12-01-11

In this week’s eSkeptic:

A DEBATE BETWEEN

Christopher Hitchens & Kenneth Miller on:

“Does Science Make Belief in God Obsolete?”

In last week’s eSkeptic, we presented Christopher Hitchens’ answer to the question “Does Science Make Belief in God Obsolete?” This week, we present the same question in the form of a debate between Christopher Hitchens and Kenneth Miller. Hitchens (self-proclaimed anti-theist and author of God Is Not Great) and Kenneth Miller (a pro-evolution Christian and author of Finding Darwin’s God) are worlds apart both by profession and belief, and yet both have brilliant minds for dissecting arguments both scientific and philosophical. First, Hitchens comments on Miller’s essay, followed by Miller’s response, and then the remaining dialogue between the two. This debate was edited by Michael Shermer for the Templeton Foundation’s Big Question Essay Series.

A debate between

Christopher Hitchens & Kenneth Miller

edited by Michael Shermer

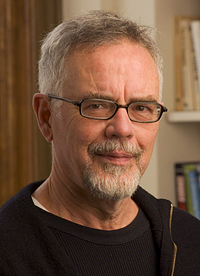

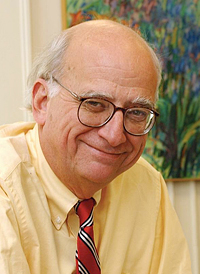

Christopher Hitchens (1949–2011). Photo by Christian Witkin.

Christopher Hitchens: I am not scientifically certified in any field, but when I read a “creationist” account of an Eden-based evolutionary fairy-story, I consider myself sufficiently qualified to understand and to refute the mental process by which it is argued. On the other hand, I do possess some small qualifications in the world of language and its relationship to cognition and I have to confess that I simply cannot make sense of a single one of your most important assertions or (perhaps I should better say) avowals.

What does it mean to say, “The Deity they reject so easily is not the one I know”? If you have such an extraordinary acquaintanceship, or source of information, is it only humility that keeps you confined in the small compass of Rhode Island? You go on to state that a rather intriguing and immense question (why is the world “bursting” with so much bio-diversity?) has in fact a rather obvious answer. You write: “To a person of faith, the answer to that question is God.”

Well, I hope I may be excused if I state that I already knew about the things that faith can apparently cause people—without a rag of evidence—to believe. But is this same reply also the answer to the question: “why have 99.9 per cent of all known species on our planet become extinct?” If so, then god—I don’t capitalize my concepts—explains everything and nothing with equal ease.

This same tenacious addiction to tautology and non-sequitur must be the explanation for the latter part of your essay, in which you accuse atheists of trying to make god “an ordinary part of the natural world” (no we don’t: the pantheists and the Paleyites do that). You make the circular assertion that god is “the reason for nature, the explanation for why things are” and the incoherent proposal that “He is the answer to existence, not part of existence itself.” I have heard Zen koans uttered with more articulation. It would be unkind to ask you how you proceed from such deistic assumptions to your theistic ones—the Resurrection, for example. Why do you believe in such things? Do you believe that you have a superior access to the numinous, and because such beliefs—in common with all other superstitions—are not subject to direct disproof or falsifiability? If so, you will, by the same token, have to accept my deeply-held belief that such opinions are the moral and verbal equivalent of white noise.

Before any further damage to the good name of science is done, let me point out that it is perfectly absurd to say that there is a “scientific faith” which assumes that all matters are reducible to the immediately comprehensible. I would briefly cite J.B.S. Haldane’s observation that the universe is not just queerer than we imagine, but queerer than we can imagine. I might add Einstein’s remark that the miracle is that there are no miracles: that the natural order is in fact harmonious and not to be interrupted by capricious supernatural interventions. If that doesn’t take care of deism, it takes care of theism—and it’s religion we are talking about in this debate. Professor Miller, you appear to me to fail the elementary test of being able to say what your opponents are talking about. But then, by your absurd use of the term “validate” in the closing sentence of your essay, you would seem to have no idea what you yourself are talking about, either.

Kenneth Miller

Kenneth Miller: I must confess that I was surprised by the tone and the content of your writing, and especially by your eagerness to move the discussion away from science. You invoked history, writing that revelation came at the wrong time and to the wrong people. Apparently a proper God would have avoided “gaping peasants,” and delivered his message instead to high table at Oxford. You deliberately misread my reference to personal belief as a claim of special revelation, and even found time to ridicule a tiny American state—ironically, the very one which first gave birth to the concept of religious freedom. Why such departures from the issue at hand?

Perhaps it is because you sense the inherent weakness of your argument. Your essay cited three scientific points, which, you were confident, would have kept us from “adopting monotheism.” Ironically, in essence these were: 1) our species had a beginning, 2) the universe had a beginning, and 3) our existence will come to an end. Last time I looked, each of these was actually a teaching of the great monotheistic faiths. So much for the profound contradiction you sought.

You tip your hand when invoking extinction as a problem for faith, having fixed your arrow on nothing more sophisticated than an “Eden-based evolutionary fairy-story.” You declare yourself, just as young-earth creationists do, unable to stretch the cloth of Genesis around the Big Bang, mass extinction, and human evolution. But scripture reflects the flawed cosmology of its age, just as one might imprint today’s imperfect and incomplete science on the specifics of either your disbelief or my faith. Finding that old conceptions of nature are wrong, just as many of today’s theories surely are, does not even begin to invalidate the religious message that we live in a universe reflecting the will and rationality of a creator. You say that the natural order is harmonious. I agree. At issue is the source of that harmony.

You say that the grand sweep of the cosmos makes “pathetic nonsense” of the notion that human existence is part of a plan, but on what scientific basis do you make that judgment? In reality, the potential for human existence is woven into every fiber of that universe, from the starry furnaces that forged the carbon upon which life is based, to the chemical bonds that fashioned our DNA from the muck and dust of this rocky planet. Seems like a plan to me.

I was particularly impressed—but not in a good way—by your misuse of Einstein. In saying that there are “no miracles,” he was not ruling out the divine, but speaking to the scientific comprehensibility of nature. Einstein also said there are two ways to live: as though nothing is a miracle, or as though everything is. I choose the latter, and clearly, so did he. Finally, you say that I am an “opponent” who simply does not know what you are talking about. Mr. Hitchens, I regard you as a friend, not an opponent, and would suggest that the real problem is I understand what you are talking about all too well.

Hitchens: To take these points in reverse order: Albert Einstein took a Spinozist worldview that excluded the idea of a personal god or a deity that intervened in human affairs. The natural order does not respond to prayer or propitiation: it maintains its extraordinary regularity. This may not rule out a certain non-specific deism or pantheism, but it does make nonsense of the idea of a god to which human beings can address themselves.

The argument from design has seldom been stated more sloppily than in the “grand sweep” paragraph that (in ascending order) undergirds this misreading of Einstein. Pray tell, is it all designed, or just the apparently harmonious bits? The impending collision between our galaxy and Andromeda: part of the plan or not? A series of lifeless failed planets in our own solar suburb: good design or random coincidence? As with every other such invocation, the fans of the designer must convict him either of a good deal of waste and fumbling or a great deal of cruelty and indifference, or both.

It is cheap to compare me to a young-earth creationist just because I suggest that one must choose between “scripture” and science. The former does indeed reflect “the flawed cosmology of its age,” but that is precisely because it is a work of man and not a work of a deity. Which was my original point.

I cannot see how this insistence on an apparently designed harmony can be squared with your original assertion that god is “the answer to existence, not part of existence itself” or with your scorn for the idea that god is “an ordinary part of the natural world.” Is he or isn’t he the key to the natural order, or at any rate a dynamic element in it? I can understand you avoiding my question about resurrection, but if you want to stay focused on science then you can’t have this both ways.

It’s good of monotheists to accept that things have beginnings and ends. (“By god, sir,” as Samuel Johnson said in a slightly different connection, “they had better”.) I suppose one difference here is the eschatological one, or the way in which religion looks forward to the end. That important distinction to one side, the materialist view is simply that science can provide us, and indeed has provided us, with explanations for the origin and the terminus, of our cosmos and our species, that require no supernatural element. If this is not a scientific refutation of faith (which it isn’t, since faith isn’t susceptible to such procedures) it makes faith and science look increasingly hard to reconcile.

I was ridiculing you and not Rhode Island, as any careful reader will see. And yes, I do think that the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary and other apparitions ought at least once in human history to have shown themselves to people who were able to read and write, who were not terrified of demons and ghosts, and who possessed the ability to test evidence in the crucible of experiment. It hasn’t happened yet and I predict that it isn’t going to happen, either. Nonetheless, the witchdoctors and shamans can always count on the credulity of second-and-third-hand witnesses, descending to tenth-and-twentieth hand, some of whom will sadly claim to base their beliefs on scientific method.

