse side) and David Gross, Paul Steinhardt, and Edward Farhi (skeptical of the multiverse side).

God, Science, and the Great Unknown

In the meantime, while scientists sort out the science to answer the question Why is there something instead of nothing?, in addition to reviewing these dozen answers it is also okay to say “I don’t know” and keep searching. There is no need to turn to supernatural answers just to fulfill an emotional need for explanation. Like nature, the mind abhors a vacuum, but sometimes it is better to admit ignorance than feign certainty about which one knows not. If there is one lesson that the history of science has taught us it is that it is arrogant to think that we now know enough to know that we cannot know. Science is young. Let us have the courage to admit our ignorance and to keep searching for answers to these deepest questions.

Skeptical perspectives on the universe…

-

The Grand Design

The Grand Design

by Leonard Mlodinow -

When and how did the universe begin? Why are we here? Why is there something rather than nothing? What is the nature of reality? Why are the laws of nature so finely tuned as to allow for the existence of beings like ourselves? And, finally, is the apparent “grand design” of our universe evidence of a benevolent creator who set things in motion—or does science offer another explanation? In this lecture by Leonard Mlodinow, based on his co-authored book with Stephen Hawking, answers to these ultimate questions are answers based on the most recent scientific evidence.

-

How Old is the Universe? and

How Old is the Universe? and

The Shape of Inner Space

(two lectures on one DVD)

by Dr. David Weintraub and Dr. Shing-Tung Yau -

It’s all very well for astronomers to say that the universe is 13.7 billion years old, but how do they know? Weintraub explains various dating approaches and illustrates the work of astronomers to find the answer to one of the most basic questions about our universe.

Dr. Yau tells the story of the six-dimensional geometric spaces that may be more than a trillion times smaller than an electron (and also one of the defining features of our universe), which physicists have dubbed “Calabi-Yau manifolds.” Dr. Yau managed to prove the existence, mathematically, of these spaces, despite the fact that he had originally set out to prove that such spaces could not possibly exist.

-

Cosmos (7-DVD set)

Cosmos (7-DVD set)

by Carl Sagan -

The Collector’s edition boxed set of 7 DVDs of the 13 hour series narrated in 1980 by Carl Sagan and revamped in 2000 with up-to-date science and images. The definitive tour of our universe. Inspiring!

12-07-04

In this week’s eSkeptic:

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

How to Learn to Think Like a Scientist (Without Being a Geek)

In this week’s Skepticblog, Michael Shermer shares his experience of what it was like teaching a course in Skepticism 101.

NEW ON MICHAELSHERMER.COM

Aunt Millie’s Mind

In Michael Shermer’s July “Skeptic” column for Scientific American, he reminds us that the hypothesis that the brain creates consciousness has vastly more evidence for it than the hypothesis that consciousness creates the brain.

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 186

Interviews with Todd Stiefel and Mark Edward

In this episode of Skepticality, Derek sits down with Todd Stiefel to talk about his involvement in recent, and upcoming secular public events and campaigns. His latest is working to collect one million dollars (or more) for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society through the Foundation Beyond Belief. Also in this episode, Derek catches up with Mark Edward, a well known mentalist, about his new book, Psychic Blues, and the experiences which led him to write the book and his thoughts on the varied types of current psychics who are operating out there today, and through the recent past.

About this week’s eSkeptic

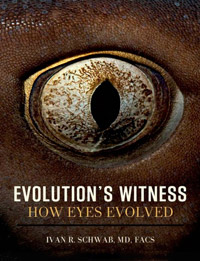

In this week’s eSkeptic, Donald R. Prothero reviews Ivan R. Schwab book, Evolution’s Witness: How Eyes Evolved (Oxford University Press, New York, 2012, ISBN 978-0-19-536974-8). Read Prothero’s bio after the article.

How the Blind Watchmaker

Made Eyes

by Donald R. Prothero

Since the days of Darwin, eyes and evolution have been an irresistible topic for scientists and amateur authors alike. British biologist St. George Jackson Mivart was initially a supporter of Darwin, but when his Catholic religion caused conflict with Thomas Henry Huxley in 1871, he changed to a critic. Mivart’s critique focused on the issue of the perfection of the human eye and how he could not fathom how it could have evolved by natural selection and random chance (a point still raised by creationists today who know nothing about comparative biology).

In later editions of On the Origin of Species, Darwin specifically addressed Mivart’s criticism and carefully explained how the incipient stages of complex structures like the eye could be useful, and could have evolved by small steps; it did not require a giant leap to the complexity to develop the human eye. As Darwin first showed, nature is full of examples of every kind of photoreceptor, from simple light-sensitive cells to eyespots to simple eyes with no lenses, to a variety of solutions of seeing with more and more complex eyes. Once you arrange these solutions in an array, it is only a small step from one to the next, more complex eye. (Indeed, many animals actually show this transition during their embryonic development as their eyes change, and in some organisms, the eyes develop differently in males and females). In fact, the passages where Darwin talks about the eye are one of the most frequently “quote mined” by creationists trying to distort Darwin’s meaning, because they quote only the beginning of the paragraph where Darwin is setting up the creationist position in order to shoot it down the in the rest of the passage (which creationists never quote). Here is the first section that creationists quote (On the Origin of Species, 6th ed., 1872, 143–144):

To suppose that the eye, with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest possible degree.

Here is the rest of the quote that creationists conveniently leave out:

Yet reason tells me, that if numerous gradations from a perfect and complex eye to one very imperfect and simple, each grade being useful to its possessor, can be shown to exist; if further, the eye does vary ever so slightly, and the variations be inherited, which is certainly the case; and if any variation or modification in the organ be ever useful to an animal under changing conditions of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could be formed by natural selection, though insuperable by our imagination, can hardly be considered real. How a nerve comes to be sensitive to light, hardly concerns us more than how life itself first originated; but I may remark that several facts make me suspect that any sensitive nerve may be rendered sensitive to light, and likewise to those coarser vibrations of the air which produce sound.

The rest of Darwin’s chapter goes into great depth describing the full range of photoreceptor solutions in the animal kingdom, which creationists also conveniently fail to address.