Miller: You know, Christopher, I think we’re making progress. In your invocations of Einstein and Spinoza there is a grudging, if indirect, deference to the argument in my original essay—specifically, that faith “includes science, but then seeks the ultimate reason why the logic of science should work so well.” In each of your contributions to this dialogue, you’ve dismissed this as implying nothing more than deism, as if that alone was sufficient to refute it. As you well know, it is not.

Classic deism involves a God who is creator and prime mover, yet uninvolved in the affairs of his universe. But apply some logic here. By what principle would a God, capable of creating such vastness, be constrained from intervening in its affairs? Clearly, that restraint could only come by choice, and given such power, it would have to be a willing choice. The distinction between theism and deism, therefore, is really a claim about the personality of God, and the nature of his actions (or lack of same) in our created world. Earlier, I wrote that the atheist places God within the realm of science to investigate and test. The arguments you raise against scripture and reports of the miraculous take this form exactly, and that is also why they fall short—because they consider God to be a part of nature rather than nature’s cause. I do wonder what sort of God would meet your tests for clarity of teaching and evidence of existence, and I would love to hear your answer.

I accept that your first response was an attempt at personal ridicule. However, I wonder why you resort to such tactics if the logic of your case is so compelling. You note sarcastically that it is “good of monotheists to accept that things have beginnings and ends.” Can you possibly be serious, when Abrahamic monotheism has always spoken of ends and beginnings? As you acknowledge, science has indeed given explanations for “our cosmos and our species that require no supernatural element.” On that point you and I agree. But this means only that science has now confirmed nature’s sufficiency to fulfill the promised work of its creator.

You ask if all is designed, including galactic collisions, “failed planets,” and the extravagant waste of nature. Yet by what rubric do you know the “purpose” of galaxies and planets, in order to pronounce them “failed?” There is waste and death in nature and the cosmos, but there is something else as well. Amid the material from which you draw the bleak conclusion of purposeless chaos, there are the very laws and elements that make evolution (and humanity) possible. A great biologist, whom we both admire, once wrote that there was “grandeur in this view of life,” and science has done nothing since to set that judgment aside. A world of “endless forms, most beautiful and most wonderful” is the one in which we find ourselves, and I believe there is a reason for that.

Hitchens: That there might have been a “mind” at the beginning of the cosmos does not in the least entail that there still is one, or that its abstention from intervention in human affairs is conscious. (If the mind took the form of an intelligent and self-conscious “god”, as Lucretius pointed out, it would obviously wish to stay out of our petty quarrels and strivings.) And this mind would also need to have been created or inspired by still another mind, as in turn would that mind. No wonder that Christians prefer to start speaking about “mysteries” at this point.

Incidentally, are you a Christian? I have no idea which religion you do or do not believe in. Do you think that this eternal mind waited until two thousand years ago, then donated a son for a human sacrifice and thus enabled us to purge ourselves from sin? Or do you prefer to think that Mohammed is god’s messenger, or that the eternal mind has made a covenant with one special tribe? With atheists, it is always possible for our opponents to know and understand (if they choose to) what we believe (or do not believe). With religious people it is possible to spend a long time in discussion without ever discovering precisely what role they believe the supernatural to play in our lives. And no two claims are ever quite the same—further proof that the whole religious enterprise is improvised by primates.

To answer your challenge: if I had faith I would not presume to act or think as if god owed me an explanation. Surely that is the point of faith to begin with: to fill the unbridgeable void between evidence and the entire lack of it. That’s why I consider it the most over-rated of the virtues.

Miller: As we conclude, I am struck by your careful avoidance of our question—whether science makes belief in God obsolete. Instead you puzzle over my religion (I’m a Catholic) and invoke the old standbys: scripture is unreliable, faiths contradict, miracles are delusional fabrications, and God’s reported interventions in human affairs make no sense (to you). You dismiss a “mind” as first cause by invoking an infinite regression of minds—ironically unaware that your own view requires exactly that—an infinite regression of natural causes. A theist sees the logical problem here, but apparently you do not.

You avoided my direct question (to you, a “challenge”) of what might convince you of God’s reality. You wrote, in effect, that no evidence would do—a very fair summary of your views on this issue, I admit.

In the end you have no answer to why science works, why the physical logic of natural law makes life possible, or why the human mind is able to explore and understand nature. And I agree that there is no scientific answer to such questions. That is precisely the point of faith—to order and rationalize our encounters with the world around us. Faith is human, and therefore imperfect. But faith expresses, however poorly, a reality that includes the scientific experience in every sense, and therefore has become more relevant than ever in our scientific age. ![]()

Skeptical perspective on the Big Questions…

-

Origins & The Big Questions

Origins & The Big Questions

Conference 2008 (5 Part Set)

with Donald Prothero, Leonard Susskind, Paul Davies, Sean Carroll, Christof Koch, Kenneth miller, Nancey Murphy, & Michael Shermer -

Today, there is arguably no hotter topic in culture than science and religion, and so much of the debate turns on the “Big Questions” that involve “origins ”: the origin of the universe, the origin of the “fine-tuned” laws of nature, the origin of time and time’s arrow, the origin of life and complex life, and the origin of brains, minds, and consciousness. Now, science is making significant headway into providing natural explanations for these ultimate questions, which leaves us with the biggest question of all: “Does science make belief in God obsolete?” we have assembled some of the world’s greatest minds to discuss some of the world’s greatest questions. In 2008, the Skeptics Society held a conference wherein we assembled some of the world’s greatest minds to discuss some of the world’s greatest questions…

READ more about this conference and order the 5-part DVD set.

OR, order single DVDs: part 1 | part 2 | part 3 | part 4 | part 5

-

The Evolution of God

The Evolution of God

by Robert Wright -

From the Stone Age to the Information Age, Robert Wright unveils an astonishing discovery: there is a hidden pattern that the great monotheistic faiths have followed as they have evolved. Through the prisms of archaeology, theology, and evolutionary psychology, Wright’s findings overturn basic assumptions about Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and are sure to cause controversy. He explains why spirituality has a role today, and why science, contrary to conventional wisdom, affirms the validity of the religious quest. And this previously unrecognized evolutionary logic points not toward continued religious extremism, but future harmony. READ more and order the DVD.

-

Why People Believe in God

Why People Believe in God

by Michael Shermer -

Shermer presents data from an empirical study of 10,000 Americans — why do people believe in God? Why is belief in God increasing, not decreasing as predicted? How the fact that we live in an age of science influences the reason people give for their faith. How people assume others believe in God for different reasons than they do. The psychology of rationalizing beliefs arrived at for non-rational reasons.

READ more and order the DVD.

Other Books & Lectures on Evolution & Creationism

Our online store has a wide selection of books and lectures (at Caltech) on the topics of evolution and creationism.

Tim Farley illustration by Neil Davies. Card design by Crispian Jago.

2011: A Year in Review

with Tim Farley

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 173

This week on Skepticality, host Derek sits down with Tim Farley to reflect on what happened in the skeptical world over the course of 2011 and ponder what is in store for 2012. Tim Farley is the creator of the website Whats the Harm (a catalog of actual cases of people suffering physical, medical, financial or other harm because of their beliefs in concepts not supported by science) and Skeptic History (a collection of historical dates of interest to skeptics).

OUR ANNUAL FUNDRAISING DRIVE IS ON NOW

Help Send Skepticism 101 into the World!

- Click here to read our new plan to take Skepticism to the next level!

- Click here to make a donation now via our online store.

Monthly Recurring Donation Options Now Available

We encourage you to choose the monthly recurring donation option. Simply tell us how long you want your donation to recur (using the drop-down menu on the donation page) and we’ll set up automatic withdrawal for the amount you select.

Just for considering a donation, check out our free PDF download

created by Junior Skeptic Editor Daniel Loxton.

12-01-04

In this week’s eSkeptic:

- Junior Detectives Club : Free Skeptics Mix Tape “Bonus Track”

- Lectures at Caltech: Announcing Our Spring 2012 Lectures

- Follow Michael Shermer: God, Guns, and Artificial Intelligence

- Feature article: CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS on:

“Does Science Make Belief in God Obsolete?” - Fundraising Drive on Now: Skepticism 101 available to the world!

Junior Detectives Club —

Free Skeptics Mix Tape “Bonus Track”

TO START 2012 OFF RIGHT, we’re pleased to share a small gift from Junior Skeptic: the upbeat and apt song, “Junior Detectives Club” from science-themed children’s musician Monty Harper. We’ve added “Junior Detectives Club” as a bonus track for the the kid-friendly Skeptics Mix Tape 2009 project.

Harper recorded this song in 2007 for the Collaborative Summer Library Program (a reading program shared by many states) and for his album Get a Clue. “I wanted it to sound like a real club, singing a song to open their meeting,” Harper told eSkeptic. To achieve that sound, he enlisted the help of Oklahoma music teacher Rana McCoy and her children’s voice group, The Center Stage Singers.

The result is a light-hearted skeptical manifesto for kids, performed by kids—and it’s yours to enjoy.