Fast-forward 153 years later to the culmination of this line of argument, represented by Ivan Schwab’s outstanding book Evolution’s Witness: How Eyes Evolved. There have been a number of scientific papers that have expanded on Darwin’s comparative sequence of ocular solutions, but none in the beautiful full-color coffee-table book format that extensively reviews photoreception across all of biology, as does Schwab’s book. Schwab is a professor of ophthalmology at University of California Davis, so he knows eyes in a way that few biologists do, but he also takes great trouble to study and image photoreceptors from nearly every group of living organisms. The book shows not only spectacular color photographs of a wide range of organisms and close-ups of their eyes, but many images of histological sections through the eyes and head (done by Richard Dubielzig, DVM), color reconstructions of prehistoric animals by renowned paleoartist John Sibbick, and microphotography of eye histology. Detailed discussions of the eye anatomy of many key living organisms are provided, along with speculation about the eye anatomy of fossils with excellent preservation. Some, like trilobites, have preserved their crystal calcite lenses unaltered, so we can actually see what they could see. The anatomical discussion might be heavy going for those without any background in biology, but the author provides excellent diagrams and definitions of every anatomical term, plus a glossary, so those who wish to dig in and learn the material will be rewarded.

The book also attempts not just a comparative biology exercise, but a fully chronological account of the geological factors that were in play when each type of eye arose prehistorically. Thus, rather than running through the full gamut of eye types in, say, phylum Arthropoda or phylum Chordata, the chapters jump from the kinds of eyes that existed in invertebrates of a given geological period to the contemporary vertebrates, and back again. This exposition may be a little hard to follow for some readers, but it does allow one to see when each type of eye arose and under what geological conditions. Thus, we can better understand, for example, how 300 m.y. old Carboniferous dragonflies with wingspans almost 3 feet across had eyes the size of golf balls! They, like the 9-foot Arthropleura (a sowbug relative on steroids) or the foot-long cockroaches of this period, were able to grow so large because atmospheric oxygen levels at that time were much higher; oxygen is a critical limiting factor not only for arthropod growth, but especially for eye development. Elsewhere, he describes the amazing dolphin-like marine reptiles known as ichthyosaurs, some of which had eyes the size of beach balls, the largest eyes ever known. These animals apparently were divers into the dark depths of the oceans where they must have hunted prey (possibly large squid like modern sperm whales hunt) that live at such depths.

Schwab begins at the beginning of the simplest life forms, discussing the chemicals and pigments found even in bacteria and algae, and how many (besides chlorophyll) are sensitive to light. He shows how some non-photosynthetic light-sensitive pigments have non-light-sensitive precursors, and evolved before the advent of photoreceptors, then were later co-opted for light sensitivity. Schwab goes into the recent research on evolutionary development of eyes, and how certain genes turn on or off expression of certain eye features, or even the entire eye. He reminds us how many animals have no need for sensitivity to light at all, let alone photoreceptors or eyes, and dispels our anthropomorphic notion that eyes are essential to evolutionary success.

In discussing the appearance of the first real eyes of the trilobites in the Cambrian, Schwab does not make the mistake that Andrew Parker made in his 2004 book In the Blink of an Eye: How Vision Caused the Big Bang of Evolution. Parker’s book was excoriated in the scientific community, not only for its execrable writing style and lack of proper references, but for the even simpler reason that the “Cambrian explosion” was no “explosion” (it took at least 20–80 million years in a series of steps) and that the trilobites and their eyes were one of the last events in this long slow process, so they are unlikely to have caused anything more than the late radiation of more trilobites.

Finally, in his review of cephalopod eyes, Schwab shows how the structure of the fluid-filled eyeball of an octopus evolved independently in that lineage and in the vertebrates—but the octopus eye is actually designed better than our eye! It has no “blind spot” in the retina caused by the exit of the optic nerve, and its layers of photoreceptors are not buried under several other layers of cells, distorting the vision, as our retinas are. The next time you run into a creationist who rhapsodizes about how beautifully designed nature is, remind them of the flawed construction of our eyes compared to that of an octopus or squid, and ask what that tells them about the Designer!

In a project this large in scope, small errors are bound to creep in, especially in areas far from the author’s expertise in eye anatomy. For example, he mentions the discredited notion that a meteorite impact might have something to do with the great Permian extinction; he follows the controversial idea that turtles are nested within Diapsida; but he retains the outdated notions that mesonychids are closer relatives of whales than hippos and other artiodactyls. These can be forgiven, because the author is making an attempt to reach across disciplines and paint a broad picture in a geological context, and such an effort is hard for anyone, regardless of specialty, to manage.

In the broader sense, the entire book is an outstanding antidote to scientific ignorance and creationist lies. It is beautifully written and illustrated, yet the writing is accessible to anyone with some biology background and a willingness to follow the details carefully. The evidence for evolution screams out at you page after page. Like Darwin did in 1859, Schwab pounds the case home with example after example in a way that no creationist can rebut. Among the overwhelmingly positive reviews the book has received in the professional journals and on the Internet, there are three pathetic one-sentence negative reviews by creationist trolls on the book’s Amazon.com page, which clearly show that they didn’t actually read the book and could not comprehend it. Indeed, one of them admits that he gave a bad review to the book after only reading the “look inside” feature on the Amazon.com site and skimming the few pages that are presented. If that doesn’t summarize creationist “scholarship” in a nutshell, nothing does! ![]()

About the Author of this Review

DR. DONALD R. PROTHERO was Professor of Geology at Occidental College in Los Angeles, and Lecturer in Geobiology at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. He earned M.A., M.Phil., and Ph.D. degrees in geological sciences from Columbia University in 1982, and a B.A. in geology and biology (highest honors, Phi Beta Kappa) from the University of California, Riverside. He is currently the author, co-author, editor, or co-editor of 32 books and over 250 scientific papers, including five leading geology textbooks and five trade books as well as edited symposium volumes and other technical works. He is on the editorial board of Skeptic magazine, and in the past has served as an associate or technical editor for Geology, Paleobiology and Journal of Paleontology. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America, the Paleontological Society, and the Linnaean Society of London, and has also received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Science Foundation. He has served as the President and Vice President of the Pacific Section of SEPM (Society of Sedimentary Geology), and five years as the Program Chair for the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. In 1991, he received the Schuchert Award of the Paleontological Society for the outstanding paleontologist under the age of 40. He has also been featured on several television documentaries, including episodes of Paleoworld (BBC), Prehistoric Monsters Revealed (History Channel), Entelodon and Hyaenodon (National Geographic Channel) and Walking with Prehistoric Beasts (BBC). His website is: www.donaldprothero.com. Check out Donald Prothero’s page at Shop Skeptic.