Monty Harper writes award-winning children’s songs about science, reading, and creativity. His audiences laugh, clap, sing, wiggle, shout, roar, giggle, jump, hoot, pop, snap, and most of all… think! To learn more about Monty Harper visit his website, or check out his latest album, Songs From the Science Frontier, on iTunes.

Announcing the Spring 2012 Season

of Our Distinguished Lectures at Caltech

MARK YOUR CALENDAR! The Skeptics Society is pleased to announce another season of our Distinguished Lecture Series at Caltech.

All lectures are in Baxter Lecture Hall on a Sunday at 2 pm with the exception of the Monday, March 19 lecture which will be held at 7:30 pm and the Sunday, March 25 debate which will be held in Beckman Auditorium at 2 pm. All events include an author book signing. First up…

- Why We Believe in God(s): A Concise Guide to the Science of Faith

with Dr. Andy Thomson

Sunday February 12, 2012 at 2 pm - Abundance: Why the Future Will Be Much Better Than You Think

with Dr. Peter Diamandis

Saunday, February 26, 2012 at 2 pm - The Creative Destruction of Medicine: How the Digital Revolution

Will Create Better Health Care

with Dr. Eric Topol

Sunday, March 11, 2012 at 2 pm - Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, & Politics in the Book of Revelation

with Dr. Elaine Pagels

Monday, March 19, 2012 at 7:30 pm - The Great Debate: “Has Science Refuted Religion?”

Sean Carroll & Michael Shermer v. Dinesh D’Souza & Ian Hutchinson

Beckman Auditorium

Sunday, March 25, 2012 at 2 pm - Born Believers: The Science of Children’s Religious Belief

with Dr. Justin Barrett

Sunday, April 15, 2012 at 2 pm - Subliminal: How Your Unconscious Mind Rules Your Behavior

with Dr. Leonard Mlodinow

Sunday, April 29, 2012 at 2 pm - Consciousness: Confessions of a Romantic Reductionist

with Dr. Christof Koch

Sunday, May 13, 2012 at 2 pm - The Secrets of Mental Math: The Mathemagician’s Guide

to Lightning Calculation and Amazing Math Tricks

with Dr. Art Benjamin

Sunday, June 10, 2012 at 2 pm

NEW ON MICHAELSHERMER.COM

In the Year 9595

We have all heard about Watson, the computer that beat the two best champions on Jeopardy. But, how close are we to having computers emulate human though, become self-aware and take over the world? In this, the January Skeptic column for Scientific American, Michael Shermer ponders the question of artificial intelligence.

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

More God Less Crime, or More Guns Less Crime

During the last week of 2011, Michael Shermer spoke at and attended a salon in Santa Fe, New Mexico at which two of the speakers addressed the topic of the decline of crime, one (Byron Johnson) attributing it to god and the other (John Lott) to guns. In this week’s Skepticblog, Michael Shermer reports on their findings…

Christopher Hitchens on:

“Does Science Make Belief in God Obsolete?”

That was the Templeton Foundation’s Big Question in the third of a series of questions posed to leading scientist and scholars, among them: Steven Pinker, Victor Stenger, Mary Midgley, William D. Phillips, Christoph Cardinal Schönborn and Michael Shermer. In this week’s eSkeptic, we present Christopher Hitchens’ answer. Christopher Hitchens is the author of God Is Not Great. Hitchens died on December 15, 2011 at the age of 62. In tribute to Hitchens, we present this article which was edited by Michael Shermer for the Templeton Foundation’s Big Question Series. Tune in next week for a debate between Hitchens and Kenneth Miller (also part of the Big Questions Series).

No, But it Should

by Christopher Hitchens

Does science make belief in god obsolete? No, but it should. Until about 1832, when it first seems to have become established as a noun and a concept, the term “scientist” had no really independent meaning. “Science” meant “knowledge” in much the same way as “physic” meant medicine, and those who conducted experiments or organized field expeditions or managed laboratories were known as “natural philosophers.” To these gentlemen (for they were mainly gentlemen) the belief in a divine presence or inspiration was often merely assumed to be a part of the natural order, in rather the same way as it was assumed—or actually insisted upon—that a teacher at Cambridge University swear an oath to be an ordained Christian minister. For Sir Isaac Newton—an enthusiastic alchemist, a despiser of the doctrine of the Trinity and a fanatical anti-Papist—the main clues to the cosmos were to be found in Scripture. Joseph Priestley, discoverer of oxygen, was a devout Unitarian as well as a believer in the phlogiston theory. Alfred Russel Wallace, to whom we owe much of what we know about biogeography and natural selection, delighted in nothing more than a session of ectoplasmic or spiritual communion with the departed.

And thus it could be argued—though if I were a believer in god I would not myself attempt to argue it—that a commitment to science by no means contradicts a belief in the supernatural. The best known statement of this opinion in our own time comes from the late Stephen Jay Gould, who tactfully proposed that the worlds of science and religion commanded “non-overlapping magisteria.” How true is this on a second look, or even on a first glance? Would we have adopted monotheism in the first place if we had known:

- That our species is at most 200,000 years old, and very nearly joined the 98.9 percent of all other species on our planet by becoming extinct, in Africa, 60,000 years ago, when our numbers seemingly fell below 2,000 before we embarked on our true “exodus” from the savannah?

- That the universe, originally discovered by Edwin Hubble to be expanding away from itself in a flash of red light, is now known to be expanding away from itself even more rapidly, so that soon even the evidence of the original “big bang” will be unobservable?

- That the Andromeda galaxy is on a direct collision course with our own, the ominous but beautiful premonition of which can already be seen with a naked eye in the night sky?

These are very recent examples, post-Darwinian and post-Einsteinian, and they make pathetic nonsense of any idea that our presence on this planet, let alone in this of so many billion galaxies, is part of a plan. Which design, or designer, made so sure that absolutely nothing (see above) will come out of our fragile current “something”? What plan, or planner, determined that millions of humans would die without even a grave-marker, for our first 200,000 years of struggling and desperate existence, and that there would only then at last be a “revelation” to save us, about 3,000 years ago, but disclosed only to gaping peasants in remote and violent and illiterate areas of the Middle East?

To say that there is little “scientific” evidence for the last proposition is to invite a laugh. There is no evidence for it, period. And if by some strenuous and improbable revelation there was to be any evidence, it would only argue that the creator or designer of all things was either (a) very laborious, roundabout, tinkering and incompetent and/or (b) extremely capricious and callous, and even cruel. It will not do to say, in reply to this, that the lord moves in mysterious ways. Those who dare to claim to be his understudies and votaries and interpreters must either accept the cruelty and the chaos or disown it: they cannot pick and choose between the warmly benign and the frigidly indifferent. Nor can the religious claim to be in possession of secret sources of information that are denied to the rest of us. That claim was, once, the prerogative of the Pope and the witch-doctor, but now it’s gone. This is as much as to say that reason and logic reject god, which (without being conclusive) would be a fairly close approach to a scientific rebuttal. It would also be quite near to saying something that lies just outside the scope of this essay, which is that morality shudders at the idea of god, as well.

Religion, remember, is theism not deism. Faith cannot rest itself on the argument that there might or might not be a prime mover. Faith must believe in answered prayers, divinely-ordained morality, heavenly warrant for circumcision, the occurrence of miracles or what you will. Physics and chemistry and biology and palaeontology and archaeology have, at a minimum, given us explanations for what used to be mysterious, and furnished us with hypotheses that are at least as good as, or very much better than, the ones offered by any believers in other and inexplicable dimensions.

Does this mean that the inexplicable or superstitious has become “obsolete”? I myself would wish to say no, if only because I believe that the human capacity for wonder neither will nor should be destroyed or superseded. But the original problem with religion is that it is our first, and our worst, attempt at explanation. It is how we came up with answers before we had any evidence. It belongs to the terrified childhood of our species, before we knew about germs or could account for earthquakes. It belongs to our childhood, too, in the less charming sense of demanding a tyrannical authority: a protective parent who demands compulsory love even as he exacts a tithe of fear. This unalterable and eternal despot is the origin of totalitarianism, and represents the first cringing human attempt to refer all difficult questions to the smoking and forbidding altar of a Big Brother. This of course is why one desires that science and humanism would make faith obsolete, even as one sadly realizes that as long as we remain insecure primates we shall remain very fearful of breaking the chain. ![]()

Skeptical perspective on faith and spirituality…

-

Atheism: The Case Against God

Atheism: The Case Against God

by George Smith

-

The Soul of Science

The Soul of Science

by Michael Shermer -

Can we find spiritual meaning and purpose in a scientific worldview? Yes! There are many sources of spirituality; religion may be the most common, but it is by no means the only. Anything that generates a sense of awe may be a source of spirituality. Science does this in spades. READ more and order the book.