Skeptical perspectives on evolution and Darwin…

-

Evolution: How We and All Living Things Came to Be

Evolution: How We and All Living Things Came to Be

Written by Daniel Loxton; illustrated by Daniel Loxton

with Jim W.W. Smith -

Can something as complex and wondrous as the natural world be explained by a simple theory? The answer is YES, and now Evolution explains how in a way that makes it easy to understand. Based on acclaimed articles from Junior Skeptic (Skeptic magazine’s science insert for kids) Evolution is a gorgeous hardcover with dust jacket, packed throughout with dazzling full-color art. This spectacularly illustrated introduction to the theory of evolution takes us from Charles Darwin to modern-day science. Along the way, Evolution answers common questions (and clears up misunderstandings) that sometimes confuse people about the history of life on Earth.

-

Why Darwin Matters: The Case Against Intelligent Design

Why Darwin Matters: The Case Against Intelligent Design

by Michael Shermer -

Evolution happened, and the theory describing it is one of the most well founded in all of science. Then why do half of all Americans reject it? Michael Shermer defuses the hesitation people have of accepting the theory of evolution by examining what evolution really is, how we know it happened, and how to test it. Dr. Shermer was once an evangelical Christian and a creationist, and is now one of the best-known public intellectuals defending evolutionary theory, so Why Darwin Matters provides readers with an insiders’ guide to the evolution-creation debate, in which he shows why creationism and Intelligent Design are not only bad science, they are bad theology, and why science should be embraced by people of all beliefs.

-

The Blind Watchmaker: Why the Evidence of Evolution Reveals a Universe Without Design

The Blind Watchmaker: Why the Evidence of Evolution Reveals a Universe Without Design

by Richard Dawkins -

One of the most famous creationist arguments originated with 18th century theologian William Paley who suggested that since a watch should have a maker, the natural world also needed to have one. Just as a watch is too complicated and too functional to have sprung into existence by accident, so too must all living things, with their far greater complexity, be purposefully designed. It was Charles Darwin’s brilliant discovery that put the lie to these arguments. But only Richard Dawkins could have written this eloquent riposte to the creationists…

-

Evolution: How We Know it Happened

Evolution: How We Know it Happened

& Why it Matters

by Dr. Donald R. Prothero -

The hottest cultural controversy of 2005 was the Intelligent Design challenge to the theory of evolution, being played out in classrooms and courtrooms across America. The crux of the argument made by proponents of Intelligent Design is that the theory of evolution is in serious trouble. They claim that the evidence for evolution is weak, the gaps in the theory are huge, and that these flaws should be taught to students. In this brilliant synthesis of scientific data and theory, Occidental College geologist, paleontologist, and evolutionary theorist Dr. Donald Prothero will present the best evidence we have that evolution happened, why Darwin’s theory still matters, and what the real controversies are in evolutionary biology.

Announcing The Amaz!ng Meeting 2012

Southpoint Hotel & Casino, Las Vegas, NV

July 12–15, 2012

THE AMAZ!NG MEETING (TAM) is an annual celebration of science, skepticism and critical thinking. People from all over the world come to TAM each year to share learning, laughs and the skeptical perspective with their fellow skeptics and a host of distinguished guest speakers and panelists.

The James Randi Educational Foundation (JREF) has hosted its annual Amaz!ng Meeting since 2003 as a way to promote science, skepticism and critical thinking about paranormal and supernatural claims to the broader public. TAM has been held in Las Vegas, NV since 2004 and has become the world’s largest gathering of like-minded science-advocates and skeptics.

With yet another incredible lineup of speakers, hands-on workshops, and entertainment, this is sure to be an Amaz!ng Meeting you won’t want to miss! Check out the entire program, and follow @jref on Twitter for the latest #TAM2012 news and announcements.

12-06-27

Michael Shermer Announces Skepticism 101

I am exceptionally proud to announce today the beta launching of Skepticism 101: The Skeptical Studies Curriculum Resource Center, where we provide skeptical resources, freely available to anyone, anywhere, anytime. Brought to you by the Skeptics Society and under the direction of Anondah Saide and William Bull, Skepticism 101 is a resource center for educators, teachers, administrators, students, and skeptics in all fields and walks of life to provide you with the resources you need to teach people how to think skeptically and critically about any and all claims.

We Are All Teachers. We Are All Educators.

Every time you talk to someone anywhere about anything you have an opportunity to teach skepticism and critical thinking, both of which are at the core of science. We want to change the world. Ideas and how to think about them is at the foundation of all change, especially beliefs. To that end we have launched Skepticism 101 and invite you to get involved by contributing any materials that you think might be relevant, interesting, and important to our cause of making the world a better place through reason and science. We are looking for suggested readings, course syllabi, PowerPoint presentations, student projects, papers, and videos that you have written and/or produced, and anything else you can think of that might be relevant. You can browse resources by topic (e.g. psychics), resource type (e.g. course syllabi), academic discipline (e.g. biology), or academic level (e.g. college).

Thank you to everyone who has contributed thus far—in both educational materials and financial support—and I invite you all to make a contribution in any way you can. Think of this as the launching of a Skeptical Library of Alexandria! To participate contact the Skepticism 101 Resource Center Director Anondah Saide: skepticism101@skeptic.com

In addition to those who contributed teaching materials we are especially grateful to our significant supporters in last year’s fundraising campaign on behalf of Skepticism 101: Bill Nye, Steven Ridley, Robert Engman, Richard Epstein, Jones Hamilton, James Alexander, Jean Bettanny, Arnold Lau, David Kaloyanides, Jeff Kodosky, Marvin Mueller, and Michael Roberts. Special thanks go to Tyson Jacobsen, who also attended Michael Shermer’s first official course in skepticism last fall, “Skepticism 101: How to Think Like a Scientist Without Being a Geek.”

12-06-20

In this week’s eSkeptic:

OUR NEW LARGE SIZE BUMPER STICKER (shown above) is designed to withstand the elements, our new self-adhesive bumper stickers (made from the highest quality weather resistant and laminated vinyl) are ideal for use on vehicle bumpers, windows, refrigerators, school lockers and binders, or just about anywhere…

Wear Your Skepticism Proudly!

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

The Reality Distortion Field

In this week’s Skepticblog, Michael Shermer discusses Steve Job’s “Reality Distortion Field,” reminding us that Jobs’ modus operandi of ignoring reality is a double-edge sword, and that reality must take precedence over willful optimism.