-

Living Without Religion

Living Without Religion

by Paul Kurtz -

One of America’s foremost expositors of humanist philosophy, Paul Kurtz shows how we can live the good life filled with morality, commitment, and dedication, without having to depend on the existence of a higher being. Drawing upon the disciplines of the sciences, philosophy, and ethics, Kurtz also offers concrete recommendations for the development of the humanism of the future. READ more and order the book.

OUR ANNUAL FUNDRAISING DRIVE IS ON NOW

We need your support!

- Click here to read our new plan to take Skepticism to the next level!

- Click here to make a donation now via our online store.

Monthly Recurring Donation Options Now Available

We encourage you to choose the monthly recurring donation option. Simply tell us how long you want your donation to recur (using the drop-down menu on the donation page) and we’ll set up automatic withdrawal for the amount you select.

Just for considering a donation, check out our free PDF download

created by Junior Skeptic Editor Daniel Loxton.

11-12-28

In this week’s eSkeptic:

OUR ANNUAL FUNDRAISING DRIVE IS ON NOW

We need your support!

- Click here to read our new plan to take Skepticism to the next level!

- Click here to make a donation now via our online store.

Just for considering a donation, check out our free PDF download

created by Junior Skeptic Editor Daniel Loxton.

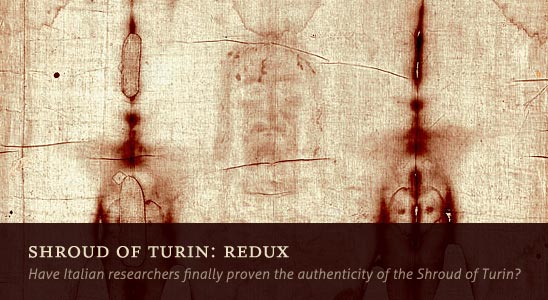

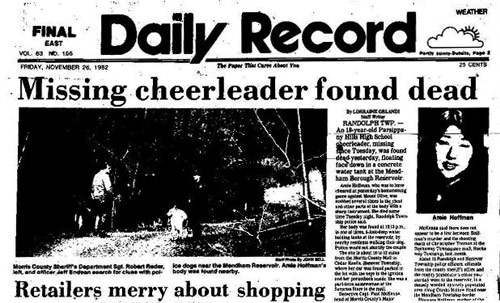

About this week’s eSkeptic

Recently, global headlines have resurrected the decades-old case of the Shroud of Turin in response to a group of Italian researchers who have studied its authenticity and claim that the image it bears (ostensibly of Jesus) was not faked. Though the case for fraud has indeed been strong since the 14th century, skeptics know all too well that some topics just never seem to get laid to rest. In this week’s eSkeptic, Daniel Loxton responds to the media hype.

Shroud of Turin: Redux

by Daniel Loxton

Skeptics sometimes express impatience with discussion of seemingly quaint paranormal claims. (“What, Bigfoot—again?”) But the great lesson of paranormal history is that it is a wheel: no matter how passé or fringe a claim may sound, it is almost guaranteed to come ‘round again, in the same form or in some novel mutation.

In the last few days, global headlines have resurrected a nostalgic case from my childhood, just in time for Christmas: “The Shroud of Turin Wasn’t Faked, Italian Experts Say.” The cutting edge of yesterday—today! Even in my youth, this mystery was centuries old.

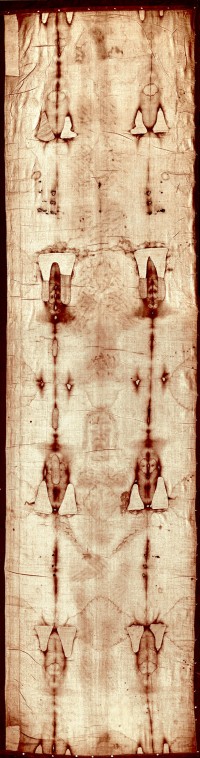

The Shroud of Turin is a 14-foot length of linen cloth that bears a stylized picture of a bearded man. Legend holds the Shroud to be a burial cloth wrapped around the Biblical Jesus following his execution. This linen was allegedly flash-imprinted with an image of Jesus during his miraculous resurrection, presumably by an intense burst of energy released under such circumstances.

The case for fraud has been strong since the 14th century, but enthusiasts insist on rolling that wheel ‘round again. According to news reports this week, Italian scientists used an infrared CO2 laser to scorch images onto cloth and ”conducted dozens of hours of tests with X-rays and ultraviolet lights” in an effort to prove that the image could be created by a burst of electromagnetic energy. (Here’s a PDF of their Italian-language report.) What is the wavelength of a resurrection miracle? If there is one, the scientists were unable to discover what it might be. They learned (in ABC News’s paraphrase) that “no laser existed to date that could replicate the singular nature of markings on the shroud.”

Full-length photograph of the Shroud of Turin which is said to have been the cloth placed on Jesus at the time of his burial. (Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.)

All this business with lasers is neither here nor there. I’m reminded of magician James Randi’s line from Flim-Flam! about the pseudoscience technique of the Provocative Fact.

The same technique was used by the Gellerites when they assured us that at no time did Uri Geller use laser beams, magnets, or chemicals to bend spoons. This was quite true. It is also quite true that he had no eggbeaters, asbestos insulation, or powdered aspirin in his pockets either. So what?1

Turns out it’s hard to make a Shroud copy using lasers. That’s hardly surprising, but neither is it relevant. There was never a good reason to think the Shroud was created by anything but the tools and artistry of a painter. Failed attempts to replicate the Shroud image using lasers only underline the argument skeptics have made for decades: the object is a medieval fake.

The bottom line on the Shroud remains the same: the Shroud continues to fail several key practical tests, as discussed by skeptical investigator Joe Nickell in his classic work on the subject, Looking for a Miracle:2

- Provenance: there is no sign that this object existed before the 14th century;

- Art history: the Shroud fits into art history as part of a genre of artistic depictions and recreations of burial cloths of Christ;

- Style: the image upon the shroud looks like a manufactured illustration consistent with 14th century religious iconography, not like a real human being;

- Circumstance: a 14th century Catholic bishop determined that the Shroud was a “cunningly painted” fraud—and discovered the artist who confessed to creating it;

- Chemistry: the Shroud contains red ochre and other paint pigments;

- Radiometric dating: carbon-14 dating tests showed in 1988 that the Shroud was likely created between 1260 and 1390 CE. In 2008, the hypothesis that this date was distorted by carbon monoxide contamination was tested—and results of the original tests confirmed.

Overturning the robustly supported conclusion that the Shroud was manufactured by a medieval artist would take extraordinary levels of evidence in favor of some alternate explanation. The current media hype carries no such breakthrough news. The opposite is true, in fact: the Italian researchers concede (as quoted by Vatican Insider) that their “inability to repeat (and therefore falsify) the image on the Shroud makes it impossible to formulate a reliable hypothesis on how the impression was made.”

After decades of controversy, the real shame is not merely the miasma of pseudoscience surrounding the relic (that’s a fog skeptics are happy enough to cut through) but the blurring of the lines between science and metaphysics—or if you like, between science and faith. The Shroud’s popularity seems to stem from the hope that it could deliver tangible evidence for the divine, but that hope is misplaced. Even if Shroud researchers were to prove their (exceptionally unlikely) speculation that the Shroud image was imprinted by “a short and intense burst of VUV directional radiation,” this would in no way confirm the existence of God, only of a unique printing process—a process enthusiasts have thus far been unable to demonstrate. The truth is that the tools and methods of empirical science would remain powerless to confirm the existence of a transcendent metaphysical God even in the event that such a being existed. It’s just not the sort of question science can answer.

Pressing science into the service of metaphysics may do harm to religion—I’ll leave it to the religious to say if that is so—but it cuts out the heart of the scientific enterprise. And that is a Christmas present that none of us should want.![]()

References

- Randi, James. Flim-Flam! (Prometheus Books: Amherst, New York, 1982.) p. 129

- Nickell, Joe. Looking for a Miracle. (Prometheus Books: Amherst, New York, 1998.) pp. 22–29

Skeptical must-haves for your library…

-

Flim Flam! Psychics, ESP, Unicorns

Flim Flam! Psychics, ESP, Unicorns

and other Delusions

by James Randi

-

The Skeptic’s Dictionary

The Skeptic’s Dictionary

by Robert Carroll

-

Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time

Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time

by Michael Shermer -

In this age of supposed scientific enlightenment, many people still believe in mind reading, past-life regression theory, New Age hokum, and alien abduction. A no-holds-barred assault on popular superstitions and prejudices, Why People Believe Weird Things debunks these nonsensical claims and explores the very human reasons people find otherworldly phenomena, conspiracy theories, and cults so appealing… READ more and order the book.

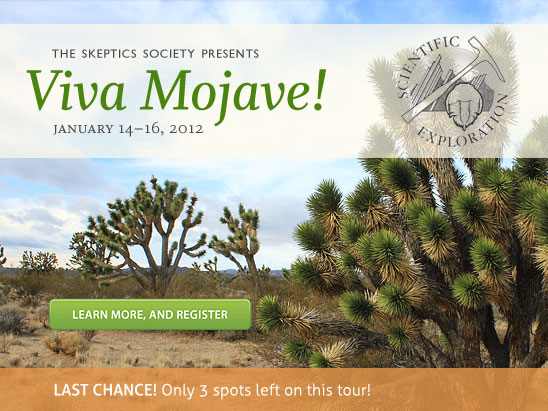

Viva Mojave!

Only 3 spots left for Viva Mojave!

JOIN THE SKEPTICS SOCIETY FOR A WONDERFUL THREE-DAY TOUR of the highlights of the Mojave Desert and the Las Vegas area. We will stop at the historic restored ghost town of Calico and take several tours, visit Afton Gorge where Ice Age floods drained Lake Manix, collect 550 million year old trilobites, experience the spectacular boulders of Red Rock Canyon, and conclude with a guided tour of Hoover Dam.

Click an image to enlarge it.

What’s Included?

Tour price includes charter bus, all hotel accommodations, breakfast and lunch each day, guided tour narration and guidebook, all other admission fees, and a tax-deductible contribution to the Skeptics Society of $130. Seats are limited to about 50 people on a single tour bus, so the tour should fill up fast.

Questions?

Email us or call 1-626-794-3119 with a credit card to secure your spot.

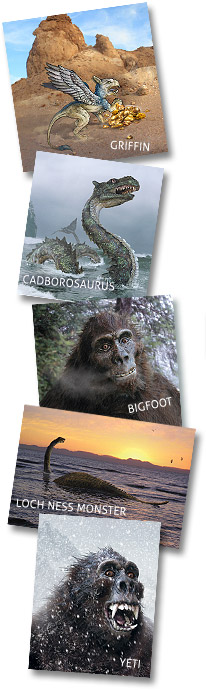

5 Free Junior Skeptic Cryptid Cards

Download and print 5 Cryptid Cards created by Junior Skeptic Editor Daniel Loxton. Creatures include: The Yeti, Griffin, Sasquatch/Bigfoot, Loch Ness Monster, and the Cadborosaurus. CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

TAGS: cryptozoology, free download11-12-21

It is Time Again to Support

Your Skeptics Society!

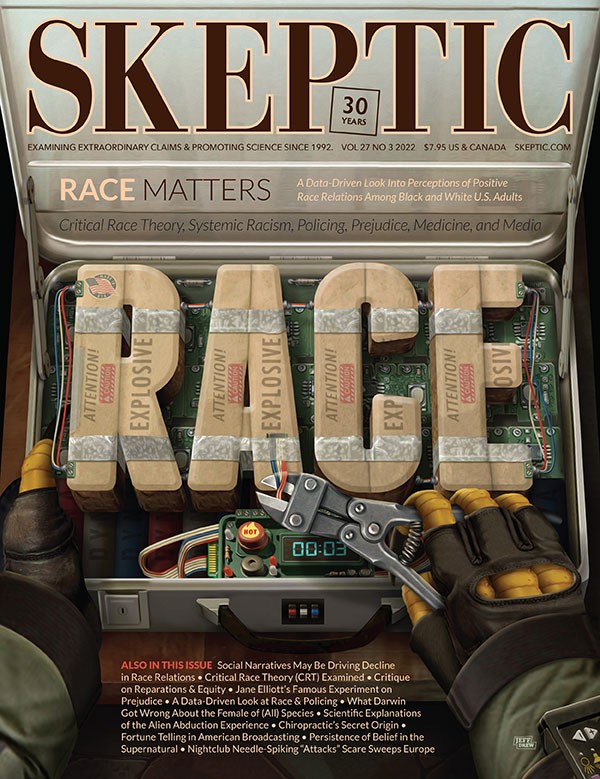

THE SKEPTICS SOCIETY is a non-profit, member-supported 501(c)(3) organization whose goal is to promote skeptical thinking (i.e. thinking like a scientist). Your generous support helps us continue our educational outreach through venues such as:

- Our international quarterly magazine SKEPTIC

(including Junior Skeptic inside every issue) - Our website, podcasts, Facebook, and Twitter

- Our Distinguished Lecture Series at Caltech

- Media interviews on national TV, radio, and in national paper

(opinion editorials, commentaries, and reviews) - University and college lectures

- Michael Shermer’s monthly column in Scientific American

- Skepticblog (with top skeptical writing talent), and

- Our free, weekly email newsletter, eSkeptic.

We’re Taking Skepticism into the Classroom!

This fall semester (2011) Michael Shermer has been teaching a course for Freshmen at Chapman University entitled “Skepticism 101: How to Think like a Scientist (Without Being a Geek).” Students are instructed to write a 700-word OpEd essay, deliver an 18-minute TED talk, and conduct an experiment testing a paranormal claim. They are reading many classic skeptical books and each week Shermer lectures on a classic skeptical topic such as: science and pseudoscience • science and religion • science and morality • evolution and creationism • the Baloney Detection Kit • how science works • Big Foot and Loch Ness, aliens and UFOs, Bermuda Triangle and Atlantis, etc.

Your Donations Will Help Put Skepticism into Schools & Teach Students How to Think, Not Just What to Think

Shermer’s “Skepticism 101” course is a pilot course for the development of a Skeptical Studies Curriculum that can be used in any classroom anywhere in the world, from middle school to high schools, and community colleges to universities. We are building a free, comprehensive online resource center dedicated to Skeptical Studies that will allow anyone, anywhere, anytime, to access for free any and all materials they might need to teach such a class of their own design, including:

- Syllabi, reading lists, articles

- Essays, lectures and notes, PowerPoint/Keynote presentations

- Videos, YouTube links, educational and entertaining in-class demonstrations on how to teach skeptical principles and the psychology behind them with hands-on experiences

- Other teaching tools that visually illustrate key points of skeptical thinking on how science works and how thinking goes wrong.

We have already begun collecting hundreds of submissions from teachers around the world as result of our initial invitation to submit skeptical course syllabi. With your help we can put Skepticism 101 resources on the web—a free, easy access location for educators wanting to introduce a particular topic to a class or to develop an entire course. To that end please take a moment to donate and support this worthy project.

Free Cryptid Cards (for considering a donation)

As our thank you to you for your generous support, we are offering a free download of 5 Cryptid Cards created by Junior Skeptic Editor Daniel Loxton. Loxton won the prestigious Lane Anderson Award for the best Canadian science book of the year for young readers: Evolution: How We and All Living Things Came to Be, a work that generated enormous media coverage, including the fact that the book was rejected by American publishers for being too controversial because it deals with the “E” word! As the Globe and Mail noted:

Daniel Loxton, an illustrator and writer, created a children’s book so outrageous, so outlandish, so controversial no American publisher dared touch it. It does not depict nudity. It does not contain curse words. It does not include blasphemy. The love scenes, such as they are, involve males with females. It does include a straightforward explanation for the complexity of the natural world through a simple scientific theory. The book wound up being published by Canadian-owned Kids Can Press, which also expected objections from creationists. So far, the book, an illustrated primer written for readers in Grades 3 to 7, has generated more prize nominations than controversy.

For contributions that fit a donation amount below,

you are eligible to receive the associated gift(s).

- PATRON—$5000 or more

- A private dinner with our Executive Director Michael Shermer at a restaurant of your choice, plus the three premium gifts listed below.

- BENEFACTOR—$1,000 or more

- Five of the “Greatest Hits” lectures from our Caltech lecture series on DVD: Mr. Deity & Friends, Michio Kaku’s The Physics of the Future, Sean Carroll’s From Particles to People, Leonard Mlodinow’s The Grand Design, and Sam Harris’ The Moral Landscape, plus the two premium gifts below.

- SPONSOR—$500 or more

- A copy of Jared Diamond’s latest book, Natural Experiments of History, plus Daniel Loxton’s new book, Ankylosaur Attack, for kids aged 4 to 7 with stunningly realistic images of dinosaurs and deceptively simple but information- packed scientifically accurate story, plus the premium gift below.

- SUPPORTER—$100 or more

- An autographed copy of Michael Shermer’s new book, The Believing Brain: From Ghosts and Gods to Politics and Conspiracies: How We Construct Beliefs and Reinforce Them as Truths.

What We Did With Your Donations This Past Year

- Michael Shermer’s new book, The Believing Brain, made it to the New York Times bestseller list thanks to the national book tour (that included an appearance on the Colbert Report). On tour, Shermer met with local skeptics groups in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, Denver, San Francisco, Berkeley, Los Angeles, Washington DC, and New York.

- The Skeptics Society hosted a Science Symposium at Caltech with over 700 people in attendance, including hundreds of high school and college students from all over the United States, and even from around the world.