Mike McRae

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 185

Interview with Mike McRae

In this episode of Skepticality, Derek sits down with Mike McRae, a science writer and touring science communicator for Questacon: Australia’s National Science and Technology Center. Mike has recently released his latest book, Tribal Science. Derek and Mike discuss how the book came about and how our current culture still owes many of its common illogical behaviors to our tribal nature.

About this week’s eSkeptic

Who needs make-believe, when nature offers so much excitement and so many mysteries waiting to be solved? In this week’s eSkeptic, Peter Boghossian reviews Guy P. Harrison’s latest book, 50 Popular Beliefs That People Think are True (Prometheus Books, 2012, ISBN-13: 978-1616144951). Dr. Peter Boghossian teaches critical thinking, science and pseudoscience, and atheism at Portland State University.

Bogus, Bunk, and B.S.

by Peter Boghossian

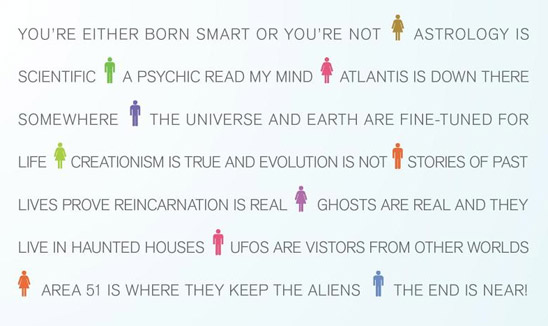

Rarely has a skeptic gone to battle against nonsense with the warmth and humor found in 50 Popular Beliefs That People Think are True. Author Guy P. Harrison, an award-winning journalist and long-time advocate for science and reason, delivers a grand tour though the bizarre ecosystem of irrational beliefs and extraordinary claims. Harrison deftly and compellingly demonstrates how science and reality are preferable to superstition and delusion. Who needs make-believe, he asks, when nature offers so much excitement and so many mysteries waiting to be solved?

Readers will find first-rate skeptical treatments of UFOs, psychics, ESP, Atlantis, Bigfoot, astrology, Nostradamus, the Moon landing hoax, Area 51, and other usual suspects—but they will also discover topics that are not as well considered by the skeptical community, but should be. For example, skeptical perspectives on biological race categories, and the race-sports dynamic—covered in the pages of Skeptic magazine in the 1990s but not discussed recently—are thoughtful additions to the skeptical canon. Moreover, his arguments about how television news distorts our view of the real world, even for smart people who should know better, is yet another topic that further differentiates this book from the available literature. Add to this his analysis of how global warming is assessed as a political issue rather than a matter of science, and readers have a comprehensive, provocative tome that will captivate as it educates.

Still another differentiating characteristic of 50 Popular Beliefs That People Think are True, is that it has the potential to make a lasting impression on those who harbor beliefs that are out of alignment with reality. Harrison genuinely attempts, and succeeds, at being gentle and sympathetic toward people who hold unwarranted beliefs—even as he mercilessly and systematically annihilates justifications for the beliefs under examination. He articulates how we are all vulnerable to falling for bad ideas and misinterpreting reality due to the influence of culture and the way our brains routinely deceive us about reality. For example, Harrison explains how vision and memory can be misleading. He writes that human memory is not the biological version of a DVR playback system that most people imagine; memory is more like having a little old man who lives inside your head. When you want to remember something, you have to tap him on the shoulder and then listen to the creative tale he weaves about your past. And like most storytellers, the old man adds a bit here, subtracts a bit there, embellishes, distorts, and even lies in an attempt to deliver to you the best story possible. For an individual, however, memories can feel like a perfectly reliable replay of what happened, no matter how inaccurate they happen to be. All of this has obvious implications for UFO encounters, ghost sightings, psychic readings, and so on. But beyond this, Harrison helps people feel as if it was not their fault that they were unduly influenced and that this influence skewed the mechanism of belief formation; now that they are aware of influences that take them away from reality they can realign their beliefs on the basis of reliable evidence, and do so without shame, guilt or recrimination.

Harrison’s gentle touch doesn’t mean he won’t play rough when it’s needed. Chapters on alternative medicine and the anti-vaccine movement include scathing condemnations of those who promote medical quackery over evidence-based healthcare at the expense of human lives. Through detailed examples, he explains the gravity of what’s at stake because of the tragedy of unreason. For example, Harrison reveals his understandable frustration and anger regarding the strange phenomenon of torturing and killing “witches” in the 21st century. From the abuse of “child witches” by Christians in Africa to the murder of “sorcerers” in rural India by people who fear magic, he shows that humankind has not completely exited the Dark Ages. However, rather than simply state the obvious—that killing people for being witches is tragically ignorant and morally repugnant—Harrison goes further to clearly explain how faith-based thinking in all forms is non-thinking and therefore risky. He shows how even believing in something that seems benign on the surface, such as Bigfoot or the Bermuda Triangle, is a symptom of sloppy thinking that could lead one directly into the grip of a belief that’s pernicious or even fatal.

Fortunately, Harrison does not sidestep religion. He pulls no punches in thorough skeptical assaults on prayer, prophecies, miracles, faith healing, angels, heaven, and gods. He avoids condescension toward believers, but provides the necessary brutal frankness regarding the weakness of their claims. Like any well-versed skeptic, Harrison does not claim to disprove or to know that many of these misaligned beliefs are definitively false. Rather, he shows that a multiplicity of claims people believe as true do not have sufficient evidence to warrant belief. (His personal observations at a Benny Hinn faith healing spectacle are informative and highly entertaining. He also shares his own experience of being prayed for after a cycling accident and his encounter with a “spirit guide” during a vision quest).

This is a book that both believers and skeptics should read. Many believers are likely to enjoy having their beliefs challenged in this often gentle and always thoughtful way. Seasoned skeptics will find plenty of fresh information and new ways to approach conversations with believers. Readers will also appreciate his vigorous defense of the skeptical worldview, in particular how it protects one from harm and frees one up from empty distractions in order to live life more fully. Finally, numerous interviews with prominent scientists and notable people add to the book’s comprehensiveness. Each chapter ends with a useful list of recommended books, documentaries, and Web sites related to the particular topic of that chapter. 50 Popular Beliefs That People Think are True also includes humorous cartoon illustrations, as well as some photographs and statistical illustrations. It is an ideal text for an introductory Science and Pseudoscience or Critical Thinking course. It is clear, comprehensive, non-threatening yet thought provoking while remaining accessible. It’s also a much welcomed and needed addition to every skeptic’s reading list. ![]()

Skeptical perspectives on pseudoscience

and belief in weird things…

-

The Believing Brain

The Believing Brain

by Michael Shermer -

In this, his magnum opus synthesizing 30 years of research, Dr. Michael Shermer presents his comprehensive theory on how beliefs are born, formed, nourished, reinforced, challenged, changed, and extinguished. Essentially: beliefs come first, explanations for beliefs follow. We form our beliefs for a variety of subjective, personal, emotional, and psychological reasons in the context of environments created by family, friends, colleagues, culture, and society at large; after forming our beliefs we then defend, justify, and rationalize them with a host of intellectual reasons, cogent arguments, and rational explanations.

-

Why People Believe Weird Things

Why People Believe Weird Things

by Michael Shermer -

A no-holds-barred assault on popular superstitions and prejudices, this book debunks these nonsensical claims and explores the very human reasons people find otherworldly phenomena, conspiracy theories, and cults so appealing.

GET AN AUTOGRAPHED COPY OF THIS BOOK.

-

The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience

The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience

Michael Shermer, Pat Linse, Eds. -

Two volumes include and A–Z debunking of all things paranormal and pseudoscientific including case studies and in-depth analyses, a pro and con debate section, plus historical documents on many topics. This was published as a library reference book. Save over $50.00 off the price charged to libraries. GET THE SKEPTIC ENCYCLOPEDIA.

Announcing The Amaz!ng Meeting 2012

Southpoint Hotel & Casino, Las Vegas, NV

July 12–15, 2012

THE AMAZ!NG MEETING (TAM) is an annual celebration of science, skepticism and critical thinking. People from all over the world come to TAM each year to share learning, laughs and the skeptical perspective with their fellow skeptics and a host of distinguished guest speakers and panelists.

The James Randi Educational Foundation (JREF) has hosted its annual Amaz!ng Meeting since 2003 as a way to promote science, skepticism and critical thinking about paranormal and supernatural claims to the broader public. TAM has been held in Las Vegas, NV since 2004 and has become the world’s largest gathering of like-minded science-advocates and skeptics.

With yet another incredible lineup of speakers, hands-on workshops, and entertainment, this is sure to be an Amaz!ng Meeting you won’t want to miss! Check out the entire program, and follow @jref on Twitter for the latest #TAM2012 news and announcements.

12-06-13

In this week’s eSkeptic:

Skeptics are Redoubtable

The hosts of MonsterTalk interview Sharon Hill, creator of the website Doubtful News. The discussion includes updates on the latest in monster news trends, as well as information about The Amaz!ng Meeting—the James Randi Educational Foundation’s annual meeting of skeptical scientists, researchers, artists, performers, teachers and other rational-minded folk in Las Vegas, Nevada. Also in this episode, Brian Thompson of the JREF stops by to discuss TAM 2012.

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, Rachel Pridgen reviews two books: Nonbeliever Nation: The Rise of Secular Americans by David Niose (Palgrave/Macmillan, 2012, ISBN 13: 978-0-230-33895-1) and Religion for Atheists: A Non-believer’s Guide to the Uses of Religion by Alain de Botton (Pantheon, 2012, ISBN 13: 978-0-307-37910-8).

Rachel Pridgen is credited with preserving the sanity of countless women by hosting group therapy in the form of workout sessions, knit nights, and tea/wine parties. She is a freelance writer with a popular blog depicting her experiences as a freethinking mother in southern Alabama. Her areas of interest and research include religious psychology and early education; the history of philosophy and science; and the intersection between religious language and rational discourse. She is the headmistress and executive director of the Pridgen Ninja Jedi Training Academy for Precocious Children, and she deeply regrets allowing her sons to name their homeschool.

One Nation, Another Religion?

by Rachel Pridgen

Having grown up in Southern California during the Reagan years nothing would have led me to challenge the assumption that all Americans believed in God. We had strong Evangelical leaders and it was evident that God had manifestly blessed America and allowed us to thrive and flourish. To be sure, there were two kinds of Americans: those with vibrant belief and those with apathetic belief. But Americans with no belief? Those existed in the same way ogres, evil wizards, and traitors existed—in a mythical ghetto where we were free to abhor them without actually encountering them. Born into a Christian family during the growth spurt of the religious right, I was unaware of the existence of secular Americans.

“Growing up” for me therefore meant (among many other things) encountering the reality of free thought in America and the humanity that lies behind it. As I asked more questions and my faith failed, I was amazed to find a sizable and thriving secular community beyond my believer bubble.

David Niose, President of the American Humanist Association and Vice President of the Secular Coalition for America presents a new book full of information on secular Americans. Nonbeliever Nation provides a framework for understanding the role of secular Americans, the obstacles they face, and their vision for the future. Niose’s treatment, while not exhaustive, ably maps the American secular experience sociologically and demographically. He begins with demographic data revealing a population in transition. Secularity in America is growing through a change in both belief and identity. It is still an unfortunate reality that disbelief is marginalized in the United States. Open secularity is still not as common as it should be based on the numbers. Tellingly, 81% of Americans report a belief in a divinity, but only 1.6% identify as atheist or agnostic. This means approximately 1 in 6 Americans don’t believe in a divinity, but are unwilling to identify as a non-believer.

The social stigma attached to atheism causes many to remain unidentified regardless of actual belief. This is particularly interesting if one looks at the results of increased religiosity. It would appear that we are not any better off for all of our high rates of fundamentalist beliefs. We have one of the highest homicide rates of all industrialized countries, and Niose provides quotes and statistics to show that “higher rates of belief in and worship of a creator correlate with higher rates of homicide, juvenile and early adult mortality, STD infection rates, teen pregnancy and abortion.” It turns out that belief in God does not necessarily help us to be more moral, and in fact may result in just the opposite. Despite this information, surveys show that atheists remain the most distrusted minority in America, surpassing even rapists and pedophiles.

Niose uses his opening chapters to establish the fact that secular Americans were not always so closeted. In fact, it came as a surprise to many that the Religious Right gained such a strong foothold in American politics. Many simply believed that religious fundamentalism would decline as scientific advances and critical thinking skills increased. This prediction has proven false as the Religious Right has maintained its political clout through heavy marketing strategies, use of emerging technology to reach new markets, and the marginalization of secular culture. Religious conservatives also made extensive use of revisionist historians in order to promote the idea of a conservative Christian tradition in the founding and history of America. Though there are more complete treatments of the secular tradition in America to be found, Nonbeliever Nation provides an excellent overview without getting dragged away from its main focus.