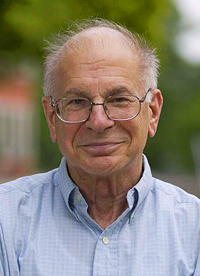

- The Skeptics Society’s Distinguished Science Lecture Series at Caltech featured Fields Medal winner Shing-Tung Yau, cosmologist Sean Carroll, astronomer David Weintraub, string theorist Michio Kaku, neuroscientist Patricia Churchland, biologist Tim Flannery, geologist Don Prothero, twins expert Nancy Segal, theoretical physicist Lisa Randall, psychologist Steven Pinker, Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman, evolutionary theorist Robert Trivers, neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga.

- The Skeptics Society hosted three geology tours featuring Donald Prothero, including a remarkable cruise through the inside passage of Alaska for spectacular glacier viewing. We have more geology tours planned for 2012.

Questions?

If you would like to speak with someone directly, please contact our donations coordinator by email at donations@skeptic.com or by phone at 1-626-794-3119.

My Dinner (and Drinks) with Christopher

(Hitchens that is)

An essay tribute by Michael Shermer, written upon hearing of Hitchens’ cancer diagnosis in 2010. This post first appeared at Skepticblog.org (July 20, 2010) and is syndicated here today, on the occasion of Hitchens’ death: December 15, 2011.

The conjunction of reading Christopher Hitchens’ new memoir, Hitch 22, and the news of his treatment for esophageal cancer, reminded me that I should share my (admittedly limited) experiences of dining (and drinking) with one of the greatest literary masters and creative thinkers of our age.

First, I’m half way through listening to the unabridged audio book of Hitch 22, which I wholeheartedly recommend because Christopher reads it himself in that inimitable classically-educated British accent with his style of flowing quiet narrative punctuated with occasional bursts of accented emphasis. In other words, Hitchens sort of mumbles modestly along, then suddenly his voice rises into crystal clarity when he wants you to get the point hard and fast. Hitch 22 is a literary masterpiece, an absolute joy to listen to. I’ll leave it to his literary/politico peers to critique the ideas within (see, for example, the latest issue of CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

TAGS: Christopher Hitchens, tribute11-12-14

In this week’s eSkeptic:

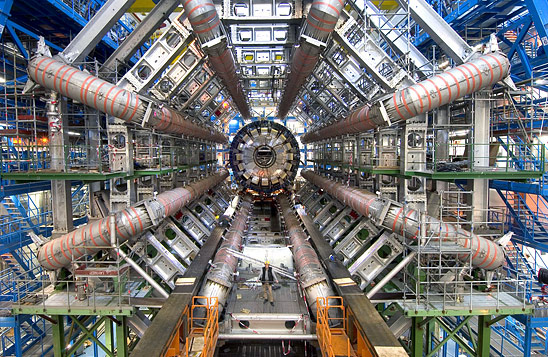

Interview with Scott Hannahs

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 172

This week’s guest on Skepticality is Dr. Scott Hannahs, the Director of DC Field Instrumentation and Facilities National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. Find out a bit about what it is like to work with the worlds most powerful magnet, what types of experiments require such a powerful bit of scientific equipment, and what discoveries and research come out of the science of magnetic fields.

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, Michael Shermer reviews Margaret Wertheim’s Physics on the Fringe: Smoke Rings, Circlons, and Alternative Theories of Everything. This book review first appeared in the Wall Street Journal on December 10, 2011.

On the Margins of Science

book review by Michael Shermer

As the editor of Skeptic magazine and a monthly columnist for Scientific American I am often sent self-published books and manuscripts that I store in a box labeled “Theories of Everything.” These are mostly attempts at constructing all-encompassing explanatory theories claiming to have disproven Newton, Einstein, and Hawking, and that in 10 or 100 pages sans equations or references the secrets of the cosmos are revealed. One is entitled “Introduction to the Unified Field Theory,” in which the author boasts, “I have discovered the previously unknown invisible particle that fully explains light and all forms of energy. I call it the froton particle. Einstein didn’t know about the froton particle—but you will.” A manuscript entitled Infinite Dynamics goes “beyond Einstein,” and represents “an historic, classical, artistic, scientific, philosophical paradigm shift.” Another called Photonics promises “Einstein’s unified-field theory now complete, all forces finally unified,” and as a bonus, “fundamental cause of gravity found.” Another proclaimed that his “is the first consistent theory of anti-gravity in the history of mankind,” revealing the secrets to “time warp interstellar travel, wormhole engineering and Dipole Antigravity Drive, gravitational free energy, and alien visitation.”

I admit that I have not given these ideas much credence, but what if one of them turns out to be right, or at least has something of value to offer to society? For the past 15 years the acclaimed science writer Margaret Wertheim (Pythagoras’ Trousers, The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace) has been collecting the works of such hermit scientists, or what she calls “outsider physicists,” and with the patience of Job has undertaken the scientifically thankless task of carefully reading as many “theories of everything” as she could get her hands on to give them a fair hearing, and more. In Physics on the Fringe Wertheim presents these ideas with an eye toward challenging our preconceptions of what science is, how it works, and who it is for. The book is so well-written, entertaining, and enlightening that I read it straight through in one sunny day at the beach. Only later did I realize that Wertheim has also taken on one of the knottiest conundrums in the philosophy of science called the demarcation problem, or finding criteria to define the boundary between science and pseudoscience. It’s not as easy as it sounds.

As a professional debunker I feel like I know bunk when I see it, and Wertheim has well captured the genre: “In all likelihood there will be an abundant use of CAPITAL LETTERS and exclamation points!!! Important sections will be underlined or bolded, or circled, for emphasis. Frequently the author will have seen fit to ease the professor’s path toward understanding by writing helpful comments in the margins of the paper or by highlighting critical passages with brightly colored felt-tip pens… The text itself will almost certainly herald its revolutionary nature in its opening paragraphs, claiming to reinvent if not the whole of physics…then at least substantial parts of it. At a minimum, the author will be proposing something radically new and often as not will have harsh words for the twin pillars of twentieth-century physics—relativity and quantum theory.”

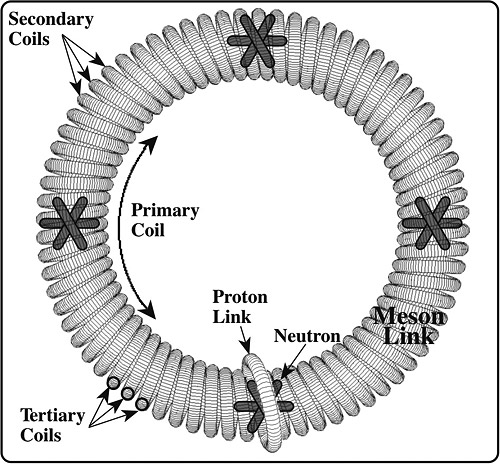

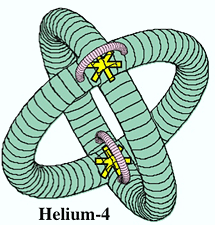

Outward appearances aside, Wertheim has convinced me that I may be too hasty in dismissing outsiders a priori, most notably the central character of her story—a man she calls the Einstein of outsiders, Jim Carter, who has developed his own complete theory of matter, energy, and gravity that he demonstrates by experiments in his backyard with DIY contraptions involving garbage cans and a disco fog machine, from which he makes smoke rings to test his ideas about atoms, which he believes are constructed of “circlons,” or “Hollow, ring-shaped mechanical particles that are held together within the nucleus by their physical shapes,” as seen in Figure 1 (below), and in representing the helium atom in Figure 2, the 2nd simplest element made up of two circlons. His circlon theory allows him to tie together both quantum mechanics and the special and general theories of relativity, and his explanation for gravity is unorthodox to say the least: “if the earth’s surface is constantly moving away from its center, we must conclude that the earth, as well as all other matter, is constantly expanding in size; and it is this expansion that causes the phenomenon we know as gravity.”

Figure 1: The Circlon (courtesy of Jim Carter). See also Jim Carter’s Circlon Model of Nulcear Structure (PDF, copyright 1993).

Figure 2: The Helium Atom Circlon (courtesy of Jim Carter). See the Physics on the Fringe website for more information about Jim Carter’s physics, including links to photos and videos.

Before you laugh (especially at the neologism), as I initially did, Wertheim points out that string theory—touted regularly on science documentaries as the ultimate theory of everything endorsed by prominent scientists the world over—has not a shred of empirical evidence in its favor and is, in reality, nothing more than a mathematically elegant construct. If Carter’s circlon theory is pseudoscience, why isn’t string theory? For example, Wertheim describes a meeting she attended of the Natural Philosophy Alliance, a group devoted to challenging mainstream physics. The eccentric event played host to no fewer than 121 fringe theories of the universe, “each claiming to present a key to Ultimate Reality,” Wertheim recalled. It reminded her of the book The Three Christs of Ypsilanti, the story of three schizophrenic patients in a room together at the Ypsilanti State Hospital in Michigan, all of whom thought they were Jesus (each of whom ultimatey decided that the other two were imposters). At this conference, she recounted, “Everybody had the Answer. Everybody was the One.” There was bewilderment amongst the participants: “How exactly is a person supposed to respond to someone else’s harebrained theory when each person has his or her own Solution?”

Wertheim goes on to contrast the NPA gathering with a meeting of string theorists she attended in which such scientific supernovae as Stephen Hawking, Lisa Randall and Brian Greene spoke seriously about 11-dimensional universes, multiverses, parallel universes, and even the possibility of there being at least 10500 variants of string cosmologies, including one proffered by Stanford’s Leonard Susskind in which every universe that can exist does exist in a superuniversal space. When Wertheim asked the organizer of the insiders conference his opinion of one particularly dazzling talk, he enthused “Utterly splendid. Of course there’s not a shred of evidence for anything the fellow said.” As Wertheim recalled, “Whoever I talked with assured me that everybody else’s theories were unsupported by evidence and based entirely on arbitrary assumptions. None of this was driven by physical discoveries.”

What, then, are we to do with outsiders’ contributions to science? When they are contrasted with equally baseless theories, says Wertheim, listen to them. “In the final analysis Jim’s circlon-shaped particles may also be seen as manifestations of a string theory, for his subatomic springs are also coils of some minutely thin, ‘stuff.’ Jim came to the string concept more than thirty years ago, and the fact that this idea is now being embraced by the mainstream suggests to him that his other ideas will one day be vindicated too.”

Will they? Maybe. Or perhaps both circlon theory and string theory will go the way of phlogiston and phrenology on the scrapheap of science history. Time and observation will tell, for as the great astrophysicist who confirmed Einstein’s theory of relativity, Arthur Stanley Eddington, noted: “For the truth of the conclusions of science, observation is the supreme court of appeal.” In the meantime, let’s not dismiss outsiders before giving them their day in court. Margaret Wertheim has done just that in this splendid book.

May we suggest these related items…

-

Heaven and the Internet

Heaven and the Internet

by Margaret Wertheim

-

Who is Science Writing For?

Who is Science Writing For?

by Margaret Wertheim

-

Skeptic magazine volume 10, no. 2

Skeptic magazine volume 10, no. 2

includes a special report on Stephen Wolfram by David Naiditch -

In 2002, the legendary Stephen Wolfram stepped into the public eye promising to revolutionize the way we do science. For hundreds of years, scientists have successfully used mathematical equations that show how various entities are related. Wolfram believes that simple computational rules (rather than equations) could better capture the complexities of nature. According to Wolfram, the discovery that simple rules can generate complexity—a discovery he attributes primarily to himself—is “one of the more important single discoveries in the whole history of theoretical science.”

READ the Table of Contents and order the back issue.

Physics on the Fringe: Smoke Rings, Circlons,

and Alternative Theories of Everything

and Alternative Theories of Everything

FOR THE PAST 15 YEARS acclaimed science writer Margaret Wertheim has been collecting the works of “outsider physicists,” many without formal training and all convinced they have found true alternative theories of the universe. Jim Carter, the Einstein of outsiders, has developed his own complete theory of matter and energy and gravity that he demonstrates by experiments in his backyard—with garbage cans and a disco fog machine, he makes smoke rings to test his ideas about atoms. Captivated by the imaginative power of his theories and his resolutely DIY attitude, Wertheim has been following Carter’s progress for the past decade. Through a profoundly human profile of Carter, Wertheim’s exploration of the bizarre world of fringe physics challenges our conception of what science is, how it works, and who it is for.

TAGS: fringe physics, Jim Carter11-12-07

In this week’s eSkeptic:

Lecture Sunday: Margaret Wertheim

Physics on the Fringe: Smoke Rings, Circlons,

and Alternative Theories of Everything

Sunday, December 11, 2011 at 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

FOR THE PAST 15 YEARS acclaimed science writer Margaret Wertheim has been collecting the works of “outsider physicists,” many without formal training and all convinced they have found true alternative theories of the universe. Jim Carter, the Einstein of outsiders, has developed his own complete theory of matter and energy and gravity that he demonstrates by experiments in his backyard—with garbage cans and a disco fog machine, he makes smoke rings to test his ideas about atoms. Captivated by the imaginative power of his theories and his resolutely DIY attitude, Wertheim has been following Carter’s progress for the past decade. Through a profoundly human profile of Carter, Wertheim’s exploration of the bizarre world of fringe physics challenges our conception of what science is, how it works, and who it is for.

Tickets are first come, first served at the door. Seating is limited. $8 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $10 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

NEW ON MICHAELSHERMER.COM

Sacred Salubriousness

In the December Skeptic column for Scientific American, Michael Shermer looks at new research on the link between religion, behaviour, goal achievement and self-control.

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

Paleolithic Politics

Research in cognitive psychology shows, for example, that once we commit to a belief we employ the confirmation bias, in which we look for and find confirming evidence in support of it and ignore or rationalize away any disconfirming evidence. In this Skepticblog, in light of the group-psychology of our ancestral past, Michael Shermer looks at how the confirmation bias affects our still-tribal political process.

Unbottling some Jinn

If you think Genies are funny like in Aladdin, or sexy like in I Dream of Jeannie get ready to have your assumptions challenged. In the Middle East, Jinn aren’t whimsical characters of fantasy. They are considered to be frightening, real entities that haunt desolate places and can perform terrible magic. In this episode of MonsterTalk we interview author Robert Lebling about his book Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar. If you miss this episode you’ll wish you hadn’t!

Get the Podcast App

for your Android phone.

(iPhone App coming soon)

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, we present Karen Stollznow’s “Bad Language” column from Skeptic magazine volume 16, number 4 (2011) in which she looks at some of the pseudoscientific claims about the healing powers of sounds. Though most sound healing claims are just a lot of hot air, could there be some legitimate applications of sound technology being used to heal?

Healing and Harming Sounds

by Karen Stollznow

Illustration by Nancy White

Pavarotti singing Nessun Dorma from Puccini’s Turandot can bring people to tears, but can the tenor’s voice heal too? Can sounds both cure and kill? Let’s investigate some claims about healing and harming sounds.

Many people seem to think there’s something magical about human speech; for example, the belief that uttering spells and prayers can bring about an effect in the external world. Some practitioners even claim to be able to cure disease using the human voice. As usual, there are many names for the claims: Bioacoustics, Sound Therapy, Sound Work and Sound Medicine. All of these methods purport to harness the alleged healing power of our own voices.

One proponent, Paul Newham, believes that good health requires not only a sensible diet and exercise, but also singing. His book The Singing Cure teaches “Voice Movement Therapy,” a series of exercises based on “vocal healing traditions” from indigenous cultures.1 Newham claims the voice is a powerful healing instrument that can be used to tame anger, grief, shame and other negative emotions.

One “certified therapist” in Voice Healing conducts sessions of singing to reduce stress, ease pain and create a “cellular level of healing”:

This powerful healing technique which dates back to ancient civilizations and new scientific researches, will enable you to use the power of your voice vibration to improve your health and life. This course is for everybody; the human voice is a very powerful tool. it was not only created to speaking or singing, but also to heal and help each one of us (having a beautiful voice is not relevant) to achieve a state of greater self awareness. Once we get to know our voices with the help of intensive training we will be able to cure ourselves from many disturbing diseases and multiple pains caused by stress, such as insomnia, migraine, abdominal pain, heart problems, sinusitis, cold flu, and more…2

The Discovery Channel television series Mythbusters proved that with the right frequency and volume, and when sustained, it is possible to shatter glass with the human voice.3 However, no note is going to cure the common cold. Like mantras and meditation, singing only has subjective benefits for the individual.

Another therapist uses the voice in conjunction with music, drums, quartz crystal bowls and tuning forks, to return our voices to their “healthy state of resonance”:

We arrive on this planet with every thing that we need to heal ourselves, and when we came; our voices were rich with all the necessary frequencies to maintain us in a healthy state of resonance. Due to the conditioning of childhood and the suppression of our true thoughts and feelings and the accompanying sounds that go with them, by the time we arrive at adulthood our speaking voice no longer contains the same frequencies it did as a child. Our voice will always reflect our current mental and emotional states of being. When a person feels alive, healthy, happy and abundant, their voice sounds much different than if they are depressed, unhappy, angry or afraid. You may notice a difference in your own voice when speaking your truth compared to when you are not, it feels different in your body as well, and from an energetic standpoint the cells of your body are not getting the frequencies they need to stay healthy.4

Consistent with the beliefs of other holistic therapies such as naturopathy, this therapist claims that we all have a natural healthy state to which we can return using the body’s innate ability to heal itself.