On the matter of secularity and morality, for example, after addressing the evidence that increasing religiosity has not made America a more moral nation than its less religious peers, Niose provides a succinct, accessible overview of the concepts of evolved morality and the benefits of adherence to social norms. For those unfamiliar with the concepts, this presentation is extremely easy to understand, and for those who have already explored these concepts, Niose communicates a sizable amount of complex information without overloading readers.

After laying this sturdy framework, attention is turned to the current problems facing secular Americans. The most pressing problem is not that religion exists or that people believe in God, but that so many of these religious beliefs are being made a matter of public policy. Niose is quick to point out that individual belief is not nearly as problematic as the policies that come out of these beliefs. Unfortunately, the Religious Right views even attempts at religious neutrality as hostile attacks, and are willing to throw large quantities of resources at those who will create more Christian policies. This becomes a problem for secular Americans when the goals of the Religious Right involve anti-intellectualism, revision of textbooks, promotion of public prayer, and discrimination against those without a belief in god.

Now the good news: secular Americans are emerging. Activism is on the rise, people are identifying and organizing in order to influence sound policy, and student activism especially is growing by leaps and bounds. Thanks in large part to the Internet, communities of secular Americans are uniting and working together to make themselves known and heard. College students across the nation are working together to form student alliances, and even high schools are beginning to see the formation of secular student groups. Despite opposition, these groups can legally meet thanks to rights that were originally won by religious groups attempting to gain access to students, so there is a bit of quid pro quo there!

Niose observes that the secular movement is learning a lot from the work of other minority groups, most noticeably, the LGBT movement, which has made great strides in recent years by advocating an identity campaign. Encouraging their members to openly identify and make themselves known has allowed them a public presence, the ability to organize, and a common ground for influence. Niose believes that secular Americans need to adopt this strategy as well in order to move forward and enable change. Unless secular Americans make their presence known, they have little hope of influencing public policy or changing public perceptions. But as Niose emphasizes, this is happening, especially among young people. There is hope that change is imminent. With solid education and awareness, more non-believers will be accepted within the political sphere.

The largest remaining need is that of a solid secular community. Niose states that “religious institutions offer tradition, cultural continuity, and a place to find peace of mind through ritual, meditation, and contemplation. As long as this is not infringing on anyone else’s rights, this can be all good.”

To that end, Alain de Botton offers Religion for Atheists, an interesting read that is sure to stir up conversation and controversy. His thesis is simple: Religion does some things well, and the secular community should unapologetically steal those things. It is de Botton’s goal to create a secular culture with religious (though not supernatural) influences. Though the number of atheists attending Unitarian Universalist churches bears testimony to the validity of some of his claims, de Botton fails to recognize that adding ritual and organization to secular communities does little to avoid the structural problems inherent in religious groups and is unlikely to provide enough positives to outweigh the negatives of dogmatism, propaganda, and various other issues.

De Botton asserts that the creation of community is the easiest and most obvious of the areas in which religions excel. Houses of worship are gathering places for people of varying ages and social classes. Once a week, the faithful are encouraged to set aside their personal differences in order to affirm common beliefs as members of a group. While many will argue that the reinforcement of beliefs is unnecessary, it is hard to argue with the way religions provide an instant social network for their members.

The reinforcement of beliefs is also something that de Botton believes non-believers could adopt. Religion for Atheists points to the methods that churches use to both transmit and affirm beliefs as valuable tools for educators. He argues that while higher education teaches us how to make a living, it doesn’t provide a framework for living well. Churches teach application of values found in its music, writings, and art. They excel at teaching through ritual and repetition. And the best churches employ strong orators who know how to command an audience and draw people in to their topic.

Art and architecture also receive extensive time, though there are many who would criticize the extremes of de Botton’s examples. Religions have historically been very good at using art as propaganda. Not only do they create and commission art, they provide a ready-made framework for interpreting it. The church tells its members exactly how to think and feel about the art they provide. The non-religious do this as well, only it’s called “advertising.” De Botton goes on to say that we should attempt to provide similar interpretive frameworks within our museums, organizing art by topic, emotion or general feeling instead of chronologically or by genre. While it’s an interesting idea, I think it would effectively cut off many observers from their own interpretations.

And this is the problem with many of the suggestions offered in Religion for Atheists. Establishing community is a pretty good idea. Establishing restaurants where patrons are seated with random strangers and instructed to discuss their deepest fears is not a very good idea. Encouraging kindness, creating more beautiful spaces, and finding meaning in life are all great. The idea that we need to establish secular organizations to do these things in ritualistic ways is probably not necessary.

There are other topics where de Botton may find even greater opposition. One chapter claims that the non-religious don’t have enough reminders of the transcendent and that they lack big picture perspective. That has simply not been my experience, nor do I find it to be the experience of the nonbelievers I know. In fact, if anything it seems that most skeptics are more aware of their own insignificance and the fragility and brevity of life, along with the transcendent feelings one gleans from a cosmological and evolutionary perspective.

Both of these books provide valuable food for thought. Niose’s examination of the secular situation in America, its history, and suggestions for the future give hope that secularity will continue to grow and suggest practical ideas for participation in the movement. Due to my recent deconversion, De Botton should have a devoted fan in me. I feel the same pangs toward ritual and the things that the religious community did well as far as establishing community. I even feel the occasional desire to listen to a rousing sermon, though I find debates and lectures to be far more interesting and educational. Unfortunately, I found myself rejecting most of his suggestions. The good news: de Botton’s ideas are just crazy enough to get people talking. While discussing some of the more ridiculous options, we can evaluate whether secular America truly is missing anything, determine what it is, and perhaps come up with ways to fill that need. While it is true that the secular community often throws out the baby with the bathwater when it comes to avoiding similarities to religion, I’m not sure we need to start holding secular baptisms just yet.

Skeptical perspectives on faith, atheism and morality…

-

The Faith of Our Forefathers

The Faith of Our Forefathers

by Frank Miele -

Skeptic magazine Senior Editor Frank Miele begins by showing how, when religious fundamentalists call for a return to moral standards, they hold the founding fathers up as exemplars of whatever viewpoints they are seeking to “reestablish” in society. Miele shows how inaccurate this picture is with a slide tour of religion and politics as the revolutionary leaders really saw them. After seeing this lecture you can answer the claims of conservatives and fundamentalists that American was founded as a Christian nation… Order the lecture on DVD.