To return to this inherent state of health, Alfred A. Tomatis experimented with the most seminal of sounds—a mother’s voice. To his patients, Tomatis played recordings of their mother’s voices to treat a variety of disorders, including dyslexia, autism and depression. He also used Gregorian chants and music by composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. To this day, proponents of the Tomatis Method claim his listening techniques treat learning difficulties, and assist in learning second languages, developing better communication skills and improving creativity.5

By now, the idea of using Mozart music might be sounding familiar. Don Campbell took Tomatis’ research further with his book The Mozart Effect: Tapping the Power of Music to Heal the Body, Strengthen the Mind, and Unlock the Creative Spirit. Campbell believes that listening to Mozart music boosts intelligence, and in The Mozart Effect for Children he claims that exposing children to classical music increases brain development.

Campbell’s theory was popularized before it could be (dis)proven. The mere claim led then Governor of Georgia, Zell Miller, to propose issuing the parents of newborn children with a CD of classical music.6 In an effort to produce more milk, a dairy farmer in Spain plays Mozart during milking time, in what is affectionately known as the Moozart Effect.7

However, research does not support the claim that listening to Mozart can enhance spatial performance.8 Furthermore, there is no evidence to support Campbell’s additional claims that his therapy treats a range of conditions including autism, dyslexia and Attention- Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).9 Much like the “we only use 10% of our brains” myth, the belief that “listening to Mozart makes you smarter” has outlived its debunking.

Again, any benefits of listening to classical music are based in perception, like taste in music. One person’s Mozart is another person’s Metallica. Similarly, there is no music that will literally “expand your mind” like the claims of Squareeater that their psychedelic music “stimulates the brain to lead users to the furtherest edges of the conscious mind.”10

Music isn’t always used to soothe the savage beast; sometimes it’s used as a torture tactic. There was a curious soundtrack to the 1993 Waco siege of David Koresh and his disciples. When negotiations failed, the Federal Bureau of Investigation surrounded the Branch Davidian ranch and blasted high-decibel music into the compound to subdue the occupants. The bizarre playlist included Tibetan chants, Christmas carols, bugle calls and Nancy Sinatra’s These Boots Are Made for Walkin’. Like Charles Manson, Koresh fancied himself a rock star, and retaliated by playing tapes of his own compositions, until the electricity was cut off….

U.S. soldiers unleashed this rock ‘n’ roll warfare during the 1989 invasion of Panama. A cacophony of Styx, Judas Priest, Black Sabbath, and a version of God Bless the U.S.A. was blasted into the papal nunciature—Manuel Noriega’s hiding place—until the Vatican put an end to the concert. Closer to home, classical music is pumped into the PA systems of some shopping malls in an attempt to lower crime and deter teenagers from loitering (because Beethoven isn’t cool).

Sometimes earplugs aren’t enough. Sonic weapons are coming out of science fiction and into use for defense and law enforcement. Instruments such as Long Range Acoustic Devices (LRAD) are used as hailing devices and in crowd control efforts. An LRAD was even used to ward off a group of pirates off the coast of Somalia. High-power sound waves can be used to incapacitate a victim, and can cause disorientation, discomfort and nausea.

The very technology used to harm may be used to heal. Researchers at the California Institute of Technology have created “sound bullets” that could eventually be used to obliterate kidney stones or destroy cancerous cells without damage to surrounding tissue.11 The device is based on the old toy Newton’s Cradle, and creates concentrated sound waves from ball bearings.

In experimental research, sound waves are being used to treat prostate cancer. In a study conducted at the University College Hospital and Princess Grace Hospital in London, High Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) is used to kill cancerous cells. The results are promising; the cancer was treated successfully, with fewer side effects than chemotherapy.12

As we can see, there are some legitimate applications for sound technology, but there are many pseudoscientific theories about speech and sound. The claims that singing can cure disease and listening to music can make you smarter are just a load of hot air.![]()

References

- Paul Newham. 1993. The Singing Cure: Introduction to Voice Movement Therapy. Rider & Co.

- Manifesting Mind Power. Voice Healing. www.manifestingmindpower.com/voice%20healing.htm Accessed 04/20/2011.

- Karen Schrock. 2007. “Fact or Fiction? An Opera Singer’s Piercing Voice Can Shatter Glass.” Scientific American.

- The Healing Voice. www.soundtransformations.com/sacredvoice.htm Accessed 05/12/2011.

- Tomatis Method. www.tomatis.com Accessed 05/11/2011.

- Kevin Sack. 1998. “Georgia’s Governor Seeks Musical Start for Babies.” The New York Times. www.nytimes.com/1998/01/15/us/georgia-s-governor-seeks-musical-start-for-babies.html Accessed 05/11/2011.

- Rebecca Lee. 2007. The Moozart Effect. abcnews.go.com/Technology/story?id=3213324&page=1#.Tt6l5WCt_8g Accessed 05/11/2011.

- Pippa McKelvie, Jason Low. 2010. “Listening to Mozart does not improve children’s spatial ability: Final curtains for the Mozart effect.” Developmental Psychology. Vol. 20, No. 2, 241–258.

- Campbell, Don. 1997. The Mozart Effect: Tapping the Power of Music to Heal the Body, Strengthen the Mind, and Unlock the Creative Spirit. Quill Publishing.

- Squareeater. www.squareeater.com/ Accessed 05/17/2011.

- “Sound bullets” could blast cancer. ABC Science. April 2010. www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2010/04/06/2865165.htm Accessed 04/20/2011.

- Ahmed et al. 2009. “High-Intensity-Focused Ultrasound in the Treatment of Primary Prostate Cancer: The First UK series.” 1 July. British Journal of Cancer.

Suggested reading on sound perception, faith healing, and prayer…

-

Phantom Words & Auditory Illusions

Phantom Words & Auditory Illusions

by Dr. Diana Deutsch

-

The Faith Healers

The Faith Healers

by James Randi

-

Blind Faith: The Unholy Alliance

Blind Faith: The Unholy Alliance

of Religion & Medicine

by Richard Sloan -

Is there a scientific connection between prayer and healing? A majority of Americans believe there is, but by taking a hard look at the scientific evidence, Columbia University Professor of Behavioral Medicine, Richard Sloan, believes there is no proven curative power to prayer and that the use of it as a medical treatment undermines effective patient care. Sloan exposes the questionable research practices and unfounded claims made by scientists who manipulate scientific data and research results to support their claim of effective mystical intervention in healing. READ more and order the hardback book.

11-11-30

In this week’s eSkeptic:

The Latest Episode of Mr. Deity: Mr. Deity and the Bang

WATCH THIS EPISODE | DONATE | NEWSLETTER | FACEBOOK | MrDeity.com

Upcoming Lecture: Margaret Wertheim

Physics on the Fringe: Smoke Rings, Circlons,

and Alternative Theories of Everything

Sunday, December 11, 2011 at 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

FOR THE PAST 15 YEARS acclaimed science writer Margaret Wertheim has been collecting the works of “outsider physicists,” many without formal training and all convinced they have found true alternative theories of the universe. Jim Carter, the Einstein of outsiders, has developed his own complete theory of matter and energy and gravity that he demonstrates by experiments in his backyard—with garbage cans and a disco fog machine, he makes smoke rings to test his ideas about atoms. Captivated by the imaginative power of his theories and his resolutely DIY attitude, Wertheim has been following Carter’s progress for the past decade. Through a profoundly human profile of Carter, Wertheim’s exploration of the bizarre world of fringe physics challenges our conception of what science is, how it works, and who it is for.

Tickets are first come, first served at the door. Seating is limited. $8 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $10 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

Is America a Christian Nation?

Readers Respond To Chuck Colson

In a recent Los Angeles Times Op-Ed about Congress reaffirming the US national motto “In God We Trust,” Michael Shermer argued that trust does not come from God but from very specific social, political, and economic institutions. Chuck Colson argued that “God Has a Lot to Do With It.” In this week’s Skepticblog, readers respond to Colson.

MonsterTalk meets Skeptiko: The Psychic Detective Finale

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 170

In September of 2008, Ben Radford appeared as a guest on the podcast Skeptiko, hosted by Alex Tsakiris. During that interview, he agreed to take up Alex’s challenge to investigate the best case of the efficacy of psychic detectives. What followed was months of research, numerous interviews and a follow-up which ended in acrimony. Now, three years after the initial challenge, Skepticality presents a discussion between the hosts of MonsterTalk (Blake Smith, Ben Radford and Karen Stollznow) and Alex Tsakiris about Skeptiko, the interface of skeptics and believers, and the matter of whether or not Ben’s investigation disproved the psychic’s claims.

Interview with Joseph Lazio

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 171

In this episode of Skepticality, Derek speaks with Joseph Lazio, project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory for the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) telescope. Learn about what this next-generation radio telescope will be searching for and discover how it will address some of the fundamental questions in astrophysics, physics, and even astrobiology.

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, Michael Shermer reviews Lisa Randall’s Knocking on Heaven’s Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern World (Ecco, 2011), a book in which Randall attempts “the herculean task of explaining to us uninitiated the daunting science of theoretical particle physics.” This review was originally published in the November 2011 issue of Science magazine.

As Far As Her Eyes Can See

book review by Michael Shermer