-

The Living Without Religion

The Living Without Religion

by Paul Kurtz -

One of America’s foremost expositors of humanist philosophy, Paul Kurtz shows how we can live the good life filled with morality, commitment, and dedication, without having to depend on the existence of a higher being. Drawing upon the disciplines of the sciences, philosophy, and ethics, Kurtz also offers concrete recommendations for the development of the humanism of the future. An entire section of the book is devoted to the careful definition of religion, which clearly demonstrates than an authentic moral life is possible without religious belief… Order the book.

-

Science and Religion

Science and Religion

Skeptic magazine Vol. 8 No. 2 -

In this issue: Are Science and Religion Compatible?; Faith of the Fatherless: The Psychology of Atheism; Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life, by Stephen Jay Gould; The Natural & the Supernatural: Science, Religion & their Defenders; Finding Darwin’s God: A Scientist’s Search for Common Ground Between God and Evolution; Holy Man, Holy War, Wholly Fiction; Skeptics and True Believers: The Exhilarating Connection Between Science and Religion…

Order the back issue.

-

Reinventing the Sacred: A New View

Reinventing the Sacred: A New View

of Science, Reason & Religion

by Dr. Stuart Kauffman -

In this controversial lecture based on his new book, the world-renowned complexity theorist Dr. Stuart Kauffman argues that people who do not believe in God have largely lost their sense of the sacred and the deep human legitimacy of our inherited spirituality, and that those who do believe in a Creator God, no science will ever disprove that belief. Kauffman believes that the science of complexity provides a way to move beyond both reductionist science and dogmatic theology to something new: a unified culture where we see God in the creativity of the universe, biosphere, and humanity…

Order the lecture on DVD.

-

How I Lost My Faith Reporting on Religion

How I Lost My Faith Reporting on Religion

in America—and Found Unexpected Peace

by William Lobdell -

William Lobdell’s journey of faith—and doubt—is one of the most compelling spiritual memoirs of our time. Lobdell became a born-again Christian in his late 20s and the Los Angeles Times asked him to write about faith. While reporting on hundreds of stories, he witnessed a disturbing gap between the tenets of various religions and the behaviors of the faithful and their leaders. He investigated religious institutions that acted less ethically than corrupt Wall Street firms. He found few differences between the morals of Christians and atheists. As this evidence piled up, he started to fear that God didn’t exist. He explored every doubt, every question—until, finally, his faith collapsed… Order the lecture on DVD.

Announcing The Amaz!ng Meeting 2012

Southpoint Hotel & Casino, Las Vegas, NV

July 12–15, 2012

THE AMAZ!NG MEETING (TAM) is an annual celebration of science, skepticism and critical thinking. People from all over the world come to TAM each year to share learning, laughs and the skeptical perspective with their fellow skeptics and a host of distinguished guest speakers and panelists.

The James Randi Educational Foundation (JREF) has hosted its annual Amaz!ng Meeting since 2003 as a way to promote science, skepticism and critical thinking about paranormal and supernatural claims to the broader public. TAM has been held in Las Vegas, NV since 2004 and has become the world’s largest gathering of like-minded science-advocates and skeptics.

With yet another incredible lineup of speakers, hands-on workshops, and entertainment, this is sure to be an Amaz!ng Meeting you won’t want to miss! Check out the entire program, and follow @jref on Twitter for the latest #TAM2012 news and announcements.

The Secrets of Mental Math: The Mathemagician’s Guide to Lightning Calculation and Amazing Math Tricks

TEACHERS AND PARENTS, BRING YOUR STUDENTS AND KIDS to see the famous lightning calculator and mathemagician Art Benjamin demonstrate simple math secrets and tricks that will forever change how you look at the world of numbers. Get ready to amaze your friends—and yourself—with incredible calculations you never thought you could master, and learn how to do math in your head faster than you ever thought possible, dramatically improve your memory for numbers, and—maybe for the first time—make mathematics fun. Dr. Benjamin will teach you how to quickly multiply and divide triple digits, compute with fractions, and determine squares, cubes, and roots without blinking an eye. No matter what your age or current math ability, Dr. Benjamin will teach you how to perform fantastic feats of the mind effortlessly. This is the math they never taught you in school.

TAGS: Art Benjamin, fast math calculations, math in your head, mathemagics12-06-06

In this week’s eSkeptic:

NEW ON MICHAELSHERMER.COM

The Science of Righteousness

Why are we so predictable and tribal in our politics? In Michael Shermer’s June “Skeptic” column for Scientific American, he explains how evolution helps to explain why parties are so tribal and politics so divisive, arguing for the necessity of competition in creating a “livable middle” ground for society.

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

A Weekend of Woo (Or why I love the Esalen Institute)

Michael Shermer recounts his experience at the Esalen Institute this past weekend where he gave a 3-day workshop on “Science, Spirituality, and the Search for Morality and Meaning.”

Lecture this Sunday at Caltech:

Dr. Art Benjamin

The Secrets of Mental Math: The Mathemagician’s Guide to Lightning Calculation and Amazing Math Tricks

SUNDAY, JUNE 10, 2012 AT 2 PM

Baxter Lecture Hall

Teachers and parents, bring your students and kids to see the famous lightning calculator and mathemagician Art Benjamin demonstrate simple math secrets and tricks that will forever change how you look at the world of numbers. Get ready to amaze your friends—and yourself—with incredible calculations you never thought you could master, and learn how to do math in your head faster than you ever thought possible, dramatically improve your memory for numbers, and—maybe for the first time—make mathematics fun. Dr. Benjamin will teach you how to quickly multiply and divide triple digits, compute with fractions, and determine squares, cubes, and roots without blinking an eye. No matter what your age or current math ability, Dr. Benjamin will teach you how to perform fantastic feats of the mind effortlessly. This is the math they never taught you in school.

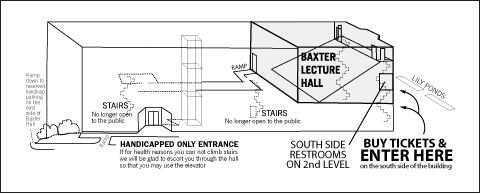

Admission policy for Baxter Lecture Hall

Due to security concerns, Baxter Hall will be locked and the audience will be admitted only through the doors on the South side of the building by the lily ponds. If, for medical reasons, you cannot climb the stairs to the hall on the 2nd floor, someone at the main entrance (located in the middle of the West side of the building) will escort you to the elevator.

Tickets

First come, first served at the door. Seating is limited. $8 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $10 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

Spongelab: A Global Science Community

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 184

The landscape of education is changing at a pace which might be considered ‘warp speed.’ With tools like Google and Wikipedia, along with a more tech savvy population, new hurdles and challenges face professors and teachers at all levels. Computerized, online media is where many are turning for good resources and content.

In this episode of Skepticality, Derek sits down with Dr. Jeremy Friedberg, the founder and president of Spongelab, an online community which bills itself as “A Global Science Community.” The website is full of resources, digital media, educational computer games, and lesson plans—all of which are free for any educator to use to further enhance their curriculum, and to get students excited about learning the beauty of science and the real world. Find out more about how one company is making sure that science and the real world are communicated in the most effective manner in our modern, cyber-enhanced world.

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, we present a gem from one of the early issues of Skeptic magazine in which Phil Molé examines some of the teachings and philosophy of Deepak Chopra, and reminds us of the power of science to enlighten. This article appeared in Skeptic magazine volume 6, number 2 (1998).

Phil Molé has a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from DePaul University, where he minored in biology and mathematics. He earned a Masters in Public Health from the University of Illinois at Chicago, and works at an environmental consulting company in Elmhurst, Illinois.

Deepak’s Dangerous Dogmas

by Phil Molé

Through much of history, religious faith was a strong component of medical practice. Diseases were often thought to result from blockages in the body’s flow of vital forces, or from possession by malevolent spirits. Eventually, scientific medicine far surpassed efforts of faith healers, so the latter was made to yield authority to the former.

Occasionally, however, vestiges of the old system creep back in. The current attention given to mind-body medicine — and its most prominent practitioner, Deepak Chopra — testifies to this fact. The author of 19 books, Chopra gives seminars around the world, releases numerous videotaped lectures, and has his own line of herbs and aromatic oils. He also boasts of an impressive celebrity clientele, including Demi Moore, Elizabeth Taylor, George Harrison, and Michael Jackson. Former Good Morning America anchorwoman Joan Lunden even described him as a “huge influence” on her life (Lunden, 20).

The content of Chopra’s philosophy is often obscured by logical inconsistencies, but it is possible, nonetheless, to identify its key components. First, he views the body as a quantum mechanical system, and uses comparisons of quantum reality with Eastern thought to guide us away from our Western, Newtonian-based paradigms. Having accomplished that, he then sets out to convince us that we can alter reality through our perceptions, and admonishes us to appreciate the unity of the Universe. If we allow ourselves to fully grasp these lessons, Chopra assures us, we will then understand the force of Intelligence permeating all of existence — guiding us ever closer to fulfillment. Each component of this philosophy has serious flaws, and requires individual analysis.

The Great Quantum Paradigm Shift

To understand why Chopra is trying to nudge us Eastward in our philosophies, we must first understand the nature of mystical thought, and its rise to prominence in American culture. Mysticism, of course, has been part of our intellectual heritage for thousands of years, originating with ancient Greek thinkers such as Plato and Heraclitus. Eastern religions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Taoism expressed similar sentiments, in more developed and poetic forms. There are many varieties of mysticism, but all of them share the four characteristics elaborately described by Bertrand Russell in his classic essay “Mysticism & Logic.” All mystics believe in sudden insight — a revelation of irrefutable knowledge unavailable to the senses; they believe in the oneness of all matter, and the unreality of opposites; they deny the reality of time, since the “past” and the “future” are merely opposite terms resulting from deluded human thought; and they deny the existence of evil.

In 1975, mysticism received its first forceful endorsement from a member of the scientific community. Physicist Fritjof Capra, in his enormously successful book The Tao of Physics, speculated elaborately about the similarities between the science of the subatomic world and the philosophy of Eastern sages. Capra believed these similarities could not be due to chance alone and claimed that the wave particle duality of matter, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, the equivalence of mass and energy, the Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics and Einstein’s relativity theories were specific affirmations of mystic principles. Like any mystic worth his salt, he developed this theory through sudden insight:

I was sitting by the ocean late one summer afternoon, watching the waves rolling in and feeling the rhythm of my breathing, when I suddenly became aware of my whole environment as being engaged in a gigantic cosmic dance I saw cascades of energy coming down from outer space, in which particles were created and destroyed in rhythmic pulses; I saw the atoms of the elements and those of my body participating in this cosmic dance of energy; I felt its rhythm and I heard its sound, and at that moment I knew that this was the dance of Shiva, the Lord of the Dancers worshipped by the Hindus (Capra, 11).

To his credit, Capra distinguished between the physical laws pertaining to subatomic entities — and objects traveling near the speed of light, and the physical laws pertaining to boring, macroscopic classical matter — like us. He merely stated that 20th century physics has shown us a different side of reality, and suggested we should change not only our scientific paradigms, but also our social ones, to correspond more closely with the findings of Planck, Einstein and Bohr. This, of course, is still a rather flawed thesis, as I will explain shortly.

Chopra, however, takes a stance that makes Capra look staunchly conservative. In essence, he asserts that our bodies should no longer be regarded as solid mass in the strict Newtonian sense, because they’re made of atoms, which are governed by the laws of quantum mechanics. Therefore, he argues, we must abandon our old views of our bodies, because they do not represent our true reality. “This way of seeing things — the old paradigm,” he tells us in Ageless Body, Timeless Mind, “has aptly been called the ‘hypnosis of social conditioning,’ an induced fiction in which we have collectively agreed to participate (4).” There’s no qualification of meaning attempted here: Chopra is saying the Newtonian-based image of our bodies is wrong, and the quantum-mechanical image of our bodies is right. Since he, like Capra, finds profound similarities between quantum mechanics and mystical thought, the maxims of Eastern sages are automatically fashioned into the guideposts of our life.

Examined credulously, Chopra’s argument seems persuasive. There certainly seems to be some resemblance between, say, the Buddhist assertion that matter and empty space are the same, and the fact that atoms, “the building blocks of matter,” are mostly empty space. Yet, arguments based on superficial logic are not only persuasive, but also dangerous, since they may lead us into errant patterns of thinking. This is the nature of Chopra’s argument, which finds connections where there may be none, and recklessly superimposes the laws of one level of reality on the matter of another.